Averroes

Abū l-Walīd Muhammad ibn Ahmad Ibn Ruschd ( Arabic أبو الوليد محمد بن أحمد ابن رشد, DMG Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad Ibn Rušd ), Ibn Ruschd for short , Latinized Averroes - also Avérroes or Averrhoës - (born April 14, 1126 in Córdoba ; died December 10, 1198 in Marrakech ), was an Andalusian philosopher , lawyer, Doctor and Arabic-speaking writer . He was court physician to the Berber dynasty of the Almohads of Morocco.

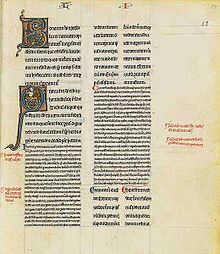

Averroes wrote a medical encyclopedia and almost every work of Aristotle a comment . In the Christian scholasticism of the Middle Ages , on which he exerted great influence, he was therefore simply referred to as " The Commentator " (" il commentator " coined by Dante ), just as Aristotle was occasionally called "the philosopher". Averroes was so important that Raphael included a representation of Averroes in his fresco The School of Athens .

Averroes saw logic as the only way man can become happy. The Aristotelian logic gave him the possibility to come from the data of the senses to the knowledge of the truth. For him logic was the law of thought and truth.

Live and act

Averroes was born in Córdoba in 1126 into a family of lawyers. He studied law, medicine and philosophy and was also a very educated person. In 1168 or 1169 he is said to have been introduced by Ibn Tufail to Prince Abu Yaqub Yusuf I , who asked him in a conversation what the philosophers' view of the eternity of heaven was. Averroes, however, was intimidated and claimed not to be concerned with philosophy. So the prince began a conversation with Ibn Tufail and showed his great knowledge of Islamic philosophy and its issues. Averroes then began to interfere in the conversation and was finally commissioned to rearrange and comment on all of Aristotle's works in order to give Islam "pure and complete science". He led a diverse life that did not spare politics, he was a judge in Córdoba and Seville in 1169 and in 1182 he became the personal physician of Abu Yaqub, who had meanwhile become caliph. However, he only held this position for a short time and was again a judge in his hometown. The unfavorable political conditions affecting all Spanish-Arab philosophers at that time also applied to Ibn Ruschd; the Islamic rulers did not need them, but rather the support of theologians. Averroes' calls on people to use their reason brought him into conflict with the views of Islamic orthodoxy . Under Caliph Yaʿqūb al-Mansūr (1184–1199), the son and successor of Abu Yaqub, Averroes was initially in the favor of the ruler, but in 1195 he fell out of favor. The caliph, who was on a campaign in Spain, believed he was dependent on the support of Orthodox forces. Therefore Averroes was exiled to Lucena , a small town south of Cordoba; his works were banned and their cremation ordered. Averroes was only allowed to return to Marrakech in 1197, where he died in 1198. He was first buried in Marrakech, later his body was brought to the family grave in Cordoba.

Work and philosophy

Averroes was an open and critical spirit of his time. In his preoccupation with Aristotle he proceeded as systematically as possible and interpreted him like no one before. He wrote commentaries in several gradations, shorter, medium and larger, and made a name for himself as a commentator on Aristotle. Even Dante mentions him in this capacity in his Divine Comedy . For Averroes, Aristotle is the most perfect person, who was in possession of the infallible truth and who only showed himself to people once. He was reason incarnated. His own philosophy is based very much on logic, as would be expected from a great Aristotelian. It begins with the question of whether one should philosophize at all, whether it is permitted, forbidden, recommended or necessary under religious law. In verses of the Koran such as “Think, who have insight!” Averroes not only finds the invitation to Muslims to reflect on their beliefs, but also to find the best possible evidence for their thinking, and this he sees clearly in philosophy and especially given in the Aristotelian argument. But Averroes also restricts that not all people can deal with philosophy, only those who have a strong intellect. In response to al-Ghazālī , he divides the Koran and its exegesis into three groups in his work “The decisive treatise”:

- Clear and evident verses that are straightforward and understandable for everyone (such as "There is no God but God")

- In their statement, clear verses, which can also be interpreted and reflected on by people with a strong intellect (for example, “The Merciful has sat on the throne”, for “simple ones” to understand that God is like a king on the throne sit while "people with a strong intellect" already recognize God's claim to power)

- Verses for which it is not clear whether they are to be understood literally or figuratively and for which the opinion of the scholars may therefore also differ (e.g. verses about the resurrection or the like)

But then he attacks al-Ghazālī even more directly in his work The Incoherence of Incoherence , the title is based on al-Ghazālī's The Incoherence of the Philosophers . There al-Ghazālī had attacked the philosophers mainly because they taught disbelief on the basis of three things:

- The originality of the world

- God's knowledge of individual things only in a general way

- The possible resurrection of man only with the soul, but not the body

Averroes responded to these three points as follows:

- The Koran say anywhere that the world should be created out of nothing and came in time. In the six days of creation, according to the Koran, God's throne even floated “over the water”, from which it can be assumed that the world could already have existed. Averroes assigns such verses to the third group of Quranic verses, because of the interpretation of which no one can be accused of unbelief.

- The philosophers do not claim that God has no knowledge of individual things. They emphasize, however, that it is different from human knowledge and that human beings cannot know what God knows. Their knowledge arises step by step, while God's knowledge from eternity encompasses all things and is therefore a prerequisite for the individual things to arise one after the other.

- Nor do the philosophers deny the resurrection and do not teach anything that contradicts the Koran. He also assigns these verses to the third group of Koranic verses. So nobody should be accused of disbelief based on a “different” interpretation.

This is where his own philosophical system begins. However, there are no more independent works here, but his teaching extends to his numerous commentaries and compendia on Greek authors, although he was not able to speak Greek. According to Aristotle, the truth was lost. He accuses Avicenna and others of having connected philosophy with theology and thus made philosophy vulnerable to people like al-Ghazālī in the first place. Averroes, like almost all Islamic philosophers, also dealt with the intellect or reason. So not every person has his own individual potential intellect that enables him to be happy. Because there is only one universal potential intellect. The individual has only those activities at his disposal which are related to physical existence, which are coordinated by a soul, a soul that is connected to the body and goes away with it. Spiritual knowledge therefore does not belong in the realm of the individual.

Jacob Anatoli (around 1194–1256) translated the works of Averroes from Arabic into Hebrew .

Medical work

In his medical works Averroes dealt with the fever theory of Galen and Avicennas . In smaller works he also dealt with drugs and pharmacology. The most important medical work is his Kitāb al-kullĩyāt fī'ț-țibb (literally the book of collected works on medicine , translated into Latin as Liber universalis de medicina ). The history of the impact of this book was far-reaching. It has had a decisive influence on medicine in the West. Averroes dealt here with anatomy, with physiology and pathology. Food theory, medicine, hygiene and therapy were also dealt with. In many places criticism of Galen became clear, not only in the fever theory, but also in a treatise on elements and symptoms of illness. He also frequently cited Galen critically in his Theriak tract ( Maqāla fī't-tiryāq ), which also deals theoretically with dosages and whose reception was the basis for a complex quantifying pharmacy.

Honorary names

Carl von Linné named the genus Averrhoa of the wood sorrel family (Oxalidaceae) in his honor .

The lunar crater Ibn-Rushd was named after him.

The Ibn Rushd Goethe Mosque in Berlin-Moabit , founded by Seyran Ateş , was named after him.

See also

Averroism , Ibn Rushd Prize , Islamic philosophy

Text editions and translations

- Arabic (partly with translations)

- Maroun Aouad (ed.): Averroès (ibn Rušd): Commentaire moyen à la Rhétorique d'Aristote . 3 volumes, Vrin, Paris 2002, ISBN 2-7116-1610-X (critical edition with French translation and commentary)

- Charles E. Butterworth (translator): Averroes' Three Short Commentaries on Aristotle's "Topics", "Rhetoric", and "Poetics". State University of New York Press, Albany 1977, ISBN 0-87395-208-1 (critical edition with English translation)

- Heidrun Eichner (Ed.): Averroes: Middle Commentary on Aristotle's De generatione et corruptione. Schöningh, Paderborn 2005, ISBN 3-506-72899-7 (critical edition with commentary)

- Alfred L. Ivry (Ed.): Averroës: Middle Commentary on Aristotle's De anima. Brigham Young University Press, Provo (Utah) 2002, ISBN 0-8425-2473-8 (critical edition with English translation)

- Colette Sirat, Marc Geoffroy: L'original arabe du grand commentaire d'Averroès au De anima d'Aristote. Prémices de l'édition. Vrin, Paris 2005, ISBN 2-7116-1749-1 (with French translation)

- David Wirmer (Ed.): Averroes: About the intellect. Excerpts from his three commentaries on Aristotle's De anima. Arabic, Latin, German. Herder, Freiburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-451-28699-5 .

- Rüdiger Arnzen (Ed.): Averroes on Aristotle's Metaphysics. An Annotated Translation of the So-called Epitome (= Scientia Graeco-Arabica. 5). De Gruyter, Berlin 2010 ( books.google.de ).

- German

- Patric O. Schaerer (translator): Averroes: The decisive treatise. The investigation into the methods of evidence. Reclam, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-15-018618-3 .

- Helmut Gätje : Aristotle's 'Parva Naturalia' in the processing of Averroës. Research on Arabic Philosophy. Dissertation , Tübingen 1955.

- Helmut Gätje: The epitomes of the 'Parva Naturalia' of Averroës . Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1961.

- Frank Griffel (translator): Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Rushd: Relevant treatise Faṣl al-Maqāl. Verlag der Weltreligionen, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-458-70026-5 .

- Max Horten (transl.): The Metaphysics of Averroes (1198 †) translated into Arabic and explained. Minerva, Frankfurt a. M. 1960 (reprint of the 1912 edition).

- Max Horten (transl.): The main teachings of Averroes according to his writing: The refutation of Gazali. Marcus and Webers Verlag, Bonn 1913.

- Marcus Joseph Müller (transl.): Philosophy and theology of Averroes. VCH, Weinheim 1991, ISBN 3-527-17625-X (reprint of the Munich 1875 edition; contains: al-Kashf'an Manabij al-Adilla fi'Aqa'id al-Milla; Fasl al-Maqal; al-Daminah, facsimiles at archive.org ).

- Simon van den Bergh (transl.): The epitoms of the metaphysics of Averroes, translated and provided with an introduction and explanations. Brill, Leiden 1970 (reprint of the 1924 edition).

- English

- Charles E. Butterworth (transl.): Averroes' Middle Commentary on Aristotle's Poetics. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1986, ISBN 0-691-07302-3 .

- Charles E. Butterworth (translator): Averroes' Middle Commentaries on Aristotle's Categories and De Interpretatione. Princeton University Press, Princeton 1983, ISBN 0-691-07276-0 .

- Helen Tunik Goldstein (transl.): Averroes' Questions in Physics. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht 1991, ISBN 0-7923-0997-9 .

- Simon van den Bergh (translator): Averroes' Tahafut al-tahafut (The Incoherence of the Incoherence). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1987, ISBN 0-906094-04-6 (reprint of 1954 edition; two volumes in one).

- French

- Laurence Bauloye (translator): Averroès: Grand commentaire (Tafsīr) de la Métaphysique. Livre Bêta. Vrin, Paris 2002, ISBN 2-7116-1548-0 .

- Ali Benmakhlouf, Stéphane Diebler: Averroès: Commentaire moyen sur le De interpretatione. Vrin, Paris 2000, ISBN 2-7116-1441-7 .

- Aubert Martin (translator): Averroès: Grand commentaire de la Métaphysique d'Aristote. Livre Lam-Lambda. Les Belles Lettres, Paris 1984, ISBN 2-251-66234-0 .

- Latin (medieval and humanistic)

- Averrois Cordubensis colliget libri VII. Cantica item Avicennae cum eiusdem Commentariis. In: The medical compendia of Averroes and Avicenna (= Aristoteles: Opera Volume 10), Minerva, Frankfurt am Main 1962 (reprint of the Venice 1562 edition) [humanistic translation].

- Bernhard Bürke (Ed.): The ninth book (Θ) of the Latin great metaphysics commentary by Averroes. Francke, Bern 1969.

- Francis James Carmody, Rüdiger Arnzen, Gerhard Endress (eds.): Averrois Cordubensis commentarium magnum super libro De celo et mundo Aristotelis . 2 volumes, Peeters, Leuven 2003, ISBN 90-429-1087-9 and ISBN 90-429-1384-3 ( books.google.de ).

- Gion Darms (Ed.): Averroes: In Aristotelis librum II (α) metaphysicorum commentarius. The Latin translation of the Middle Ages on a handwritten basis with an introduction and a study of the history of the problem. Paulusverlag, Freiburg (Üechtland) 1966.

- Francis H. Fobes (Ed.): Averrois Cordubensis commentarium medium in Aristotelis de generatione et corruptione libros. Mediaeval Academy of America, Cambridge (Mass.) 1956 ( medievalacademy.org PDF).

- Marc Geoffroy, Carlos Steel (ed.): Averroès: La béatitude de l'âme. Vrin, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-7116-1519-7 [inauthentic work wrongly attributed to Averroes; contains teachings of Averroes, but comes from a Jewish philosopher]

- Roland Hissette (Ed.): Commentum medium super libro peri hermeneias Aristotelis. Translatio Wilhelmo de Luna attributa. Peeters, Leuven 1996, ISBN 90-6831-859-4 .

- Roland Hissette (Ed.): Commentum medium super libro praedicamentorum Aristotelis. Translatio Wilhelmo de Luna adscripta. Peeters, Louvain 2010, ISBN 978-90-429-2282-2 .

- Ruggero Ponzalli (Ed.): Averrois in librum V (Δ) metaphysicorum Aristotelis commentarius. Francke, Bern 1971.

- Horst Schmieja (Ed.): Commentarium magnum in Aristotelis physicorum librum septimum (Vindobonensis, lat. 2334). Schöningh, Paderborn 2007, ISBN 978-3-506-76316-7 .

- Emily L. Shields, Harry Blumberg (eds.): Averrois Cordubensis compendia librorum Aristotelis qui parva naturalia vocantur. Mediaeval Academy of America, Cambridge (Mass.), Versio Hebraica 1949 ( medievalacademy.org PDF); versio Arabica 1972 ( medievalacademy.org PDF)

- Frederick Stuart Crawford (Ed.): Averrois Cordubensis commentarium magnum in Aristotelis de anima libros. Mediaeval Academy of America, Cambridge (Mass.) 1953 ( medievalacademy.org PDF).

- Beatrice H. Zedler (Ed.): Averroes' Destructio Destructionum Philosophiae Algazelis in the Latin Version of Calo Calonymos. Marquette University Press, Milwaukee 1961

- multilingual digital edition

literature

- GC Anawati, Ludwig Hödl, Hermann Greive, HH Lauer: Avveroes, Averroismus . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 1, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7608-8901-8 , Sp. 1291-1296.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Averroes. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 308-309.

- André Bazzana, Nicole Bériou, Pierre Guichard: Averroès et l'averroïsme, XII e –XV e siècle, un itinéraire historique du Haut Atlas à Paris et à Padoue: actes du colloque international organisé à Lyon, les 4 and 5 October 1999. Presses universitaires de Lyon, Lyon 2005, ISBN 2-7297-0769-7 .

- Jameleddine Ben Abdeljelil: Ibn Ruschd's philosophy read interculturally. Traugott Bautz, Nordhausen 2005, ISBN 3-88309-163-4 .

- Emanuele Coccia: La trasparenza delle immagini. Averroè e l'averroismo. Mondadori, Milano 2005, ISBN 88-424-9272-8 .

- Michael Fisch : "Religion makes dealing with philosophy an obligation." Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Rushds fasl al-amaqal. In: Michael Fisch: “See man is truly lost.” Contributions to Aur'ân and Islam research (2011-2019). Weidler, Berlin 2019, pp. 177-185, ISBN 978-3-89693-741-4 .

- Raif Georges Khoury: Averroes (1126–1198) or the triumph of rationalism. Winter, Heidelberg 2002, ISBN 3-8253-1265-8 .

- Anke von Kügelgen: Averroes and Arab Modernism. Approaches to a new foundation of rationalism in Islam. Brill, Leiden / New York / Cologne 1994 (= Islamic Philosophy, Theology and Science. Texts and Studies. Volume 19), ISBN 90-04-09955-7 .

- Thomas Kupka, Averroes as a legal scholar, in: Rechtsgeschichte 18 (2011), 214–216 ( papers.ssrn.com PDF).

- Oliver Leaman: Averroes and his Philosophy. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1988, ISBN 0-19-826540-9 .

- Hermann Ley : Ibn Ruschd. In: Philosophers' Lexicon . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1982, pp. 421-426 with bibliography .

- S. Gómez Nogales: La psicología de Averroes. Comentario al libro sobre el alma de Aristóteles. Madrid 1987.

- Markus Stohldreier: On the concept of the world and creation in Averroes and Thomas v. Aquin. A comparative study. Grin, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-640-34740-7 ( freidok.uni-freiburg.de ).

- Dominique Urvoy: Le monde des Ulémas andalous du V / XIe au VII / XIIIe siècle. Geneva 1978.

- Dominique Urvoy: Averroès - Les ambitions d'un intellectuel musulman. Paris 2008.

- Markus Zanner: Construction features of the Averroes reception - a religious studies contribution to the reception history of the Islamic philosopher Ibn Ruschd. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-631-36629-9 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Averroes in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Averroes in the German Digital Library

- H. Chad Hillier: Ibn Rushd (Averroes) (1126-1198 CE). In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- North Rhine-Westphalian Academy of Sciences and Arts , position in the Thomas Institute: Averroes-Latinus

- Islamic Philosophy Online - Philosophia Islamica: Brief portrait, texts and secondary information (in English and Arabic)

- The Philosophy and Theology of Averroes . Tractacta, translated from the Arabic by Mohammad Jamil-Ub-Behman Barod (Baroda: Manibhai Mathurbhal Gupta, 1921).

- ( In Physicam 20, In De Anima 5 and 20) (in Latin)

- Bibliography on Averroës Digital Averroes Research Environment: manuscripts, incunabula and full texts

Remarks

- ↑ The morning of the world: Bernd Roeck . 1st edition. CH Beck, 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-69876-7 , pp. 273 .

- ↑ Barry S. Kogan: Averroes and the Metaphysics of Causation . St Univ of New York, 1985, ISBN 0-88706-063-3 , pp. 10 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Charles E. Butterworth : The Political Lessons of Avicenna and Averroes. In: I. Fetscher, H. Münkler (Hrsg.): Piper's manual of political ideas. Volume 2: Middle Ages. From the beginnings of Islam to the Reformation. Munich / Zurich 1993, pp. 141–173.

- ^ Maria Rosa Menocal: The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain . Little, Brown, 2009, ISBN 978-0-316-09279-1 ( books.google.com [accessed August 16, 2016]).

- ^ HA Davidson: Alfarabi, Avicenna, and Averroes on Intellect: Their cosmologies, theories of the active intellect, and theories of human intellect. New York / Oxford 1992.

- ↑ Rudolph, Ulrich: Islamic Philosophy. From the beginning to the present . CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-50852-9 , p. 70-76 .

- ↑ Arabic كتاب الكليات في الطب

- ↑ Arabic مقالة في الترياق

- ^ Heinrich Schipperges : Averroës. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart , Christoph Gradmann : Ärztelexikon. From antiquity to the 20th century. CH Beck Munich 1995, pp. 28-29; 2nd Edition. Springer, Berlin 2001, p. 17; 3rd edition, ibid. 2006, pp. 17-18; Print version ISBN 978-3-540-29584-6 .

- ↑ Michael McVaugh : Theriac at Montpellier 1285-1325 (with an edition of the "Questiones de tyriaca" "" of William of Brescia). In: Sudhoff's archive. Volume 56, 1972, pp. 113-144.

- ↑ Gundolf Keil: The anatomei-term in the Paracelsus pathology. With a historical perspective on Samuel Hahnemann. In: Hartmut Boockmann, Bernd Moeller , Karl Stackmann (eds.): Life lessons and world designs in the transition from the Middle Ages to the modern age. Politics - Education - Natural History - Theology. Report on colloquia of the commission to research the culture of the late Middle Ages 1983 to 1987 (= treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen: philological-historical class. Volume III, No. 179). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1989, ISBN 3-525-82463-7 , pp. 336–351, here: p. 339.

- ^ Carl von Linné: Critica Botanica. Leiden 1737, p. 91.

- ↑ Carl von Linné: Genera Plantarum. Leiden 1742, p. 201.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Averroes |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Averroës; Ibn Rushd; Abu l-Walid Muhammad bin Ahmad bin Rushd; Averrhoës |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Arab philosopher, doctor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 14, 1126 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cordoba |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 10, 1198 |

| Place of death | Marrakech |