Roman road

The Roman roads are roads that were built and maintained during the time of the Roman Empire . Many of them stretch across Europe for thousands of kilometers . Its approximate course including the most important traffic junctions was mapped in the historical Tabula Peutingeriana .

General

Roman roads were a novelty in Central Europe. Because of their technical road structure, they were, in contrast to the nature trails of Germanic and Celtic origin (see Altstraße ), not only passable largely independently of the moisture in the soil, but also made their way as straight as possible, with only comparatively small inclines, their way through plains and with engineering structures such as Retaining walls and bridges through the mountains . The fortification was carried out by a predetermined layer structure of the streets, which differed in the regional availability of certain building materials.

Four types can be distinguished:

- The via publica ("state road"): here the administration of Rome acted as planner and builder and had it built at the expense of the state treasury. Such streets were built by soldiers, forced laborers and prisoners, whose skeletal remains are evidence of the efforts to build such streets.

- The via militaris ("Heerstraße") was characterized by strategic and logistical aspects. For her, too, the State of Rome was the planner, builder and sponsor.

- The via vicinalis ("provincial road") was, as the name suggests, built and maintained by the provinces.

- The via privata ("private road") played a major role in Roman provincial history, as it represents the connection between the manors and the civil settlements.

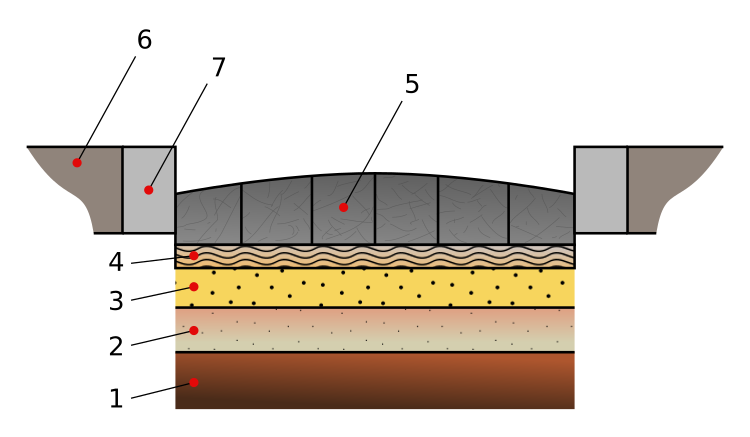

For a Roman road, clearing and always excavation to a depth of more than one meter was necessary to secure the ground. After that, coarse stones (statumen), then gravel (rudus and nucleus) and then sand, increasingly finer layers, were applied until the pavement was made with paving stones to a specified width. Curbs formed channels in the construction.

1 Grown soil, leveled and firmly tamped

2 Statumen: Fist-sized stones

3 Quarry stones , cement and clay

4 Nucleus: Nut-sized pebbles, pieces of cement, stone fragments and clay

5 Dorsum or agger viae: the arched surface (media stratae eminentia) made of hewn stones, flint or Basalt, stone blocks depending on the area. The shape of the surface ensured that the rainwater ran off and the lower layers remained dry

6 Crepido, margo or semita: elevated footpath on both sides of the street

7 Eckstein

The cobblestones were ideal for marching, riding and also for the traffic with ox carts. In the course of time, of course, there was certain wear and tear on the ceiling, which still exists today. There are still numerous examples of extremely well-preserved Roman roads. Most of the time, however, these fragments are no longer integrated into public road traffic, which is most likely due to the fact that the width is too narrow for today's traffic and oncoming traffic . A number of today's roads are built on the foundations of Roman roads, although the original foundations and the road surface were naturally widened and, as a rule, the Roman road is largely invisible today due to an asphalt cover over a separating layer. The A15 north of Lincoln, for example, still precisely follows the 34 kilometers long dead straight Roman road, with only a single bulge at Scampton ; there the runway of the air force base was extended around 1955, which made the first change of the course necessary after around 1900 years.

The technique of stone paving for highways was introduced mainly under Gaius Iulius Caesar , when he was proconsul in Gaul . Pavement for inner-city streets was practiced for the cities on the Mediterranean long before the turn of the century. The military importance of stone paving should not be underestimated. With Roman roads it was possible for the first time to move troops quickly and in large numbers from one place to another in order to retain control and conquer new territories. At the same time, the Romans also built forts . For this task, among other things, the ruled people were used for bondage; work slaves were also used. In a harsher climate , a frost-proof substructure was (and is) a prerequisite for weatherproof roads.

Miliaria (Roman milestones) were often set up along the Roman roads to provide orientation.

Romans on the Limes and Amber Road

The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes was built to militarily secure the shortest possible Roman highway from Mainz to Augsburg .

The trade routes for the coveted amber to the Mediterranean , known as the Amber Road, led from the German and Russian Baltic coasts through Poland and Austria (Marchfeld in Lower Austria) to the Adriatic Sea to Aquileia , a western branch from Hamburg to Marseille . The winter-proof connection between Carnuntum on the Danube (approx. 40 km east of Vienna) and Aquileia in Italy is called the Roman Amber Road; its first section between Aquileia and Ljubljana (Colonia Emona) was the Via Gemina .

At transport hubs - e.g. B. on the imperial border of the Limes on the Danube - market places emerged early on . In Lower Austria , particularly high-quality Roman roads were built for military reasons (frequent conflicts with the Teutons ). There, about 50 km east of Vindobona (today's Vienna ), Carnuntum , the capital of the province of (Upper) Pannonia , was the largest Roman city on the Limes.

See also

literature

- Friedrich Carl Ferdinand von Müffling: Via the Roman roads on the right bank of the Lower Rhine: starting from the Vetera winter camp, to Veste Aliso, over the pontes longi to the Marsen and the lower Weser . Mittler, Berlin 1834 ( digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf ).

- Friedrich Wilhelm Schmidt, ed. from Ernst Schmidt: Research on the Roman roads etc. in the Rhineland . In: Yearbooks of the Society of Friends of Antiquity in the Rhineland. 31, 1861, pp. 1-220 (online resource, accessed March 3, 2012).

- Josef Hagen: Roman roads of the Rhine province (= explanations of the historical atlas of the Rhine province . Volume 8 ). 2. rework. u. increased circulation. Bonn 1931 ( http://www.ub.uni-koeln.de/cdm/ref/collection/grhg/id/44837 Scan of the 1st edition Bonn 1923 [accessed on September 2, 2018]).

- Harm-Eckart Beier: Investigation of the design of the Roman road network in the Eifel, Hunsrück and Palatinate areas from the perspective of the road construction engineer . Braunschweig 1971 (Diss. Univ. Braunschweig Fac. F. Construction).

- Raymond Chevallier: Les voies romaines . Colin, Paris 1972.

- Hans Bauer: The Roman highways between Iller and Salzach according to the Itinerarium Antonini and the Tabula Peutingeriana. New research results on route guidance . Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-8316-0740-2 .

- Arnold Esch : Roman roads in their landscape: the afterlife of ancient roads around Rome. With information on inspecting the site . Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2023-X .

- Werner Heinz: Routes of antiquity. On the move in the Roman Empire . Stuttgart, Theiss 2003, ISBN 3-8062-1670-3 . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-16853-4 .

- Margot Klee: Lifelines of the Empire. Roads in the Roman Empire . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2307-1 . ( Review )

- Thomas Pekáry : Investigations into the Roman imperial roads. (= Antiquitas, series 1: Treatises on ancient history. 17). Habelt, Bonn 1968.

- Michael Rathmann : Investigations into the Reichsstraßen in the western provinces of the Imperium Romanum (= supplements of the Bonner Jahrbücher. 55). Zabern, Mainz 2003, ISBN 3-8053-3043-X .

- Josef Stern: Roman wheels in Raetia and Noricum. Out and about on Roman paths (= Roman Austria 15th 2002). Vienna 2003.

Web links

- Roman roads in Germany (with various maps)

- Antikefan - Roman roads, bridges and tunnels

- Roman driving transit over the Julier-Mittelland-Jura passes on standardized tracks with a gauge of 106 - 107 cm

- Roman road Neckar-Alb-Aare

- Via Rhenana. Project Römerstrasse on the Upper Rhine. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015 ; accessed on November 28, 2015 .

- Thomas Codrington: Roman Roads in Britain (published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, 1903)

- Roman Roads in the Mediterranean. ( Memento of May 23, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (in English, Greek, French, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish)

- Pilgrimage routes in Spain, e.g. Sometimes on Roman roads (with map; opens in a separate window)

- Traianus; Sections: "Viae" and "Vias Romanas" ( Memento of September 21, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (English, French and Spanish)

- Rhaetian pictures of visible remains of Roman roads between Kempten, Augsburg, Salzburg and Tyrol

- Viae (article by William Ramsay)

- Roman road Via Claudia - Roman road construction in general as well as a photographic documentation of the Via Claudia between Augsburg and Epfach

- Via Numidica (Roman road in North Africa)

- Viae Roma, consular streets of Rome

- Hans Bauer: Military logic and course of the Roman roads in the Bavarian area