Burke and Wills expedition

The Burke and Wills expedition (originally Victorian Exploring Expedition , German Victorian reconnaissance expedition ) was in the years 1860 and 1861 on behalf of the Government of Victoria conducted expedition , in Australia to the west of 143 degrees longitude was crossed from south to north. It led from the city of Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria about 3250 kilometers away and was under the direction of Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills. Seven participants died during the expedition, Burke and Wills were killed on the return trip. Only John King completed the entire expedition and returned to Melbourne.

The expedition was the best-equipped expedition in Australian history and received a lot of attention, but it failed due to a chain of unfortunate circumstances and also due to the poor leadership skills of Burke. The inexperienced leader dismissed numerous qualified participants on the way and could not handle the camels he was carrying. Furthermore, the wagons and animals were too heavily loaded; equipment and supplies were left behind several times. Because of the competition with John McDouall Stuart , who was also leading an expedition with the same goal from Adelaide , Burke was rushed and left no time for the scientific work that should be the focus of an expedition. Therefore, the expedition itself contributed almost no new knowledge about the nature of the Australian hinterland. The search parties sent from various parts of the country to rescue Burke and Wills played a more important role in the exploration.

After their death, Burke and Wills became heroes despite their failure. They were granted a state funeral in Melbourne and monuments were dedicated. But when the background of her death gradually became known, the enthusiasm subsided.

prehistory

The Burke and Wills expedition marks the end of a series of expeditions to explore the Australian hinterland since the early 19th century. In search of fertile landscapes and grazing areas for the herds of sheep, researchers gradually increased their knowledge of Australia beyond the Blue Mountains . The earliest expeditions, such as John Oxley's in 1818, explored the Murray-Darling river system but did not know it was a system and therefore could not answer the question of where all the rivers flow to. So various explanations came into question: An inland sea was possible that would be nourished by the rivers of the Great Dividing Range . Oxley's conclusion that the hinterland was an impassable bog was also plausible after each of his attempts to follow the rivers ended up in the swamp. Only Charles Sturt was able to largely clarify the question of the mouth of the rivers in 1828 with the discovery of the Darling and 1828–1830 with the discovery of the river system, but he only followed the Murray (whose tributary the Darling is) to Lake Alexandria and therefore did not find it found that the Murray drains into the sea. Gippsland , the area around what is now Melbourne, was explored in 1836 and 1839 by Thomas Livingstone Mitchell and Angus McMillan (1810-1865). From the mid-1840s, advances were also made in what is now Queensland .

In Victoria there was little public interest in an expedition. After gold was discovered there in 1851, a gold rush increasingly attracted immigrants to the country. The colony of Victoria became very prosperous and Melbourne quickly grew to become the largest city in Australia. The upswing lasted 40 years and led into the age known as “marvelous Melbourne” (roughly: “wonderful Melbourne”). The influx of educated immigrants from England, Ireland and Germany resulted in the construction of numerous schools, churches, learned societies , libraries and art exhibitions.

As a result, the equipment for the expedition was primarily a political decision: Rich Melbourne wanted to demonstrate its will to play a leading role in building the Australian state in the future. These efforts were driven by the influential Messrs William Stawell and Ferdinand von Mueller , who advocated it in the Philosophical Institute of Victoria founded in 1854 (since 1859 the Royal Society of Victoria ). In 1857 the Philosophical Institute set up an exploratory commission to investigate the feasibility of an inland expedition. Originally the goal was to cross the continent in an east-west direction. The plan was changed to a south-north crossing after Augustus Gregory , an explorer of Northern Australia, considered the project to be hopeless. Burke and Wills were in competition with John McDouall Stuart , who was to cross the continent on behalf of the government of South Australia . For the people of Adelaide , exploration of the continent was of great importance, as they relied on the development of fertile pastureland.

Preparations

| Surname | job |

|---|---|

| Wilhelm Blandowski | Zoologist, explorer of Australia |

| John Bleasdale | Clergyman, chemist and geologist |

| Francis Cadell | Explorer of Australia |

| Andrew Clarke | former soldier, politician |

| Richard Eades | Mayor of Melbourne |

| Clement Hodgkinson | Naturalist |

| John Macadam | Chemist |

| Frederick McCoy | paleontologist |

| Ferdinand von Mueller | botanist |

| Francis Murphy | Speaker of Parliament |

| Georg von Neumayer | Polar explorer |

| Alfred Selwyn | Government Geologist |

| William Foster Stawell | Chief Justice of Victoria |

| Edward Wilson | Editor of The Argus |

Exploration Committee

The scouting committee initially struggled to get money because of the low public interest in Victoria. It wasn't until 1860 that enough money was available to put the expedition together.

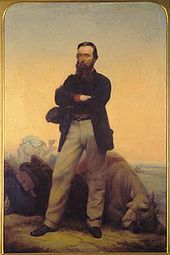

The exploration committee put the leadership of the Victorian Exploring Expedition out to tender. Only two members of the committee, Ferdinand von Mueller and Wilhelm Blandowski , had any experience with such exploration companies. However, they were always outvoted because parliamentary groups had formed within the committee. Several people were considered for the leadership position. Robert O'Hara Burke was recommended after a vote by the committee as chairman, George Landells as deputy, and William John Wills as surveyor, navigator and second deputy. Burke had no experience with such expeditions; apparently the committee overestimated him because of his self-assured demeanor. Born in Ireland, Burke was a former officer in the Austrian army and later a police officer. He had practically no skills in the art of survival . Wills was more likely to get by in the wilderness. It was Burke's leadership that is seen as the main reason for failure.

Participants in the expedition

A total of 29 people took part in the expedition. The original team of nineteen consisted of five British , six Irish , four Indian sepoys , three Germans and one American . Of the 29, six were officers in management positions, 19 assistants and four sepoys to look after the camels. The table below shows only participants who have not been dismissed and the leaders:

| Surname | position | group | Hired | Whereabouts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robert O'Hara Burke | ladder | Carpentaria | original crew | † June / July 1861, Cooper Creek |

| George Landells | ladder | Menindee | original crew | left expedition on October 14, 1860 |

| William John Wills | land surveyor | Carpentaria | original crew | † June / July 1861, Cooper Creek |

| Ludwig Becker | Draftsman, naturalist | Menindee | original crew | † April 29, 1861, Koorliatto waterhole |

| Hermann Beckler | Doctor, botanist | Menindee | original crew | Resigned in Menindee between October 14 and 21, 1860 |

| William Wright | ladder | Menindee | original crew | return |

| William Brahé | assistant | Cooper Creek | original crew | return |

| Thomas Mc Donough | assistant | Cooper Creek | original crew | return |

| William Patten | assistant | Cooper Creek | original crew | † June 5, 1861, Rat Point Camp after falling from his horse |

| John King | assistant | Carpentaria | original crew | was found by Alfred Howitt's rescue team on October 18, 1861 |

| Charles Gray | assistant | Carpentaria | 6-10 September 1860 in Swan Hill | † April 17, 1861 in Polygonum Swamp |

| William Purcell | assistant | Menindee | January 26, 1861 in Menindee | † April 23, 1861 at the Koorliatto waterhole, Bulloo River |

| John Smith | assistant | Menindee | January 26, 1861 in Menindee | return |

| Charles Stone | assistant | Menindee | January 26, 1861 in Menindee | † April 22, 1861 at the Koorliatto waterhole, Bulloo River |

| Dost Mahomet | Sepoy | Cooper Creek | original crew | later part of Howitt's rescue team |

| Belooch | Sepoy | Menindee | original crew | later part of Howitt's rescue team |

13 men were released en route and are therefore not included in the above list. Owen Cowen and Henry Creber were released in Melbourne on the day of departure and the day before departure for drunkenness and a third, Robert Fletcher, for "incompetence" in defending Creber. They were replaced by James McIlwaine, Jame Lane and Brooks, who, however, were also kicked out a few weeks later in Swan Hill and Balranald, together with Charles Ferguson, Patrick Langan and John Polongeaux (the latter was hired on August 26, 1860 in Mia). Another member of the original crew, John Drakeford, was finally released on October 14, 1860 in Menindee .

Three more people left the expedition: Robert Bowman resigned on September 18, 1860, 14 days after his recruitment. Of the four Indian sepoys, two dropped out prematurely: As a Hindu, Samla was not allowed to eat the food rations for religious reasons and therefore resigned on August 22, 1860. Esau Khan had to retire between September 6th and 10th due to illness.

equipment

The expedition was very extensively equipped, the total weight of the equipment should have been a good 20 tons and cost almost £ 5,000, the total cost of the expedition was £ 12,000, half of which was borne by the government. It was provided with food for two years, as well as lemon juice for the men and around 270 liters of rum for the camels to ward off scurvy . Landells wanted the rum to strengthen tired and weakened camels, according to another source it was supposed to protect against scurvy.

Instead of bringing cattle to be slaughtered during the trip, the committee decided to use dried meat instead. The extra weight required three additional wagons, which slowed the expedition considerably.

There were also some weapons and ammunition in the luggage, but also items such as a table, rockets and a Chinese gong. 23 horses, six wagons and 26 dromedaries were provided to transport this crowd .

Committee member Francis Cadell offered to ship the supplies to Adelaide and then inland across the Murray and Darling Rivers , where they could have been picked up en route. But because Cadell had opposed Burke's appointment as expedition leader, Burke turned down his offer. Instead, everything was loaded onto wagons, three of which collapsed under their load after a short time.

Camels

Camels have already been used successfully in desert exploration in other parts of the world . However, by 1859 only seven camels had been imported into Australia .

The Victoria government ordered George James Landells to purchase 24 dromedaries in India . The camels reached Melbourne in June 1860. The committee bought six more animals from George Coppins Cremorne Gardens . The camels were initially housed in the stables by the Parliament Building in Melbourne . They were later moved to the Royal Park. 26 camels were included in the expedition. Two camels with their two foals and two stallions stayed in the Royal Park.

Course of the expedition

departure

The expedition began on August 20, 1860 at around 4 p.m. in front of around 15,000 spectators in Royal Park Melbourne .

Heavy rains and bad roads made the onward journey through Victoria difficult and exhausting. The group reached Lancefield on August 23 , where they set up their fourth camp. This means that the expedition covered 92 kilometers in three days. The first major break was on Sunday, August 26th, 1860, in the sixth camp in Mia Mia .

The expedition reached Swan Hill on September 6, 1860 and arrived in Balranald on September 14, 1860 . There they left the sugar, lemon juice, weapons and ammunition they had brought with them to reduce their weight. On September 24, in Gambala , Burke decided to redistribute the loads and load some supplies onto the camels for the first time, and to lighten the load on the horses by ordering each man to continue on foot. He also set the personal baggage of each participant at 30 pounds (14 kg). Due to long-term differences between Landells and Burke, Landells resigned on October 8, and the doctor Hermann Beckler did the same a little later. Landells and Burke's point of contention was the camels that Landells should take care of. Burke, however, interfered again and again in the care. The resignation came after an open dispute between Landells and Burke, which was triggered by the rum of the expedition. After some men got drunk, Burke wanted to leave the rum behind, but Landells was against it. In the course of the dispute, Burke verbally abused his deputy and claimed he was being badly advised. Wills took over the post of Burke's deputy. They reached Menindee on October 12, 1860, and had thus taken two months to travel 750 kilometers from Melbourne to Menindee, a distance that a stagecoach could cover in little more than a week. Burke set up the first depot in Menindee. At this point, two of the five officers in the expedition had resigned, 13 other members had been fired and eight new ones had been hired.

Burke was concerned that the rival Stuart could reach the north coast more quickly and grew increasingly impatient with their slow progress, as they often only traveled two miles an hour. Burke split up the group; he himself rode on with Wills and six other men on October 29th to reach Cooper Creek as quickly as possible , the other group was to follow. The trip was relatively easy as water was abundant due to rainfall and the weather was unusually mild, with temperatures only exceeding 32 ° C twice. At the Torowotto Swamp , Wright was sent back to Menindee alone to fetch the remaining men and provisions.

Cooper Creek

In 1860, Cooper Creek was the border of the land explored by Europeans; Charles Sturt in 1845 and Augustus Gregory in 1858 had advanced to this river . Burke reached Cooper Creek on November 11 and set up a depot at the 63rd camp on the upper reaches of Cooper Creek, the Barcoo River, while they continued to explore the area to the north. A plague of rats forced the men to move camp. They founded a second depot further downstream at the Bullah-Bullah waterhole at the 65th camp, provided it with a palisade and named the place "Fort Wills".

In order not to have to travel in the hot Australian summer, Burke was originally supposed to stay at Cooper Creek until March 1861. Still, Burke only held out until December 16, when, impatiently because of the delay of the Menindee troops, he decided to hurry ahead to the Gulf of Carpentaria . He divided the group again: this time William Brahe remained in charge of the camp with Dost Mahomet, William Patterson and Thomas McDonough. Burke, Wills, John King and Charles Gray set out with six camels, a horse and provisions for just three months. Burke told Brahe to wait three months, but Wills secretly asked him to extend the wait to four months. It was now midsummer in Australia with maximum daily temperatures of 50 ° C in the shade. This heat hit the expedition members all the more because shade was seldom found due to the sparse vegetation.

Gulf of Carpentaria

Apart from the prevailing heat, the trip was easy as the group still found enough water because of the past rains and the Aborigines were peaceful. On February 9, 1861, they reached the Little Bynoe River , a tributary in the delta of the Flinders River , where they found that they could not reach the sea because the mangrove swamps in front of them were impassable. Burke and Wills left the camels and King and Gray at the 119th camp on the Little Bynoe River and set out on horseback through the swamps, but turned back after 15 miles and set off with King and Gray on their way back to the Cooper Creek depot. By the time they turned back, their supplies were already critically short. They still had food for 27 days, but had already taken 57 days to get there from Cooper Creek.

On the way back, the rainy season began, which brought tropical monsoons with it. A camel was left behind on March 4th because it could not go any further. Three more camels were shot on the way and their meat ate. The lone horse was shot dead on April 10 on the Diamantina River , south of what is now the city of Birdsville . Equipment had to be left behind in various locations as the number of pack animals decreased.

To stretch their supplies, they ate purslane . Gray also caught a five-kilogram python (probably Aspidites melanocephalus , a black- headed python ), which they also ate. Burke and Gray then got dysentery . Gray was severely weakened, but because he had long complained of illness, the other three thought he was a simulator. On March 25th, Gray was caught stealing skilligolee, a watery pulp, for which he was beaten by Burke. As of April 8th, Gray could no longer walk. He died on April 17th of the dysentery at a place they called "Polygonum Swamp" ("Knotweed Swamp"). The site was later named Lake Massacre by the South Australian rescue expedition and is located in South Australia . The three surviving men paused a day to bury Gray and to recover, as they were meanwhile badly marked by hunger and exhaustion.

Return to Cooper Creek

Burke, Wills and King returned to the depot on the evening of April 21, 1861, but found it abandoned. That morning Brahe had left Cooper Creek for Menindee because one of his men had broken a leg. In addition, supplies were running out and it seemed unlikely to the depot crew that Burke would return, but to be on the safe side they buried some supplies and an explanatory letter under a tree and marked the spot. (See section Dig Tree )

The three men dug up the hiding place and found the letter, but were too exhausted and had no hope of catching up with the main group. They decided to rest and recover, using up the supplies from the hiding place. Wills and King wanted to follow the "old trail" back to Menindee, but Burke decided to follow the river. In this way he wanted to reach the furthest rural settlement outpost in South Australia, a large cattle ranch near Mount Hopeless . That meant a 240-kilometer journey south-west across the desert. They wrote a letter explaining their intentions and buried it in the hiding place under the marked tree in case a rescue team searched the area. They didn't change the label on the tree or the date on the tree, which later turned out to be a mistake. On April 23, they made their way through the Strzelecki Desert towards Mount Hopeless.

Meanwhile, on the way back to Menindee, Brahe met Wright trying to get supplies to Cooper Creek. The two agreed to go back to camp on Cooper Creek to see if Burke had come back after all. When they reached their destination on May 8, Burke and Wills were already 35 miles away. With the tree's marking unchanged, Brahe and Wright concluded that Burke had not returned. They did not consider checking that the supplies were still buried in place, but returned to the main group at Menindee.

Burke, Wills and King at Cooper Creek

After Burke, Wills, and King left the Dig Tree , they never traveled more than eight kilometers (five miles) a day. Of the two remaining camels, one was irretrievably stuck in a watering hole and the other died. Without pack animals, the three explorers could not carry enough water with them to later leave the river and leave the Strzelecki Desert towards Mount Hopeless, so they were forced to return to Cooper Creek. Their supplies were almost out and they were depleted. The Aborigines at Cooper Creek, the Yandruwandha tribe , gave them fish and beans called padlu and a type of bread made from the fruiting bodies of the ngardu (Nardoo; Marsilea drummondii ) in exchange for sugar .

Wills returned to the Dig Tree to bury his diary, notepad, and log in their hiding place for safekeeping. In his diary, Burke sharply criticized Brahe for leaving no provisions or animals.

Burke and Wills passed away

The three men lived on Cooper Creek . They collected ngardu seeds for food and took fish and fried rats from the Yandruwandha.

In late June 1861, Burke and King decided to move upstream to Dig Tree. They wanted to see if a search party had arrived there by now. Wills had grown too weak to go on, and at his insistence they left him at the Breerily watering hole with some food and water. Burke and King ran another two days before Burke couldn't go any further. He died the next morning. King stayed with his body for two days before returning downstream to the Breerily watering hole. But Wills had also passed away in the meantime. King found shelter with the Yandruwandha tribe, where he stayed for three months until he was rescued.

The exact days of Burke and Wills' deaths are unknown. Various dates are given on monuments in Victoria. The exploration committee determined June 28, 1861 as the death date for both explorers.

Cause of death

Little did the discoverers know that Ngardu seeds contained thiaminase , which deprives the body of vitamin B1 ( thiamine ). They probably did not prepare the bush bread , which was a staple food for the local population, in the Aboriginal way. It is believed that they did not paste the seeds into a paste, which would have been necessary to wash out the thiaminase. Despite eating, the men grew weaker and weaker. Wills wrote in his diary:

“My heart rate is 48 and it's very weak. My arms and legs are almost nothing but skin and bones. I can only keep an eye out for something like Mr. Micawber, but the starvation from Nardoo is by no means unpleasant, because despite the feeling of weakness and the inability to move, he gives me the greatest satisfaction, especially when you consider my appetite . "

Burke and Wills likely died of a vitamin B1 deficiency called beriberi . This is underscored by King's report, which states that Burke complained of pain in his legs and back shortly before his death.

Dig Tree

The tree at the depot on which Brahe marked the location of the buried supplies is an approximately 250-year-old eucalyptus ( Eucalyptus coolabah ). Originally the tree was known as "Brahe's Tree" or "Depot Tree" ("Brahes Tree" or "Depot Tree"). When the tree Burke died under, he received a great deal of attention and interest. Due to the marking and subsequent popularity of Frank Clune's book Dig , the tree later became known as the "Dig Tree". Two of the three markings are overgrown today, only the camp number is still legible.

The tree has three markings:

- on the one hand the camp number: the initial B for Burke over LXV , the Latin spelling of the number 65.

- on the other side of the tree was carved on one branch DEC 6-60 over APR 21-61 . The dates represent the period during which Brahe was there.

- on the other branch was the eponymous Dig mark: AH over DIG over under over an arrow pointing to the right. However, this was later added by a member of Alfred Howitt's search expedition , not by Brahe .

Brahe's Dig mark was believed to be on a tree south of the dig tree to which the horses were tied. Accordingly, the supplies were not buried on the dig tree, but under the "horse tree". At least this can be seen from surveys, diary entries and old photos. In 1899, John Dick carved Burke's face into a nearby tree.

Rescue expeditions

A total of six expeditions were sent out to rescue Burke and Will. Two of them took the sea route to look for the missing in the Gulf of Carpentaria, the others approached the interior from different directions. They made an important contribution to the exploration of Australia, as each expedition explored the surrounding area in the search.

Victorian Contingent Party

After no news from Burke for six months, demands were made in the press to clarify the whereabouts of the research expedition. The public pressure became so strong that the scouting committee could no longer ignore the demand and agreed in a meeting on June 13 to send a four-person search expedition to track down Burke and Wills' expedition and, if necessary, offer them assistance. The Victorian Contingent Party was the first expedition to look for Burke and Wills. She left Melbourne on June 26, 1861 under the direction of Alfred William Howitt.

On the Loddon River , Howitt met Brahé, who had left Cooper Creek. Brahé had no news from Burke either, and Howitt realized that a much larger expedition would be needed to save Burke. Howitt left the other three men in his group on the Loddon River and traveled with Brahé to Melbourne to brief the Exploration Committee of the new situation. On June 29th he sent a telegram to John Macadam , on June 30th the committee met and decided to set up a twelve-person search expedition under Howitt's command, with which he should advance to Cooper Creek and then follow in Burke's footsteps. On September 3, the group reached Cooper Creek, on September 11, Dig Tree, and on September 15, they found living John King with an Aboriginal tribe on Cooper. Over the next nine days, during which King was supposed to recover, Howitt also found the bodies of Burke and Will and buried them. On November 6th, King was back in Melbourne. However, he was in poor health and never recovered from the rigors of the journey. He passed away eleven years later.

Victorian Exploring Party

The Victorian Exploring Party was the second expedition led by Alfred Howitt. At a meeting of the committees, von Mueller spoke out in favor of the recovery of the bodies of Burkes and Wills on November 13, 1861. On December 9, Howitt set out with twelve others in the direction of Cooper Creek. He was supposed to follow the Route Burkes and retrieve the "remains of the unfortunate explorers" and bring them back for a solemn burial in Melbourne. After long stays in Menindee and Mount Murchison , the group arrived at Cooper Creek on February 25, 1862 and set up camp at the Cullyamurra waterhole. From there Howitt went on numerous excursions into the surrounding area. On April 13, he exhumed Burke and Will's bodies. In the following six months he explored the Australian hinterland. On November 22nd, Howitt set out for Clare, where he arrived on December 8th. Only with the doctor he rode on to Adelaide, the rest of the crew was supposed to take the corpses of Burke and Will by train. Howitt reached Adelaide on December 9th, the rest on December 12th. Burke and Wills were brought to Melbourne on December 29th.

South Australian Burke Relief Expedition

The South Australia contingent was led by John McKinlay from Adelaide . McKinlay found the presumed remains of Charley Gray in Polygonum Swamp in October 1861. He found another grave there and assumed a mass murder on the expedition, which is why he called the place "Lake Massacre" (massacre lake).

Victorian Relief Expedition

In 1861, Frederick Walker led the Victorian Burke and Wills Relief Expedition . The group consisted of twelve mounted men, seven of whom were Aboriginal and members of the Native Mounted Police Force . They set out from Rockhampton on September 7, 1861 with the aim of reaching the Gulf of Carpentaria . They found Burke's footsteps and followed them to Burke's northernmost camp. On December 4th they massacred an Aboriginal group in the evening hours, in which twelve people died. On December 7th, William Henry Norman, captain of HMS Victoria , and Walker met on the Gulf Coast.

HMCSS Victoria

The HMCSS Victoria (HMCSS = His / Her Majesty's Colonial Steam Sloop) was steered by William Henry Norman into the Gulf of Carpentaria to look for survivors of the expedition. Before that, it was used in the first Taranaki War in New Zealand. When Burke and Will's expedition went missing in July 1861, the Victoria was ordered to Brisbane. It was from there that the Queensland Relief Expedition set sail on the SS Firefly . On December 7th, Norman met with Frederick Walker.

Queensland Relief Expedition

The Queensland Relief Expedition set off from Brisbane with the SS Firefly on August 24, 1861 under the leadership of William Landsborough . From November Landsborough mainly explored the region on the Gulf Coast. He later turned south and crossed Australia in a north-south direction until he reached Melbourne in October 1862. He was considered the first explorer to cross Australia from north to south and was honored with £ 2,000 for his services to the exploration of the Gulf Coast.

Reasons for the failure of the expedition

After questioning the surviving participants, the retrospective commission of inquiry identified Wright as responsible for the failure of the expedition. After Landell's departure, Burke split up the group in Menindee and sent Wright back with part of the crew to provide replenishment. Burke, meanwhile, moved with the rest of the troop on to Cooper Creek, where he was supposed to stay for the summer. Wright didn't show up at the time, however, and Burke, worried that Stuart might arrive at the Gulf before him, left early and with insufficient provisions to the north. The group's strengths were thus overworked. Because Wright couldn't get to Cooper Creek, the camp was deserted when Burke returned from the Gulf. From the Commission's point of view, Wright's delay brought the expedition to a standstill.

Alan Moorehead wrote of the "mystery" of Wright's lateness:

“There was no reason for a criminal case against Wright here, but he was publicly convicted as the main culprit and that was a reputation he could not possibly ever shed. He went into hiding in Adelaide, leaving behind the small but persistent mystery: Why was he really late? Was it just because he wanted to secure his income? Was it because he didn't want to miss his wife and family and the comforts of populated areas? Was it just that he was stupid, lazy, and indifferent: a man too narrow-minded to think of anyone but himself? Or is it simply possible that he too was a victim of the same fateful chain of errors that plagued the expedition from the start? Those were questions that can never be finally answered. "

An in-depth study of Wright's actions was part of Thomas Bergin's master's thesis at the University of New England . Bergin showed that Wright was in a precarious position due to a lack of money and a lack of pack animals to carry the supplies. His inquiries to the exploratory committee were not processed until early January. The great heat and lack of water at this time of year meant that the tour group made extremely slow progress. She was harassed by Bandjigali and Karenggapa (clans of the Murris), and three men, Ludwig Becker, Charles Stone and William Purcell, died of malnutrition on the trip. On the way north, Wright camped at the Koorliatto waterhole on the Bulloo River while trying to find Burke's trail to Cooper Creek.

The resigned Landell, on the other hand, blames Burke's weak leadership for the failure of the expedition. In his declaration of resignation to the exploration committee in November 1860, he predicts the failure of the expedition. There he makes serious allegations against Burke. Specifically, he criticizes Burke's inexperience, which is why he lacked any leadership. Burke used a rough tone, did not listen to the advice of others, often changed his mind and sabotaged Landell's efforts to protect the camels. Burke found the camels, which Landells considered essential to a successful expedition, to be a burden and treated them badly. Landells complains that the camels suffered from the heavy rain and the bad roads during the first stage, which Burke did not understand. He was willing to simply leave behind exhausted camels. In addition, there were long day walks of 20 to 30 miles and unsuitable resting places without enough feed for the cattle. According to Landell's report, the animals on the Darling River were already so exhausted that the pack horses , for example , lay down on the road to rest. The improper handling of the cattle resulted in the loss of several camels. He also threw away ghee and oatmeal , which were important for the camels' diet. He also did not seek advice, which annoyed the experienced expedition participants.

Landells describes not only the bad treatment of the animals, but also Burke's behavior towards men. Burke fired many men he did not like and replaced them with men of his choice. Some of those who were dismissed for drunkenness did not suit him, even if they were qualified. As an example, Landells cites John Drakeford, who was the cook of the expedition and already had experience with expedition companies. Drakeford lived most of the time in South Africa under Boers and was a member of the Cape Mounted Police . He could have taken part in David Livingstone's expedition to Africa. He was involved in the transport of horses from the Cape to India, and he also knew a lot about camels.

Everyone except Burke and Wills had to walk; Burke and Wills took the right to ride horses. Burke also installed a spy system and had two men in the camp who kept their ears peeled and reported to him.

Aftermath

Although the expedition itself is to be regarded as a failure, the search expeditions made an important contribution to the exploration of the continent. McKinlay , Walker and Landsborough in particular were able to develop a lot of pastureland on their travels. They shed new light on regions that were previously thought to be barren deserts. After 1862 there was no longer any doubt that there was seasonally good grazing land in the hinterland that ranchers could hardly ignore.

Despite their failure, Burke and Wills were honored after their death. The discoverers were granted a state funeral at Melbourne Central Cemetery, which was reportedly attended by 40,000 spectators. In their honor, monuments were also erected in many cities along their route: in 1862 a monument was erected in the city of Castlemaine . This is where Burke was stationed before the expedition. Four years after the expedition ended, on April 21, 1865, a bronze statue of Burkes and Wills was unveiled in Melbourne. That was the day of my return to Cooper Creek. John King, the sole survivor, was present at the ceremony.

The towns of Bendigo , Ballarat and Fryerstown also donated monuments. In 1890 a memorial was erected in Royal Park, the starting point of the expedition. In 1983 the Australian Post honored her memory with a postage stamp showing her portraits. The city of Burketown is named after Robert Burke.

Her public reputation as a hero changed over time, until in 1888 a commission from the New South Wales government described the expedition as a "perverse absurdity". As a result, many of the monuments in Victoria were dismantled and the annual commemorations no longer took place at the end of the century.

In 1985 the film Burke & Wills was shot about the expedition with the main actors Jack Thompson as Burke and Nigel Havers as Wills.

literature

- Thomas John Bergin: In the Steps of Burke and Wills. Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney 1981, ISBN 0-642-97413-6 (English).

- Thomas John Bergin: Across the Outback. Readers Digest, Surrey Hills 1996, ISBN 0-86449-019-4 (English).

- Tim Bonyhady: Burke and Wills . From Melbourne to Myth. David Ell Press, Balmain 1991, ISBN 0-908197-91-8 (English).

- Max Colwell: The Journey of Burke and Wills. Paul Hamlyn, Sydney 1971, ISBN 0-600-04137-9 (English).

- David Corke: The Burke and Wills Expedition . A Study in Evidence. Educational Media International, Melbourne 1996, ISBN 0-909178-16-X (English).

- Sarah Murgatroyd: The Dig Tree. Text Publishing, Melbourne 2002, ISBN 1-877008-08-7 (English).

- Willi Stegner: Pocket Atlas of Geographical Discoveries . Klett , Gotha / Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-12-828131-5 .

Contemporary literature

- The Burke and Wills exploring expedition: an account of the crossing the continent of Australia, from Cooper's Creek to Carpentaria, with biographical sketches of R. O'Hara Burke and WJ Wills . Wilson and Meckinnon, Melbourne 1861, books.google.ch .

- Supplementary pamphlet to the Burke and Wills exploring expedition: containing the evidence taken before the commission of inquiry appointed by government, with portraits of John King and Charles Gray . Wilson & Mankinnon, Melbourne 1861.

- Andrew Jackson: Robert O'Hara Burke and the Australian Exploring Expedition of 1860. Smith, Elder & Co. , London 1862, books.google.ch

- Burke and Wills Commission: Report of the commissioners appointed to inquire into and report upon the circumstances connected with the sufferings and death of Robert O'Hara Burke and William John Wills, the Victorian explorers . J. Ferres, Melbourne [1862?].

- William John Wills: A successful exploration through the interior of Australia: from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria . Richard Bentley, London 1863, full text .

- August Diezmann: Horrible outcome of a voyage of discovery . In: The Gazebo . Issue 8, 1862, pp. 124–126 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- Burke & Wills Web A comprehensive website containing many historical documents relating to the Burke and Wills expedition, in English

- The Burke & Wills Historical Society The "Burke & Wills Historical Society"

- Terra Incognita Burke and Wills Internet Exhibition at the State Library of Victoria

- Burke and Wills collection in the Australian National Museum (English)

Individual references and comments

- Martin Mulligan, Stuart Hill: Ecological pioneers: A Social History of Australian Ecological Thought and Action . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2001, ISBN 0-521-00956-1 , books.google.com.au .

- Ernest Scott: Australia, Part 1 . In: Cambridge History of the British Empire , Volume 7, Part 1, Cambridge 1988, ISBN 0-521-35621-0 , books.google.com.au .

- Ed Wright: Lost Explorers: Adventurers who disappeared off the face of the earth . Murdock Books, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-74196-139-3 , books.google.de .

- ^ Scott, p. 123

- ^ Scott, p. 133

- ^ Scott, p. 134

- ^ Scott, pp. 136, 137

- ↑ a b c d Mulligan, p. 61

- ↑ a b c Scott, p. 142

- ^ The Fundraising Committee at burkeandwills.net.au , accessed July 6, 2010

- ^ Wright, p. 258

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Scott, p. 143

- ↑ Leader of the expedition , accessed on March 10, 2010.

- ^ Expedition assistants at burkeandwills.net.au , accessed March 10, 2010

- ↑ Indians to look after the camels on burkeandwills.net.au , accessed on March 10, 2010

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k members , accessed on March 10, 2010

- ↑ a b King on burkeandwills.net.au

- ↑ List of costs on burkeandwillsweb.nt.au

- ↑ a b c d e Contribution of the State Library of Victoria on the expedition , course from Melbourne to Menindee

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Wright, p. 259

- ↑ Camels for the expedition at burkeandwills.net.au , accessed on March 10, 2010

- ↑ List of all camels on burkeandwillsnet.net.au , accessed on May 27, 2010

- ↑ a b Landell's written statement on his resignation , accessed on June 14, 2010

- ↑ History, Chapter 8 at burkeandwills.net.au , accessed May 27, 2010

- ^ Interview with King , questions 845, 849. Retrieved June 12, 2010

- ^ Wright, p. 260

- ^ Interview with King , Questions 944-946. Retrieved June 12, 2010

- ↑ a b c Wright, p. 262

- ^ Scott, pp. 143, 144

- ↑ a b Scott, S. 144

- ↑ Calder Chaffey: A Fern which Changed Australian History. In: Australian Plants online. Association of Societies for Growing Australian Plants, June 2002, accessed January 17, 2016 .

- ↑ a b Wright, p. 263

- ↑ Solving the DIG TREE MYSTERY, p. 7

- ^ Victorian Contingent Party on Burke & Wills Web , accessed May 28

- ^ Quote from Mueller , at the top of the page, accessed on June 14, 2010

- ^ Victorian Exploring Party at burkeandwills.net.au , accessed May 29, 2010

- ↑ SABER on burkeandwills.net.au

- ^ Victorian Relief Expedition on burkeandwills.net.au , accessed June 5, 2010

- ↑ HMCSS Victoria at burkeandwills.net.au , accessed June 5, 2010

- ^ AER on burkeandwills.net.au , accessed June 5, 2010

- ↑ Queensland Relief Expedition on burkeandwills.net.au

- ^ Report of the investigative commission on burkeandwills.net.au , accessed on June 14, 2010

- ↑ Thomas John Bergin: Courage and Corruption . An analysis of the Burke and Wills Expedition and the subsequent Royal Commission of Inquiry. 1982 (MA Honors thesis, University of New England (Armidale)).

- ↑ Bulletin, May 2005: 125 moments that changed Australia, p. 68

- ^ Information on australianstamp.com , accessed on March 10, 2010

Remarks

- ↑ The list contains only a selection of personalities from public life at the time. The number of members changed over time.

- ↑ In the southern hemisphere, autumn begins in March

- ↑ Wilkins Micawber: Character from Charles Dickens' novel David Copperfield