The process

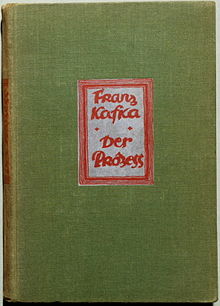

Der Proceß (also Der Proceß or Der Prozess , title of the first edition: The Trial ) is one of three unfinished and posthumously published novels by Franz Kafka , along with Der Verschollene (also known as America ) and Das Schloss .

History of origin

During the creation of this unfinished work - from summer 1914 to January 1915 - significant events took place in the author's life. These come into play in an interpretation of the novel based on production conditions: In July 1914, the engagement to Felice Bauer was dissolved. For Kafka, this event was associated with a feeling of being accused, a final discussion in the Berlin hotel Askanischer Hof in the presence of Felice's sister Erna and Felice's girlfriend Grete Bloch , with whom Kafka had exchanged a captivating correspondence, Kafka felt as a “ court of justice ”. Shortly afterwards, Kafka began working on the trial . On July 28, a month after the assassination in Sarajevo , the monarchy declared Austria-Hungary war on Serbia, from the First World War was. From autumn 1914, Kafka lived for the first time independently of his parents in his own room.

At first, Kafka's work on the trial progressed rapidly - around 200 manuscript pages were created in two months - but soon came to a standstill. Kafka was now a. a. with the story In the penal colony . The process developed in a non-linear sequence. It can be proven that Kafka first wrote the opening and the final chapters (which Max Brod sorted into this place) and continued to work on individual chapters in parallel. Kafka wrote the trial in notebooks, which he also used for writing down other texts. He separated out the pages belonging to the process and arranged them according to chapters and fragments, without defining any particular order of the parts.

At the beginning of 1915, Kafka interrupted work on the novel and did not resume it (apart from a brief attempt in 1916). As early as November 1914, Kafka wrote: “I can no longer write. I am at a final limit, which I should perhaps sit in front of for years and then perhaps start a new story that remains unfinished. "

characters

- Josef K.

- Josef K., 30 years old, is an authorized signatory at a bank . He lives alone, his lover Elsa and a regular round table are enough for him as human contacts . K's father has already died, his mother only appears in a fragment. There is no emotional connection to her.

- The arresting people

- The guards, called Franz and Willem, inform Josef K. of his arrest and initially hold him in his room. A nameless overseer harshly rejects K.'s rebellion. Three gentlemen who were also present, subordinate colleagues from the bank in which K. worked, named Rabensteiner, Kaminer and Kullych, were assigned to accompany K. to work after his arrest.

- Miss Elsa

- Miss Elsa works as a waitress . During the day she receives male visitors, K. goes to see her once a week. Later in the first conversation with Leni she is referred to as K.'s lover. (She is not a direct acting person in the context of the novel, but is only mentioned by Josef K.)

- Mrs. Grubach

- Mrs. Grubach is K.'s and Miss Bürstner's landlady. She prefers K. over the other tenants because he has loaned her money and she is therefore in his debt.

- Miss Bürstner

- Miss Bürstner has only recently been a tenant of Frau Grubach and has little contact with K. However, the night after his arrest he lies in wait for her in front of her room and, after a conversation, forces her to kiss her. She is interested in the machinations of the court because in a few weeks she will be starting a job as a secretary in a law firm.

- The bailiff's wife

- She has a special erotic charisma, so that both a law student and the examining magistrate use her for love services. She also offers herself to Josef K. and tells him something about the bizarre world of the court that meets in a poor apartment building.

- Advocate grace

- The lawyer Huld is an acquaintance of K.'s uncle and is physically weak and bedridden due to an illness. He defends himself from his sick bed. His statements are excruciatingly drawn out. K. soon withdraws his defense from him.

- Leni

- Leni is the attorney's servant who takes care of the lawyer very devotedly during his illness. She appears very playful and sociable. During his first visit, Leni lures K. into a room next door to approach him. She seems to have important information about the court system.

- Uncle Albert K./Karl K.

- K's uncle lives in the country. When he learns of Josef K's trial, he travels to town to help him. He introduces K. Advokat Huld. His name is not entirely clear: At the beginning of the chapter Der Unkel / Leni he is called Karl, later (by the lawyer Huld) Albert.

- Erna

- Erna is K.'s cousin and the daughter of uncle Albert (Karl). She wrote her father a letter telling about K's trial. (She is not a direct acting person in the context of the novel, but is only mentioned by the uncle.)

- Titorelli

- As a court painter, Titorelli is privy to certain court proceedings. Through his personal contact with the judges, he could mediate between K. and the court. But Titorelli is firmly convinced that no one - including himself - can convince the court of the innocence of a defendant.

- Businessman block

- The businessman Block is a short, skinny man with a full beard who is also being tried. Block spends the night in the house of the lawyer Huld in order to be available at any time for a conversation with the lawyer, and humbles himself in front of the lawyer.

- Prison chaplain

- The prison chaplain tells K. the parable Before the Law . He tries to explain to K. that although there are different interpretations of the parable, he does not agree with any. K. is also not satisfied with the unclear proposed solutions. After emphasizing several times that none of the interpretations have to be true, but that there are only different interpretations, K. refrains from finding a possible solution himself. The chaplain knows that K's trial is not going well and that it will end badly.

- Deputy Director

- As a superior, the deputy director oversees K's activities in the bank and works closely with him. The relationship with the deputy, who always appears extremely correctly, becomes a cause for concern for K., as the process puts a lot of strain on him and he can devote less and less care to his daily work.

- director

- The director is a kind person with an overview and judgment, who treats K. favorably and gives fatherly advice.

- Prosecutor Hasterer

- Although much older and more resolute than K., a close friendship develops between the two. K. regularly accompanies the prosecutor after the regulars' table for an hour with schnapps and cigars and is sponsored by him.

- The beater

- A court clerk who beats up the two guards because Josef K. had loudly complained about them at his first hearing.

- The executors

- Two nameless gentlemen, pale, fat and with “cylinder hats” lead Josef K. to a quarry and kill him with a stab in the heart.

action

overview

The bank authorized representative Josef K., the protagonist of the novel, is arrested on the morning of his 30th birthday without being aware of any guilt. Despite his arrest, K. is still allowed to move around freely and continue his work. He tries in vain to find out why he was charged and how he could justify himself. In doing so, he comes across a court that is beyond his grasp, the offices of which are located in the attics of large, poor tenements. The women who are connected to the world of justice and whom K. tries to recruit as “helpers” exert an erotic attraction on him.

Josef K. tries desperately to gain access to the court, but he does not succeed either. He is increasingly concerned with his process, although initially he intended the opposite. He gets further and further into a nightmarish labyrinth of a surreal bureaucracy. He penetrates ever deeper into the world of judgment. At the same time, however, the court also penetrated more and more Josef K's life. Whether a process of any kind is actually progressing secretly remains hidden from both the reader and Josef K. The same applies to the judgment: K. does not find out, but he feels himself that his time is up. Josef K. submits to an intangible, mysterious verdict without ever finding out why he was accused and whether there is actually a court judgment on it. On the eve of his 31st birthday, Josef K. is picked up by two gentlemen and stabbed to death "like a dog" in a quarry.

According to chapters

(According to the Reclam edition.)

arrest

When Josef K. wakes up in his room on the morning of his 30th birthday, the cook of his landlady does not bring him breakfast as usual. Instead, K. is surprised and arrested by two men who briefly tell him that he has been arrested from now on. The two (Franz and Willem, known as the "guard") claim to come from an authority and claim that they cannot and should not tell him why he is under arrest.

K. initially assumes a bad joke by his colleagues. However, over time, he realizes that this is not the case. He hopes for a more detailed explanation or understanding from the guard, an educated man who, however, brusquely turns K. back into the role of the arrested. However, he gives K. to understand that this arrest will not affect his usual way of life or his professional practice. Although K. is initially annoyed, the arrest seems to him to be “not that bad”.

The scene of this conversation with the supervisor is not K.'s room, but that of the absent young neighbor, Miss Bürstner. Also present are three subordinate employees from the bank in which K. works. First you rummage around in the room and finally accompany K. to the bank.

Conversation with Mrs. Grubach / then Miss Bürstner

Josef K. goes back to his pension after work to apologize to his landlady Ms. Grubach and the neighbor Miss Bürstner for the inconvenience caused by his arrest: the three employees were visible in the pictures of Miss Bürstner rooted. Miss Bürstner doesn't come home until very late in the evening. K. lies in wait for her and surprises her in the hallway.

He then informs her of the incident in her room. For the demonstration, K. plays what happened that morning and calls out his name loudly and theatrically. As a result, Frau Grubach's nephew, a captain, who is sleeping in the next room, wakes up and knocks on the door to meet Josef K.'s and the fräulein's horror.

Miss Bürstner asked several times to end the conversation because she was very tired from a long day at work. K. says goodbye to her. Suddenly he kisses the lady, insistently and greedily, on the neck, face and mouth.

First investigation

For the Sunday after his arrest, Josef K. is summoned to an investigation by telephone without being given a time. He will then be given details about the examinations to be expected in the future. K. did not ask who turned to him exactly.

So on Sunday morning he went to the address where the investigation was to take place, an old apartment building in a run-down neighborhood. Once there, K. has to search for the courtroom for a long time. It turns out to be a small room in a bailiff's apartment. Many similarly dressed people have already gathered, Josef K. is too late. The examining magistrate mistakenly greeted K. as a "carpenter". His only court document is a small, tattered booklet that K. later stole from him. K. tries to win over the present officials of the court with a speech about the absurdity of the court, the injustice of his arrest and the corruption of the guards. However, he gets lost in long-winded descriptions. So the audience's attention slips away and turns to a pair of lovers screeching lustfully in a corner.

The crowd is divided into two different parties (the left and the right). During his speech, K. discovers that the judge is giving the audience a sign. Then he registers that both parties, like the examining magistrate, all without exception wear the same badge on the collar of their coat. He is excited, sees himself surrounded, becomes rabid and sees the court as a corrupt gang. The examining magistrate pointed out that he had deprived himself of the advantage that interrogation would bring the arrested person. K. describes everyone as rags and indicates that he will refrain from further interrogations.

In the empty meeting room / The student / The offices

Without being asked, Josef K. went back into the building the following Sunday, assuming that the hearing would continue. In the apartment to which the courtroom belongs, he meets the wife of the bailiff who lives there. Outraged, he recognizes in her the woman who a week earlier had so lecherously with her lover in the courtroom. She flirtatiously offers K. to stand up for him, saying that she liked his speech. She hopes that he can bring improvements to the court system. After some initial reluctance, she also shows him the examining magistrate's books. It turns out that these are full of pornographic drawings. The woman obviously has a relationship with the examining magistrate, whose zeal she praises because he continues to write long reports well into the night after the negotiations. There is also the law student Berthold, who desires her fiercely. When he finally appears himself, he catches the woman and, against K.'s resistance, carries her to the examining magistrate. She, who at first showed herself so inclined towards K. and even wanted to flee with him, willingly lets it happen.

Shortly afterwards, the bailiff and husband of the woman in question appears, complains bitterly about her infidelity and invites Josef K. to take a tour of the offices. These are apparently always located in the attics of various apartment buildings. Josef K. is amazed at the poor conditions there. Some visibly humiliated defendants sit on long wooden benches, waiting to be let into the departments by the officers. A very insecure defendant whom K. speaks to is waiting for his evidence to be granted. Josef K. thinks something like this is unnecessary in his own case.

Suddenly K. becomes ill and he loses all his strength, which is justified by the bad air in the office. He collapses and is then led outside by a girl and an elegantly dressed man (the information provider). After leaving the office, K's physical well-being is suddenly restored.

The beater

In a junk room of his bank, Josef K. witnessed the whipping of the two guards who had arrested him and whom he had accused of corruption in his speech in the courtroom. Since he feels guilty for the suffering of the two, K. tries to bribe the beating, a half-naked man dressed in leather. However, he turns down the offer. When Franz, one of the two guards, screams under the beatings, K. withdraws from the situation. He fears that the bank clerks may have noticed the guard's scream and surprise him in the lumber room.

When Josef K. opens the door to the junk room in which the punishment was carried out again the next day, he still finds the same scene, as if time had stood still in the room. Again he evades responsibility and orders two bank clerks to clear out the room.

The uncle / Leni

Josef K.'s uncle and former guardian Karl / Albert vom Lande visits K. in the bank. He had learned in a letter from his teenage daughter Erna, a boarding school student, that K. had been charged. The uncle is very excited about the trial and goes with K. to his lawyer and friend Huld, who has good relations with some of the judges.

On the first visit, Huld is sick in bed, but is ready to represent K's cause, which he has already heard of through his relevant professional contacts. Also present at Huld is the office director (obviously the director of the ominous court offices) as well as Huld's maid, the young Leni. K. is mentally absent. The thoughts of the three older men on his cause hardly seem to affect him.

Leni lures K. out of the conference room and approaches him suddenly and erotically inviting. At the end of the visit, Uncle K. makes serious accusations that he missed such an important meeting because of “a dirty little thing” .

Lawyer / manufacturer / painter

Josef K., who “never left the thought of the trial”, decides to draft a defense himself, as he is increasingly dissatisfied with the work and the painfully drawn out descriptions of the lawyer Huld in his case. These descriptions also dominate the preparations for the next hearing.

Afterwards K. receives a manufacturer in his office in the bank who knows about his trial and refers K. to the court painter Titorelli. Perhaps he could free him because he had information and influence over judges and officials.

K. finds Titorelli in a small room (his studio provided free of charge by the court) in an attic of a house in another run-down district. The painter explains to him that there are three ways to escape the court, but that K. has no real chance of a “real / real acquittal”, even if he should actually be innocent. Something like this had never happened in his lifetime. But there is still the "apparent acquittal" and the "procrastination". For the apparent acquittal one has to convince a majority of the judges of the innocence of the accused and submit their confirmatory signatures to the court. A defendant could be temporarily acquitted. After an indefinite period of time, however, the proceedings could be restarted and an apparent acquittal would have to be achieved again, because the lowest judges could not finally acquit. Only the “highest court” has this right, which is completely inaccessible. In the event of a “drag”, the process is kept at the lowest possible stage. To do this, judges would have to be constantly influenced and the process closely monitored.

The painter promises to talk to some judges in order to win them over to Josef K. However, K. cannot decide on a type of exemption, he still has to think about it. In return, Josef K. bought some of the painter's pictures and left the house through a back door that led to another office in an attic.

Merchant block / dismissal of the lawyer

After months of neglect on the part of his lawyer, K. goes back to grace to terminate him because he sees no noticeable progress in his process. He says that he has never been so concerned about the process as he has been since the time when Huld represented him. However, he also fears that the process will put even more strain on him if he has to do everything himself. At the lawyer he meets another client, Kaufmann Block, against whom a lawsuit is also being conducted, but which has been going on for more than five and a half years. Block has secretly hired five more angular lawyers.

Huld tries to get K. to rethink. He humiliates Block in order to prove how dependent his clients are on him or on his contacts and the possibility of influencing judges and officials. The lawyer from Block lets himself ask for information on his knees and kiss his hand. The chapter closes in the middle of the conversation between the lawyer and his clerk Leni with Block.

In the cathedral

Josef K. receives an order from his superior to show an Italian customer of the bank the art monuments of the city. Shortly before he sets off, he receives a call from Leni, which warns him: “They're rushing you.” Josef K. is supposed to meet the customer in the city's cathedral, but he doesn't come. At this point there are irritations as to whether K. came to the appointment on time and whether it is 10 o'clock (as the logic demands) or 11 o'clock (as the handwriting says). A possible explanation would be a misunderstanding due to K.'s inadequate knowledge of Italian ("who was busy with nothing other than overhearing the Italian and quickly grasping the director's words"), or that the appointment was apparently only one Pretext acted. ("'I came here to show an Italian the cathedral.' 'Leave the trivial,' said the clergyman.")

This clergyman, whom K. meets instead of the Italian, introduces himself as a prison chaplain and knows about K's trial. He tells K. the parable Before the Law (which was the only part of the novel published by Kafka himself) and discusses its interpretations with him in order to make his situation clear to him. However, K. neither sees parallels to his situation, nor does he see any help or meaning in the explanations.

The End

Josef K. is picked up on the eve of his 31st birthday by two men in worn frock coats and top hats, whose mute and formal demeanor reminds him of "[a] lte subordinate actors". He thinks for a moment to offer resistance, but then not only willingly let himself be taken with him, but also determines the direction of the walk himself. They come to a quarry on the outskirts of the city, where Josef K. is being executed: the gentlemen lean him against a stone, one of them holds him and the other pierces his heart with a butcher's knife. “Like a dog!” Are K's last words.

Fragmentary chapters

- Miss Bürstner's girlfriend

K. writes two letters to Miss Bürstner. A friend of the Bürstner family, who also lives in the guesthouse, moves over to her so that the women can share the room together. The friend tells K. that the miss does not want any contact with K.

- Prosecutor

K. is a regular participant in a get-together with various lawyers. Prosecutor Hasterer is his friend, who also invites him to visit him more often. The director of Ks Bank also registered this friendship.

- To Elsa

K. intends to go to Elsa. At the same time he receives a summons from the court. He is warned of the consequences if he does not obey the summons. K. ignores the warning and goes to Elsa.

- Fight with the deputy director

K. is in the bank. He has a tense relationship with the deputy director. This comes into K's office. K. tries to give him a report. The supervisor hardly listens, but is constantly handling a balustrade belonging to the room, which he ultimately damages easily.

- The House

First of all, it is about the house in which the office is located, from which the complaint against K. is based. Then K's aimless daydreams and tiredness emerge.

- Drive to the mother

After thinking about it for a long time, K. sets off from his bench to see his half-blind old mother, whom he has not seen for three years. His colleague Kullych followed K. with a letter as he left, which K. then tore up.

Form and language

The work is consistently written in emphatically factual and sober language.

The novel is told in the third person ; Nevertheless, the reader learns little of what goes beyond the protagonist's horizon of perception and knowledge ( personal narration ). The first sentence alone could still be assigned to an observer from a higher perspective ( authorial narrator ), as he clearly seems to deny K.'s guilt: “Somebody must have slandered Josef K., because he was arrested one morning without having done anything bad . ”The speech he experienced (“ Somebody had to […] ”) expresses Josef K.'s uncertainty here.

The reader gets an insight into Josef K's thoughts and feelings ( inside view ); at the same time, however, he soon realizes that K.'s interpretation and assessment of situations and people often turn out to be wrong, that is, they are unreliable. Therefore, the reader can never be entirely sure of the truth of the story - especially with regard to the enigmatic world of judgment.

The duplication of events is striking. Two different women from the area around the court approach K. in an erotic and demanding manner. Twice K. felt sick from the air in the courtrooms. The word "Gurgel" is emphasized twice, first when K. attacked Fraulein Bürstner, then when K. was executed. Twice there were irritations with the time, during the first examination and when visiting the cathedral. Two guards report the arrest at the beginning and two executioners carry out the fatal sentence at the end.

interpretation

A clear interpretation of the process is difficult. One possibility is to use the following different interpretative approaches, which can be categorized into five main directions:

- biographical : see genesis

- historical-critical : against the background of societal and social tensions in Austria-Hungary and the beginning of the First World War

- religious : especially in relation to Kafka's Jewish origins

- psychoanalytical : the process is seen as the representation and awareness of an inner process

- politically and sociologically : as a criticism of an independent and inhuman bureaucracy and the lack of civil liberties

When classifying these interpretations, however, the following should be taken into account: Similar to the novel Das Schloss , “diverse studies have been made here that offer valuable insights. But they suffer from the fact that the authors endeavor to force their insights into an interpretative framework that ultimately lies outside the text of the novel ”. Increasingly, later interpreters, z. B. Martin Walser , the return to a text- immanent view. The current works by Peter-André Alt or Oliver Jahraus / Bettina von Jagow go in a corresponding direction.

References to other texts by Kafka

The novel deals with the myth of guilt and judgment, the traditional roots of which lie in Hasidic tradition. The East European Jews is replete with stories of plaintiffs and defendants, the heavenly court and punishment, opaque agencies and incomprehensible charges - dating back motifs that appear in Polish legends and until the 13th century.

First of all, there are many parallels to Kafka's other great novel Das Schloss . The two protagonists wander through a labyrinth that is there to make them fail or seems to have absolutely no relation to them. Sick, bedridden men explain the system lengthily. Erotically loaded female figures turn demanding towards the protagonist.

Closely related to the trial is the story In der Strafkolonie , which was written in parallel to the novel in October 1914 within a few days. Here, too, the delinquent does not know the commandment that he has broken. One person - an officer with a gruesome machine - seems to be prosecutor, judge and executor all rolled into one. But that is exactly what Josef K. had in mind that a single executioner would be enough to arbitrarily replace the entire court.

Three years later, Kafka wrote the parable Der Schlag ans Hoftor . It looks like a short version of the Process novel. A lawsuit is brought for vain or no cause, which leads to an ominous entanglement and inescapable punishment. Doom strikes the narrator casually in the middle of everyday life. Ralf Sudau puts it this way: "A premonition of punishment or perhaps an unconscious request for punishment ... and a tragic or absurd downfall are signaled".

Individual aspects

Brief text analysis

The court faces Josef K. as an unknown, anonymous power. Characteristic of this court, which differs from “the court in the Palace of Justice”, are widely ramified, impenetrable hierarchies. There seems to be an infinite number of instances, and K. only has contact with the very lowest of them. That is why the judgment remains incomprehensible for K. and he cannot fathom its essence despite all his efforts. The statement of the clergyman in the cathedral ("The court doesn't want anything from you. It takes you in when you come and it dismisses you when you leave") does not help here. Could K. simply evade the court? His reality is different. The court remains a mystery to K. and cannot be clearly explained.

Josef K. is confronted with a repellent, consoling world. As in Kafka's parable Before the Law the country man asks the help of fleas, Josef K. seeks the help of women, a painter and lawyers who only pretend their influence and put him off. The people asked for help by K. act like the doorkeeper in the parable already mentioned, who accepts the gifts of the country man, but only to put him off and leave him in the illusion that his actions are beneficial to him.

Variety of interpretations

Similar to the case of Das Schloss, the multitude of interpretations can not be considered conclusively due to the abundance, but only selectively.

The novel can initially be seen as an autobiographical one. (See the opening section on the history of origin.) Consider the similarity of the initials of Fräulein Bürstner and Felice Bauer . The intensive description of the judicial system obviously points to Kafka's world of work as an insurance lawyer. Elias Canetti sees this interpretation .

The contrary view, namely that The Trial does not represent a private fate, but contains far-reaching political-visionary aspects, namely the anticipated view of the Nazi terror, is presented by Theodor W. Adorno .

A synthesis of both positions is provided by Claus Hebell , who proves that the “negotiating strategy with which the court bureaucracy wears down K. in the process is based on ... the defects in the legal relationships of K. u. K. monarchy can be derived ”.

Some aspects of interpretations

In the course of the novel it becomes apparent that K. and the court do not face each other as two entities, but that the internal interdependencies between K. and the world of court are becoming increasingly stronger. At the end of the process "Josef K. understands [...] that everything that happens comes from his ego", that everything is the result of feelings of guilt and punitive fantasies.

The dreamlike component of the events is also important. As in a dream, the inside and the outside mix. There is the transition from the fantastic-realistic to the allegorical- psychological level. K's world of work is also increasingly being undermined by the fantastic, dreamy world. (A work assignment leads to a meeting with the clergyman.)

The sexual references of the act

The protagonist's feelings of guilt are largely due to the view of sexuality as it prevailed at the beginning of the 20th century and how it is reflected in the works of Sigmund Freud . "The sexuality connects in a remarkable way with K.'s trial." The women are siren-like , the representatives of the court full of lustful greed. But in the same way, K. is also full of uncontrolled greed towards Miss Bürstner and succumbs to the temptations offered without resistance.

Furthermore, homoerotic elements can also be recognized in the text. There is K's almost loving, ironic view of his director. The elegant or tight-fitting clothing is mentioned several times, especially by men. A half-naked flogger appears who is reminiscent of a sadomasochistic figure and beats the naked guards.

The trial as a humorous story

Kafka's friends said that he often had to laugh out loud when reading from his work. Therefore it makes sense to look for a humorous side in the process - may its core be as serious and gloomy as possible .

“Because the whole thing is terrible, but the details are strange,” says Reiner Stach, assessing this phenomenon. The judges study pornography books instead of law books, they let women bring them to them like a sumptuous dish on a tray. The executioners look like aging tenors. A court room has a hole in the floor so every now and then a defender's leg protrudes into the room below.

The scene with the old civil servant who, after a long night study of files, throws all arriving lawyers annoyed down the stairs, contains an almost cinematic slapstick character. The lawyers do not want to openly oppose the civil servant and allow themselves to be thrown down again and again until the civil servant is tired and the legal dealings can continue.

Editions

Edition of Brod

The first edition is entitled Der Prozess (see on the title page) and was published on April 26, 1925 by the Berlin publishing house “Die Schmiede”. The work was edited by Kafka's friend Max Brod . Brod viewed the bundles as self-contained text units and therefore classified them as chapters. He also determined the order of the chapters. Brod referred to his memory, because Kafka had read parts of the work to him.

In 1935 and 1946 Brod published expanded editions. In addition, they contain parts of the work in the appendix that Brod saw unfinished as so-called unfinished chapters . In addition, Kafka’s annex contains deleted items.

The editions after 1945 were published with the changed spelling The Trial .

Critical Kafka edition

The edition entitled Der Proceß , which was published in 1990 as part of the Critical Kafka Edition ( KKA ) of the works, offers a slightly modified chapter sequence . This edition was edited by J. Born and others and was published by Fischer Verlag.

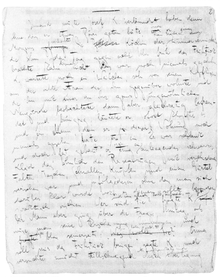

Historical-critical edition

As the beginning of the historically critical Franz Kafka edition ( FKA ) by Roland Reuss in collaboration with Peter Staengle , the third important edition with the title Der Process was published. The 1997 edition is based on the realization that the manuscript is not a completed work. The aim of preserving the original form of the text and the form of the handwriting is reflected in the way the edition presents the text. On the one hand, there is no sequence of the bundles, and on the other hand the bundles are not published in book form. Instead, each of the 16 bundles is reproduced in a booklet. On each double page of the booklet, the facsimile of a manuscript page and its legend are juxtaposed. On the basis of the facsimile, every reader can judge Kafka's deletions, some of which are not unambiguous, since there are no interventions by the editor, as was the case with the Critical Edition and the edition provided by Brod.

Edition by Christian Eschweiler

Eschweiler changed the sequence of chapters and regards Josef K's dream chapter as the climax of the development process. Eschweiler is of the opinion that the cathedral chapter divides the novel into two parts, of which the first is characterized by external control, the second by progressive self-determination. The interpretation columns are inserted into the primary text. They can also be read as a continuum. The reasons for the necessary chapter changes are also outlined.

Arrangement of the novel chapters

The arrangement of the chapters of the novel has been discussed since it was first published and repeatedly questioned. Kafka, who worked on the Trial between August 1914 and January 1915 , did not complete his work during his lifetime and therefore did not prepare it for publication. In a decree addressed to his friend Max Brod , he even asked him to destroy his writings after his death (→ Kafka's decree ).

The only text evidence is the manuscript recorded by Kafka, in which Kafka's numerous corrections can be found. After breaking off work on the work, from which he only published the short story Before the Law , he probably dissolved the notebooks in which he had written the text. As a result, the entire text was divided into 16 sections, partly broken up into individual chapters, partly into chapter sequences or only fragments of chapters. Between these sections he placed individual sheets on which he noted the contents of the series of sheets behind. These sixteen such severed bundles are usually as " convoluted called". The term “ chapter ”, on the other hand, implies a text and meaning unit deliberately determined by the author within a work, so this term does not correctly reflect the facts.

Due to the fragmentary nature of the text, different editions have been published, some of which differ greatly. The critical edition and the edition published by Brod assign the character of a completed work to the fragment by defining the order of the manuscript pages.

Brod had arranged the bundles into chapters for the first edition of the work. As a basis he used the bequeathed originals, which were stored encrypted in three envelopes with a cryptic system that could only be decrypted by its author and that interpreted the bread in its own way.

The arrangement of the chapters in The Trial is therefore always at risk of ideological appropriation of the writer Kafka, and thus every arrangement for a text edition of the work is already an interpretation.

Guillermo Sánchez Trujillo

Guillermo Sánchez Trujillo is in Crimen y castigo de Franz Kafka, anatomía de El Proceso ( "Franz Kafka's Crime and Punishment, Anatomy of The Process") based on a finding of similarities between Kafka's Process and Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment hypothesized that Kafka the novel by the Russian writer Dostoyevsky and others of his stories in the manner of a palimpsest had used the process to write and others of his narrative works. Trujillo refers to the study by the writer Christoph D. Brumme, Schuld und Innschuld des Josef K. , published in akzente 5/1998. According to Brumme, Josef K. is the innocent Raskolnikov, who is persecuted with the same means as a murderer. Between the characters and scenes of the two novels, there should be 70 places similar. Trujillo argues that the arrangement of the chapters can also be objectively determined in Dostoevsky's novel because of the similarities. Guillermo Sánchez Trujillo in Medellín (Colombia) published a critical edition of the novel with this new arrangement in 2015. Trujillo comes to the following arrangement:

- arrest

- Conversation with Mrs. Grubach / then Miss Bürstner

- B's girlfriend

- First investigation

- In the empty meeting room / The student / The offices

- The beater

- To Elsa

- Prosecutor

- The uncle / Leni

- Advocat / manufacturer / painter

- Merchant block / termination of the lawyer

- The House

- In the cathedral

- Fight with the deputy director

- A dream

- Drive to the mother

- The End

Structure according to the edition of Reclam Verlag (2006)

content

- arrest

- Conversation with Mrs. Grubach / then Miss Bürstner

- First investigation

- In the empty meeting room / The student / The offices

- The beater

- The uncle / Leni

- Lawyer / manufacturer / painter

- Merchant block / dismissal of the lawyer

- In the cathedral

- The End

Fragments

- B's girlfriend

- Prosecutor

- To Elsa

- Fight with the deputy director

- The House

- Drive to the mother

Structure according to the edition of the Suhrkamp Verlag (2000)

The process

- Arrest · Conversation with Mrs. Grubach · Then Miss Bürstner

- First investigation

- In the empty meeting room · The student · The offices

- Miss Bürstner's friend

- The beater

- The uncle Leni

- Lawyer · Manufacturer · Painter

- Kaufmann Block · Notice of Attorney

- In the cathedral

- The End

attachment

The unfinished chapters

- To Elsa

- Trip to mother (end deleted)

- Public prosecutor (as a direct attachment to chapter 7)

- The house (painted end)

- Fight with the deputy director (mostly deleted)

- A fragment ("When they stepped out of the theater ...")

reception

- Max Brod writes in the afterword of the first edition of 1925 in relation to the Trial that “hardly [a reader] will feel his gap” if he does not know that Kafka left his work unfinished. The editor goes on to say that the chapters completed in his opinion allowed "both the meaning and the form of the work to emerge with the most illuminating clarity". In addition, in the afterword to Kafka's work, Brod always speaks of a “novel” and not of a fragment. This shows that he is of the opinion that nothing essential is missing from the work. This is the impression that his edition conveys to the readers. The image of an almost completed work, which was available to the readership of that time and which still prevails among many readers today, justified and partly justifies the success and admiration for the trial .

- On November 17, 1988, the original manuscript of the work was auctioned in London for one million pounds by the German Literature Archives in Marbach. This was the highest price ever paid at auction for a single manuscript. The money came from the federal government and the state of Baden-Württemberg. The manuscript is on display in the Museum of Modern Literature .

- Peter-André Alt (p. 391/419): K's story is the dream of guilt - a dream of fear that takes place in the imaginary spaces of a strange legal order as a reflection of mental states. If K. also dies “like a dog”, the shame remains that only people can feel. But it is known - as a consequence of the expulsion from paradise - the result of knowledge about the difference between good and bad. What distinguishes humans from animals also forms the stigma of guilt.

- Reiner Stach (p. 537): Kafka's trial is a monster. Nothing is normal here, nothing is easy. Whether one deals with the genesis, the manuscript, the form, the material content or the interpretation of the novel: The finding always remains the same: darkness wherever you look.

Whereabouts of the manuscript

Before his death, Kafka had asked his friend Max Brod to destroy most of his manuscripts. Brod resisted this will, however, and saw to it that many of Kafka's writings were published posthumously. In 1939, shortly before the German troops marched into Prague, Brod managed to save the manuscripts to Palestine . In 1945 he gave them to his secretary Ilse Ester Hoffe , as he noted in writing: "Dear Ester, In 1945 I gave you all of Kafka's manuscripts and letters that belong to me."

Hope offered some of these manuscripts, including the manuscript of The Trial , through the London auction house Sotheby’s . In 1988, Heribert Tenschert bought it for 3.5 million DM (1 million pounds) . It can now be seen in the permanent exhibition of the Modern Literature Museum in Marbach.

Adaptations

Radio play and audio book adaptations

-

The Process (2010): Radio play version of the Bavarian Radio Radio play and media art , directed by Klaus Buhlert . Released in 16 parts on 17 unnumbered CDs. Based critical Historical-on the text output by Roland Reuss and Peter Staengle in publishing Stroemfeld / Red Star in 1997.

Each of the 16 chapters of Kafka was not published on a separate CD with details of the chapter title, without consecutive numbering of the chapters or CDs (a chapter due the length on two CDs). Since Kafka's chapter arrangement is unclear, the listener should be able to create his own order. The radio and podcast versions were also broadcast in a different order than the generally known order (see above). Kafka's deletions known from the facsimiles were also recorded for the radio play . Speakers are Rufus Beck , Samuel Finzi , Corinna Harfouch , Jürgen Holtz , Milan Peschel , Jeanette Spassova , Thomas Thieme and Manfred Zapatka .

CD edition: Der Hörverlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-86717-690-3 . - The process: Sven Regener reads Franz Kafka , unabridged reading, Roof Music, Bochum 2016, ISBN 978-386-484-399-0 .

Theater adaptations

- The writer and director Steven Berkoff adapted some of Kafka's stories into plays. His version of the Trial premiered in London in 1970 and was published as a book in 1981. The first performance in Germany took place in 1976 at the Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus .

- At the suggestion of the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman , the writer Peter Weiss wrote a stage version of The Process in 1974 , which was closely based on Kafka's original. The trial was premiered simultaneously on May 28, 1975 at the Theater of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen under the direction of Helm Bindseils and at the United City Theaters in Krefeld and Mönchengladbach under Joachim Fontheim's direction.

- In addition, Peter Weiss developed the play The New Process in 1981 , in which he transferred Kafka's original to the present of multinational corporations and political power and surveillance apparatuses. The new trial premiered on March 12, 1982 at the Dramaten in Stockholm under the direction of Gunilla Palmstierna-Weiss and Peter Weiss. The German-language premiere was directed by Roberto Ciulli on March 25, 1983 at the Freie Volksbühne Berlin .

- Andreas Kriegenburg staged a widely acclaimed theatrical version at the Münchner Kammerspiele (premiere: September 25, 2008).

Film adaptations

- The Trial (1962) by Orson Welles

- Kafka (1991) by Steven Soderbergh (feature film that combines parts of Kafka's life with elements from The Trial , The Castle and other texts)

- The Trial (1993) by David Hugh Jones

- At the end of the corridor (1999) by Michael Muschner (short film)

- The Process (2015) by Cornelia Köhler (school film, DVD)

Comic adaptation

- Guido Crepax : Il processo di Franz Kafka, Piemme 1999

- Chantal Montellier and David Zane Mairowitz: The Trial. A graphic novel. London: SelfMadeHero 2008.

Musical adaptations

- Gottfried von Einem's opera The Trial (1953) is based on Kafka's fragment of the novel.

- Gunther Schuller's jazz opera The Visitation (1966) is a free adaptation of the material .

- The opera Proces Kafka (2005) by the Danish composer Poul Ruders combines scenes from Kafka's life with episodes from the novel ; the English libretto is by Paul Bentley

- The Scottish post-punk band Josef K named itself after the hero of the novel

- The Polish punk band Pidżama Porno released the song Józef K. on their album Bułgarskie Centrum in 2004 , in which they refer to the content of Kafka's piece.

- The book (with English title) can be seen on the cover of the album If You're Feeling Sinister by the British indie pop band Belle and Sebastian .

literature

expenditure

As can be read in the Editions section , it is important which edition you choose. Therefore, the listing is based on the different editions.

- Historical-critical edition of the manuscript:

Stroemfeld Verlag , 16 individually stapled design chapters in a slipcase together with Franz Kafka booklet 1 and CD-ROM, with 300 manuscript facsimiles: Der Process . Edited by Roland Reuss. Stroemfeld, Frankfurt / Main, Basel 1997, ISBN 3-87877-494-X - Reprint of the first edition (1925):

Stroemfeld Verlag, bound. ISBN 978-3-87877-500-3 - Critical Edition:

The Proceß . Edited by Malcolm Pasley. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 2002, bound ISBN 3-596-15700-5 - Edition of Eschweiler:

Franz Kafka: "The process" . Reorganized, supplemented and explained by Christian Eschweiler. Landpresse, Weilerswist 2009. ISBN 978-3-941037-40-3 . - Other editions:

- Structure, paperback ISBN 3-7466-1615-8 .

- dtv, paperback ISBN 3-423-02644-8 .

- Langenscheidt, paperback ISBN 3-580-63335-X .

- Probst, bound ISBN 3-935718-94-2 .

- Saur, hardcover ISBN 3-598-80009-6 .

- Schöningh, paperback ISBN 3-14-022362-5

- Suhrkamp: paperback - ISBN 3-518-39337-5 , BasisBibliothek - ISBN 3-518-18818-6 .

- Vitalis, hardcover ISBN 3-89919-052-1 .

- Volker Krischel Königs Explanations ISBN 3-8044-1796-5 .

- Anaconda, hardcover ISBN 3-938484-77-2 .

- Hamburger Reading Books Verlag, 201. Issue ISBN 978-3-87291-200-8 .

Secondary literature

- Peter-André Alt : Franz Kafka. The Eternal Son. A biography. 2nd edition, Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57535-8 .

- Manfred Engel : Franz Kafka: The Trial (1925) - Judgment day on the modern. In: Matthias Luserke-Jaqui / Monika Lippke (Hrsg.): German-language novels of classical modernism. Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-018960-5 , pp. 211-237.

- Manfred Engel: The trial. In: Manfred Engel, Bernd Auerochs (Hrsg.): Kafka manual. Life - work - effect. Metzler, Stuttgart, Weimar 2010, pp. 192-207. ISBN 978-3-476-02167-0 .

- Janko Ferk : Law is a "process". About Kafka's legal philosophy . Manz, Vienna 1999, ISBN 3-214-06528-9 (also dissertation at the University of Vienna 1998); 2nd edition, Edition Atelier, Vienna 2006, ISBN 978-3-902498-10-6 .

- Wilhelm Große: Reading key. Franz Kafka: The process. Reclam, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-15-015371-0 .

- Volker Krischel: Explanations to Franz Kafka: The Proceß. Text analysis and interpretation (vol. 417), Bange , Hollfeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-8044-1910-0 .

- Rainer von Kügelgen: “Not enough respect for the scriptures” or How to clear a disturbance: Kafka's parable “Before the Law” in Orson Welles' film “The Trial”. In: Osnabrücker Contributions to Language Theory 61, 2000, pp. 67-92, ISBN 3-924110-61-1 [1] .

- Rainer von Kügelgen: Definitions: Kafka's “Process” as reflected in the first sentence. 2001 [2] .

- Ekkehart Mittelberg : Franz Kafka: The trial. Lesson suggestions and master copies. Cornelsen, Berlin 2003, ISBN 978-3-464-61425-9 (= LiteraMedia series ).

- Manfred Mitter: Franz Kafka: The process, interpretation impulses . Merkur, Rinteln ISBN 978-3-8120-0853-2 (text booklet), ISBN 978-3-8120-2853-0 (CD-ROM).

- Reiner Stach : Kafka The Years of Decisions. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-16187-8 .

- Reiner Stach: Is that Kafka? (99 finds) . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2012, ISBN 978-3-596-19106-2 .

- Ralf Sudau: Franz Kafka: Short prose / stories. Klett, Stuttgart / Leipzig 2007, ISBN 978-3-12-922637-7 .

- Cerstin Urban: Franz Kafka: Erzählungen II. (King's explanations and materials, Bd. 344). Bange, Hollfeld 2004, ISBN 978-3-8044-1756-4 .

- Louis Begley : The vast world that I have in my head. About Franz Kafka (original title: The Tremendous World I Have Inside My Head, translated by Christa Krüger). Pantheon, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-570-55095-3 .

- Bettina von Jagow and Oliver Jahraus : Kafka manual. Life-work-effect. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-20852-6 .

Web links

Text of the novel fragment

- The process in the Gutenberg-DE project (text follows the Brod edition)

- The process at Zeno.org .

Interpretations

- Dieter Schrey: Franz Kafka, "The Process" - The self-portrayal of birth as death

- Uwe-Jürgen Ness: The doorkeeper legend as the key to understanding Kafka

- Christian Eschweiler: Kafka's “The Process” in a new light

- Karin Leich: Dominance and sexuality in Franz Kafka's novels "Der Proceß" and "Das Schloß" by Karin Leich, University of Marburg, 2003 (PDF file; 1.6 MB)

- Janko Ferk: Franz Kafka's “The Trial” and its relation to the Austrian Code of Criminal Procedure

Editions of the work

- Institute for Text Criticism Edition as part of the historically critical Franz Kafka edition

bibliography

- Complete bibliography on novels and secondary literature (PDF file; 435 kB)

Radio play adaptation

- The Process - 16-part version of Bayerischer Rundfunk, 2010 (based on Roland Reuss and Peter Staengle 1997 by Verlag Stroemfeld / Roter Stern)

Film adaptations

- The process (1962) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Kafka in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- The process (1993) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- At the end of the aisle in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Shinpan (2018) in the Internet Movie Database (English)

classes

- Teacher training-BW teaching projects German: The process

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alt p. 388

- ↑ King's Explanations Franz Kafka The Volker Krischel Proceß p. 31

- ↑ King's Explanations / Krischel p. 34

- ↑ http://www.kafka.org/picture/roland/9.jpg Original Kafka's handwriting of the cathedral scene, when arriving late

- ↑ K. is an hour too late to close after the bell tower clock has rung, but the narrator claims that he is on time (Reclam, p. 188, lines 13-15). Later, after K.'s clock, it is still 11 a.m., and there is talk that he is no longer obliged to wait (p. 192). In the edition of Schöningh ( Simply German “The Process” ), for example, the time was corrected: “[…] about ten o'clock to meet in the cathedral” (p. 198, line 10). "K. had arrived on time, it had just struck ten when he entered, but the Italian was not here yet ”(p. 200, lines 14f.)

- ↑ There is another prose piece from the context of the trial novel, namely A Dream , which was published in the Landarztband , in which a Josef K. appears. However, this prose piece was not included in the novel (Alt, p. 625).

- ↑ For examples see z. B. Krieschel pp. 108-110

- ↑ M. Müller / von Jagow p. 528

- ↑ Krieschel p. 111

- ↑ Peter-André Alt p. 389

- ↑ Louis Begley p. 297

- ↑ Cerstin Urban p. 43.

- ↑ Ralf Sudau p. 103

- ↑ von Jagow / Jahrhaus / Hiebel reference to Canetti: The other process. P. 458.

- ↑ von Jagow / Jahrhaus / Hiebel reference to Adorno: Notes on Kafka. P. 459.

- ↑ a b Claus Hebell: Legal theoretical and intellectual historical prerequisites for the work of Franz Kafka, analyzed on the novel “The Trial”. Dissertation, Munich, 1981, ISBN 978-3-631-43393-5 , ( online )

- ↑ Peter-André Alt, p. 417.

- ↑ von Jagow / Jahrhaus / Hiebel, p. 462.

- ↑ Peter-André Alt, p. 401 f.

- ↑ Krischel, p. 113.

- ^ Max Brod's biography of Franz Kafka. A biography (new edition 1974 entitled: About Franz Kafka )

- ↑ Reiner Stach / decisions p. 554

- ↑ Stach, is that Kafka? P. 163 f.

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk : Life as Literature - 80 years ago, Kafka's novel “The Trial” appeared on April 26, 2005

- ↑ See www.kafkaesk.de

- ↑ ARD ( Memento of the original from November 22, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Kafka - The Last Trial, November 20, 2016, 10:40 a.m., 51 min., From min. 26, accessed on November 21, 2016

- ^ Report in the FAZ about the new permanent exhibition.

- ↑ Berkoff, Steven. "The trial, Metamorphosis, In the penal colony. Three theater adaptions from Franz Kafka. ”Oxford: Amber Lane Press, 1981.

- ↑ Cornelia Köhler: The trial . Anne Roerkohl Documentary, Münster 2015, ISBN 978-3-942618-15-1 ( documentarfilm.com ).