The world collector

The World Collector is the second novel in print by Bulgarian- born author Ilija Trojanow , who is native to Kenya , South Africa , Germany , India and Austria and published in 2006 . The book was awarded the Leipzig Book Fair Prize in 2006 (Category: Fiction ) and was a finalist at the German Book Prize . His novel has fitted in with his existing works since Die Welt ist große und Rettung lurert everywhere (1996), by indirectly addressing the question of transcultural identity in the course of the discussion about the dominant culture and receiving it accordingly.

action

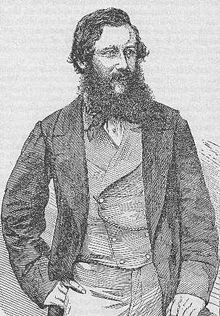

The novel traces major stages in the biography of Richard Francis Burton (1821–1890), who initially served as an official of the East India Company , and later became one of the first Europeans to make the pilgrimage to Mecca in the guise of an Indian Muslim . The third great station of his life was a great voyage of discovery to Central Africa in search of the sources of the Nile.

The plot is limited to three stages of his life over a period of sixteen years in India (career and love), Arabia (certainty of faith through the Hadj Bart) and East Africa (fame of exploration and annuity), which are each associated with special hopes and expectations .

In the first part, Burton goes to India at the age of 21 to lead a life that hardly any other European can imagine. He learns the national language, customs and traditions, and above all tries to understand the people who live there. Instead, he sometimes lives for weeks as one of them in the midst of the Indian population. Richard Francis Burton takes a local teacher, learns Hindi , Gujarati , Farsi and later Arabic . In the Brahmins Upanishe he learned Sanskrit and thus comes with the Kamasutra into contact, which he will later translate into English. Finally, he comes into closer contact with Islam , which in a sense creates the transition to the second part of the book. In order to be able to undertake a pilgrimage to Medina and Mecca, he embarked disguised and incognito as an Indian Muslim in 1853/1854 to Cairo , where he was generally accepted and, thanks to his talent for acting, soon settled as a doctor. Burton goes into his new home, so to speak, in order to be able to complete the pilgrimage enthusiastically and successfully. In the end, the question arises as to whether he has not also converted to Islam internally. The third part of the work describes Burton's life as an explorer at the side of his original friend, John Hanning Speke, in search of the sources of the Nile , both equally driven by the explorer's thirst for knowledge. On February 13, 1858, they were the first Europeans to discover Lake Tanganyika , which Burton believed to be the source of the Nile.

Burton's hopes and expectations are necessarily shattered in the end, despite or because of his brilliant talents, and at the same time he alienates himself from people. B. his Indian lover Kundalini, von Speke or his own wife Isabel, more and more. This makes the historical Briton a paradigmatic, ie eminently literary figure. Of course, the choice of this fascinating personality is a stroke of luck, because the author only needed to bend incidental, authenticated facts in order to achieve his goal: Ultimately, Burton always has to fail in himself and with him the occidental outlook that he represents.

This is also made clear by the framework, which outlines the consequences of his death in Trieste rather than dying : his notes go up in flames and a bishop appoints him an honorary Catholic for the sake of convenience. Finally, the eye falls on his Persian calligraphy : This too will pass.

The novel is not limited to one narrative perspective , as Burton's servants or other contemporary witnesses such as his travel companion also have their say.

Narrative method and genre allocation

From a narrative point of view , sections with Burton's reflections or documents alternate with other people's reports about him from their very own point of view. In India this is done in a hierarchical perspective break (servant, Lahiya), in Arabia it is fanned out (the witnesses and officials from Mecca in the course of the interrogation), in Africa it is narrowed to the only seemingly naive narration of the Führer. From India to Africa, the knowledge of others about Burton decreases, but at the same time the openness of the reporters increases. Such counter-rotation, shown here by way of example, can be regarded as a structural principle that sometimes culminates in paradoxes: The Indian writer reaches the truth through his imagination, and the African leader still best understands the essence of the Englishman, although he never closes became his confidante and does not want to understand him at all. Overall, this creates a subtle tension, but there is no psychological novel because the reader himself is referred to his analytical skills, and certainly not an adventure novel, because external action takes a back seat, as even particularly exciting guaranteed events are suppressed. But not a historical novel either, facts have to give way too much to the will of art. Above all, the author never misuses his character as a mouthpiece, and the real genre tells authorial , not personal. It is best to classify the work as a large parable about the failure of delusional, self-determined life plans.

background

The author himself describes his first contact with Richard Francis Burton's biography on his 10th birthday, which motivated him to write this work: “I'm sitting at a waterhole in the Tsavo National Park in Kenya and leafing through an illustrated volume about the famous explorers of Africa, that my parents gave me. In the magnificent book they all appear, the European heroes who set out to wipe the unknown from the face of the earth, from Vasko da Gama to Henry Morton Stanley . None of the illustrations fascinates me more than the colored engraving of a man dressed in Arabic with wild features and stern eyes. How strange: according to the caption, this man (..) was neither a slave trader nor a sultan , but a Briton. He was the first European to penetrate the interior of East Africa in search of the sources of the Nile, and as the only one of all the explorers in my book he looks like a local. The adventure of disguise excites and disturbs me more than the risk of the journey. I memorize this strange man's name: Richard Francis Burton. A good twenty years later I'm moving to Bombay, India, because I've decided to write a novel about Burton, or rather about the (im) possibility of living abroad ”.

For the research , the author decided to live in Bombay and Baroda for a long time in order to familiarize himself with the customs and traditions there like Burton once did. He also crossed Tanzania on foot with as little luggage as possible , in order to be able to “feel the slowness of traveling back then”. He spent a year in Bombay preparing for the Hajj, the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina , by teaching English to young Islamic legal scholars, who in turn taught him the Koran . Together with a group of Indian pilgrims he made the trip in January 2003.

criticism

In the reasoning of the jury, Martin Lüdke ( Südwestrundfunk ) Franziska Augstein ( Süddeutsche Zeitung ), Richard Kämmerlings ( Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung ), Andrea Köhler ( Neue Zürcher Zeitung ), Sigrid Löffler ( Literatures ), Norbert Miller ( Technical University Berlin ), Klaus Reichelt ( Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk ) and other experts and literary critics belonged to the Leipzig Book Fair Prize, the conclusion of the work was described as follows: “Ilija Trojanow's novel about the British spy, diplomat and explorer Richard Francis Burton is an exciting and profound approach to one of the most dazzling figures of the nineteenth century. With oriental, sensual love of tales and great vividness, the novel tells of the charm and adventure of the foreign and thus reflects the pressing questions of our present in a fascinating historical figure ”.

Trojanow's Weltensammler, which was presented with media coverage in hot off the press , among other things , was confirmed by the critics to be a great German-language novel again after a long time, because it shows itself to be well structured down to the last detail, which, of course, only reveals itself to be read more closely, offers a rich and poetic language and depth of content.

Although Trojanow is ingeniously connected to the formerly great European narrative tradition, especially German and Slavic authors, no direct role models can be found, but he could be seen as a completely different descendant of Joseph Conrad , the community only consisting in the fact that both writers did not come from their roots Write language, but teach fear to their native-speaker contemporaries, like to choose distant locations (admittedly with a different intention) and speak of the loneliness of the individual.

Katharina Granzin saw it in the taz more differentiated: “What interests Trojanow is life and the search for identity between cultures; and the life of Richard Burton provides an excellent basis for playing through this theme in variations. Trojanow's rest of the work - mostly literary reports as well as another novel - revolves around this vast field again and again on various paths. (...) A disappointing anticlimax: after that furious first part, which questioned its main character so emphatically, at the end it seems as if Trojanow had forgotten that he might still have an account to be taken with Burton. What began as a novel of ideas ends in the jungle report. But it's always beautifully told. (...) It is not possible to really look inside the figure if you want to let it keep its secret. Trojanow's world collector is reminiscent of Hari Kunzru's novel The Changes of Pran Nath . "

“You could read the book as an adventure novel, but it's also a lot more. In many pictures and impressions you get to know India, smells rise, the hardships of the journey become noticeable, Trojanow lets the reader participate sensually. And you get an impression of the different cultures and religions, peppered with criticism and skepticism towards Europeans, who mostly - unlike Burton - do not look very closely and therefore do not understand. The novel is expanded by changing the narrative perspective. In each part, alternating chapters, his servant, a travel companion or other witnesses have their say, adding to Burton's perspective or introducing completely new aspects. The tremendous energy and drive of Burton amaze, his sometimes eccentric and deviant behavior animate reading. And that makes up a good part of the charm of the book, in addition to the immersion in foreign worlds and the differentiated views both of the plot and when looking at cultures ”.

The literary criticism attested the work as a biography, like all global or transcultural résumés, a "great radiance", which can be seen in the sales success alone, but also pointed out that with all the exoticism and the fascination for apparently unknown phenomena, it was questionable , "To what extent such an attitude actually contributes to the development of an intercultural identity".

Reception and interpretation

The world collector not only encouraged literary scholars to investigate, but also linguists and sociologists. Michaela Haberkorn put a quote from Trojanow right at the beginning of her comparative essay on the migration discussion “Drift Ice” and “World Collectors”. Concepts of nomadic identity in the novels by Libuše Moníková and Ilija Trojanov : “We are all guests. We are all hikers. Be one of us ”. Because in intercultural or transcultural literature, intermediate worlds and moments of transition arise in the area of tension between cultural ambivalences and the mutual interpretation of reality. Literary texts are of interest because in them "the linguistic or cultural hybridization, the interplay of stereotyping processes and resistance as well as the deconstruction of cultural classifications take place". Since Trojanov takes a public position on current social and political developments or questions about the dominant culture or standardized cultural standards , his demand for a new way of thinking about society must be given special consideration.

Accordingly, Trojanow himself formulated it before the publication of this book: “The nomadic journey through an eternally changing definition of one's own identity is in blatant contradiction to the demand for assimilation , through which the nation-state seeks to protect its ostensibly uniform body from foreign influences. In vain, because while the literature of self-determined roots thrives, the nation-state is dying, at least as an ideological model. In all social spheres there is plurality; the Internet as an organizational form has more promising future than the nation state. (...) With the nation-state, thinking dissolves into binary oppositional patterns ”.

In the debate about the nationally oriented concepts of identity, according to Trojanow's view, which is shared by a number of sociologists and linguists, it is precisely the concept of nationality that should be questioned, as this is changing in modern societies. Artificial categories such as mother tongue , home country or even culture of origin influence it less and less.

Trojanow himself sees it concretely from his own experience:

- “One of the great misunderstandings in the prejudiced debate about identity and integration , about origin and homeland , is the assumption that the past shapes a person's sense of belonging. Of course it is important to know where you come from, but just as important is the question of where you want to go. Every person who has emigrated, every refugee or exile is forced to ask this question at some point, and the man of letters [!] Lives in it as long as he is creative ”.

This raises the question of “the chosen or ascribed character of identity” and its changeable character. In the literature itself there are various examples in which the changing identity formation in postmodern societies is discussed. With such patchwork identities, there is no stable self-ascription of identity features, but rather the “manufacturing process” of an identity is the focus of interest.

The first thing that changes is the language perception: "Koreans or Brazilians may not even notice that" Der Weltensammler "was originally written in German."

Trojanow's previous literary works fit into the pattern just as much as the rumors about his alleged conversion to Islam coincide with Burton's biography. Later he characterized a “literature of linguistic and cultural symbioses in the German language” which could create its own aesthetics and gain the narrative perspective from its “position of foreignness”. In later works Trojanow described the globalized society with the help of the metaphor of Indra's network. He sees the confluence of different cultures as the basis of every progress in civilization. "In his literary texts Trojanow shapes these spheres of confluence and mixing from the point of view of the individuals who wander through and live through them ".

In Der Weltensammler , Burton's figure ultimately serves to illustrate that cultural contact brings about an internal and external change in the protagonist: “The situation between the colonized and the colonized is characterized by an inequality of power as well as generalizations and ascriptions that prevent a differentiated understanding of culture on both sides. In approaching India, its people and cultures, Burton treads two paths, on the one hand that of disguise, masquerade and mimicry , and on the other hand that of learning and spiritual renewal ”. In the person of the factotum Sidi Mubarak Bombay , from whose perspective the third part of the book is told, one recognizes equally cultural parallels between the changing identities to Burton, but in contrast to these he has internalized his change of identity and not as a survival strategy or mask cultivated. In the person of linguistically limited Speke who can tell the Africans against only in English, is also still finds an antipode to Burton, who thanks to his Hindi, Arabic and later Kiswahili -Knowledge can far better inform its foreign environment.

Because what fascinated Troyonov most was “Burton's endeavors to penetrate the foreign, to recognize cultural differences, to understand, to name and to overcome them - be it through masquerade, be it through transformation. His motto was: Omne Solum Forte Patria: Every place is home to the strong. Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, questions about our cultural identity are becoming increasingly urgent. A growing number of people live in those hybrid worlds and benefit from the confluences to which Burton exposed himself. Burton's interest in Islam and the Arab world is particularly contemporary. Burton knew the Middle East better than almost any other European, he mastered classical Arabic as well as everyday languages. The circumstances of his life, his many years of confrontation and friendship with Arabs and other Muslims, and his knowledge of their ways of thinking, including local differences, gave him an insight that was not always free of Victorian prejudices, but always knowledgeable and refreshingly original ”.

The author and his novel were also received with interest in English-speaking countries, but there they primarily revolved around the biographical reference, the English and German reception also in the well-known adaptation by Karl May and the eternal question of the pretense of the pilgrimage.

Trojanow's portrayal of Burton's religious empathy was also given detailed consideration by religious educators, rich in citations.

Edits

The stage version of Der Weltensammler , edited by Johannes Ender, premiered on August 21, 2016 at the Dresden State Theater in the Schlosstheater under the direction of Ender. The actors were Jasper Diedrichsen , Katharina Lütten and Christian Clauß.

expenditure

- Ilija Trojanow: The world collector. Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-446-20652-3 . (bound, 477 pages)

- Ilija Trojanow: The world collector. dtv, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-13581-8 .

- Ilija Trojanow: The world collector. Voiced by Frank Arnold . Audiobuch Verlag, Freiburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-89964-204-9 . (7 CD, 496 minutes)

- Ilija Trojanow: nomad on four continents. Frankfurt 2007. (In this work Trojanow describes his own travels in the footsteps of the “world sampler” Richard Burton.)

literature

- Jana Domdey: Intertextual Afrikanissimo: Postcolonial storytelling in the East Africa chapter of Ilija Trojanow's “Der Weltensammler”. In: Acta Germanica 2009, pp. 45-66.

- Manfred Durzak (ed.): Images of India in German literature. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2011, ISBN 978-3-631-61437-2 .

- Matthias Rath: About the “(im) possibility to live in a foreign country”. Cultural assimilation as disintegration using the example of Ilija Trojanow's novel “Der Weltensammler”. In: arcadia - International Journal for Literary Studies , 45, 2011, issue 2, pp. 446–464.

- Gregor Streim: Different Worlds or Different Worlds? On the historical perspective of globalization in Ilija Trojanow's novel “Der Weltensammler”. In: Wilhelm Amann, Georg Mein and Rolf Parr (eds.): Globalization and contemporary literature: constellations, concepts, perspectives. Heidelberg 2010, pp. 73-89.

Web links

- Issues of The World Collector by Ilija Trojanow in LibraryThing

- Review notes on Der Weltensammler at perlentaucher.de

- http://www.literatur.ilruff.de.vu under V. Standpunkte: Trojanow offers a detailed study

- World collectors and tin drummers: A conversation with Günter Grass and Ilija Trojanow (PDF; 62 kB)

- Hilal Sezgin: As if two blind people had shared a woman. Everything, just not an adventure novel: Ilija Trojanow follows the hardly flammable “world collector” Richard Francis Burton . In: Frankfurter Rundschau , March 15, 2006

- Mannerist language strategies of the author (PDF; 76 kB)

- literaturcafe.de - Podcast # 10 - Ilija Trojanow: Der Weltensammler, October 6, 2006 (7 MB; MP3)

- The ethnological salon 2007. Series of events in the State Museum of Ethnology, Munich (with Trojanow's participation)

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.mdr.de/2477317.html#absatz4 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Antje Gunsenheimer (ed.), Limits. Differences. Transitions. Areas of tension in inter- and transcultural communication , Bielefeld: transcript 2007, ISBN 978-3-89942-794-3

- ↑ Bassam Tibi, Leitkultur as Consensus of Values - Balance of a Unsuccessful German Debate, In: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschehen (The Parliament), B 1–2 / 2001, pp. 23–26

- ↑ http://www.ilija-trojanow.de/roman.cfm

- ↑ http://www.ilija-trojanow.de/weltensammler.cfm

- ↑ http://www.ilija-trojanow.de/recherche.cfm

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento from October 20, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento from February 13, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Summary of several reviews by the NZZ, SZ and FAZ ( Memento from April 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Further press comments in the after quote ( Memento from April 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Katharina Granzin: The jewelry of female monkeys. taz.de, March 25, 2006.

- ↑ http://www.lesemond.de/titel/trojanow_weltensammler.html

- ↑ Also in demand as an international lecture topic, e.g. B. Yvonne Delhey (Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, Netherlands): Ilija Trojanow and 'self fashioning'

- ↑ Alone 110,000 copies in the year of publication according to Der Spiegel 52/2006

- ↑ Hannes Schweiger, Deborah Holmes: National borders and their biographical transgressions. In: Bernhard Fetz: The biography. To lay the foundation of their theory. Walter De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, p. 406 a. 407

- ^ Libuše Moníková : Drift ice . Hanser, Munich 1992.

- ↑ Michaela Haberkorn: "Treibeis" and "Weltensammler". Concepts of nomadic identity in the novels of Libuše Moníková and Ilija Trojanov . In: Helmut Schmitz (Ed.): From national to international literature: Transcultural German-language literature and culture in the age of global migration . Rodopi, Amsterdam 2009, pp. 243–262, here p. 243.

- ^ Ilija Trojanov: The collector of the world . Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich / Vienna 2006, p. 111.

- ↑ Cf. Martina Ölke: Ilija Trojanow's successful novel “Der Weltensammler” . In: Petra Meurer, Martina Ölke, Sabine Wilmes (eds.): Intercultural learning. With articles on German and DaF lessons, on images of 'migrants' in the media and on texts by Özdamar, Trojanow and Zaimoglu. Aisthesis Verlag, Bielefeld 2009, ISBN 978-3-89528-748-0 .

- ^ Michaela Haberkorn: Drift ice and collectors of the world. Concepts of nomadic identity in the novels of Libuše Moníková and Ilija Trojanov . In: Helmut Schmitz (Ed.): From national to international literature: Transcultural German-language literature and culture in the age of global migration . Rodopi, Amsterdam 2009, pp. 243–262, here p. 246.

- ^ Jürgen Nowak: Leitkultur and Parallel Society. Arguments against a German myth. Brandes & Apsel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2006.

- ↑ Ilija Trojanow: Döner in Walhalla or What traces the guest who is no longer leaves behind. In: Ilija Trojanow (Ed.): Döner in Walhalla. Texts from other German literature. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2000, p. 10.

- ↑ See Stuart Hall : Cultural Identity and Globalization. In: Karl H. Hörning, Rainer Winter (Ed.): Unruly Cultures Culturell Studies as a Challenge. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1999, pp. 393-441, here p. 407.

- ^ Ilija Trojanow: Doner kebab in Walhalla. P. 10.

- ↑ Peter Wagner: Fixed positions. Observations on the social science discussion about identity . In: Aleida Assmann, Heidrun Friese (Ed.): Identities. Memory, history, identity. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1998, pp. 44-72, especially p. 59.

- ^ Marion Gymnich: Individual identity and memory from the point of view of identity theory and memory research and as an object of literary staging . In: Astrid Erll, Marion Gymnich, Ansgar Nünning (Hrsg.): Literature - Memory - Identity. Theory concepts and case studies. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, Trier 2003, pp. 29–48, here p. 33. (= Studies on English Literature and Cultural Studies. Volume 11.)

- ↑ Wolfgang Bader, head of the Goethe Institute in Sao Paulo, on literary reception in Brazil. 2008

- ^ Ilija Trojanow: The rapture gives birth to monsters. Interview with Ilija Trojanow. In: Özkan Ezli: Against cultural pressure: Migration, culturalization and world literature. transscript, Bielefeld 2008, p. 253ff, here p. 254.

- ↑ On the inner shores of India. A journey along the Ganges. Munich 2003.

- ↑ To the holy sources of Islam. Munich 2004.

- ↑ Cf. Ilja Trojanow has converted to Islam and has written a moving book about it. In: taz. Nov 27, 2004.

- ↑ Drawing on knowledge of the world: Ilija Trojanow in conversation. on: standard.at April 11, 2007.

- ↑ On Indra's network : The holographic world model between science and vision ( Memento from September 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The fight is canceled. Cultures don't fight each other - they flow together . (with Ranjit Hoskoté ). Munich 2007.

- ↑ The Unleashed Globe. Munich 2008.

- ↑ Michaela Haberkorn: "Treibeis" and "Weltensammler". Concepts of nomadic identity in the novels of Libuše Moníková and Ilija Trojanov . In: Helmut Schmitz (Ed.): From national to international literature: Transcultural German-language literature and culture in the age of global migration . Rodopi, Amsterdam 2009, pp. 243–262, here p. 253.

- ↑ Cf. Ilija Trojanow: The world is big and salvation lurks everywhere. Carl Hanser, Vienna 1996.

- ↑ Michaela Haberkorn: "Treibeis" and "Weltensammler". Concepts of nomadic identity in the novels of Libuše Moníková and Ilija Trojanov . In: Helmut Schmitz (Ed.): From national to international literature: Transcultural German-language literature and culture in the age of global migration . Rodopi, Amsterdam 2009, pp. 243–262, here p. 257.

- ↑ The World Collector: The Figure.

- ^ Penka Angelova: The Other Road. On the Bulgarian Topos in the Work of Three Writers Awarded the Adelbert von Chamisso Prize. In: Elka Agoston-Nikolova: Shoreless bridges: south east European writing in diaspora. Rodopi, Amsterdam 2010, pp. 84f.

- ↑ Katharina Gerstenberger, Patricia Herminghouse: German literature in a new century: trends, traditions, transitions. Berghahn Books, New York 2008, p. 11.

- ↑ Overview in: Christopher Ondaaje: Sindh Revisited: Journey in the Footsteps of Sir Richard Francis Burton, 1842-49. The India Years. HarperCollins, London 1996.

- ↑ Dane Kennedy: A Highly Civilized Man. Richard Burton and the Victorian World . Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 2005, pp. 248-273.

- ^ Karl Rolf Seufert: The Towers of Mecca. Richard Francis Burton's adventurous journey to Medina and Mecca . Herder, Freiburg 1963.

- ↑ on the influence on literature for young people: Gudrun Harrer: Morgenländer im Kopf. How the classic children's book “Hatschi Bratschi”, travel books and fairy tales have shaped ideas about the Orient . . In: The Standard . June 13, 2008.

- ↑ Karl May: Through the desert. Travel narration. Collected Works. Vol. 1. Karl-May-Verlag, Bamberg / Radebeul 2003. 1st edition 1892.

- ↑ Julian Preece: Faking the Hadj? Richard Burton Slips between the Lines in Ilija Trojanow's Der Weltensammler. In: Julian Preece, Frank Finlay, Sinead Crowe (Hrsg.): Religion in contemporary Germany: doubters, believers, seekers in literature and film. Peter Lang Verlag, Bern / Oxford 2010, p. 21ff. (= Leeds-Swansea colloquia on contemporary German literature, Vol. 2)

- ↑ Joachim Czech: On the treatment of non-Christian religions in religious instruction in vocational schools. An experience report. In: Jürgen Court: Ways and Worlds of Religions: Research and Mediation. Festschrift for Udo Tworuschka. Verlag Otto Lembeck, Frankfurt am Main 2009, pp. 63-78.

- ↑ The collector of the world. (No longer available online.) Www.staatsschauspiel-dresden.de, archived from the original on August 26, 2016 ; Retrieved August 26, 2016 .

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento from May 16, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Georg Patzer: Several lives. Ilija Trojanow tells in a book how he wrote the book about Richard Burton. In: Literaturkritik.de, August 8, 2007