Missa solemnis (Beethoven)

The Missa solemnis in D major , op. 123, composed by Ludwig van Beethoven between 1819 and 1823 , is considered to be one of the composer's most important achievements and is one of the most famous masses of occidental art music . Formally, the work belongs to the type of Missa solemnis .

classification

Beethoven himself described it as his most successful work in the last years of his life, and although its popularity does not match many of his symphonies and sonatas , it shows Beethoven at the height of his creative powers. It is his second mass after the lesser known Mass in C major, op.86 from 1807.

Emergence

The composition of the Missa solemnis goes back to Beethoven's friendship with Archduke Rudolph of Austria (1788–1831). The Archduke was a very talented student of the composer in piano playing and composition; as well as a sponsor of Beethoven in material terms. Therefore Beethoven dedicated several of his most important compositions to his friend, including the opera Fidelio . On the occasion of the enthronement of the Archduke as Archbishop of Olomouc on March 9, 1820, Beethoven planned the composition of a mass. An entry in Beethoven's diary from 1818 suggests that Beethoven had plans to compose a mass even before the specific occasion of the enthronement: »To write true church music, go through all the church choirs of the monks etc. [,] where to look [, ] like the paragraphs in the most correct translations together with perfect prosody of all Christian Catholic psalms and chants in general. " This assumption is supported by a six-page manuscript of the ordinarium text prepared by Beethoven, including stress marks and a German translation.

When Beethoven received the news of Rudolph's appointment as Archbishop of Olomouc , he wrote: “The day when a high mass of mine is to be performed for the celebrations for HRH will be the most beautiful of my life for me; and God will enlighten me that my weak powers will contribute to the glorification of this solemn day. "

However, the episcopal ordination in Olomouc took place without the performance of the mass, as the dimensions of the planned mass grew far beyond the usual framework and became Beethoven's more than four-year search for his understanding of God. The musician operational intensive research in the fields of theology , liturgy and the history of sacred music , from the time of origin of Gregorian chant about Palestrina to Bach and Handel . Beethoven wrote the mass in Mödling in his summer house there, which is now a Beethoven memorial.

Beethoven preferred working on the Missa solemnis to other projects. For example, the composition of the Requiem that Beethoven had planned and that he had promised to the cloth merchant Johann Wolfmayer in the spring of 1818 did not materialize; he had promised a fee of 450 guilders. The composition of an oratorio Victory of the Cross over the legend of the victory of Constantine the Great in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge failed after librettist Joseph Carl Bernard initially delivered the text for the oratorio late and the text was then submitted by both Beethoven and the management of the Gesellschaft für Musikfreunde, from which the initiative for the oratorio originated, was found to be unsuitable.

As the sketchbooks for the Missa solemnis show - for no other work by Beethoven have so many sketchbooks survived as for the Missa solemnis - the Kyrie , the Gloria and the Credo were created between April 1819 and July 1820, i.e. the period when Archduke Rudolph was enthroned . While negotiating with interested publishers and assuring them that the mass composition would be completed soon, he first composed the piano sonatas No. 30 (op.109) and No. 31 (op.110) and then from November 1820 to July 1821 he composed the Sanctus (with Benedictus ) and the first two parts of Agnus Dei . In a third working phase from April to August 1822, Beethoven wrote the Dona nobis pacem ; By November 1822, Beethoven undertook revisions to the entire score.

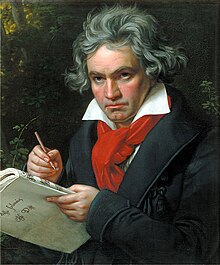

From February 11th to April 10th, 1820, Beethoven sat the painter Joseph Karl Stieler as a model for a portrait in a total of four sessions, which shows him composing the Missa solemnis ; Beethoven, who otherwise did not like being portrayed, did so in this case Friendship with Franz and Antonie Brentano , who wanted a Beethoven portrait "painted life-size by Stieler," as an unknown interlocutor of the composer wrote in his conversation book. The picture was first exhibited in Vienna at the spring exhibition of the Vienna Art Academy in 1820; a little later Stieler became an honorary member of the academy.

For Beethoven, the composition of the Missa solemnis was also associated with hopes of becoming his conductor after the archduke's enthronement. The first hopes in this regard were dashed in 1811 when Archduke Rudolph could have been enthroned after the death of Archduke Hieronymus von Colloredo , but declared that he would not. But even in 1820 there was no appointment as Kapellmeister after Archbishop Rudolph's requested delivery of the Missa solemnis failed.

Premieres

Beethoven presented his friend, the Cardinal and Archbishop of Olomouc, with the Missa solemnis dedicated to him on March 19, 1823 (the composer mistook this date for the anniversary of the enthronement). The archbishop received the dedication score written by a copyist, while a working score remained with Beethoven for further revisions of the musical text and as a basis for the engraving. Archbishop Rudolph noted in his "Musikalien-Register" that "this beautifully written MS [...] was given to him by the composer himself on March 19, 1823" .

The dedication inscription "From the heart - May it go back to the heart" can be found neither in the dedication score presented to the archbishop nor in the first print, but only in the autograph kept in the Berlin State Library. Beethoven may have distanced himself from this dedication to the archbishop after the relationship between the two men had cooled down.

Beethoven initially sold handwritten copies of the Missa solemnis to aristocratic subscribers and assured them that he would not have the mass printed for the time being. Despite this promise, he negotiated with up to seven publishers at the same time and received advances without being able to provide corresponding consideration. It was first published shortly after Beethoven's death in April 1827 by Schott Verlag in Mainz .

The first performance did not take place in a sacred setting, but at the Philharmonic Society in Saint Petersburg on the initiative of the Russian nobleman and patron Nikolai Borissowitsch Golitsyn on April 7, 1824 (according to the Julian calendar still valid in Russia on March 26). The premiere, originally planned for Christmas 1823, was delayed due to the rehearsal of the demanding choral parts, which turned out to be more time-consuming than planned, as well as incorrectly copied parts. Who directed the premiere on April 7, 1824 is unknown.

Parts of the mass ( Kyrie , Credo , Agnus Dei ) were heard on May 7, 1824 under the direction of Kapellmeister Michael Umlauf at the kk Kärntnertortheater in Vienna together with the overture to The Consecration of the House and the 9th Symphony . The three movements of the mass listed were declared as “hymns”, since the secular, i.e. non-church performance of mass settings was forbidden by the Vienna censorship authority.

Another performance of the entire mass took place in 1830 in the church of St. Peter and Paul in the Bohemian town of Warnsdorf in a liturgical setting.

music

occupation

- Classical symphonic orchestra with trombones and contrabassoon (2, 2, 2, 2 - 4, 2, 3, 0, timp, str)

- Mixed choir of four voices

- Four vocal soloists ( soprano , alto , tenor , bass )

- Organ (with pedal )

Duration

The performance lasts about an hour and a quarter (70–80 minutes).

structure

Like most masses, the Missa solemnis is divided into five movements :

- Kyrie

- Gloria: Gloria in excelsis deodorant. Qui tollis. Quoniam tu solus sanctus.

- Credo: Credo in unum Deum. Et incarnatus est. Et resurrexit.

- Sanctus: Sanctus. Benedictus.

- Agnus Dei: Agnus Dei. Vb Dona nobis pacem.

- Kyrie : As the most traditional section, the Kyrie has the classic ABA 'structure. Sustained chorale passages at the beginning of the Christe eleison mergeinto a more contrapuntal part in which the four vocal soloists are introducedat the same time.

- Gloria : Rapidly varying textures and themes raise at the beginning of this sentence, which in an exemplary manner in nigh odd tempo is set, every single line of the Gloria forth. The movement ends with the first of the two broad fugues in the work on the lines of text In Gloria dei patris. Amen , which lead to a recapitulating increased variation of the first part.

- Credo : This movement, which is one of the most remarkable pieces of music from Beethoven's pen, begins with a chord sequence that appears again later and is modulated . Melancholy modal harmonies for the Incarnatus soft in Crucifixus always expressive increases to the remarkable, a cappella set et resurrexit , which then ends abruptly. The most extraordinary part of this movement is the fugue on Et vitam venturi saeculi towards the end, which contains some of the most difficult to sing passages in all of choral literature , especially in the furious double-tempo finale.

- Sanctus : Up to the Benedictus des Sanctus, the Missa solemnis correspondsapproximately to classical conventions. Here, however, after an orchestral “preludio”, the solo violin joins in at the highest pitch. It symbolizes the Holy Spirit, who descends to earth in the Incarnation of Christ, and introduces the most moving passages of the entire work.

- Agnus Dei : The pleading Miserere nobis of the male voices at the entrance leads to the radiant peace prayer Dona nobis pacem in D major. After a fugal development it is interrupted by confusing, warlike sounds, while the end sounds more peaceful again. Beethoven quotes, among other things, the theme from Handel's Messiah “And he reigns forever and ever” ( Hallelujah , chorus).

reception

At the Vienna partial performance of the mass on May 7, 1824, it was overshadowed by the success of the 9th Symphony . For example, while music critic Joseph Carl Bernard described the symphony as “non plus ultra”, he was more reserved about the mass sentences. In the Credo, "both the basic key, B flat major, and the time measure [...] have been changed too often". At the Agnus Dei he lamented unconventionality as an end in itself. Bernard denied the choir complete confidence in intonation and nuanced performance.

The allegation of innovation for the sake of innovation was taken up after a performance of Kyrie and Gloria at the Niederrheinischen Musikfest in Krefeld in 1827 by the "Rheinischer Merkur" who wrote:

“The first movement, the Kyrie, is very beautiful [...] and this first part really belongs to the most excellent that the newer compositions in this genre have produced. The Gloria is only partially comprehensible, sometimes only bar by bar, like sparks of light individual bars emerge from the deepest darkness, but immediately disappear again in front of an immense mass of instrumental figures and immediately successive, very different chords, so that with the very rapid movement a finding and Following any melodic course is almost impossible [...] The Gloria suddenly breaks off with very short notes and closes. This particularly weakened the impression "

A performance of Sanctus with Benedictus at its Vienna premiere in 1883 as part of a subscription concert in the Kärntnertortheater met with similar reservations about the unusual .

Especially after Beethoven's death, a conflict developed between the reservations about the Missa solemnis on the one hand and the scruples about criticizing the work of a composer of Beethoven's rank on the other. For example, the “ Allgemeine Musikische Zeitung ” wrote that the Gloria was “almost as difficult to perform and understand as all of its recent art epochs. Anyone who presumes to have grasped and understood such a complex tonal work after hearing it once may dare to make a judgment about it. Ref. Avows incapable of doing so "

A debate arose between supporters and critics of the Missa solemnis. The criticism culminated, among other things, in an article by Ernst Woldemar (pseudonym for Heinrich Herrmann), published in 1828 in the “Caecilia”, in which the latter criticized Beethoven's late works as a whole, about "men of special understanding, regulated imagination and healthy ears, in silence have shaken their heads not a little ”. He attributed this circumstance to Beethoven's deafness and declared that after Beethoven's death there was no need to stop him from “piety” from declaring out loud at every opportunity that he [...] had the unhappy, melancholy, gloomy and confused brooding which he distinguished Head hatched shortly before his death, can not only acquire the slightest taste, but that even when hearing them he does not feel any different than if he were in an asylum, and that he is still very frightening, tasteless and must find it appalling ”.

Woldemar's position was criticized by the Leipzig organist Carl Ferdinand Becker , who said that understanding Beethoven's works was reserved for later generations. In the years after Beethoven's death, the Würzburg music pedagogue and university professor Franz Joseph Fröhlich was the only one who analyzed the aim of the conception of the Missa solemnis in 1828 and recognized that the work should be performed outside of a liturgical framework.

literature

- Sven Hiemke: Ludwig van Beethoven. Missa solemnis. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003, ISBN 3-7618-1516-6 .

- Missa solemnis op. 123 , in: Sven Hiemke (ed.): Beethoven-Handbuch. Bärenreiter, Kassel, 2009, ISBN 978-3-7618-2020-9 , pp. 310-317

- Heavenly and earthly - The Missa solemnis , in: Lewis Lockwood : Beethoven: His music - His life. , Metzler, 2009, ISBN 978-3476022318 , pp. 312-321

- The Missa solemnis, a mass for peace , in: Jan Caeyers: Beethoven: The lonely revolutionary - A biography , CH Beck, anniversary edition 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-65625-5 , pp. 622–639

- Wolfgang Rathert : The fairs. In: Birgit Lodes , Armin Raab (eds.): Beethoven's vocal music and stage works. Laaber, Laaber 2014, ISBN 978-3-89007-474-0 ( Beethoven manual. Volume 4).

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Missa solemnis op.123 , full score. Ed. And with a foreword by Ernst Herttrich. Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISMN M-007-09603-8

Web links

- Missa solemnis, op. 123 : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Audio samples

- 'Missa Solemnis,' a Divine Bit of Beethoven - National Public Radio on Beethoven's Missa solemnis (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Maynard Solomon : Beethoven's diary , ed. by Sieghard Brandenburg , Mainz 1990, p. 121

- ^ Beethovenhaus , accessed on February 10, 2016

- ↑ Ludwig van Beethoven: Konversationshefte , ed. On behalf of the German State Library. by Karl-Heinz-Köhler, Dagmar Beck and Grita Herre with the participation of Günter Brosche, Ignaz Weinmann, Peter Pötschner and Heinz Schöny, 11 volumes, Leipzig 1968–2001, volume 1, p. 196 (entry between January 11th and 17th 1820)

- ↑ Ludwig van Beethoven: Konversationshefte , ed. On behalf of the German State Library. by Karl-Heinz-Köhler, Dagmar Beck and Grita Herre with the participation of Günter Brosche, Ignaz Weinmann, Peter Pötschner and Heinz Schöny, 11 volumes, Leipzig 1968–2001, volume 1, p. 268 (entry between February 22, 1820)

- ↑ quoted from: The work of Beethoven. Thematic-bibliographical index of all his completed compositions , ed. by Georg Kinsky and Hans Halm, Munich and Duisburg 1955, p. 363

- ↑ Birgit Lodes: "From the heart - May it go to the heart again!" On the dedication of Beethoven's Missa solemnis , in: Old in New. Festschrift Theodor Göllner on his 65th birthday , ed. by Bernd Edelmann and Manfred Hermann Schmid ( Munich publications on music history , Volume 51), Tutzing 1995, 295ff.

- ↑ Sven Hiemke: Ludwig van Beethoven. Missa solemnis. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2003, pp. 130ff.

- ↑ Cf. Golizyn an Beethoven, March 2, 1824 (Ludwig van Beethoven: Briefwechsel. Complete edition , on behalf of the Beethoven-Haus Bonn, edited by Sieghard Brandenburg , 6 volumes and a register volume, Munich, 1996–1998, volume 5, p . 234)

- ^ Rainer Lepuschitz: Introduction to the concert of the Tonkünstler-Orchester Niederösterreich , October 2007

- ↑ Joseph Carl Bernard : News , in: Allgemeine Musikische Zeitung 26 (1824), No. 27 issue from July 1st, Col. 436ff .; quoted from: Ludwig van Beethoven. The work in the mirror of its time. Collected concert reports and reviews up to 1830 , ed. and introduced by Stefan Kunze in collaboration with Theodor Schmid, Andreas Traub and Gerda Burkhard, Laaber 1987, p. 473

- ↑ Joseph Carl Bernard: News , in: Allgemeine Musikische Zeitung 26 (1824), No. 27 issue from July 1st, Col. 436ff .; quoted from: Ludwig van Beethoven. The work in the mirror of its time. Collected concert reports and reviews up to 1830 , ed. and introduced by Stefan Kunze in collaboration with Theodor Schmid, Andreas Traub and Gerda Burkhard, Laaber 1987, p. 471f.

- ↑ Joseph Carl Bernard: News , in: Allgemeine Musikische Zeitung 26 (1824), No. 27 issue from July 1st, Col. 436ff .; quoted from: Ludwig van Beethoven. The work in the mirror of its time. Collected concert reports and reviews up to 1830 , ed. and introduced by Stefan Kunze in collaboration with Theodor Schmid, Andreas Traub and Gerda Burkhard, Laaber 1987, p. 472

- ↑ Joseph Carl Bernard: News , in: Allgemeine Musikische Zeitung 26 (1824), No. 27 issue from July 1st, Col. 436ff .; quoted from: Ludwig van Beethoven. The work in the mirror of its time. Collected concert reports and reviews up to 1830 , ed. and introduced by Stefan Kunze in collaboration with Theodor Schmid, Andreas Traub and Gerda Burkhard, Laaber 1987, p. 470

- ↑ Allgemeine Musikische Zeitung 29 (1827), Col. 284; quoted from: Ludwig van Beethoven. The work in the mirror of its time. Collected concert reports and reviews up to 1830 , ed. and introduced by Stefan Kunze in collaboration with Theodor Schmid, Andreas Traub and Gerda Burkhard, Laaber 1987, p. 429

- ↑ a b Ernst Woldemar: Request to the editorial staff of Caecilia , in: Caecilia 8 (1828), issue 29, p. 37

- ^ Carl Ferdinand Becker in: Caecilia 8 (1828), issue 30, pp. 135ff.

- ^ Franz Joseph Fröhlich : Beethoven's large Missa , in: Caecilia 8 (1828), p. 37; quoted from: Ludwig van Beethoven. The work in the mirror of its time. Collected concert reports and reviews up to 1830 , ed. and introduced by Stefan Kunze in collaboration with Theodor Schmid, Andreas Traub and Gerda Burkhard, Laaber 1987, p. 435