Bavarian Zugspitzbahn

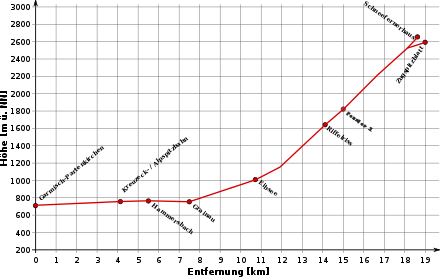

| Garmisch – Zugspitzplatt / Schneefernerhaus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Route number (DB) : | 9540 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Course book section (DB) : | 11031 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route length: | 19.5 km | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gauge : | 1000 mm ( meter gauge ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Power system : | 1650 volts = | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum slope : |

Adhesion 35.1 ‰ rack 250 ‰ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rack system : | System Riggenbach | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Top speed: | 70 km / h | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 47 ° 29 '30.4 " N , 11 ° 5' 49.3" E

The Bayerische Zugspitzbahn is next to the Wendelsteinbahn , the Drachenfelsbahn and the rack railway Stuttgart one of four still operated rack railways in Germany (see also: List of rack railways # Germany ).

The meter-gauge route leads from the Garmisch-Partenkirchner district of Garmisch to the Zugspitze , the highest mountain in Germany. It is operated by Bayerische Zugspitzbahn Bergbahn AG (BZB) , a subsidiary of the Garmisch-Partenkirchen municipal works. In 2007 the Zugspitzbahn was nominated for the award as a " Historic Landmark of Civil Engineering in Germany ".

The Zugspitze summit can alternatively be reached with the Zugspitze cable car or the Tyrolean Zugspitzbahn .

Route

The Zugspitzbahn begins in the Garmisch district at an altitude of 705 m above sea level. NN as an adhesion railway in a completely operationally separate station from the neighboring standard gauge station of Deutsche Bahn AG . For the first three kilometers it runs parallel to the Ausserfernbahn , which has existed since 1913 , and then crosses the state railway in a rising curve with a sheet metal girder bridge. The route then ends in the Katzenstein tunnel and leads from there to the Kreuzeckbahn and Alpspitzbahn cable cars . From there, the route is straight and gently sloping to the Grainau district of Hammersbach. It bypasses the foot of the Waxensteine and crosses the village of Grainau. At Grainau station, the adhesion section ends after 7.5 kilometers with the start of the mountain section. There is also the operational center of the railway with the car hall. Past the wagon hall, the route continues to the Christlhütte and from there parallel to Eibseestrasse, with gradients of up to 150 ‰. Following the station Eibsee the route leads up to 250 ‰ by the slope Zugwald and traverses a short tunnel a Mure . Immediately after the tunnel, the railway leads in a tight curve over a 12 meter high embankment. After the Riffelriß stop, the route ends in the 4.5 kilometer long Zugspitze tunnel . The tunnel section leads in several loops upwards towards the Zugspitzplatt. At the junction in the tunnel, the route divides into the old tunnel to the Schneefernerhaus on the one hand and the new Rosi tunnel to the Sonnalpin on the other. Both stations are designed as underground terminal stations. The rack section was originally 11.1 kilometers long and, with the opening of the new tunnel to the Sonnalpin, was extended to 11.5 kilometers, the route totaling 19.0 kilometers.

history

Prehistory and construction

Since the end of the 19th century there were ideas to open up the Zugspitze with a train. Different concepts of funicular railways , cable cars and cog railways were considered, but all of them failed due to a lack of a license or a lack of money.

Still rejected by the Bavarian Ministry of Commerce in 1924 , a consortium of Allgemeine Lokalbahn- und Kraftwerke AG in Berlin, AEG Berlin and Treuhandgesellschaft AG in Munich was granted a building and operating permit for a mixed adhesion and cog railway on April 1, 1928 . In the course of the detailed planning, some points were changed compared to the original planning. The end point of the cable car was not created at the summit, but 350 meters below the Zugspitzplatt, which was then connected to the summit by a cable car. Likewise, the track width was increased from the original 750 mm to 1000 mm and instead of the multiple units with mixed adhesion and gear drive of the first draft, locomotive-hauled trains were used.

The railway was built in three sections between 1928 and 1930:

Due to the difficult land acquisition in the Garmisch-Eibsee section, construction could not begin there until the summer of 1929. The overpass structure of the Zugspitzbahn over the Ausserfernbahn, which consists of a sheet metal girder bridge with two 17.3 meter spans and a bridge ramp, should be mentioned as engineering structures. The excavated material from the directly adjoining Katzenstein tunnel was used to fill the ramp. Furthermore, near the Kreuzeckbahn stop, there is an overpass of the Kreuzeckbahnstraße with a 9.9 meter span in reinforced concrete construction. Another underpass was built between Grainau and Eibsee at the level of the car hall.

In the section between Eibsee and Riffelriß, work could already begin in the summer of 1928. There, on the one hand, the steep slope of the terrain caused difficulties during construction, and on the other hand, the short tunnel at kilometer 13.0, as it was led through a mudslide that had not yet settled. A 12 meter high dam was built next to the tunnel.

The greatest difficulty of the entire route was the construction of the 4.2 kilometer long Zugspitze tunnel in the third section between Riffelriss and Schneeferner. For this purpose, the entire mountain range was measured in summer 1928 and several auxiliary cable cars were built from autumn 1928. The tunnel advance could thus be started from five points at the same time and completed on February 8, 1930 with the breakthrough to the Schneeerner.

First, on February 19, 1929, the 3.2 km long middle section between Grainau and the Eibsee went into operation. On December 19, 1929, the 7.5-kilometer section between Garmisch and Grainau followed, which also established the important tourist connection to the Deutsche Reichsbahn . Now abandoned - - Summit Station on July 8 In 1930, the last 7.9 kilometers between the Eibsee and were Schneefernerhaus solemnly released.

Further development

In 1987 the route in the summit area was modified, at that time the 975 meter long “Rosi Tunnel” was opened. It is named after the tunnel godmother , the skier Rosi Mittermaier . The tube branches off in the upper quarter of the Zugspitze Tunnel, which has been in existence since 1930, and leads to the slightly lower Zugspitzplatt at 2588 meters. The new glacier train station is located there under the “Sonn-Alpin” restaurant in the middle of the ski area. Both endpoints were served in parallel for five years, but since November 1992 the old route to the Schneefernerhaus has no longer been used as scheduled.

In 1987 and 1988 the valley section was also renovated and made for speeds of up to 70 km / h. Since then, the double multiple units that were purchased at the time have been able to reach their maximum speed. The track systems of Garmisch train station were dismantled and the Kreuzeckbahn and Hammersbach train stations were turned back into stops. Until then, there was still a loading siding for goods in the Garmisch station southeast of the passenger station, to which a standard-gauge siding led from the Garmisch-Partenkirchen station. The Rießersee stop was completely abandoned.

The superstructure of the mountain route has been renewed since 1996. The Riggenbach ladder rack system previously installed is being replaced by the compatible Von Roll lamellar rack system .

After the accident in the Katzenstein tunnel, the entire route was equipped with signals , train control and an electronic interlocking from the company BBR Verkehrstechnik from Braunschweig.

A covered central platform was built in Grainau in 2000 to make it easier to change between the valley and mountain ranges. The Eibsee train station has also been fundamentally modernized, with a roofed central platform and an extension of the reception building.

The Zugspitze tunnel was equipped with fire protection gates to prevent a chimney effect in the event of a fire .

Accidents

The accident in the Katzenstein tunnel occurred on June 10, 2000, and was the worst accident in the history of the Bavarian Zugspitzbahn.

Picture gallery

View from the Riffelriß demand stop immediately before entering the summit tunnel

vehicles

The following vehicles are or were available to the Bayerische Zugspitzbahn as operating resources.

| image | Company number | design type | Installation | Manufacturer | comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 to 4 | Bo | 1929 | AEG | No. 1 and 4 in operation, 2 and 3 as a monument |

|

11 to 18 | 1zzz1 | 1929 | AEG | No. 14 and 15 in operation, 11 as a memorial |

|

19th | 1zz1'1zz1 ' | 2017 | Stadler Rail | |

|

1 to 4 | 1zz1'1zz1 ' | 1954-1958 | MAN, AEG, SLM | all retired |

|

5 and 6 | 1zz1'1zz1 ' | 1978 | SLM, BBC | |

|

10 and 11 | 1Az'1Az '+ 1Az'1Az' | 1987 | SLM, Siemens | |

|

12 to 16 | Bozz'Bozz'Bozz ' | 2006 | Stadler Rail | |

|

309 | Bozz'Bozz ' | 1979 | SIG, SLM, BBC | With BZB since 1999, renovation by Stadler Rail |

The railcars 5, 6, 10, 11, 12 to 16 and 309 and the mountain locomotive 19 are in regular use. In addition to the locomotives, the BZB also operates passenger, freight and work cars .

Technical features

Right from the start, all vehicles were equipped with an automatic central buffer coupling of the Scharfenberg type. The only exception to this is the railcar 309 with its two control cars 211 and 213, which have retained their original + GF + coupling.

Furthermore, the first generation of vehicles was equipped with automatic Hardy type vacuum brakes . In order to be able to transport the passenger and freight cars with the newer vehicles, they were also equipped with vacuum equipment. Again an exception are the railcar 309 and the control car 211/213, which are only equipped with air brakes.

The mountain locomotives 11 to 18 and the railcars 1 to 6 are equipped with ice scrapers, which clean the overhead line of snow and ice. With the ice scrapers, contact problems of the pantograph when there is ice on the overhead line and thus the formation of arcs are suppressed.

As is usual with electric rack and pinion railways, the Zugspitzbahn also uses electric brakes to brake when going downhill, as these are able to keep the speed constant without wear. With an electric regenerative brake , electricity is fed back into the overhead line, which in turn can be used by trains traveling upwards. This means that electricity can be saved in total. However, since the Zugspitzbahn usually has very jerky traffic (in the morning, many passengers go uphill and in the afternoon they all go downhill again), there is no compensation between the trains going downhill and downhill. In the early years of the railway, electrical feedback into the national network was also out of the question due to the expensive converter technology . For this reason, resistance brakes were installed in all older vehicles , in which the electrical energy is converted into heat in braking resistors. The drag brake works independently of the mains, i.e. H. the brake still works if the contact line voltage fails, which in turn would lead to the failure of the brake in the case of an electrical regenerative brake. Since the power supply system is now equipped with converter technology, the newer generations of traction vehicles have electrical regenerative brakes. This means that excess energy can be fed back into the national grid when going downhill. However, in order to be able to guarantee a safe descent in the event of a failure of the contact line voltage, the newer traction vehicles are also equipped with a braking resistor. This means that the new locomotives can also be driven into the valley with the pantographs lowered during thunderstorms. This is common practice on the Zugspitzbahn to reduce the risk of a lightning strike. In addition, maintenance work can be carried out on the overhead line that has been de-energized with a mountain locomotive traveling downhill and the tower car.

business

The valley section was operated in train control until the signaling system was commissioned . For this purpose, the Garmisch, Kreuzeckbahn and Hammersbach stations were equipped with fallback switches until they were dismantled . This enabled train crossings and the relocation of the locomotives to change the direction of travel without local staff in the stations.

A special feature of the Zugspitzbahn is the so-called follow - up train operation when there is a particularly high rush. Up to three parts of the train share a route by following each other within sight . All three parts of the train run under the same train number , but each receive a letter for internal differentiation. The last part in the direction of travel is given the letter A, the next in front the letter B and again the next part the letter C. The last part of the train is marked with specially illuminated signal discs on which the black A can be seen on a white background. This shows that the last part of the train has arrived in a siding. Only when the last of the three train parts has crossed , the train traveling in the opposite direction is allowed to leave the siding. In the early years, the train that arrived first in the siding set the points for the second train by hand. Later the turnouts were equipped with a push button control, similar to an electrically localized turnout . Today, the two remaining turnouts 3 and 4, like all other stations, can be operated centrally by means of an interlocking and are equipped with signals. The switches and the platforms were built for train lengths of around 60 meters. In follow-up train operations, this corresponds to a train in two train parts, each consisting of a mountain locomotive plus two passenger cars or a railcar plus a presentation car. Since two double railcars in multiple units are also around 60 meters long, subsequent train operations are now limited to journeys that are not carried out with the double railcars.

passenger traffic

When operations opened in 1930, four valley locomotives, eight mountain locomotives and 18 passenger cars were delivered. A valley locomotive brought up to six, with a leader up to seven, passenger cars to Grainau, where the mountain locomotives took over the transport. A mountain locomotive was allowed to carry three passenger cars below the Eibsee station, which is why the trains on the valley route, if they were longer than three cars, were divided into Grainau. Above the Eibsee station, only two passenger cars were allowed to be carried by the mountain locomotives, the third was parked in the Eibsee station. With the locomotive-hauled trains, passengers could cover the entire route without having to change trains.

In the second half of the 1950s, with the commissioning of the first railcars, the travel time on the mountain route was significantly reduced. The railcars displaced the mountain locomotives more and more from passenger transport. This reduced the throughput of passenger cars to individual wagons that were placed in front of the railcars in Grainau by the valley trains. The other passengers had to change trains in Grainau. In the summer of 1958, the timetable was changed to hourly intervals to further improve the offer. The two circuits required for this between Grainau and Schneefernerhaus could, if required, also be operated with two railcars each in subsequent train operations. Additional trains on the mountain route during peak load times and all traffic on the valley route continued to be driven by locomotive-hauled trains.

In 1978, with the commissioning of railcars 6 and 7, the scheduled passage of passenger cars from Garmisch to the Zugspitze ended, and the mountain locomotives were replaced from the regular passenger service. So now all passengers had to change in Grainau.

When the two double railcars 10 and 11 went into operation in 1987, the route could have been crossed again without having to change trains, but since two double railcars are not sufficient for the entire operation, they were mainly used on the valley route between Garmisch and Grainau. When there was a heavy rush of passengers, the two double railcars commuted between Garmisch and Eibsee and railcars 1 to 6 between Eibsee and Zugspitze. The double railcars displaced the valley locomotives from the regular passenger train service, which resulted in a reduction in travel times on the valley route. Since then it has been possible to offer every half hour on the valley route.

From 2002, the passenger train service on the valley route was largely taken over by the 309 railcar with the 211/213 control cars. Together with the two double railcars 10 and 11, the three required rotations could be made in off-peak times . When the number of passengers rushed, railcars 1 to 6 were also used.

With the commissioning of the new double multiple units 12 to 16 in autumn 2006, the multiple units 1 to 4 were taken out of service. The double railcars 10 to 16 drive through with low to normal crowds from Garmisch to Zugspitzplatt without changing trains. The three circuits required for this can also be driven in double traction with two coupled railcars each . However, if there is a large number of passengers, traffic in Grainau will continue to be split. Then the 309 railcar with the 211/213 control car commutes on the valley route and the double railcars in double traction between Grainau and Zugspitze.

In order to be able to offer a continuous half-hourly service between Eibsee and Zugspitze during the construction phase of the new Zugspitz cable car in 2017, a total of five circuits were required. That is why the new mountain locomotive 19 with two passenger cars and / or the multiple units 5/6 were used as the fifth set during peak load times.

Freight transport

Until the opening of the Eibsee cable car in 1963, the rack railway was the only way to transport drinking and service water, fuels, building materials and supplies from the German side to the Zugspitze, and to transport waste back into the valley.

For the water supply, a water filling station was set up on the mountain route at kilometer 11.9 between Eibsee and siding 3. Here, water was collected and transported up to the Schneeernerhaus or the Sonnalpin by means of water tanks on freight cars. Since 1996 the water supply has been guaranteed via a high pressure water pipe through the tunnel to the Sonnalpin station.

Until the siding to Garmisch-Partenkirchen station was closed, goods could be handled there by standard-gauge freight wagons. Today, food, building materials and other supplies are loaded from the truck onto the train at the Grainau depot. Track material for the mountain route is often loaded in the Eibsee station.

In addition, the cog railway is the only way to transport machines and technical equipment for the ski area. Thus, groomers , equipment and components for lifts using the freight cars on the Zugspitzplatt transported. To transport the snow groomers, the caterpillar chains, the front shield and the rear tiller must be removed.

The freight wagons are occasionally carried by the mountain locomotives or by the railcars as presentation wagons.

Tariff

As one of the few non-federally owned railways (NE), the Bayerische Zugspitzbahn is not integrated into the so-called NE kick-off tariff . In exchange traffic between the Deutsche Bahn AG and the Bayerische Zugspitzbahn, no through tickets can be purchased in accordance with the nationwide valid transport conditions of Deutsche Bahn AG . However, the Bayern ticket is valid in the Garmisch – Grainau section . In addition, passengers traveling with Deutsche Bahn AG are given discounts on the price of the ascent and descent. On the valley portion Bayerische Zugspitzbahn guarantees it within the public transport system , a basic service to the population. In this area, the company's in-house tariff, which is not integrated into the local Garmisch-Partenkirchen transport association , provides significantly lower tariffs than for the mountain route that is exclusively relevant to tourism. In 2016, for example, a trip from Garmisch to Grainau cost EUR 2.90, while the total distance, which is slightly more than twice as long, was EUR 31.50. In addition, there is free transport for the severely disabled in the valley section and weekly and monthly tickets are offered for frequent travelers.

In 2016, the Bayerische Eisenbahngesellschaft intended to award the local rail passenger transport of the Garmisch - Grainau valley route to the Bayerische Zugspitzbahn in a direct procedure by 2031, as the Zugspitzbahn is the only company that owns suitable vehicles. The performance on the route is around 40,000 train kilometers per year.

Former station names

Some stations of the Bavarian Zugspitzbahn changed their names over time. They used to be called as follows:

- Garmisch: Garmisch-Partenkirchen BZB

- Hausberg: Hausbergbahn

- Rießersee: Rießersee BZB

- Kreuzeck- / Alpspitzbahn: Kreuzeckbahn valley station

- Hammersbach: Hammersbach (Höllental)

- Grainau: Grainau ( Badersee )

- Schneeernerhaus: Hotel Schneefernerhaus

Power supply

Since the power supply of the Zugspitzbahn could not be ensured by the local power generators, Isarwerke GmbH set up two 43 kilovolt lines to the newly built Degernau substation in 1928 . One line came from the direction of Murnau, where there was a connection to a line from the Mühltal hydropower station ; the other from the Krün substation, with a connection to Bayernwerke . A three-phase current line runs from the Degernau substation , first as an overhead line , then on the masts of the overhead line to the substation on Lake Eibsee.

The overhead line was initially fed exclusively via the substation on the Eibsee. There, three-phase current was converted into direct current with 1650 volts by means of a mercury vapor rectifier . The rectifiers were arranged in three vector groups with 750 kVA each, two groups being sufficient for normal operation. Depending on the load on the power supply system, the voltage can fluctuate by up to 300 volts.

In 1977 the Eibsee substation was equipped with diode rectifiers with an output of two times 1250 kVA. With the commissioning of railcars 5 and 6, a further substation was built on the platform of the originally planned Höllental stop , which originally had an output of 630 kVA. As part of the construction work, the voltage of the supply line was also increased from 8.5 to ten kilovolts.

When the valley section was rebuilt in the mid-1980s, another substation was built at km 3.6. This Tal substation has an output of 1600 kVA and is required for the operation of the more powerful double railcars. In 2002 the Höllental substation was expanded to a capacity of 1600 kVA. The supply voltage was further increased to 20 kilovolts.

With the commissioning of the double multiple units 12 to 16, a further substation with a capacity of two times 1600 kVA was built at the Riffelriß station. This substation received an inverter in addition to the rectifiers. With this system it is possible that the electricity fed back by the appropriately equipped vehicles can be converted back into three-phase current and fed back into the national grid.

Depot

The six-permanent wagon hall with the maintenance workshop is connected to the Grainau train station . All maintenance and repair work on the vehicles is carried out there. Four of the stands are equipped with racks and all six with examination pits. A stand in the wagon hall was equipped with a 30 meter long lifting platform, which is able to lift a double multiple unit for maintenance work. The seventh gate on the left side of the depot leads to the paint shop. A track is arranged on the left and right of the wagon hall for loading work and parking. The entrance to the wagon hall is designed as a track harp.

literature

- Paul Schultze-Naumburg : Zugspitzbahn . In: Rudolf Pechel (Ed.): Deutsche Rundschau . November 1926, ZDB ID 2644744-7 .

- Otto Behrens: With the suspension railway to the Zugspitze . In: Reclam's Universe: Modern Illustrated Weekly . tape 42.2 , 1926, pp. 1091-1092 (three illustrations).

- Erich von Willmann: The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung . tape 50.1930.11 . Ernst, March 19, 1930, ZDB -ID 2406062-8 , p. 223–225 ( opus.kobv.de [PDF; 2.8 MB ] five figures).

- The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: AEG (Ed.): Messages . Issue 4, April 1931, ISSN 0374-2423 .

- Josef Doposcheg: Zugspitze and Zugspitzbahn. History and natural history guide . Adam, Garmisch 1934.

- Erich Preuß: The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn and its cable cars . Transpress, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-613-71054-4 .

- Gerd Wolff: German small and private railways . 7: Bavaria. EK-Verlag, Freiburg 2002, ISBN 3-88255-666-8 .

Web links

- Bavarian Zugspitzbahn Bergbahn AG

- Photos of the Zugspitzbahn by Wolfgang Mletzko

- Early documents and newspaper articles on the Bavarian Zugspitzbahn in the 20th Century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- New route to the Zugspitze: Rediscovered Steig Documentation of a historical climb through the north face that was rediscovered using photos, films and relics, over which workers reached the caverns and tunnel windows, and which was now continued to the summit. By Georg Bayerle, broadcast on Bayerischer Rundfunk.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Railway Atlas Germany . 9th edition. Schweers + Wall, Aachen 2014, ISBN 978-3-89494-145-1 .

- ↑ Information and pictures about the tunnels on route 9540 on eisenbahn-tunnelportale.de by Lothar Brill

- ↑ a b The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: AEG (Ed.): Messages . Issue 4, April 1931, ISSN 0374-2423 , construction of the Garmisch – Schneefernerhaus line, p. 218-232 .

- ↑ Little Chronicle. (...) No train to the Zugspitze. In: Neue Freie Presse , Morgenblatt, No. 21325/1924, January 23, 1924, p. 8, bottom center. (Online at ANNO ). .

- ↑ The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: AEG (Ed.): Messages . Issue 4, April 1931, ISSN 0374-2423 .

- ↑ The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: AEG (Ed.): Messages . Issue 4, April 1931, ISSN 0374-2423 , construction work, p. 220-232 .

- ↑ Daily news. (...) Opening of the Bavarian Zugspitzbahn. In: Wiener Zeitung , No. 156/1930, July 9, 1930, p. 5 middle. (Online at ANNO ). .

- ↑ a b c d e Erich Preuß: The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . transpress, 1997, ISBN 3-613-71054-4 .

- ^ Siegfried Bufe: Rack railways in Bavaria. Munich 1977, p. 80.

- ↑ The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: AEG (Ed.): Messages . Issue 4, April 1931, ISSN 0374-2423 , Lokomotiven, p. 250-261 .

- ^ Rainer Weber, Anton Zimmerman: The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn and its new vehicles . In: Eisenbahn Revue International . No. 10/2007 . MINIREX AG, October 2007, ISSN 1421-2811 , p. 510-515 .

- ↑ Michael Burger: Electric mountain locomotive 19 of the Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: Eisenbahn-Revue International . No. 12 . MINIREX AG, December 2017, ISSN 1421-2811 , p. 601-607 .

- ↑ a b c d The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: AEG (Ed.): Messages . Issue 4, April 1931, ISSN 0374-2423 , Betrieb, p. 288-292 .

- ↑ Gerd Wolf: German small and private railways . tape 7 . EK-Verlag, 2002, ISBN 3-88255-666-8 , Bayerische Zugspitzbahn AG (BZB), p. 185-208 .

- ↑ Bayern ticket. Bavarian Railway Company, accessed on June 12, 2016 .

- ↑ öpnv-info. Retrieved February 22, 2019 .

- ↑ Prices Zugspitze cog railway valley route - summer winter 2015/2016. (PDF) In: zugspitze.de. Retrieved June 12, 2016 .

- ↑ Bavaria: Zugspitzbahn should continue to run. In: eurailpress.de. July 14, 2016, accessed December 12, 2017 .

- ^ Ostler, Josef: Garmisch and Partenkirchen: 1870-1935: the Olympic site is created . In: Association for history, art and cultural history in the district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen eV (Hrsg.): Contributions to the history of the district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen . tape 8 . Association for history, art and cultural history in the district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Garmisch-Partenkirchen 2000, ISBN 3-9803980-0-5 .

- ↑ The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: AEG (Ed.): Messages . Issue 4, April 1931, ISSN 0374-2423 , power supply, p. 233-247 .

- ↑ a b c Greif Tomas, Schid Wolfgang, Schomburg Alexander, Weber Rainer: Energy efficiency by inverter in dc traction power supply at Bayerische Zugspitzbahn . In: Electric Railways . Issue 3 (107), 2009.

- ↑ a b milestones. (PDF) (No longer available online.) In: zugspitze.de. March 2, 2012, archived from the original on March 2, 2012 ; accessed on December 21, 2017 .

- ↑ Defects in new railcars almost eliminated. In: merkur.de. BZB, March 19, 2007, accessed on March 14, 2018 .

- ↑ The Bavarian Zugspitzbahn . In: AEG (Ed.): Messages . Issue 4, April 1931, ISSN 0374-2423 , Hochbauten , p. 265-281 .

Remarks

- ↑ a b Other sources speak of 1500 volts

- ↑ One of these concepts was e.g. B. that of the engineer WA Müller from 1907, see Anonymus: General project of the Zugspitzbahn. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 322, 1907, pp. 388-392.