Political iconoclasm

Political iconoclasm (also monument fall ) describes the politically motivated removal or destruction of symbols of rulership or images of rulers , mostly in connection with the fall of a ruler or the collapse of a political system. The aim is to make the loss of power symbolically visible, or to permanently remove the symbols of a lost power from public perception.

term

The political iconoclasm is conceptually based on the religious iconoclasm, but represents an abstraction of the same. The understanding of political icons is broader: So it is not only icons in the sense of images of saints , but mostly images or images that are associated with a be created or staged with a certain intent of representation and accordingly disseminated and received. Statues of rulers or, for example, monumental magnificent buildings symbolically represent the system of rule and its power . In a political context, iconoclasm can also be described synonymously with iconoclasm . Vandalism is often used synonymously, but this is to be rejected because of the arbitrariness of the act of destruction inherent in this term.

history

Antiquity and antiquity

In ancient Egypt , Pharaoh Thutmose III. eradicate the mortuary temple of his stepmother Hatshepsut from images and evidence of her existence and replace her name with that of other pharaohs. In ancient Rome in particular , iconoclastic acts in the course of the damnatio memoriae can be observed as a means of historical politics. Here, the ruler's portraits were damaged, destroyed or sunk in the Tiber .

middle Ages

For the Middle Ages , the politically motivated destruction of images in the sense of the monument collapse did not play such a major role. The removal of a statue of Charles I of Anjou in Piacenza, ordered by Henry VII in 1312, can be cited as an example.

Modern times and modernity

In modern times, political iconoclasm often occurs in the context of revolutions . Examples include the storming of the Bastille in 1789 during the French Revolution , the storming of the Winter Palace as a prelude to the October Revolution in 1917, the fire in the Reichstag in the wake of the National Socialist seizure of power in 1933 and the demolition of Stalin monuments after the collapse of the Eastern bloc .

During the Paris Commune , the Colonne Vendôme , a victory column in honor of Napoleon I , was torn down by the Communards on May 16, 1871. After the uprising was put down, the painter Gustave Courbet , also a communard, was held liable for it and had to bear the costs of its rebuilding.

James Noyes sees iconoclasm as an accompaniment to the establishment of the modern secular nation state, whose new elites oppose competing religious ties.

Since the end of the Second World War

National Socialist symbols after 1945

After the end of the Second World War , the symbols of National Socialism , such as images of Hitler or swastikas , were removed from public space almost everywhere. In Germany, the use of such symbols, with a few narrowly defined exceptions, as the use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations is a criminal offense. In Austria there is a comparable regulation with the Badge Act .

Removal of socialist souvenirs after 1989/90

Similar to the French Revolution, the fall of the Berlin Wall , in which people referred to by the media as " wallpeckers " destroyed parts of the building with hammers and chisels, can be seen as the symbolic fall of a monument to socialist rule.

The collapse of socialism led to the removal of numerous monuments, but also buildings of the old regime. A prominent example is the demolition of the Berlin Lenin Monument in Berlin-Friedrichshain in 1991, whereby the head was first removed and buried together with the remaining parts of the statue. The Palace of the Republic as a GDR building icon was also torn down.

terror attacs at the 11th September 2001

James Noyes also considers the destruction of the World Trade Center to be a form of political iconoclasm.

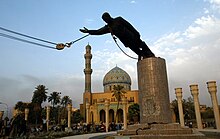

The fall of Saddam Hussein

As part of Operation Iraqi Freedom , the United States went to great lengths to portray military operations as liberation. Accordingly - not least through the embedded journalists - an attempt was made to achieve a visualization of the military operation with positive connotations . For the success of Operation Iraqi Freedom , in addition to military successes, the images of the symbolic dismantling of the Saddam regime were particularly important. This disempowerment took place in several steps. Initially, a symbolic disempowerment took place by conquering the palaces and falling or grinding the statues. An intermediate step was the public display of the two sons Udai Hussein and Qusai Hussein , who were killed in a firefight, in front of the international press. Saddam Hussein was arrested and executed.

Of decisive importance for the warring coalition, however, were the preliminary photos showing the fall of the system's insignia. The conquest or destruction of the symbols of the Saddam Hussein regime was thus one of the primary goals of the USA. As a first step, the Allies targeted the palaces of Hussein in Basra . During the conquest of Baghdad in early April 2003, the US Army occupied the Palace of the Republic on April 7, 2003. The significance of the events for the strategists in Washington, DC only grew through the press photos of the occupation. Another very decisive “act of symbolic disempowerment” was the fall of the Saddam statue on Baghdad's Firdaus Square on April 9th. The most famous photo of the fall of the statue, on which it is pulled from the base with ropes and chains, suggests through the image detail that the Iraqi people themselves brought the monument down. De facto, however, this did not succeed, instead the sculpture was knocked off with the help of an American military vehicle. Goran Tomasevic's photo was chosen in order to get positive coverage and the desired impression in public . This image was received in the media as an “icon of the American victory”, although the dictator was not captured until much later.

Contested memory of colonialism and slavery

In the wake of protests against the racial discrimination of the population in 2020 were in the United States statues and other monuments attacked, damaged or destroyed. The historical figures depicted are often associated with the past of slavery and colonialism .

This includes memorials to the memory of the Confederate States of America at the time of the American Civil War . The removal of Confederate generals from public space has been a controversial issue since 2015. In 2017, demonstrations between supporters and opponents of the removal of the equestrian statue of Robert Edward Lee led to violent riots in Charlottesville .

In Europe, as a result of the American protest movement in 2020 in Belgium , France and the UK, there were attacks on monuments associated with the past of slavery and colonialism. The debate in Germany ties in with the importance of the German colonies in the public culture of remembrance .

literature

- Sophie Calle : The Distance / The Detachment . Exhibition catalog. Berlin 1996.

- An art project about the removal of symbols of the ex-GDR in Berlin.

- Uwe Fleckner, Ed .: Handbook of Political Iconography. Munich 2011.

- Gamboni, Dario: Destroyed Art. Iconoclasm and vandalism in the 20th century, Cologne 1998.

- Großbölting, Thomas / Schmidt, Rüdiger (ed.): The death of the dictator. Events and memories in the 20th century, Göttingen 2011.

- Müller, Marion G .: Basics of visual communication, Konstanz 2003.

- Gerhard Paul : The image war. Stagings, images and perspectives of the “Operation Irakische Freiheit”, Göttingen 2005, pp. 96–110.

- Purdum, Todd S .: A Time Of Our Choosing. America's War In Iraq, New York 2004.

- Winfried Speitkamp (ed.): Monument fall. On the history of the conflict of political symbolism . Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1997, ISBN 3-525-33527-X

- Christine Tauber: Iconoclasms of the French Revolution. The vandalism reports of the Abbé Grégoire, Freiburg i. B., 2009.

- Ulrich Tilgner : The staged war. Deception and Truth in the Fall of Saddam Hussein, Berlin 2003.

- Martin Warnke : Iconoclasm. The destruction of the work of art . Frankfurt am Main, 1988.

Web links

- Dolezych, Alexandra: Herrscherbilder, in: BPB Online (Ed.): Bilder in Geschichte und Politik, 2007.

- Mertin, Andreas: "Destroy the icons"! On the renaissance of political iconoclasm, in: Magazin für Theologie und Ästhetik, Issue 23, 2003

- USA Today: Saddam's statue comes down , picture gallery from the fall of the Saddam Hussein statue on Firdos Square in Baghdad on April 9, 2003

- Winfried Speitkamp (ed.): Monument fall. On the history of the conflict of political symbolism full text and PDF at Digi20

- Strahl, Tobias: Cultural heritage in national conflicts in: DenkmalDebatten, website of the German Foundation for Monument Protection, 2015

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Review of the monument fall. On the history of the conflict of political symbolism

- ↑ Denkmalsturz afrika-hamburg.de

- ↑ On terminological differentiations, see Gamboni, Dario: Destroyed Art. Iconoclasm and vandalism in the 20th century, Cologne 1998, p. 17 ff.

- ↑ Dolezych, Alexandra: "Herrscherbilder" , in: BPB Online (ed.): Pictures in History and Politics, 2007.

- ↑ Manfred Schneider: Imaginations des Staats. In: Rudolf Behrens and Jörn Steigerwald (eds.): The power and the imaginary. A cultural affinity in literature between early modern times and modern times . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005, limited preview in the Google book search.

- ^ Georges Riat: Gustave Courbet. Parkstone International, New York 2012, pp. 215-234.

- ↑ James Noyes: The Politics of Iconoclasm: Religion, Violence and the Culture of Image-Breaking in Christianity and Islam. London 2013.

- ↑ See Calle, Sophie: The Distance / The Detachment, Berlin 1996.

- ^ Noyes 2013.

- ^ Paul, Gerhard: The image war. Stagings, images and perspectives of the "Operation Iraqi Freedom", p. 96 f.

- ↑ See the photo gallery with photos by John Moore, Terry Richards and Simon Walker: "Saddam's Palaces"

- ↑ Schmidt, Christopher: Peace to the huts! War in the Palaces !, in: Sueddeutsche Zeitung, April 9, 2003.

- ↑ Cf. Rageh Omaar: A Baghdad Diary, in: Beck, Sara / Downing, Malcom (ed.): The Battle for Irak. BBC News Correspondents on the War Against Saddam, Baltimore 2003, pp. 121-132.

- ↑ See Paul, Der Bilderkrieg, p. 101; see. also the photo gallery: USA Today: Saddam's statue comes down

- ↑ Großbölting, Thomas: Saddam Hussein. The double death of the dictator, in: Großbölting, Thomas / Schmidt, Rüdiger (ed.): The death of the dictator. Events and memories in the 20th century, Göttingen 2011, pp. 303–317, p. 305.

- ^ Deutsche Welle: Columbus statue beheaded in Boston, another toppled in Richmond. June 10, 2020, accessed on June 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Deutsche Welle: Belgium: King Leopold II statue removed in Antwerp after anti-racism protests. June 9, 2020, accessed June 11, 2020 .

- ^ Philippe Bernard: Du sud des Etats-Unis à la France, des statues déboulonnées pour une histoire partagée. Le Monde, June 12, 2020, accessed June 12, 2020 .

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk Nova: "As long as the monuments stand unbroken, this worldview will continue to be glorified". June 8, 2020, accessed June 15, 2020 .

- ↑ Public affairs, August 28, 2002 ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ). accessed on January 7, 2015