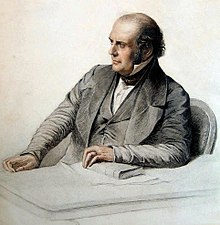

Guglielmo Libri

Count Guglielmo Brutus Icilius Timeleone Libri Carucci dalla Sommaia (born January 1, 1803 in Florence , † September 28, 1869 in Fiesole , Italy ) was an Italian-French mathematician and bibliophile who became famous for his enormous book thefts.

Life

youth

Guglielmo Libri Carucci dalla Sommaia came from one of the oldest Florentine noble families. His parents were Count Giorgio Libri-Carrucci dalla Sommaia , Count of Bagnano, and Rosa del Rosso . Libri's early childhood was marked by the difficult relationship between his parents, who finally divorced in 1807.

In 1816 he began to study law at the University of Pisa , but soon switched to mathematics and the natural sciences. In the year of his graduation, 1820, he published his first work, "Memoria sopra la teoria dei numeri" (Memorandum on Number Theory), which was acclaimed by leading mathematicians such as Charles Babbage , Augustin Louis Cauchy and Carl Friedrich Gauß .

In 1823 he was appointed professor of mathematical physics in Pisa , but quickly realized that he had neither great inclination nor special aptitude for academic teaching. In the following year he succeeded in taking leave of absence due to illness while continuing to pay his salary; by Ferdinand III. he was appointed professor emeritus. It is believed, however, that Libri used his poor health as an excuse to get his father released from prison in Paris. Libri traveled to Paris, where he made the acquaintance of the most famous French mathematicians of his time such as Sophie Germain , Pierre-Simon Laplace , Siméon Denis Poisson , Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier , André-Marie Ampère , Augustin Louis Cauchy and François Arago , and the encounters in his In diary. Libri presented his studies at the Académie des sciences and it was in this context that he met François Guizot .

In the summer of 1825, Libri returned to Italy. On his return, Libri was appointed library director by the Accademia dei Georgofili , but he gave up the post in December 1826. In addition, on his return to Italy, Libri joined the secret society of the " Carbonari ", which fought for a liberal constitution in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.

In 1829 Libri traveled to Milan and from there via Turin to Paris , where he deciphered Leonardo da Vinci's manuscripts in the Bibliothèque Mazarine and checked their authenticity.

Career in France

In 1830 Libri apparently took part in the July Revolution in France, which brought the “citizen king” Louis-Philippe I to power, which subsequently gave him political influence. Towards the end of 1830, Libri traveled to Tuscany to surprise Leopold II in the Teatro della Pergola and to force him to sign a constitution. The project was finally carried out in January 1831, but failed and Libri was banished from Florence. François Arago initially took care of the almost destitute emigrant who began to work for the Revue des Deux Mondes in 1832 .

In February 1833, Libri became a French citizen and, on the intercession of Aragos, was given a teaching position at the Collège de France , where he worked as an assistant to Sylvestre Lacroix . Arago was also the permanent secretary of the Académie des sciences, of which Libri was elected to succeed Adrien-Marie Legendre in March of the same year . An influence of Arago on the election cannot be ruled out, but also not proven. In November 1834, Libri was appointed as the successor to Hachette as a lecturer in probability calculus at the natural science faculty of the Sorbonne , in 1839 he was appointed full professor of mathematics there and in 1843 (against the competition of Augustin Louis Cauchy and Jean-Marie Duhamel ) as the successor to Lacroix held the chair of mathematics at the Collège de France, which he held until 1845. He was also awarded the Legion of Honor in 1837 . Since 1838 he was also a member of the editorial board of the Journal des Sçavans . Due to his rapid career, his ambition and his behavior, which was sometimes perceived as arrogant, he made enemies of a number of mathematicians, which also contributed to the fact that he was not a native of France. As early as 1835, his friendship with Arago had broken down for unknown reasons. A particularly bitter opposition linked Libri with Joseph Liouville , with whom he regularly fought violent arguments in the meetings of the Academy. His opponents questioned the originality of his work and criticized the cumbersome and not very elegant argumentation.

It is possible that this scientific controversy contributed to Libri shifting his main field of work to the history of mathematics. In addition to smaller writings on mathematical physics, in particular on heat theory , as well as on number theory and the theory of equations , he wrote his main scientific work during this time, the "Histoire des sciences mathématiques en Italie, depuis la rénaissance des lettres jusqu'à la fin du dix- septième siècle ” (History of Mathematical Sciences in Italy from the Renaissance to the End of the 17th Century), published in four volumes from 1838–1841 (reprinted in 1989). Two more volumes were planned, but were never completed. Although Libri tends to exaggerate the achievements of Italian mathematicians at the expense of mathematicians in other countries, Libri's knowledge of even remote facts makes the work extremely informative, not least because it is based on a careful study of the original sources. Among other things, he studied Leonardo da Vinci's manuscripts for his book and printed some of these manuscripts for the first time in the appendices. Libri developed into a passionate collector of books and autographs , so that he was finally able to draw on around 1800 manuscripts , letters and books by Pierre de Fermat , Galileo Galilei , René Descartes , Marin Mersenne and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz , among others . Among them were numerous manuscripts that had previously been believed lost. Although Libri claimed to have acquired everything legally, it later emerged that some of the books had been stolen, for example from the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence.

Due to the extensive knowledge of book history he had acquired in his historical work and collecting activities, but above all thanks to his friendship with the influential politician François Guizot , Libri became secretary of the commission for the general manuscript catalog of French public libraries in 1841 (Commission du Catalog général des manuscrits des bibliothèques publiques de France ) During the French Revolution , by order of the Welfare Committee, the confiscated books from the possession of the "aristocrats" were given to the public libraries. 50 years later, these collections were still not systematically inventoried and cataloged. Libri's job was to go to libraries across France and sift through their books and manuscripts. He used this activity for extensive theft of books and manuscripts. His official position gave him free and unattended access to all public libraries and thus gave him ample opportunity to obtain valuable books and manuscripts undisturbed. One of the libraries particularly affected was the city library in Orléans , which in 1842 lost valuable manuscripts from the former inventory of Fleury Abbey to Libri . Through his thefts, Libri eventually brought together a huge collection of enormous value. In 1847 he owned approximately 40,000 books and manuscripts. He sold parts of his collection for large sums; To the Earl of Ashburnham , a British collector, he sold 2,200 volumes of manuscripts for 200,000 francs in 1847 , and further book sales in the same year brought in more than 100,000 francs (the daily wage of a worker was then about four francs).

In 1842, Libri was first suspected through an anonymous complaint. However, the police investigations were only very discreet because of Libri's prominent position and came to nothing. In 1845 Libri wrote to his long-time friend Antonio Panizzi , director of the library of the British Museum , saying that selling the stolen goods in France was probably too risky for him. Panizzi sent his colleague Sir Frederic Madden to Paris, but ultimately the financial means were lacking and the collection went to Bertram Ashburnham, the 4th Earl of Ashburnham . Only after another complaint in July 1847 did the police find out, among other things, that a Theocritus edition by Aldus Manutius from 1495, which Libri had sold in August 1847, had disappeared from the library of Carpentras . Even now, out of political consideration, only a report was initially drawn up to the Minister of Justice, which he presented to the Prime Minister - Libri's friend and patron Guizot . It was not until the February Revolution of 1848 , which led to the fall of Guizot , that Libri was in immediate danger. However, he was warned in good time by a journalist friend and avoided the threat of arrest and charge by fleeing to England. Before that, he managed to get his most valuable books and manuscripts out of the country in 18 large boxes. When they were supposed to be confiscated in Le Havre , they were already on the ship en route to England.

Stay in England

In London, Libri posed as a political refugee and was supported by Antonio Panizzi, with whom he was well known from previous book sales. Panizzi, himself a native of Italy, as well as large parts of the British public believed Libri's claims that the allegations against him were baseless and that he was discriminated against and persecuted in France because of his Italian origins and his praise for Italian mathematics. Through Panizzi's mediation, Libri became friends with the eccentric mathematician Augustus De Morgan , who became his most vehement defender and wrote numerous articles in favor of libris. Libri himself publicly denied the accusations made against him (Réponse au rapport de M. Boucly , 1849).

In the criminal case, which opened against Libri in absentia before the Paris Court of Appeal in the spring of 1850, however, the theft of numerous valuable books and manuscripts from the Bibliothèque Mazarine and the library and archive of the Institut de France in Paris and the libraries in Troyes , Montpellier , Grenoble and Carpentras convincingly proven. On June 22, 1850, Libri was found guilty of theft and sentenced to ten years in prison. Libri's friend, the archaeologist and writer Prosper Mérimée , Inspector General of Historic Monuments, who publicly sided with him, was also brought to justice for this reason and received 15 days' imprisonment and a fine of 1,000 francs. Libri also lost its membership in the French Academy of Sciences. He continued to have friends and defenders in France, Italy and England. In 1861, the French Minister of Justice tried to rehabilitate him, which was rejected by the French Senate.

Although Libri had come to England with nothing but his books and manuscripts, he lived there in pleasant circumstances and led a lively social life. His income came from the sale of books and manuscripts. In 1861 he organized two large auctions; the catalog he created for this purpose includes 7628 numbers. In total, Libri is said to have made over a million francs through its sales. Libris auctions provided a major impetus for establishing scientific books as collectibles.

When his health deteriorated in 1868, Libri returned to Italy from England and moved into a villa in Fiesole (Tuscany), where he died on September 28, 1869. His body was buried in the San Miniato al Monte cemetery.

About 2,000 manuscripts that Libri stole in Italy and sold in London were bought back by the Italian government in 1884 and are now in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana . Léopold Delisle , director of the Bibliothèque Nationale , was able to prove beyond any doubt that the manuscripts sold to Lord Ashburnham in 1847 had been stolen from French libraries. After lengthy negotiations between the French and British governments, most of the valuable manuscripts were brought back to France in 1888.

Fonts

- Memoria di Guglielmo Libri sopra la teoria dei numeri (1820)

- Histoire des sciences mathématiques en Italie, depuis la rénaissanace des lettres jusqu'à la fin du dix-septième siècle (1838–1841)

- Essai sur la vie et les travaux de Galilée (1841)

- Catalog of the Mathematical, Historical, Bibliographical and Miscellaneous Portion of the Celebrated Library of M Guglielmo Libri (1861)

See also

literature

- Acte d'Accusation contre Libri-Carucci (indictment at the trial of 1850, in French)

- Johannes Willms : Nomen est crimen - the Libri affair . in: Almanach 1977. Cologne: Heymanns, 1977

- P. Alessandra Maccioni Ruju, Marco Mostert: The Life and Times of Guglielmo Libri (1802-1869). Scientist, Patriot, Scholar, Journalist and Thief. A nineteenth century story. Lost, Hilversum 1995, ISBN 90-6550-384-6 .

- Adrian Rice: Brought to book. The curious story of Guglielmo Libri (1803–69) (PDF file; 3.9 MB) . In: Newsletter of the European Mathematical Society . No. 48, June 2003, ISSN 1027-488X , pp. 12-14.

- Umberto Bottazzini : Libri . In: Joseph W. Dauben , Christoph J. Scriba (eds.): Writing the history of mathematics. Its historical development . Birkhäuser, Basel et al. 2002, ISBN 3-7643-6167-0 ( Science networks 27).

- Livia Giacardi: Libri, Guglielmo. In: Mario Caravale (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 65: Levis-Lorenzetti. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2005, pp. 60-64.

- PR Harris: Libri, Guglielmo [Count Guglielmo Bruto Icilio Timoleone Libri-Carrucci dalla Sommaia]. In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew, Brian Harrison (Eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , from the earliest times to the year 2000 (ODNB). Volume 33: Leared-Lister. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-861383-0 , ( oxforddnb.com license required ), As of 2004, accessed July 29, 2020.

Web links

- Literature by and about Guillaume Libri in the catalog of the German National Library

- John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson : Guglielmo Libri. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive .

- Libri, Guglielmo Icilio Timoleone, conte Carrucci della Somaia. In: Enciclopedie on line. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o P. R. Harris: Libri, Guglielmo [Count Guglielmo Bruto Icilio Timoleone Libri-Carrucci dalla Sommaia] (1802–1869), scientist, book collector, and thief . In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew (ed.): The Oxford dictionary of national biography: from the earliest times to the year 2000 . 1st edition. 33: Leared - Lister. Oxford University Press, Oxford 23 September 2004.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Livia Giacardi: Libri, Guglielmo. In: Mario Caravale (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 65: Levis-Lorenzetti. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2005, p. 60.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Livia Giacardi: Libri, Guglielmo. In: Mario Caravale (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 65: Levis-Lorenzetti. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2005, p. 61.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Livia Giacardi: Libri, Guglielmo. In: Mario Caravale (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 65: Levis-Lorenzetti. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2005, p. 62.

- ↑ Cf. Marco Mostert: The library of Fleury: A provisional list of manuscripts . Hilversum Verloren Publishers, 1989, ISBN 90-6550-210-6 .

- ↑ a b c d e Livia Giacardi: Libri, Guglielmo. In: Mario Caravale (ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 65: Levis-Lorenzetti. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 2005, p. 63.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Libri, Guglielmo |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Libri Carucci, Guglielmo; Libri Carucci della Somaia, Guglielmo; Libri Carucci dalla Sommaja, Guglielmo Brutus Icilius Timeleone; Libri Carucci dalla Sommaja, Guglielmo; Libri, Guillaume |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian mathematician, physicist and book thief |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 1, 1803 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Florence |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 28, 1869 |

| Place of death | Fiesole |