Costanza e fortezza

| Opera dates | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Costanza e fortezza |

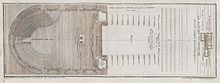

View of the stage of the theater |

|

| Shape: | Festa teatrale in three acts |

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | Johann Joseph Fux , Nicola Matteis |

| Libretto : | Pietro Pariati |

| Premiere: | August 28, 1723 |

| Place of premiere: | Prague, Prague Castle , amphitheater |

| Playing time: | approx. 5 ½ hours |

| Place and time of the action: | near Rome, June 9, 508 BC Chr. |

| people | |

|

|

Costanza e fortezza (German: consistency and strength ) is a festa teatrale in three acts by Johann Joseph Fux (music) with a libretto by Pietro Pariati . The music for the ballets and the concluding license comes from Nicola Matteis . The work was on August 28, 1723 on the occasion of the coronation of Emperor Charles VI. about the King of Bohemia in a specially built open-air theater in the courtyard of Prague Castle , the so-called Hradschin .

action

The opera takes place near Rome on June 9, 508 BC. The historical background can be found in the second book of Titus Livius ' Ab urbe condita: The Roman king Lucius Tarquinius Superbus was overthrown and banished from Rome because of his tyrannical regime. To regain their power, the Tarquinians made an alliance with the Etruscan king Porsenna . The fighting eventually led to the siege of Rome by the Etruscans. The actual plot is about the peace negotiations between Rome and the Etruscans, which are complicated by the chaos of love, as well as the exploits of some Romans. Again and again, parallels are drawn between Rome and the Austrian Empire. Even the title of the work is based on Charles VI's personal motto. ("Constantia et Fortitudine"). Empress Elisabeth , whose birthday was celebrated on the day of the premiere, receives special appreciation through her equation with the goddess Vesta. Each of the three acts is concluded by a ballet. At the beginning and at the end of the work there is an elaborate stage transformation.

The Etruscans under their King Porsenna besiege Rome to put Tito Tarquinio, the son of the expelled King Lucio Tarquinio "Superbus", back on the throne. They took some prisoners, including Valeria and Erminio, the children of the Roman consul Publio Valerio . Valeria loves the Roman Muzio , but is also sought after by Porsenna. Tarquinio as well as Erminio are in love with the Roman noble lady Clelia , but she is engaged to Orazio .

At the beginning, the river god of the Tiber promises Rome a great future. Porsenna sends Valeria and Erminio on their word of honor to peace negotiations in Rome. His conditions are the transfer of the throne to Tarquinio and his marriage to Clelia. The negotiations fail and the two hostages return to the Etruscans. Tarquinio then starts an unauthorized attack on Rome, which Orazio fends off by defending the Tiber Bridge on his own, while it is demolished behind him. He then swims back to the Roman bank.

In the second act, Muzio tries to free Valeria from the hands of the Etruscans. Since she wants to stay in order not to disappoint her father, he instead attempts an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Porsenna. He is arrested but proves his "persistence and strength" by putting his hand in the altar fire. Impressed, Porsenna releases him and agrees a truce with Publio Valerio. After a dispute between Clelia's admirers Tarquinio, Erminio and Orazio, Orazio Tarquinio calls for a duel, which Porsenna can prevent.

At the beginning of the third act, Tarquinio tries to rape Clelia. She successfully defends herself and snatches his sword from him. Erminio prevents her from killing her opponent. Clelia then frees the Roman hostages and swims with them over the Tiber to Rome. Tarquinio blames Orazio and has him arrested. Orazio draws his sword indignantly, but lets Muzio appease him that Publio Valerio should decide his fate. He appears for further negotiations and leads the escaped Clelia back to the Etruscan camp. Clelia explains her escape with Tarquinios attempting to rape, which she can prove with his sword. Porsenna drops Tarquinio and agrees to make peace with Rome.

first act

Wide field with the Tiber and the Sublicius Bridge near Rome

On one side the magnificently decorated Temple of Vesta , in the distance various views of Rome. On the other is the country palace of Tarquinios, which has fallen into ruin in many places. Forest and the Gianicolo, occupied by the Etruscan army.

Scene 1. The Etruscans Porsenna, Tarquinio and the soldiers sing about the expected fall of Rome, while Valeria, Erminio and the other Roman prisoners invoke the invincibility of the city (chorus: “Ceda Roma; o spenta cada”).

Scene 2. Suddenly a huge mass of water rises from the river. River nymphs appear and promise Rome security, since today is Vesta's birthday, the patron goddess of Rome (chorus: “Roma, non paventar”).

Scene 3. The water column sinks back and the realm of the Tiber becomes visible. His personification appears with other river gods, and they also assure that Rome will not go under (chorus: "Spera, o Roma"). In its aria, the Tiber calls on the audience to pay homage to the empress as well as Rome to Vesta (Tevere: "L'Ire deponi: e Vesta adora"). The apparitions withdraw.

Scene 4. Porsenna offers Valeria and Erminio to let them return to Rome on their word of honor. They are supposed to persuade their father and the Senate to recognize Tarquinio as king. Since Erminio considers this proposal dishonorable, Tarquinio declares that he wants to marry the Roman woman Clelia and rule with her. Valeria points out that Clelia is loyal to both her fatherland and her fiancé, Orazio. Erminio, who also secretly loves Clelia, takes note of this with concern. Porsenna calls on Tarquinio to deploy his troops. Tarquinio compares their strength with that of the (Etruscan) lion, to whom everything must give way (Tarquinio: "Al magnanimo Leone"). Then he leaves the camp, followed by some of the soldiers. The remaining soldiers approach to guard Valerias and Erminios.

Scene 5. Left alone with his two prisoners, Porsenna declares his love for Valeria and promises to share the Etruscan throne with her if Tarquinio receives that of Rome. When Valeria and Erminio indignantly refuse this request, Tarquinio insists that their father Valerio should make a decision. Valeria promises to make him his offer, but swears to remain loyal to her fiancé Muzio. Porsenna is not deterred by this (Porsenna: "Se regna in su quest 'alma il tuo sembiante"). Valeria and Erminio are led to the Roman camp by the guards.

Scene 6. Valeria and Erminio initially meet Clelia, Muzio and Orazio. The people greeted her with renewed praise for Vesta (choir: “Lodi a Vesta: a Vesta onori”).

Scene 7. While everyone joins the chant, the consul Publio Valerio appears with the lictors . He embraces his children. Erminio points out that they are not yet finally free and that Porsenna is strengthening the siege at this moment. He was only ready for a peace if Publio Valerio surrendered the throne to Tarquinio and sealed it with Clelia's hand. Publio Valerio considers this condition unheard of and accuses his son of having defected to the enemy. His anger intensifies when Valeria reports on Tarquinio's advertisement for her. Muzio also reacts indignantly - he believes she has been unfaithful to him. But since Valeria and Erminio assure that they have turned down all offers, they calm down quickly. Publio Valerio sends Erminio back to Porsenna to inform him of his decision. Erminio obeys - happy to be able to act honorably (Erminio: "Lieto i 'torno a mie catene").

Scene 8. Muzio apologizes to Valeria for his outburst of anger. When Orazio and Clelia and Publio Valerio speak for him, she forgives him. Publio Valerio asks them to return to the Etruscan camp as well. Valeria says goodbye to her lover (Valeria: "Pensa, che fosti, e sei") and leaves with the Etruscan soldiers.

Scene 9. Publio Valerio explains to Muzio and Orazio that he is primarily a Roman and only a subordinate father (Publio Valerio: “Padre son; ma figlio a Roma”). He enters the temple, followed by the nobles and the lictors.

Scene 10. Muzio can't stand knowing Valeria is in the hands of the enemy. He wants to follow her to free her. Clelia and Orazio stop him and persuade him to calm down for the good of the fatherland. Hesitantly, Muzio gives in (Muzio: “Farò, che per un poco”).

Scene 11. Clelia understands Muzio's excitement. When Orazio points out to her that love must take precedence over her duties to Rome, she envies Valeria for her lover's loyalty - she believes that Orazio will not behave so honorably when she finds herself in need. Yet she assures him of her love. Their conversation is interrupted by the sound of trumpets from the Etruscan camp. An attack is imminent. Orazio sends some soldiers to the temple to notify Muzio.

Scene 12. Muzio arrives with the soldiers. From the other side of the river, Tarquinio and the Etruscan troops are approaching. Orazio asks Muzio to take care of Clelia because he wants to face the enemy alone on the Sublicius Bridge. After a short prayer to the Tiber, he assures the terrified Clelia that he is not really alone, because with him are strength, honor, fame and victory (Orazio with chorus: “Non è solo Orazio, no”). While he - cheered on by the Roman soldiers ("De 'Romani la virtù osa tutto: e tutto può") - defends the position against the Etruscans, Muzio lets the bridge tear down at his call.

Scene 13. Publio Valerio comes out of the temple with the Roman knights and the lictors and admires Orazio's bravery. After the Etruscans called off the attack, Orazio throws himself into the river to return to the Roman bank. The Etruscans shoot a few arrows at him and then retreat to the Janiculum. Clelia, who observed what happened, believes he perished (Clelia: "Non mi resta da sperar").

Scene 14. Muzio reports that in the face of Orazio's outstanding deed, the river itself rose to bring it unscathed to the saving bank. The act ends with praise to the goddess Vesta (“Gran Diva possente”).

Ballet of the Salians

In the subsequent ballet of the “Salians” or Mars priests (chorus: “Per te più irato, e nubilo”) the allegory of Roman stability (“Costanza Romana”) fights against the Etruscan value (“Valore degli Etruschi”), disarms it and breaks it its lance.

Second act

Camp of the Etruscan army near Rome; royal quarters with the sumptuous tents of Porsenna and Tarquinio

Scene 1. In the presence of Erminios, his guards, officers and soldiers, Porsenna demands an explanation from Tarquinio as to why he carried out the attack without his permission. Tarquinio replies that he acted out of anger at Clelia's rejection. Porsenna replies that he, for his part, would endure Valeria's rejection and must answer her virtue with virtue. He sends Erminio to his father for further negotiations. Erminio swears to keep the peace (Erminio: "Vaghi al pari di ulivi, e di palme"). Since the bridge was destroyed, he goes to the river bank with some of the soldiers and a captain.

Scene 2. Tarquinio doesn't think further negotiations make sense. Friendliness will only make Publio Valerio more haughty. Porsenna replies that on the contrary, insults would strengthen him. The Roman power ("La Romana Fortezza") has already won a victory today, and Tarquinio should strive more for the empire than for love. In the meantime, their people should make an offering to the gods. The Etruscan soldiers praise their leader (chorus: "Vivi eterno: e vinci semper"). Porsenna enters his tent, followed by Tarquinio and the captain. The guards stay outside. Some soldiers come out with sacks full of money, as does the captain, and behind them other soldiers with various ostentatious objects from Porsenna.

Scene 3. Muzio tries to get Valeria to flee. However, she insists on following her father's will and staying in the enemy camp. She is a bride, but first and foremost a daughter. The two observe the preparations for the Etruscan Festival of Sacrifice. They say goodbye when in doubt as to whether they will see each other again (duet: “Parto: ma forso, o Dio!”). When Valeria turns to the side so as not to have to see the departure of her lover, Muzio quickly and resolutely steps into the royal tent to murder Porsenna.

Scene 4. Valeria worries about Muzio's fate because she cannot live without him.

Scene 5. Instead of Porsenna, Muzio killed one of the guards. To Valeria's horror, he is arrested. Nevertheless, he manages to draw his dagger and point it at the guards. He hurls curses at Porsenna and gives him his name. The Etruscan soldiers furiously demand his death (chorus: “Morte, morte al traditor”). When asked by Porsenna to give the reasons for his attack, Muzio gives a passionate speech in which he assures that other Romans will follow his example and that Porsenna must expect death at any moment. When Porsenna threatens him with torture, Muzio himself puts his hand in the altar fire and lets it burn. Porsenna and Tarquinio are impressed. Valeria rushes to him to bandage his hand with a scrap of her veil. She begs Porsenna for leniency (Valeria: "Salda ho l'alma ne l'amar").

Scene 6. Erminio announces the arrival of Publio Valerio for the negotiations. Tarquinio points out that he will only be appeased if he receives the Roman throne and the hand of Clelia. He enters his tent. The soldiers position themselves in front of their flags.

Scene 7. Trumpets sound and Publio Valerio appears with the lictors and Roman noblemen as well as Orazio and Clelia. First, Muzio's fate is negotiated. Publio Valerio declares that Muzio is guilty of death and hands him over to Porsenna's vengeance. Porsenna has Muzio's sword handed to him, but then pardons him because of his "persistence and strength" and gives him the sword back. The Etruscans praise his generosity (Tutti: "Pari non ha di lui"). Muzio leaves with some of the soldiers.

Scene 8. Porsenna and Publio Valerio agree on an armistice, for the safety of which both parties want to take hostages. Publio Valerio gives Porsenna the choice between Clelia, Valeria and Orazio. Porsenna opts for Valeria (Porsenna: "Parmi già, ch'io vegga amore"). He goes away.

Scene 9. Publio Valerio, Orazio, Erminio and Clelia are impressed by Porsenna's generosity. Publio Valerio believes that those who are shrouded in fame will never behave in a cowardly or dishonorable manner (Publio Valerio: “Prima che mai si abbassi”). He and his subordinates enter Porsenna's tent. The other soldiers withdraw.

Scene 10. Clelia, Orazio, and Erminio wonder why Tarquinio didn't attend the trial. This overhears their conversation. Clelia assures Orazio that she will never marry Tarquinio even as king (Clelia: "Saprei morir"). She wants to leave, but is stopped by Tarquinio.

Scene 11. Tarquinio demands an explanation as to why Clelias is so resolute in rejecting him. There is an argument between him, Clelia, Orazio and Erminio. Tarquinio insults Orazio and Erminio and is challenged by Orazio to a duel.

Scene 12. Porsenna's intervention prevents the worst. Orazio gives in for the time being, but assures Tarquinio that he will not forget the insults (Orazio: "Questo ferro a te nel petto"). He goes away.

Scene 13. Porsenna calls the harus peaks. Everyone is hoping for a happy future (Tutti: “Fausto a noi ci ascolti il fato”).

Ballet of the Tuscan Haruspices

The Haruspizen recognize from the flight of an eagle (the imperial symbol of the good ruler) and a falcon (the bad ruler Tarquinio) that “pride” will never gain the throne (chorus: “Il bel volo di quell'Aquila”). The "love" and the "fame" dance around the haruspices. Shortly afterwards the Roman strength (“Fortezza Romana”) appears, which first dances alone and then together with “love” and “fame” and is finally crowned with laurel by the two. The Haruspizen explain that the virtue of a king does not need vain worship ("incerti fiori"), but has its reward within itself.

Third act

Royal Gardens of the Tarquinians on the Gianicolo; the moon is in the sky

Scene 1. Tarquinio gives his soldiers an encouraging speech. After they have withdrawn, Clelia appears. Tarquinio becomes intrusive and threatens to use violence. Clelia succeeds in snatching his sword from him. She strikes out to kill him with it.

Scene 2. Erminio steps between Clelia and Tarquinio and prevents the murder at the last moment. Clelia explains to him that Tarquinio tried to rape her. She lets him go but keeps his sword. Tarquinio makes a few more threats and then leaves (Tarquinio: "Cambia in fulmine mortale").

Scene 3. Clelia tells Erminio that she is planning an action that will equate her fame with Orazios. She declines his help resolutely (Clelia: “Con la scorta del maggior”).

Scene 4. After Clelia leaves, Erminio reflects on his own unrequited love for her (Erminio: “Per amar con più di fasto”). He goes too.

Scene 5. Porsenna and Muzio appear with the royal guards and Etruscan soldiers. Although Porsenna ordered that the Roman women be carefully guarded, Clelia helped them escape. As the soldiers search the gardens, Muzio Porsenna points out how much the Romans despised Tarquinio. The soldiers come back with no results.

Scene 6. Valeria sings about her hope for peace with the gardeners (Valeria and choir: “Sorga l'Alba, e serbando i suoi fiori”). Porsenna advises her that she could secure the peace herself at any time if she agrees to marry him. Valeria rejects this again and assures Muzio of her continued love (Valeria: “A te il mio amor mi diè”).

Scene 7. Tarquinio pulls Orazio, whom he blames for the hostages' flight. Orazio indignantly rejects this. Porsenna, however, agrees with Tarquinio, since Orazio had given him his word of honor that the hostages would not flee. He asks Orazio to surrender his sword and allow himself to be arrested. Orazio draws the sword, however, to defend his freedom against the soldiers. Only Muzio succeeds in appeasing him. Publio Valerio should decide on his guilt. Porsenna agrees. Orazio advises Tarquinio and Porsenna to take good care of him, because it will soon become clear who is the real culprit (Orazio: "Guarda Orazio: e tu marcato").

Scene 8. After Muzio has restored his trustworthiness, he points out that Tarquinio lacks important virtues for the throne, namely “just mildness”, “pure innocence” and “pious goodness” (Muzio: “Mal brama il Regno”). Muzio goes.

Scene 9. Tarquinio asks Porsenna to punish Muzio too, but Porsenna sees no reason to do so. When Erminio reports the arrival of Publio Valerio, Porsenna confirms his intention to act virtuously ("Sia felice in me l'amor"). He goes to meet Publio Valerio. The Etruscan soldiers are already looking forward to the upcoming peace (chorus: "Pace si brama? Pace si speri").

Scene 10. Publio Valerio appears with the lictors and Roman knights to judge Orazio. He takes Clelia with him, who in return gives Porsenna for a hearing. Clelia explains to them that she wanted to achieve the same fame as Orazio and Muzio through her deed. She is ready to take on the guilt associated with it. Then she describes in detail the sequence of her escape, on which she had to swim across the Tiber with the other women. Orazio did not participate. Instead, Tarquinio's attack was the real cause of their flight. As proof, she shows those present the sword Tarquinio had brought with her. Porsenna is so impressed by her courage that he gives her freedom and Tarquinio declares his contempt. There is now a realistic prospect of peace. Publio Valerio, however, stipulates that Porsenna obeys Roman law and refrains from marrying Valeria. The decision rests with Porsenna, and Publio Valerio vividly depicts his conflict in a comparison with a sailor in a storm (Publio Valerio: “Sei nocchier, che può, s'ei vuole”). While the Etruscan soldiers are already longing for peace, the Roman soldiers conjure up the military strength of Rome (chorus: “Pace, Porsenna, pace” - “Guerra, Valerio, guerra”). After some hesitation, Porsenna agrees. In conclusion, Publio Valerio praised Orazio's strength, Muzio's persistence and Clelia's courage. He promises to hand over his family property to Tarquinio. Tarquinio surrenders his claim to the throne, and Porsenna swears eternal peace to Rome and true friendship to Valeria. A splendid grotto (“grottesca”) appears, which is transformed into a large triumphal arch, on which the penates and the genius of Rome are shown (Tutti: “Fan Costanza, e Fortezza i somi Eroi” - “Al Romano Genio invitto ").

License

The genius of Rome descends from the triumphal arch and praises the goddess Vesta, whom he reveals as the image of the Empress Elisabeth ("Elisa"). It is so large that people can only pay homage to it in symbolic form (Il genio di Roma: “Tal tu sei, che non arriva”). Instead of the Roman victory, the birthday of the empress is celebrated (Tutti: “Grande AUGUSTA, a 'tuoi Natali”).

Ballet of the Penates of Rome

In the final ballet, the Penates dance and sing together with the allegorical figures of love for peace (“Amor della Pace”) and general happiness (“Pubblica Felicità”) and cheer Vesta / Elisa (chorus: “Che bel piacer”).

layout

Costanza e fortezza is one of the main works by Johann Joseph Fux, who was already old at the time . His contrapuntal style suited the emperor's preferences. He also developed Italian, French and German stylistic elements in this opera in a personal way. Additional elements are “ Siciliano melodies as a reminder of the Venetian-Neapolitan opera tradition and simple folk song quality”. An Etruscan choir uses chromatic lines to represent “barbarism”.

Instrumentation

The orchestral line-up for the opera includes the following instruments:

- Woodwinds : two recorders , two oboes , bassoon

- Brass : eight trumpets , four of which are high clarinet

- four timpani

- Strings

- Basso continuo

Work history

Costanza e fortezza was published once on August 28, 1723 as a "coronation opera " on the occasion of the coronation of Emperor Charles VI. listed as King of Bohemia in Prague. The process corresponded to that of a courtly ceremony and was carried out to glorify the monarch with the greatest possible pomp. In the courtyard of Prague Castle , Giuseppe Galli da Bibiena , who also created the stage decorations, built an open-air theater specially for this purpose. In addition to the highest dignitaries of the empire, “audiences by the thousands” also flocked to the performance.

The open-air theater had a total size of approx. 40 by 120 meters. The stage was 20 meters wide and 70 meters deep. It was bordered on the sides by two domed towers, on whose balconies two trumpet choirs could produce stereo effects. The huge backdrops remained on the stage during the performance. They could be opened and closed like book pages. For the appearance of the deities there were miniature stages that could be lowered through trap doors and opened like altar panels.

At the first performance singing Christoph Praun (Publio Valerio), Gaetano Orsini (Porsenna), Domenico Genovesi (Tito Tarquinio), Rosa Borosini d'Ambreville (Valeria), Anna D'Ambreville (Clelia), Francesco Borosini (Orazio), Pietro Cassati ( Muzio), Giovanni Carestini (Erminio), Gaetano Borghi (Il fiume Tevere and Il genio di Roma), Giovanni Vincenzi (soprano) and Anton Werndle (bass). Supported by other Prague musicians, the most outstanding members of the Viennese court orchestra played, including Francesco Bartolomeo Conti , Gottlieb Muffat and Johann Georg Reinhardt , as well as virtuosos such as Johann Joachim Quantz , Carl Heinrich Graun and Silvius Leopold Weiss . According to Quantz, there were a total of a hundred singers and two hundred instrumentalists. Antonio Caldara was the musical director . The ballets were choreographed by Pietro Simone Levassori della Motta (first and third act) and Alessandro Phillebois (second act).

Numerous contemporary sources reported on the performance. Johann Joachim Quantz, one of the contributors, wrote in his autobiography:

“In the meantime I traveled to Prague in Julius of the 1723rd year, in the company of the famous lutenist Weiss, and the royal Prussian Capellmeister, Herr Graun, to attend the great and splendid opera, which at the coronation of Kayser Carl the Sixth, took place there in public Heaven, was performed by 100 singers and 200 instrumentists. It was called: Costanza e Fortezza. The composition was by the Kayserl. Ober-Capellmeister, the famous old Fux. It was more ecclesiastical than theatrical; but very splendid. The concertiing and binding of the violins against each other, which occurred in the ritornelas, although it consisted largely of movements that often looked stiff and dry enough on the paper, nevertheless did a very good job here, on the whole, and with so numerous instrumentations good, yes, much better effect than a more gallant and many small figures, and quick notes of graceful singing, in this case, would have done. [...]

The many choirs in the Prague Opera also served, in the French style, for ballets. The scenes were all lit up translucently.

Because of the number of exporters, the imperial Capellmeister Caldara set the tone. But old Fux himself, whom the Kayser had had to be carried from Vienna to Prague in a sedan chair because he was burdened with the Podagra, had the pleasure of listening to this unusually splendid performance of his work, not far from the Kayser.

Among the main or concert singers, not a single one was mediocre, they were all good. [...]

All these singers were in real imperial service. From the Viennese orchestra, however, only a few twenty people were brought along. The other instrumentists were sought out in Prague and consisted of students, members of some of the count's chapels, and foreign musicians. […] The choirs were made up of students and church singers from the city. Because the entrance to the opera was barred because of the large number of people present, many, including people of high class; so my two companions, and I, also let us be recruited to the orchestra. White played the theorbo, Graun the violoncello, and I the hoboe, as a ripienist. At the same time we had the opportunity to hear the opera all the more often because of the many rehearsals that were required. "

The score was kept in the Imperial and Royal Court Archives in Vienna for a long time. Egon Wellesz created a new edition from it, which was published in 1910 as Volume 17 of the series Monuments of Music in Austria . In 1959 it was reissued in this series as volume 34/35 and reprinted in 2014 by music production Höflich . The original is now lost.

The Cloelia story was already known to a large audience before Costanza e fortezza through the pseudo-historical novel Clélie, histoire romaine by Madeleine de Scudéry (ten volumes between 1654 and 1660). It also became the subject of various other libretti such as Mutio Scevola by Nicolò Minato (1665), Clelia by Friedrich Christian Bressand (1695), Muzio Scevola by Silvio Stampiglia (also 1695), Porsenna by Agostino Piovene (1712) and Clelia by Giovanni Claudio Pasquini . In 1762 Pietro Metastasio took it up again in his libretto Il trionfo di Clelia .

Performances in recent times

After the world premiere, the opera was rarely performed. In 1938 it was given both under the direction of Otakar Jeremiáš at the Prague Conservatory and under Werner Josten at Smith College in Northampton (MA). Both performances were shortened. On the occasion of the latter performance, a piano reduction by Gertrude Parker Smith was published in 1936.

On October 26, 1991 there was a largely complete concert performance in the Great Musikvereinssaal in Vienna with the ensemble “Gradus ad Parnassum”, the trumpet consort Friedemann Immer and the ORF Vienna choir. It sang David Thomas (Publio Valerio), Michael Chance (Porsenna), Agnès Mellon (Tito Tarquinio), Elisabeth von Magnus (Clelia), Douglas Nasrawi (Orazio, Il Fiume Tevere and Il Genio di Roma), Claudio Cavina (Muzio) and Mieke van der Sluis (Erminio).

In 2003 the work was performed at the Prague Spring Music Festival .

On July 31, 2015 there was a staged performance for the first time in the riding school in Světce near Tachov as part of the European theater season Pilsen ( European Capital of Culture 2015) with a historically accurate stage construction based on the model of the Baroque theaters in Český Krumlov , Litomyšl and Drottningholm Palace . The ensemble “Musica Florea” performed under the direction of Mark Štryncl. The singers were David Nykl (Publio Valerio), Martin Ptáček (Porsenna), Michaela Šrůmová (Tito Tarquinio), Markéta Cukrová (Valeria), Stanislava Jirků (Clelia), Roman Hoza (Orazio), Sylva Čmugrová (Muzio), Alice Martini ( Erminio), Matúš Mazár (Il fiume Tevere and Il genio di Roma). In this arrangement, however, the work does not end with the apotheosis of Empress Elisabeth, but with that of the First Czechoslovak Republic .

literature

- Reinhard Strohm : Costanza e fortezza: Investigation of the Baroque Ideology. In: Daniela Gallingani (Ed.): I Bibiena: una famiglia in scena: da Bologna all'Europa. Alinea Editrice, Florenz 2002, ISBN 88-8125-540-5 , pp. 77-91 ( limited preview in Google book search).

Web links

- Costanza e fortezza : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto (Italian), Vienna 1723. Digitized by Gallica

- Work data for Costanza e Fortezza based on MGG with discography at Operone

- Jirí Hilmera: Costanza e Fortezza - Giuseppe Galli-Bibiena and the Baroque Theater in Bohemia

- Jirí Hilmera: Mise en scène de l'opéra solennel "Costanza e Fortezza" au château de Prague en 1723 (French)

Remarks

- ↑ The exact date is not explicitly given. In the literature there is usually the statement “around 500 BC. According to legend, the siege took place in 508 BC. Chr. Instead. According to the libretto (first act, scene 2) the action takes place on the day of Vesta , i. H. on June 9 (see table of contents in Piper's Encyclopedia of Music Theater ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Herbert Seifert: Costanza e Fortezza. In: Grove Music Online (English; subscription required).

- ^ A b c Jacques Joly: Les fêtes théâtrales de Metastasio à la cour de Vienne, 1731–1767. Pu Blaise Pascal, 1978, ISBN 978-2-845160194 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Reinhard Strohm: Costanza e Fortezza. In: Piper's Encyclopedia of Musical Theater. Vol. 2. Works. Donizetti - Henze. Piper, Munich and Zurich 1987, ISBN 3-492-02412-2 , pp. 300-302.

- ^ Ulrich Schreiber : Opera guide for advanced learners. From the beginning to the French Revolution. 2nd Edition. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2000, ISBN 3-7618-0899-2 , p. 268.

- ^ Costanza e Fortezza. In: Kurt Pahlen : The new opera lexicon. Seehamer, Weyarn 2000, ISBN 3-934058-58-2 , p. 210.

- ↑ a b c d Bradford Robinson: Foreword to the score edition of the opera. Music production Höflich, Munich 2012.

- ↑ August 28, 1723: “Costanza e fortezza”. In: L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia ..

- ↑ Mr. Johann Joachim Quantzen's curriculum vitae, designed by himself. In: Historically-critical contributions to the recording of the music, Vol.1. Pp. 216-220 ( online ).

- ^ Don Neville: Trionfo di Clelia, Il. In: Grove Music Online (English; subscription required).

- ^ Johann Josef Fux. In: Andreas Ommer: Directory of all opera complete recordings. Zeno.org , Volume 20, p. 4964.

- ↑ Costanza e Fortezza on operabaroque.fr , accessed on 14 July 2016th

- ↑ European theater season in Pilsen 2015 on onetz.de , accessed on July 14, 2016.

- ^ Costanza e fortezza. Event announcement on plzen2015.cz , accessed on July 14, 2016.

- ^ Costanza e Fortezza on the website of the ensemble "Musica Florea" (Czech) , accessed on July 14, 2016.