Luxembourg in World War II

The Second World War posed a serious threat to the Luxembourg state (see History of Luxembourg ) and resulted in national symbols such as the Luxembourg language and the monarchy becoming firmly anchored in the Luxembourg national consciousness.

The monarchy was legitimized by the referendum of September 28, 1919 (77.8 percent of Luxembourgers voted for maintaining the monarchy under the Grand Duchess Charlotte ). Charlotte had held the throne since January 15, 1919 as the successor to her sister Maria-Adelheid, who had abdicated on January 9, 1919.

On the first day of the western campaign , on May 10, 1940, Luxembourg was occupied by the German Wehrmacht . The aim of the German attack was to bypass the French defenses of the Maginot Line by advancing through the Luxembourg-Belgian area. Luxembourg was of interest as a transit country; decisive battles took place a few days later in the French Ardennes and Belgium ; the first was the battle of Sedan (10-13 May 1940) .

The order to prepare for the operation was given on October 9, 1939; the attack order was postponed 29 times. On May 10, 1940, the attack by German units ( yellow case ) with a total of seven armies on the neutral states of the Netherlands , Belgium and Luxembourg (unarmed neutrality) began.

Pre-war period

In 1867 Luxembourg declared itself neutral, and the four major European powers Great Britain, France, Prussia and Russia guaranteed the observance of neutrality in the Second London Treaty . During the First World War , neutrality was broken by the German Reich on August 2, 1914 as part of the Schlieffen Plan and Luxembourg occupied for the duration of the war in order to attack France by the neutral Benelux states, bypassing the French border fortresses. After the First World War, Luxembourg joined the Briand-Kellogg Pact in 1929 and, like the German Reich (as the first signatory in 1928), declared that it would refrain from wars of aggression and settle disputes peacefully.

As early as the time of the Weimar Republic , Luxembourg was the subject of a historically based desire for annexation, promoted by revisionist and expansionist research on the West that was oriented towards folk and cultural soil .

Even before the Second World War, there was widespread anti-Semitism in Luxembourg , which was articulated in national-populist movements, but also in Catholic-conservative circles around the daily newspaper Luxemburger Wort . For this reason, and because the government did not want to upset the powerful neighbor in the east, the entry regulations for Jewish refugees from the German Reich were tightened more and more, especially from 1936. The first Nuremberg Race Law was adopted by Luxembourg in 1935 and by other countries to the effect that Germans living in Luxembourg were prohibited from marrying Jews. Jews who fled to Luxembourg were registered separately. Jews were classified as second class people and, among other things, hindered their job search.

In the course of the anti-Jewish measures in Germany and Austria, many German and Austrian Jews fled to Luxembourg from 1938 onwards. The Luxembourg authorities began sending refugees who had been captured back to Germany. The right-wing press and the banned Luxembourg NSDAP fueled xenophobia and anti-Semitism.

eve

Due to the German attack on Poland on September 1 and the subsequent entry into the war by France on September 3, 1939, neutral Luxembourg found itself between the fronts without its own armed forces. While the sympathy of the population lay with the Allies, the government was forced to pursue a conscientiously neutral policy because of Luxembourg's neutrality. In this way she hoped to avert an attack by the German Wehrmacht . From September 1, 1939, Radio Luxemburg stopped broadcasting. In the spring of 1940 barricades were erected along the German-Luxembourg and also along the Luxembourg-French border, the so-called Schuster Line . It was named after the construction manager Schuster and essentially consisted of steel gates on heavy concrete blocks, which were supposed to make the advance across the street more difficult. In view of the overwhelming power of the enemy, the shoemaker line had a more symbolic character and served mainly to calm the population. Luxembourg did not have an army or an air force because of its unarmed neutrality , only a small volunteer corps .

After several false alarms in the spring of 1940, the certainty increased that there would be a military conflict between France and Germany. In order to hinder steel exports from the Luxembourg steelworks to Belgium and Great Britain, Germany stopped deliveries of coke to Luxembourg. It tried to force Luxembourg to adopt a pro-Germany stance, which put the Luxembourg government in a difficult diplomatic position. At the time, it was not foreseeable whether Germany would occupy Luxembourg and then annex it.

Invasion of the Wehrmacht

On May 10, 1940 at 3.15 a.m., the steel doors on the border were closed due to the increasing number of events and troop movements on the German side of the Moselle and Our . Plainclothes details from Germany, supported by the "shock troops Lützelburg", a group of residents in Luxembourg Reich Germans , already occurred previously in action. Their task was to prevent the bridges on the border from being blown up, to block the steel doors and to prevent radio communications. However, the execution of these tasks largely failed. The grand ducal family moved from their residence at Berg Castle to the grand ducal palace in the capital.

German troops invaded Luxembourg from 4.35 a.m. They did not encounter any significant resistance as the volunteer company had stayed in the barracks . Due to the enormous military inferiority, it could not have done anything anyway. The capital was occupied in the early hours of the morning.

The counter-attack by France took place around 8 a.m. Parts of the third French light cavalry division (3 DLC) of General Petiet amplified by the first Spahis brigade Supreme Jouffrault and the second company of the fifth battle tank battalion (5 BCC), is exceeded in the southern Minette the limit retreated after short skirmish but again behind the Maginot Line . Except for the south of the country, all of Luxembourg was occupied on the evening of May 10th.

The advance of the German troops prompted the authorities to evacuate the population of the canton of Esch-Alzette (approx. 90,000): 47,000 people were evacuated to France, 45,000 to the center of the country and to the north.

The Grand Duchess and the government (with the exception of Nicolas Margue ) fled to Portugal via France and later to Great Britain . Only the Secretary General of the Government Albert Wehrer , at the head of a government commission, and the 41 MPs remained behind.

Occupation policy of the German Reich

The German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop assured the Luxembourgers on the day of the invasion that territorial and political independence would not be affected. From May 10 to August 2, Luxembourg was under German military administration. On May 17, 1940, the Volksdeutsche movement was founded in Luxembourg City . Its chairman was Damian Kratzenberg and its main task was to use propaganda to bring the Luxembourgers to a Germany-friendly attitude in order to lead them " home into the Reich ".

As early as July 29, 1940, Luxembourg was declared a CdZ area of Luxembourg . Head of Civil Administration were Gustav Simon and his deputy Heinrich Christian Siekmeier . Luxembourg was to be incorporated into the German Empire, since, according to the German Interior Ministry, the Luxembourgers were only to be regarded as another tribe of the Germanic people and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg was thus to be regarded as a Germanic tribal area. Simon was the head of the Trier-Koblenz Gau (later Moselland) and, as Gauleiter, was under Adolf Hitler's sole responsibility .

The policy of the German Reich had two clear goals:

- the Germanization of Luxembourg , d. H. the eradication of everything different or "non-German" such as words and names of French origin

- the dissolution of the Luxembourg state.

Simon's first official acts, a list of ordinances, made these goals clear:

- August 6, 1940: The use of the French language is banned. The ban included not only street and place names, but also expressions of everyday use such as “Bonjour”, “Merci”, “Monsieur”, “Madame” etc., as well as names of shops. French first names and surnames are replaced by German ones. For example, Henri becomes Heinrich , Dupont becomes Brückner .

- Autumn 1940: The political parties as well as the Chamber of Deputies and the Council of State are dissolved.

- October 4, 1940: All streets in Luxembourg City are renamed, for example Avenue de la Liberté to Adolf-Hitler-Strasse .

- By the end of 1940: German jurisprudence including the special courts and Nuremberg laws are introduced. The German court organization is also introduced.

- The Luxembourg press is placed under the total control of the Gauleiter.

These measures were accompanied by massive propaganda and harassment or intimidation of dissidents or opposition members, as well as officials and functionaries in particular. People who held positions of responsibility in public life and in the economy were subjected to severe pressure, while a central card file documented the personal attitude of every Luxembourger to the Nazi regime. Anyone who resisted was removed from office or relocated to Germany, mainly to East Germany. “Serious” cases were interned in concentration camps, where many of them perished.

Persecution of the Jews

At the time of the German attack on May 10, 1940, there were around 3700 Jews in Luxembourg. Three years later, in June 1943, there were only 20 to 30 Jews (mostly living in " mixed marriages "). Over half of the Jewish population had left the country for France in May 1940. In the first months of the occupation, when Luxembourg was under military administration, the Jewish population was not treated separately. However, this changed with the civil administration from the end of July 1940. One of the priorities of the head of the civil administration, Gustav Simon, was to introduce Germany's discriminatory legislation in Luxembourg. From September 5, 1940, the provisions of the Nuremberg Laws also applied to Jews residing in Luxembourg. 350 Jewish companies were Aryanized , the property of the Jews confiscated and forced labor for Jews introduced. In 1941 the synagogues in Luxembourg City and Esch were destroyed. The “Ordinance concerning the order of Jewish life in Luxembourg” of July 29, 1941 not only excluded Jews from any social life (e.g. by prohibiting them from participating in public events), but also introduced one earlier than in Germany yellow marking (armband) to be worn on clothing.

After a threatened mass deportation was prevented in September 1940, around 1450 Jews were able to emigrate in collective transports, mostly accompanied by the Gestapo, by the end of 1941. Many were stranded in the French internment camps at Gurs and Les Milles . When the German authorities announced a ban on emigration in October 1941, around 700 Jews of different nationalities were still living in Luxembourg. The disabled people were gradually concentrated in the so-called Jewish old people's home in Fünfbrunnen - near a railway line.

The 331 Jews from Luxembourg deported to Lodz on October 16, 1941 were the first to be deported to Eastern Europe from an occupied Western European country. Only 43 of the 683 deported Jews (6.5%) survived the German camps. Overall, it is assumed that more than a third of the Jews living in Luxembourg in 1940 were murdered. The attitude of most Luxembourgers, which quickly turned into largely open opposition to the occupiers, was passive towards the fate of the Jews.

A minority of Luxembourg National Socialists participated in attacks against the Jewish population. B. the devastation of the Ettelbrück synagogue on October 22, 1940.

The Grand Rabbi Robert Serebrenik helped many Jews to escape and fled himself in 1941.

Terror regime

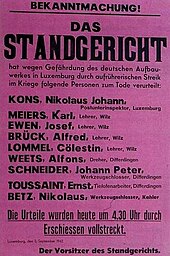

In view of the reactions from the population, the regime felt compelled to act with extreme brutality against any form of resistance. After the Night and the Fog Decree , people suspected of the resistance were deported to Germany without a trace as a deterrent. After the general strike of 1942, Simon imposed a state of emergency over the whole of Luxembourg and set up a court martial . Thousands have been arrested and tortured. Hundreds died in the concentration camps. Whole families were resettled, preferably to Silesia . German families from South Tyrol and Southeast Europe took their place . The Villa Pauly , which served as the Gestapo headquarters in Luxembourg, became a symbol of Nazi terror . On January 30, 1945, shortly before the liberation by the Red Army, 91 Luxembourgers (mostly forced recruits ) were also murdered in an end- stage crime in the Sonnenburg prison .

collaboration

Luxembourg has been criticized by international historians for the fact that no objective processing of its history has taken place during the persecution of the Jews and that Luxembourg has so far falsely portrayed itself as a victim.

The subsequent research reports by the Luxembourg historians Denis Scuto and Vincent Artuso showed that the Luxembourg Administrative Commission, which acted as a substitute government after the official government of Luxembourg went into exile, was actively involved in the deportation of the Jews. She not only collaborated with the Germans, but actively extradited Jews, including many Jewish children, to the Germans of her own accord. She acted actively and not only as a recipient of orders for the German occupiers.

Other historians around Charles Barthel criticize this view sharply. You accuse the research report of "inadequate scientific and methodological rigor" and a subjective, politically motivated judgment. The administrative commission was therefore not actively guilty of the persecution of the Jews or any other collaboration.

To date, Luxembourg has not apologized for collaborating or actively persecuting Jews, nor for expropriating Jews for the benefit of Luxembourg citizens. To this day, Luxembourg has not returned the expropriated property, real estate or companies, or given any compensation or financial reparation. There was hardly any denazification in Luxembourg either.

After the war, the Luxembourg courts carried out a total of 9,546 criminal investigations against collaborators. Judgments were made in 5,242 cases, including 2,275 convictions. The courts then passed twelve death sentences, eight of which were carried out.

Government in exile

The Grand Duchess Charlotte and members of the Conservative government, namely Prime Minister Pierre Dupong and the Minister of Transport and Justice Victor Bodson , fled to Montreal and the Ministers Joseph Bech and Pierre Krier to London. London became the official seat of the government in exile. This organized regular BBC broadcasts for Luxembourg. A small contingent of volunteers was set up as the La Luxembourg battery (also: Brigade Piron ) and took part in Allied war missions until the end. A customs treaty with the Benelux countries of Belgium and the Netherlands was concluded for the period after the war and negotiations were conducted with the Allies on the treatment of war crimes and the post-war order in Luxembourg. Luxembourg became a founding member of the United Nations War Crimes Commission , a commission to collect evidence and prepare the criminal prosecution of war crimes committed by the Axis powers. With the Luxembourg Gray Book an attempt was made to bring the situation in occupied Luxembourg closer to the Allies.

The response of the population

The population's reaction was sluggish at first, as they were still under the shock of the German invasion from 1914 to 1918 and felt abandoned by the government who had fled into exile and the grand ducal family. The different reactions of the population at the time can be broken down as follows:

Collaborators

A section of the population, mainly from the people's German movement , not only welcomed the invasion of the Germans, but was also actively involved in the destruction of the Luxembourg state. They were, so to speak, collaborators out of conviction and were called " Gielemännercher " (German: yellow man ) because of their khaki uniform . Their behavior was viewed as treason. They were joined by those who participated out of opportunism or gave in to external pressure.

Active resisters

The Luxembourg resistance relied on only a small part of the population. It also came about spontaneously and at first rather slowly. The first groups formed in 1940/1941. They worked without coordination and for different reasons, mostly for Christian, liberal and patriotic reasons:

- LPL, Lëtzeburger Patriote Liga (German: Luxemburger Patriotenliga), founded in 1940;

- LFB, Lëtzeburger Freihétsbewegungong (German: Luxembourg freedom movement), founded in 1940;

- LFK, Lëtzeburger Freihét fighter (German: Luxembourg freedom fighter), founded in January 1941;

- LVL, Lëtzeburger Volleks Legio'n (German: Luxembourg People's Legion ), founded in June 1941;

- LRL, Lëtzeburger Ro'de Lé'w (German: Luxembourg Red Lion), founded October 1941:

- PI-Men, Patriotes Indépendants (German: Independent Patriots), founded in 1941:

- LFB, Lëtzeburger Freihétsbond (German: Luxemburger Freiheitsbund);

- Alweraje , founded in 1941.

The banned Communist Party of Luxembourg also joined the resistance. It was not until March 1944 that most of the resistance groups joined together in a union of resistance groups. The actions were mainly limited to psychological warfare and less to armed resistance. Many young Luxembourgers joined the French and Belgian underground movements. The main merit of the movements, which should not be underestimated, was the moral support of the population, for example by distributing leaflets or wall graffiti, but also by hiding conscientious objectors and other persecuted people.

Majority of the population

In view of the brutality of the regime, the majority of the population renounced resistance, but did not completely hide their disapproval and disapproval of the occupiers. This was mainly expressed in smaller, subtle taunts, but also in large actions:

- During the imposing march of the German police forces in Luxembourg on August 6, 1940, many Luxembourgers wore a spindle with the red lion on its collar. This spindle came from the country’s centenary independence celebrations a year earlier. Thugs then beat up the porters.

- On October 21, 1940, the French war memorial for the fallen Luxembourg soldiers in World War I , the " Gëlle Fra ", was demolished in the capital . This happened in protest of hundreds of people who were brutally dispersed by the Gestapo . 13 people were arrested. It was the first appearance of the Gestapo in Luxembourg.

- On October 10, 1941, the head of the civil administration, Simon, wanted to have a civil status survey carried out. For three questions on 'nationality', 'mother tongue' and 'ethnicity', Luxembourgers should answer "German" and not "Luxembourgish". Samples carried out a few days beforehand showed that over 95% of those questioned had not followed this instruction. This event was quickly hyped up to a referendum, "where 'd'Letzebuerger vollek (...) the price en énegt Nen gesôt hat". Paul Dostert has convincingly demonstrated why the word 'referendum' makes sense for propaganda purposes but is analytically wrong.

- After the introduction of the Reich Labor Service and the illegal military service for the forced recruits for those born between 1920 and 1927, strikes began on August 31, 1942. The starting point was work stoppages in the factory of IDEAL Lederwerke AG , Wilz, which spread to the rest of the country. The Nazi regime reacted with extreme brutality. 20 strikers were shot in the forest at the Hinzert concentration camp , and Hans Adam of German descent was beheaded by guillotine on September 11, 1942 in Cologne. 125 arrested were transferred to the Gestapo and taken to concentration camps. Many more civilians were arrested and interrogated by the Gestapo. Teachers were arrested in Echternach and Esch-sur-Alzette . One teacher was among those sentenced to death, seven others were deported to concentration camps. A total of 290 schoolchildren, 40 apprentices from the smelting works and seven young postal workers were deported to re-education camps of the Hitler Youth, for example to Stahleck Castle . The strike also received a lot of attention abroad.

- About 40% of the forced recruits went into hiding. About half in the country itself, the rest fled abroad. Those who made it to England joined the Allies. For example, they later took part as a battalion within the Belgian Brigade Piron (other name: La Luxembourg battery) in the Normandy landings and the liberation of Brussels, as well as in other battles.

The Liberation

In September 1944, Luxembourg was liberated by the US Army . On September 10, US soldiers occupied the capital. The German soldiers withdrew from the country without fighting.

The Western Allies landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944 (" D-Day ") . After Paris surrendered almost without a fight (August 25, 1944), the Allies advanced very quickly north-east; a milestone was the Mons cauldron (September 2, 1944). From September 3, the 1st US Army swung east with the aim of capturing crossings over the Moselle and closing the gap between it and the 3rd US Army . They progressed almost without a fight. A problem these days was a lack of fuel (see also Red Ball Express ).

During the Ardennes offensive in December 1944, the north of Luxembourg ( Ösling and the region around Echternach ) was again occupied by the Germans. In January 1945 the country was liberated for the second time by US troops. The destruction as a result of the fighting was enormous.

Grand Duchess Charlotte and Prince Félix officially bid farewell to the Piron Brigade (La Luxembourg battery) on June 29, 1945 in the streets of the capital ( demobilization ), recognizing their important contribution to the liberation of the country and Europe.

War record

A total of 5,703 residents of Luxembourg died during the Second World War. This corresponds to 1.9% of the population at that time (290,000). Luxembourg thus suffered the second highest number of victims in Western Europe in relation to the number of inhabitants. According to groups:

- Of the 10,211 forcibly recruited Luxembourgers born between 1920 and 1927, 2,848 (28%) died, 96 of them are still missing . This is also relevant from a demographic point of view, as these were young men who could no longer contribute to population growth.

- Around 600 people died as a result of acts of war, especially during the Battle of the Bulge.

- 3,963 people were detained in concentration camps or prisons. 791 of them died.

- 3,614 young girls were drafted into the Reich Labor Service . 56 of them died, 2 are still missing.

- 4,186 people were deported to Luxembourg in the resettlement campaign . 154 of them died.

- 584 volunteers, 57 of whom died, served in Allied armies.

- Around 2,500 of the 3,500 Jews living in Luxembourg (the majority of whom were Jewish refugees from the German Reich) were able to flee. In 1941 around 800 Jews were still living in Luxembourg, almost all of whom were murdered.

- 640 people lost their jobs for political reasons.

- About a third of the houses were damaged by acts of war.

4,400 Luxembourgers were honored with the title "mort pour la patrie" (German: died for their homeland). Among them 2,848 deceased forced recruits, around 600 people who died as a result of acts of war and around 800 who died in camps or prisons. 324 people were denied the title of "mort pour la patrie" because anti-patriotic behavior could be proven.

Work-up

Legal processing

In view of the atrocities in the countries occupied by the Axis powers Germany, Japan and Italy, the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC) was set up on the initiative of nine London governments in exile in 1943 . The task consisted of preserving evidence, compiling lists of perpetrators, reports to the governments and preparing criminal proceedings for war crimes . The threat of punishment was intended to deter potential perpetrators from further acts. In the London Statute of August 8, 1945, the crimes for the Nuremberg Trial of the Major War Criminals were grouped into main categories:

- Crimes against peace (Art. 6a) by planning and conducting a war of aggression (contrary to the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1929)

- War crimes (Art. 6b): murder, mistreatment, deportations for slave labor of civilians and prisoners of war as well as looting and destruction without military necessity

- Crimes against humanity Art. 6c: murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation or other inhumane acts for political, racial or religious reasons

At the Nuremberg trial, the occupation of Luxembourg was viewed as a criminal war of aggression and the main culprits of the atrocities resulting from it were convicted. The Luxembourg judiciary opened court proceedings against 162 Reich Germans and there were 44 death sentences, 15 acquittals and 103 closings. Simon escaped prosecution in Luxembourg by suicide in 1945 and Siekmeier was sentenced to seven years in prison. In 5,242 Luxembourg courts delivered judgments on collaboration cases, including 12 death sentences.

Commemoration

The Mémorial de la Déportation has been set up in the former Hollerich train station since 1996. There, the deportation of Jews, forced recruits, forced resettlers and resistance workers is remembered.

literature

- Jul Christophory: Radioscopy de la littérature luxembourgeoise sur la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Luxembourg 1987.

- Michael Eberlein, Norbert Haase (ed. And edit.): Luxembourg forced recruits in the Torgau Wehrmacht prison - Fort Zinna 1943–1945 (Testimonials - Paths of suffering. Book 1). Saxon Memorials Foundation in memory of the victims of political tyranny, Dresden 1996 ISBN 3-9805527-0-5 .

- René Fisch: The Luxembourg Church in World War II. Documents, certificates, pictures of life. Luxembourg 1991.

- Club des Jeunes ELL: Lëtzebuerger am Krich 1940–1945: narrow kleng Natioun achieved. Club des jeunes, Luxembourg 2001, ISBN 2-9599925-1-2 .

- Club des Jeunes ELL: D'Krichjoeren 1940-45 zu Lëtzebuerg. Wéi closely youth de Krich huet erlieft. Club des Jeunes ELL, 1997 ISBN 2-9599925-0-4 .

- Even Georges: Krichserliefnisser 1940–1945. Luxembourg witnesses tell. Editions Guy Binsfeld, 2003, ISBN 2-87954-128-X .

- Even Georges: Deemools am Krich 1940-1945. Fates in Luxembourg. Tell people. Editions saint-paul, 2005, ISBN 2-87963-586-1 .

- Even Georges: Women experience the war. éditions saint-paul, 2007, ISBN 978-2-87963-681-8 .

- Even Georges: Ons Jongen a Meedercher. The stolen youth. Editions Saint-Paul, 2012, ISBN 978-2-87963-840-9 .

- Paul Dostert: Luxembourg between self-assertion and national self-abandonment: German occupation policy and the ethnic German movement 1940–1945. Luxembourg 1985.

- Jean Milmeister: The Battle of the Ardennes 1944-1945 in Luxembourg. Editions Saint Paul, 1994.

- Andreas Pflock: On forgotten tracks. A guide to memorials in the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. (Series: Topics and Materials). Federal Agency for Political Education, Bonn 2006, ISBN 3-89331-685-X .

- Peter M. Quadflieg : "Forced Soldiers" and "Ons Jongen". Eupen-Malmedy and Luxembourg as recruiting areas for the German Wehrmacht in World War II. Aachen 2008, ISBN 978-3-8322-7078-0 .

- Fritz Rasque: The Oesling in the war. Imprimerie St. Paul, Lëtzebuerg 1946.

- Marc Schoentgen: Between remembering and forgetting. The commemoration of the Second World War in the 50's. In: Claude WEY: Le Luxembourg des années 50. Luxembourg 1999.

- John Toland: Die Ardennenschlacht 1944 (Original title: Battle: The Story of the Bulge ) Alfred Scherz Verlag, Stuttgart 1960.

- Hans-Erich Volkmann: Luxembourg under the sign of the swastika: a political economic history 1933 to 1944 . Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, ISBN 978-3-506-77067-7 .

See also

Web links

- Detailed explanations about Luxembourg in World War II

- Memorial sites in Luxembourg

- National Military History Museum

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hans-Erich Volkmann: Luxembourg under the sign of the swastika . P. 173.

- ↑ Vincent Artuso: La "Question juive" au Luxembourg (1933–1941): L'État luxembourgeois face aux persécutions antisémites nazies (1933–1941), retrieved from: Archived copy ( Memento of the original of July 13, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ From the history of the Jewish communities in the German-speaking area - Luxembourg , accessed on December 13, 2015.

- ^ Trausch Gilbert: Le luxembourg à l'époque contemporaine, editions Bourg-Bourger, Luxembourg, 1981

- ^ Der Fenstersturz - Justiz , Spiegel 6/1965, accessed November 1, 2015

- ↑ Guy May: The street names of the city of Luxembourg under German occupation (1940–1944) ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ From the history of the Jewish communities in German-speaking countries - Luxembourg , accessed on October 29, 2015.

- ↑ The Yellow Star was decreed by the Reich Minister of the Interior from September 1, 1941 in the German Reich and in other areas occupied by Germans

- ↑ Änder High Garden: The National Socialist Jewish policy in Luxembourg. Commissioned by the Memorial de la Déportation in Luxemburg-Hollerich. 2nd, change Edition. Luxembourg 2004, p. 44 ff.

- ↑ Änder High Garden: The National Socialist Jewish policy in Luxembourg. , P. 50 ff.

- ↑ Exhibition Between Shade and Darkness - Le sort des Juifs du Luxembourg de 1940 à 1945. ( Memento of the original from June 24, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Musée national de la Résistance, Esch-sur-Alzette , May 29–24. November 2013.

- ↑ Sonnenburg massacre - mass murder still deep in the memory after 70 years , Luxemburger Wort, January 30, 2015, accessed October 27, 2015

- ^ The "Jewish question" in Luxembourg: milestone or stumbling block? In: Wort.lu. October 9, 2015, accessed May 20, 2016 .

- ↑ tageblatt.lu: Systematic persecution of Jews , accessed on February 17, 2015

- ↑ volksfreund.de: The ugly side of the story , accessed on February 17, 2015

- ↑ wort.lu: dealing with national history. The myth is crumbling. , accessed February 17, 2015

- ↑ wort.lu: Vincent Artuso. "It was a great moment," accessed February 17, 2015

- ↑ wort.lu: We are not heroes , accessed on February 17, 2015

- ↑ wort.lu: reaction to Artuso report. "Nobody should be denounced" , accessed on February 17, 2015

- ↑ wort.lu: List of 280 Jewish children given to Nazi occupiers , accessed on February 17, 2015

- ↑ tageblatt.lu: Why did Luxembourg collaborate? , accessed February 17, 2015

- ↑ tageblatt.lu: Systematic persecution of Jews , accessed on February 17, 2015

- ↑ wort.lu: Historians examine Luxembourg complicity in the deportation of Jews , accessed on February 17, 2015

- ↑ wort.lu: Paul Dostert: Denis Scuto rushes too fast , accessed on February 17, 2015

- ↑ Archived copy ( memento of the original from November 20, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. 480 names for the Gestapo

- ^ Krier Emile: Luxembourg at the end of the occupation and the new beginning . Archived copy ( memento of the original dated November 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Eliezer Yapou: Governments in Exile, Luxembourg , accessed on 10 December 2015

- ↑ Paul Dostert: Luxemburg: Resistance during the German occupation 1940-45 , published in: Handbook on Resistance to National Socialism and Fascism in Europe 1933/39 to 1945 , Ed. Gerd R. Ueberschär, De Gruyter, 2011, ISBN 978-3- 598-11767-1 , p. 137 ff.

- ↑ Paul Dostert: Luxembourg between self-assertion and national self-abandonment. Luxemburg 1985, pp. 154-155.

- ^ Word on the general strike ( Memento of the original from July 12, 2007) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 366 kB), source: LW / NiM (accessed April 15, 2011)

- ↑ Chapter XXXII: Towards the Heart of Germany , page 692

- ↑ therein picture: Public demobilization by the Grand Duchess in the streets of Luxembourg , Luxemburger Wort , September 15, 2014, text in French.

- ^ Michel Pauly: History of Luxembourg . CH Beck 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-62225-0 , p. 102

- ^ Luxembourg . United States Holocaust Memorial Museum . Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ↑ Livre d'or des victimes de guerre de 1940 à 1945, publié par le Ministère de l'Intérieur

- ^ Statute for the International Military Tribunal of August 8, 1945 (PDF)

- ↑ Emile Krier: Luxembourg at the end of the occupation and the new beginning ( memento of the original from November 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Regionalgeschichte.net, accessed November 2, 2015

- ^ Deportation memorial : Hollerich station , Gedenken in Benelux, accessed August 29, 2016