Krauss Maffei

| KraussMaffei Group

|

|

|---|---|

| legal form | Company with limited liability |

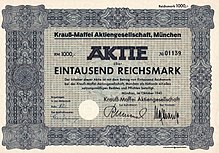

| founding | 1838 |

| Seat | Munich , Germany |

| management | Michael Ruf (CEO) |

| Number of employees | 5,134 (2019) |

| sales | 1.37 billion euros (2017) |

| Branch | mechanical engineering |

| Website | www.kraussmaffeigroup.com |

Today, the KraussMaffei Group is a mechanical engineering company based in Munich . Today's group employs over 5,000 people worldwide and has been owned by a consortium since April 2016 , which consists of the Chinese state company ChemChina and the state fund Guoxin International.

In addition, there are two other former parts of the group at the Munich-Allach location that now operate independently:

- the arms company Krauss-Maffei Wegmann

- the locomotive construction division, today part of the Mobility division of the Siemens group .

history

Company in the 19th century

Krauss-Maffei came into being when the factory for steam locomotives founded by JA Maffei in Munich-Hirschau in 1838 became insolvent as a result of the global economic crisis in the course of 1930 and was taken over by the competitor Krauss & Comp. (founded in Allach in 1860 ). Up until then, both were leading German manufacturers of locomotives of various types.

Company in the 20th century

Since 1908, steam rollers have also been manufactured at Maffei . In 1927 Maffei began to manufacture vehicles (road tractor under French license ). Krauss, too, was already engaged in the construction of trucks in the late 1920s - in cooperation with the Swiss company Berna . After the company merged to form Krauss-Maffei, the facilities in Munich-Hirschau were given up in 1938 and the 60-hectare Munich-Allach site, which still exists today, was expanded.

During the Nazi dictatorship , in addition to the so-called " Eastern workers ", prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates from the more than 400 camps and accommodations in the greater Munich area were obliged to do forced labor . They made up the majority of the workforce. At the end of 1942 there were 8,849 employees. 3943 of these were German employees. There were 3543 conscripted foreigners, including many Italians. 1363 prisoners of war, especially French (from 1940) and Russians (from 1941), were employed.

After the Second World War, Krauss-Maffei received an order from the US military administration to build buses in the undestroyed factory in Munich-Allach. On November 14, 1945, the production license for 200 vehicles was granted. The design and construction of buses was an important area of business until the 1960s. But also the repair of locomotives as well as the construction of small locomotives and 30 tractors took place immediately after the war.

The company belonged to the Buderus Group (KF Flick Group ) in Wetzlar , was then gradually acquired by the Mannesmann Group between 1989 and 1996 and merged with Mannesmann DEMAG in 1999 to form Mannesmann Demag Krauss-Maffei.

Company in the 21st century

Mannesmann Demag Krauss-Maffei was sold to Siemens as part of the takeover of Mannesmann by Vodafone ; it initially belonged to Atecs Mannesmann AG , an industrial holding company owned by Siemens, before being sold on to the US subsidiary KKR in 2002 .

The company has been building injection molding machines since 1957 . The plastics machine production of Krauss-Maffei has had the legal form of a GmbH since 1986. At this time, a number of specialist companies from the injection molding and extrusion industry were integrated into the company, including Maschinenfabrik Seidl GmbH , a specialist in rubber and rotary injection molding . In January 1998 this area was assigned to Mannesmann Plastics Machinery GmbH (MPM), Munich. MPM was sold to the US subsidiary Madison Capital Partners in 2006 and has been trading under the name KraussMaffei AG or its operating subsidiary KraussMaffei Technologies GmbH since the end of 2007 .

From 2012 to 2016, the company was owned by the Canadian financial investor Onex Corporation .

Chinese owned since 2016

Since April 2016, Krauss-Maffei has been owned by the Chinese state company ChemChina . Since the end of 2018 the company has been known as KraussMaffei Company Ltd. listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. After the transaction, ChemChina held a good 60 percent of the shares, another Chinese sovereign wealth fund around 15 percent, and the rest was free float. At the same time, production in China was accelerated: In addition, the ChemChina majority holding Qingdao Tianhua Institute of Chemistry Engineering (THY) took over a ChemChina plant in Sanming, which builds injection molding machines for the Chinese market.

In 2018 Krauss-Maffei celebrated the company's 180th anniversary.

In November 2018, the company was the victim of a ransomware attack.

In 2019 there was a realignment of the operational areas and the bundling in the business areas: injection molding technology, extrusion technology and reaction technology. The Krauss-Maffei and Netstal brands were combined under the umbrella brand, but Netstal was retained as the product name. Netstal-Maschinen (Näfels / Switzerland) will operate under the name "Krauss Maffei High Performance AG" in the future. Also Krauss-Maffei Berstorff was transferred to the umbrella brand and acts as the "Krauss Maffei Extrusion GmbH".

From 2022 onwards, the company will move its headquarters and location in Allach in phases to an industrial park currently under construction in the municipality of Vaterstetten north of the village of Parsdorf.

Krauss-Maffei will cut 510 jobs worldwide by 2023, the majority of them in Germany, as the company announced in early 2020.

Business areas and locations

The KraussMaffei Technologies GmbH emerged in 2007 from the former Mannesmann Plastics Machinery GmbH (MPM) (1998-2007). The main roots are the companies Krauss-Maffei Kunststofftechnik GmbH, Munich , Netstal, Näfels (Glarus / Switzerland) and Berstorff, Hanover .

The group of companies is the world market leader in machines and systems for the plastics and rubber producing and processing industry. It offers three different process technologies: Machines and systems for injection molding and reaction technology ( polyurethane technology ) are offered under the Netstal and KraussMaffei brands . Under the KraussMaffei Berstorff brand, machines and systems for the extrusion technology of polymers and rubber .

On November 8, 2013, the company announced that it would close the plant in Treuchtlingen , a parts supplier with around 150 employees, by March 2015 and move the production and assembly of injection molding machines to Munich and Sučany , Slovakia. After fierce resistance from the workforce (demonstration, vigil), the plant was closed on November 28, 2013. A future contract for the location was signed in autumn 2015 - the location will continue to operate.

In Sučany , Slovakia , a switch cabinet construction was initially set up for the group, later component production and finally the assembly of complete injection molding machines.

Other companies in the group are KraussMaffei Automation GmbH and Burgsmüller GmbH .

In the course of the takeover by ChemChina , the locations in Europe are to be linked with those in China. ChemChina operates three plants in southern China for the construction of plastics machines: In Sanming , Yiyang and Guilin . In planning, the three plants in China are to specialize and their production is to be linked with the machine and systems technology from KraussMaffei Technologies . In Sanming, components are to be manufactured initially, followed by injection molding machines. The other two plants will be geared towards system technology for compounding in tire production, based on the know-how of KraussMaffei Berstorff .

Former business areas

In the mid-1990s, the Krauss-Maffei operating companies in Munich consisted of the dependent companies (including subcontractors):

- Krauss-Maffei Defense Technology

- Krauss-Maffei traffic engineering

- Krauss-Maffei plastics technology

- Krauss-Maffei process engineering

- Krauss-Maffei automation technology

- Krauss-Maffei service

The Krauss-Maffei, built up as a conglomerate, had its own drop forge until 1980 and an open-die forge until mid-1988. The civil sector of Krauss-Maffei in the field of plastics technology was strengthened through acquisitions in the 1990s. Then there were the companies Netstal, based in Nafels (Switzerland), later Berstorff, based in Hanover and finally the DEMAG Kunststofftechnik group based in Schwaig . These companies were brought together with Krauss-Maffei Kunststofftechnik GmbH under the umbrella of Mannesmann Plastics Machinery (MPM) (1998–2007) based in Munich. The Demag Plastics Group was spun off from the newly formed KraussMaffei Group in 2008 and operates today as Sumitomo (SHI) Demag Plastics Machinery GmbH .

Defense technology

The company was already producing tracked and armored vehicles in the 1930s . During the Second World War , it completely switched production to armaments production , particularly to tank construction. Krauss-Maffei delivered over 5,800 half-track vehicles to the German Wehrmacht between 1934 and 1944 . In addition, the production of gearboxes and internal combustion engines was started under licenses from the Friedrichshafen gear factory (ZF) (1939) and Maybach Motorenbau GmbH (1943).

With the rearmament , the defense technology was reactivated. In 1963 Krauss-Maffei was awarded the contract for the Leopard tank series (replaced by the Leopard 2 in 1979 ); In 1976, the Gepard anti-aircraft cannon went into production after 10 years of development. Whereas the share of the defense sector in turnover in 1983 was still over DM 1.7 billion, in 1987 it fell to a little over DM 800 million. Since the civil areas were in the red at the same time, the business areas were divided into individual GmbHs and managed by Krauss-Maffei AG as dependent management GmbHs.

As part of the acquisition by Mannesmann, and its dependence on financial markets, analysts and fund managers, was placed the arms deal in question removed, Thus, the merged Krauss-Maffei Defense Technology GmbH in 1999 with the smaller, family-run defense company Wegmann & Co. from Kassel to Krauss-Maffei Wegmann GmbH . The cooperation between Wegmann and Krauss-Maffei existed for decades before the merger; Wegmann had for many Krauss-Maffei tanks a. a. the gun turrets delivered. To "tank family" of the group included not only battle tanks and armored engineer vehicle, air defense , artillery, reconnaissance and armored personnel carrier . Even today, as in the time of the Leopard 2, the majority of exports take the form of production licenses or cooperative productions with the participation of national industry.

Traffic engineering - bus construction and special vehicles

For the construction of the omnibuses ordered by the American occupiers after the Second World War , Krauss-Maffei chose the type of front-wheel drive bus with a rear engine, which had only been attempted in Germany by Pekol (1938) . In addition, numerous problems such as the air supply to the engine, the remote control of the transmission in front of the rear axle and the display of speed and temperature at the driver's seat had to be solved. On February 19, 1946, the first test drive of the prototype , which was manufactured entirely in- house, took place; it had the license-manufactured Maybach HL 64 TUK engine, a 6.2-liter six-cylinder carburettor engine with 130 hp. From autumn 1946 the series vehicles with the designation KMO 130 (Krauss-Maffei-Omnibus with 130 HP) were delivered. Due to the very difficult material procurement, only a few of the numerous orders (190 by January 20, 1947) could be fulfilled. The situation only improved after the currency reform in 1948 .

Krauss-Maffei initially limited itself to the construction of the chassis , the superstructures were mainly produced by the Josef Rathgeber wagon factory in Munich, and from 1948 also by other body construction companies such as Kässbohrer Fahrzeugwerke . Starting in 1949, chassis were increasingly provided with their own bodies, e.g. B. also as an overland mail car on KMO 131 for the Deutsche Post , which was used to sort the mail during the journey. In 1950 the first self-body buses (KMO 133) were mass-produced. In 1950 Krauss-Maffei manufactured the first German bus with an automatic transmission , the “Diwabus 200 D” from Voith . In addition, the company's first own engine, a 6-cylinder two-stroke diesel engine with the designation KMD 6, was produced. Six buses were equipped with these engines in the rear (KMO 140), with two others the engine was placed on the left in front of the rear axle ( mid-engine bus KMO 142). The latter two were delivered to Stadtwerke Dortmund with a body from Westwaggon as cars 35 and 36.

Together with the Nordwestdeutsche Fahrzeugbau GmbH (NWF) in Wilhelmshaven, in which Krauss-Maffei was involved, the KML 90 and KML 110 lightweight buses with a self-supporting lattice construction were created based on plans by aircraft designer Henrich Focke , with a streamlined body and a low drag coefficient of 0 , 4–0.5 c w . From 1954, the KML bodies were also manufactured at Krauss-Maffei.

From 1988 the aircraft towing system PTS (Plane Transport System) was delivered to Lufthansa.

Traffic engineering - rail vehicles

The production of rail vehicles is the nucleus of Krauss-Maffei. Through the JAMaffei locomotive and machine factory. Established since 1838, locomotive construction today takes place at the Allach location in the world's oldest existing locomotive factory.

Steam locomotives were built from the start. From 1909 there were first attempts at electric locomotives for the Baden State Railways, whose electrical equipment was supplied by Siemens-Schuckert-Werke (SSW) . Diesel locomotives were also built. On April 3, 1956, the locomotive 65 018, the last steam locomotive from Krauss-Maffei, went on a test drive on the Deutsche Bundesbahn.

In the 1970s, Krauss-Maffei was also involved in the development of the Transrapid suspension railway. At that time there was an approx. 900 meter long test track for the Transrapid 02 and the Transrapid 03 on the factory premises, and from 1976 a 2400 meter long test track for the Transrapid 04 vehicle. Both routes were demolished in the early 1980s after the Transrapid project failed to achieve commercial success. In 1987 the lightweight prototype of the Transrapid-07 was produced, which was tested in 1988 in Emsland. The Transrapid-07 was the last development.

From 1985 Krauss-Maffei participated in the construction of the ICE 1 power cars .

Krauss-Maffei Verkehrstechnik GmbH was called Siemens Krauss-Maffei Lokomotiven GmbH from 1999 and has been fully integrated into Siemens AG since 2001 . In 2010, the Munich-Allach locomotive works produced around 200 locomotives individually according to customer requirements, each with a construction period of around three months. Between the construction of the Allach locomotive works in the 1920s and 2015, around 22,000 locomotives were delivered. The production figures are subject to market-related fluctuations. About 80 locomotives were manufactured in 2015.

process technology

The Krauss-Maffei product range also included centrifuges, dryers, filters and separators for the chemical, pharmaceutical, plastics, environmental, raw materials and food industries. These activities went, initially as KMV GmbH, Vierkirchen , under the name of the Andritz Group . The KMV could only use the abbreviation KM, supplemented by the V for process engineering, since the trademark rights were transferred from Krauss-Maffei AG to Krauss-Maffei Kunststofftechnik GmbH.

Automation technology

The automation technology division was responsible for automation as well as regulation and control equipment across the group. Electrical components and control cabinet construction were important for plastics technology.

Services

Krauss-Maffei AG was also rounded off by a service company that focused on IT tasks.

literature

- Alois Auer (Ed.): Krauss-Maffei. CV of a Munich factory and its workforce . Report u. Documentation by Gerald Engasser. 3K-Verlag, Kösching 1988, ISBN 3-924940-19-3 ( series of publications of the Archives of the Munich Labor Movement eV 1).

- Krauss-Maffei AG (Ed.): Krauss Maffei - 150 years of progress through technology - 1838–1988 . Hermann Merker Verlag, Fürstenfeldbruck 1988, ISBN 3-922404-07-3 .

- Wolfgang Gebhardt: German omnibuses since 1895 , Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart, ISBN 3-613-01555-2 , pp. 332-340.

- Wolfgang H. Gebhardt: German travel buses . Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-613-03037-4 , p. 131-134 .

- Ulrich Kubisch: Omnibus , Elefantan-Press-Verlag, Berlin 1986, ISBN 3-88520-215-8 , p. 106/107.

Web links

- Company website

- Karl Schmidt, Krauss-Maffei, in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

Individual evidence

- ↑ kraussmaffei.com: History

- ↑ Imprint - KraussMaffei. Retrieved April 18, 2020 .

- ↑ kraussmaffeigroup.com: The KraussMaffei Group

- ↑ k-zeitung.de: Another record result for Krauss Maffei ( memento of the original from March 22, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ NRhZ-Online : Protests against the arms company Krauss-Maffei Wegmann from September 5, 2012

- ^ Süddeutsche Zeitung : Armaments program - slaves for industry from September 2, 2015

- ^ A b c Karl Schmidt: Krauss-Maffei - 150 years of progress through technology 1838–1988 . Ed .: Krauss-Maffei AG. Hermann Merker Verlag, Fürstenfeldbruck 1988, ISBN 3-922404-07-3 , p. 130 .

- ^ Jürgen Jacobi: Omnibuses from Krauss-Maffei . In: Omnibus-Magazin , Issues 10-12, Verlag Wolfgang Zeunert, Gifhorn 1978, ISSN 0343-2882

- ^ Takeover by Onex Corporation

- ↑ KraussMaffei: Chinese state-owned company buys machine builder , Spiegel Online, January 11, 2016.

- ↑ China buys Krauss Maffei , faz.net, January 11, 2016.

- ↑ Gerhard Hegmann: KraussMaffei: Mechanical engineering company goes public in China . In: THE WORLD . December 11, 2017 ( welt.de [accessed March 4, 2020]).

- ^ A b c Peter Köhler: Foreign listing: Krauss-Maffei goes public in China. Handelsblatt, January 16, 2019, accessed on March 4, 2020 .

- ^ Heise.de: Cyber attack: KraussMaffei blackmailed by hackers

- ↑ focus.de: Cyber criminals blackmail mechanical engineering company Krauss Maffei

- ↑ Peter Königsreuther: Kraussmaffei and Netstal are bundling their competencies under the umbrella brand. Retrieved March 4, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Editor: Krauss Maffei is repositioning itself. In: Plastverarbeiter.de. Hüthig Verlag, July 3, 2019, accessed on March 4, 2020 (German).

- ↑ From: VaterstettenFM: Verkehrsprobleme? This is what the industrial park will look like. July 19, 2019, accessed on October 6, 2019 (German).

- ↑ FOCUS Online: Machine manufacturer KraussMaffei leaves Munich. Retrieved March 4, 2020 .

- ↑ Sabine Koll: Job cuts at Krauss Maffei. In: K-ZEITUNG. February 11, 2020, accessed on March 4, 2020 (German).

- ↑ Handelsblatt: Maschinenbauer: KraussMaffei cuts jobs in Germany and abroad. Retrieved March 4, 2020 .

- ↑ Florian Langenscheidt , Bernd Venohr (Hrsg.): Lexicon of German world market leaders. The premier class of German companies in words and pictures . German Standards Editions, Cologne 2010, ISBN 978-3-86936-221-2 .

- ↑ a b Alois Auer et al .: Krauss-Maffei - curriculum vitae of a Munich factory and its workforce . In: Alois Auer (Hrsg.): Series of publications of the archive of the Munich labor movement eV Volume 1 . 3K-Verlag, Kösching 1988, ISBN 3-924940-19-3 , p. 270-271 .

Coordinates: 48 ° 11 ′ 33.1 ″ N , 11 ° 28 ′ 18.6 ″ E