Pre-constitutional law

Pre-constitutional right (from Latin constitutio for Constitution ) is that the German constitutional discourse right that before the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany has been considered. It is still effective if it meets certain criteria. In principle, it continues to apply if it does not contradict the Basic Law , which came into force on May 24, 1949.

For the fathers and mothers of the Basic Law in the Parliamentary Council , the question was under what circumstances old imperial law, old state law , the law from the time of National Socialism and the law from the occupation should continue to exist. This was followed by the question of whether existing state law continues to apply as state law or as federal law. The Basic Law assigns certain competencies to the federal and state levels, and this assignment may have been different in previous law.

Law is pre-constitutional within the meaning of the Basic Law if it arose before the first German Bundestag met . The cut-off date was therefore September 7, 1949. Pre-constitutional law can only continue to exist if it has not been repealed before the cut-off date.

The Basic Law does not impose any time restrictions on the law itself: Even very old state law can continue to exist and continues to apply without restriction. It is also no less effective than law that arose after the deadline (“post-constitutional law”). It fits into the hierarchy of norms of the Basic Law, so that, for example, federal law takes precedence over state law . For this reason, among other things, it is important to decide whether the old law will continue to exist as state law or federal law.

It is unimportant how the law came into being: the law-making process of that time may differ from today's. The law of the Nazi dictatorship continues to apply. However, it must not contradict the idea of justice of the Basic Law; such injustice is deemed to be ineffective from the start. Many specifically National Socialist laws and other regulations have already been repealed by the occupying powers and for that reason alone no longer applicable pre-constitutional law. In 1949 the state situation in Germany was special. There are therefore no parallels to the relevant articles of the Basic Law ( Art. 123–129 GG) in other countries of the world.

Constitutional article

The Weimar Constitution (WRV) states:

- Article 178

- The constitution of the German Reich of April 16, 1871 and the law on provisional imperial power of February 10, 1919 are repealed.

- The other laws and ordinances of the Reich remain in force, provided this constitution does not conflict with them. The provisions of the peace treaty signed in Versailles on June 28, 1919 are not affected by the constitution.

- Orders of the authorities, which were made in a legally valid way on the basis of previous laws, remain valid until they are repealed by means of a different order or legislation.

Articles 123 to 129 of the Basic Law deal with pre-constitutional law. The most important provision that declares pre-constitutional law to continue to apply is in Article 123.1 of the Basic Law:

Laws from the time before the Bundestag met, continue to apply, provided they do not contradict the Basic Law.

The further provisions of Art. 124 , Art. 125 , Art. 125a , Art. 125b , Art. 125c , Art. 126 , Art. 127 , Art. 128 and Art. 129 GG are based on this.

Origin and meaning

In Art. 178 of the Weimar Constitution of 1919 it was determined: The Bismarckian constitution (1867/1871) and the law on provisional authority (1919) are repealed. Laws and ordinances remained in force if they did not contradict the new Reich constitution. A similar regulation was all the more urgent for the Basic Law in 1949 because of the National Socialist dictatorship : specifically National Socialist law should be separated from the rest.

The draft of the Herrenchiemsee was still very much based on the Weimar regulation. The Parliamentary Council (1948/49), on the other hand, wanted to allow other laws to continue to apply in addition to laws and ordinances. Law from the time between the creation of the Basic Law and the meeting of the Bundestag should also be part of it. Another subject has been added to the Parliamentary Council: the question of international treaties, because of the Reich Concordat.

According to Holtkotten, Art. 123 GG only has a declaratory effect. Since the Federal Republic is identical with the German Reich , it is not necessary to expressly confirm the earlier law. According to Stettner, Article 123 of the Basic Law makes no statement about identity. External continuity under international law does not automatically mean that the internal norms also persist. Art. 123 (1) GG is therefore not declaratory, but constitutive: the question of normative continuity could have been decided differently. A counterexample is how the law of the former GDR was dealt with : by way of the unification treaty of 1990, only a small part of it was left in force.

In contrast, according to Stettner, Article 123 (2) of the Basic Law has no constitutive character. It serves to clarify that Reich treaties such as the Reich Concordat can continue to apply within Germany, even if they are the responsibility of the states today. The Reich Concordat contains provisions under school law. The state legislators are allowed to change these provisions because they are not obliged to respect international treaties of the Reich or the Federation.

Eligible Law

Not only laws are “law” in the sense of Article 123 of the Basic Law, but every legal norm of domestic law. The author of the right is unimportant: the right can have arisen at the federal or state level, through the ordinary legislative process or, for example, as a statutory ordinance (“ emergency ordinance ”) in the Weimar Republic. Wolff: "Whether or not pre-constitutional law was properly established [...] is judged by the constitutional conditions at the time of its creation." However, the legal norm must have been effective, i.e. it must have been drawn up and promulgated. An entry into force is not absolutely necessary for the effectiveness. Customary law can also continue to apply ; So far, this has been a contentious issue above all when it restricts fundamental rights (for example, when restricting freedom of occupation , Article 12 (1) of the Basic Law). In any case, customary law must not be further developed through interpretation in such a way that a new offense arises to encroach on fundamental rights.

Old constitutional law at the level of the Reich is not meant, however. In contrast to the Weimar Constitution , the Basic Law did not expressly abolish the previous state constitution . But since the Basic Law is a new German constitution, the Weimar constitution ceased to be in force with it at the latest.

The law must have been a systematic legal norm, not a single act. There are other considerations as to whether individual files continue to apply. Law has a certain position in the hierarchy of norms. Article 123.1 of the Basic Law does not explain the rank of old law in the current hierarchy of norms, i.e. whether, for example, law in the legal rank retains it. You usually orientate yourself on the rank at the time when the legal norm was created. However, the exact rank can sometimes be unclear. Statutory ordinances, for example under the Enabling Act of 1933, had the status of laws at that time, which continues to apply.

The relevant right must have been in effect before the reference date. It must not have lost its validity, i.e. it must not have already been repealed by a legislator, for example. Even if the National Socialists or the occupying powers have repealed law, Art. 123 GG does not make it valid again. This also applies to the abolition of the federal organization of the Reich by the National Socialist unitary state.

The fathers and mothers of the Basic Law wanted to make it possible for the law to be passed before the Bundestag met. Nevertheless, this right should already be materially bound to the Basic Law. That is why law that contradicts the Basic Law lost its legal validity on May 24, 1949. That is the day on which the Basic Law came into force.

Article 123 of the Basic Law finally only refers to the old law. If, after the deadline, a German legislator “subsequently incorporated it into its will” (Wolff), then it is no longer pre-constitutional. This old-new law must meet the normal requirements of the Basic Law; this constitutional norm no longer applies. Art. 123 GG does not limit the duration of continued validity.

Timing of legislation

Right before 1867

According to Wolff, Article 123 of the Basic Law does not restrict the old law in terms of time; According to Stettner, this article of the Basic Law applies to law from "every period since the creation of the North German Confederation " (1867). The literature does not go into the time before 1867. Despite the case of the General German Exchange Order , it can be assumed that the law of the German Confederation no longer applies: there is no legal continuity between the German Confederation and the North German Confederation. In addition, the federal purpose of the German Confederation was limited to internal and external security, so that little law arose that would be considered to continue to apply.

For the period before 1867, however, one should think of state law, the law of states such as Prussia or Saxony , which formed the North German Confederation. This right can go back to the Middle Ages. This right, too, has largely been overlaid by federal and imperial law or otherwise modified or repealed.

Law from 1867 until the end of the Weimar Republic in 1933

With the establishment of the North German Confederation (constitution of July 1, 1867), a new state was undisputedly established that established federal law. According to the prevailing doctrine , this state only received a new constitution and a new name in 1871. The German Reich of 1871, as a state and as a subject under international law, is therefore identical to the North German Confederation.

Nevertheless, Article 80 of the new constitution of January 1, 1871 contains a list of those federal laws that should continue to apply. For individual member states that joined in 1870/1871, there were exceptional rules as to which federal laws should apply there (the reservation rights ). In the second new constitution, dated April 16, 1871 , there is no such provision. The provisions from the constitution of January 1st and from the November treaties (accession treaties of the southern German states) continued to apply.

After November 9, 1918, so-called revolutionary law came into being. The Council of People's Representatives governed by ordinances until the Weimar National Assembly , elected by the people, met. The validity of this right of revolution is normally recognized; it was largely a matter of transitional arrangements. On August 11, 1919, the new republican Weimar constitution came into force. She expressly declared the previous constitutional law to be ineffective. The Weimar Constitution itself was at least superimposed by the National Socialist policy in the consolidation phase - especially in 1933/1934; it was not officially canceled. It expired at the latest with the Basic Law of 1949. Exceptions like the Weimar church articles (according to Art. 140 ff. GG) are expressly mentioned in the Basic Law.

Law from the time of National Socialism

Constitutional law of the Nazi state ceased to be in force after the collapse in 1945. This also applies to other law from the time of National Socialism that contradicts the idea of justice: The Federal Constitutional Court ruled that Nazi law was invalid from the start if it contradicted fundamental principles of justice so clearly that a judge would commit injustice if he would apply it. However, the Allies have already repealed the particularly offensive parts of Nazi law through Control Council laws. As a result, Art. 123 GG no longer affects them anyway. The right from the Nazi era, on the other hand, that does not contradict the Basic Law continues to apply.

Right from the occupation until 1949

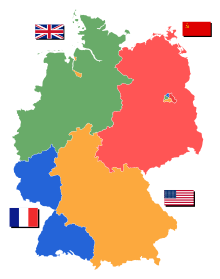

In 1945 the four main victorious powers did not dissolve Germany but took over government . For occupation law include decisions of the Allied Control Council , as well as arrangements of the individual victors for their occupation zones . The British and American zones were merged to form the Bizone and then merged with the French to form the Trizone . It essentially corresponded to the territory of the Federal Republic from 1949 to 1989/90.

During the actual occupation, i.e. from May 8, 1945 until the constitution of the Bundestag on September 7, 1949, law was also passed by German authorities. There was no federal level. First of all, the law of the German states such as Bavaria or Schleswig-Holstein from this period should be considered, which may continue to apply. The Economic Council of the Bizone or Trizone has created administrative law.

The occupation power of the occupying powers in Germany was a separate power of the Allies under international law . German legislators and the constitutional legislature were unable to dispose of this. So they could not change or revoke this occupation law. It was valid in Germany, but it was not German law. To do this, it would have had to be transformed first. Since Art. 123 GG only refers to the law of German organs , the question arises whether occupation law (law of the Allies) should also continue to apply as pre-constitutional law. The fathers and mothers of the Basic Law initially excluded the right of occupation; When the Basic Law was created, the right of occupation still took precedence over the Basic Law. Without a written stipulation, the Basic Law and thus Art. 123 only applied to a limited extent.

The case law of the Federal Constitutional Court now distinguishes between direct and indirect occupation law. Immediate occupation law as well as the law that arose through instructions from occupation organs no longer applies according to Art. 123. If an internal order of the military government led to German law, then this legal provision initially continued to apply, even if it contradicted the Basic Law . It was only repealed by the German legislature, taking into account the military government and, from 1949, the occupation statute .

The situation changed with the transition agreement when the occupation regime ended on May 5, 1955. The Federal Republic was allowed to change most of the occupation law. However, occupation law was not automatically dropped under Article 123 of the Basic Law, because then unconstitutional provisions in occupation law would not have continued to apply. It was only adjusted over time.

In 1990 the so-called Two-Plus-Four Treaty of the Federal Republic, the GDR and the Four Powers came about . The reservation rights of the main victorious powers ended. An exchange of notes between the German federal government and the three Western powers (September 27-28, 1990) provided that some provisions of the transition agreement would continue to exist. It was about individual decisions by the occupiers. In any case, after the expiry of any adjustment periods, Article 123 of the Basic Law may apply to any remaining occupation law.

During the occupation, the United Economic Territory Board of Directors enacted legislation (for the British and American zones of occupation ). Art. 127 GG deals with this . He authorized the federal government to put this law into effect in Greater Berlin and in the countries of the French zone (Baden, Rhineland-Palatinate, Württemberg-Hohenzollern) within one year (i.e. until May 23, 1950) . This was intended to promote legal standardization and has also been used in several cases. However, the Western victorious powers had reservations about applying Art. 127 to Greater Berlin. East Berlin was a four-power occupation area .

Law of the GDR and European law

The German Democratic Republic created law within the framework of its own constitutional order. In principle, this right cannot be a further applicable pre-constitutional right within the meaning of Article 123 of the Basic Law:

- The GDR was only founded one month after the cut-off date, namely on October 7, 1949.

- GDR law comes from a foreign legal source without a legal application order for the federal territory.

When German reunification in 1990, reference was made to GDR law in the unification treaty. Usually it does not continue to apply, but is superseded by German law. For part of this right there are exceptions for a transitional period. In 1990, the orientation was based on Art. 123, which can serve as an aid to interpretation. GDR law, especially that of the exception regulations, is not simply equated with post-constitutional law (i.e. normal West German law). In a way, however, it is similar to the pre-constitutional one. In any case, GDR law that continues to apply must not contradict the Basic Law or be repealed.

In 1990, little GDR law was left in force, because the Federal Republic of Germany already had a functioning legal system . By joining the Federal Republic, the GDR constitution has also become obsolete. Due to the fall of the GDR, the international treaties of the GDR no longer apply. An exception are contracts with a local reference, such as the agreement on a border line, or technical agreements.

Since the (first) Bundestag met in 1949, the law of the European institutions has been added. Art. 123 GG has no special reference to it. Pre-constitutional law, which continues to apply, is subject to the general rules as to when European law takes precedence.

Compatibility with the Basic Law

Pre-constitutional law that should continue to apply must not contradict the Basic Law. This can be the wording of the Basic Law, but also unwritten norms and further interpretations based on the Basic Law. What is decisive is what the legal community recognizes as constitutional law. The old law may deviate from the Basic Law in the form and process of its creation, because what is meant is content-related compatibility: after all, it concerns law that was not enacted by bodies in accordance with the Basic Law. If the old law only partially contradicts the Basic Law, the remaining parts continue to apply, provided "they still represent a meaningful regulation" (Stettner).

Article 123 (1) of the Basic Law, which stipulates a constitutional amendment of the Nazi legislation, does not list the contradicting old law. In the meantime, laws have been passed to streamline the law, listing the law that continues to apply (at the federal level on December 28, 1968). Art. 123 does not prohibit the legislature from doing this.

The Federal Constitutional Court usually decides whether a law contradicts the Basic Law (Art. 100, Paragraph 1). However, this only applies to post-constitutional law (law from the period after the cut-off date of September 7, 1949). In the case of pre-constitutional law, the respective competent courts examine . Art. 126 only refers to the further question of whether old law continues to apply as federal law (or as state law). Only this question is decided by the Federal Constitutional Court if necessary. In this respect, the Basic Law attaches much greater importance to the question than the draft of the Herrenchiemsee, which (Art. 140) wanted to entrust the Federal Minister of Justice with it together with state ministers. The following may submit an application to the Federal Constitutional Court: Bundestag, Bundesrat or the federal or state governments (according to § 86 I BVerfGG ). The court only examines the question of federal law / state law, not whether the old law continues to exist at all.

State treaties

In contrast to Art. 123 Para. 1, according to Stettner, Art. 123 Para. 2 has no constitutive character. It serves to clarify that Reich treaties such as the Reich Concordat can continue to apply within Germany, even if, according to the Basic Law, the content falls within the competence of the federal states. The Reich Concordat contains provisions under school law. The state legislators are allowed to change these provisions, because they are not obliged to respect international treaties of the Reich or the Federation. In the absence of a separate regulation, Article 123 (2) also applies to treaties that German states have concluded with one another or with the Reich. Art. 32 III GG makes it possible nowadays for the states to conclude state treaties in relation to those areas in which they are responsible. However, the federal government must agree to this.

Federal law and state law

The Basic Law generally assigns competences to the federal and state levels. In earlier German constitutions, this allocation may have been different from the current one. It is therefore important to clarify whether the old law is now to be viewed as federal law or state law. Federal law is higher in the hierarchy of norms: Federal law violates state law (Art. 31).

This is not just about the application of the law: it must also be clear which level the law in question may change. Articles 124 and 125 of the Basic Law are therefore intended to insert the old, still applicable law “into the competencies of the Basic Law”. If a matter is to be assigned to the federal level according to the catalog of competencies of Art. 73 old version (dated May 23, 1949) (exclusive legislation), then the old law in question becomes federal law. So one asks who the legislator would be if the law were to be governed by the constitution of the Basic Law. It is irrelevant whether the law needs the approval of the Federal Council today.

Art. 125 deals with the subject matter of competing federal legislation if there is a reference to the occupation. The old law in question becomes federal law (and not state law) if it applies uniformly to one or more zones of occupation. Or the occupation law has changed previous imperial law.

According to Schulze, the purpose of this regulation is to promote the uniformity of law. It is also important for state law from the time of occupation: there were several states in each occupation zone. If state laws coincide in terms of content and thus the law was uniform at least within an occupation zone, the law can continue to apply as federal law.

Articles 124 and 125 of the Basic Law do not cover state constitutions that continue to apply. According to Art. 70 et seq. GG, the federal government allows the states freedom for their own constitutional order (within the framework of Art. 28 I, Art. 142 GG).

There is the possibility that the old law will first become federal law via Articles 124 and 125 and that later new state law will arise that contradicts this federal law. This state law is ineffective: not only through the sentence "Federal law breaks state law", but because the state legislature did not have the competence.

Art. 125a was created through an amendment to the Basic Law of October 27, 1994. Schulze considers the provision to be constitutionally wrong and its relevance questionable. It should apply to certain cases in which federal competence has been subsequently restricted (as happened in 1994). On August 28, 2006, the article was amended as part of the federalism reform : Paragraph 3 also deals with such cases in relation to state law. Transitional issues are regulated by a new Art. 125b instead of Art. 125a. The aim of the 1994 reform was to give the federal states more powers, and in 2006 both the federal government and the federal states should become more capable of acting.

Art. 128 relates to the authority that federal organs have in relation to state organs under Art. 84, Paragraph 5. It is about the execution of federal tasks by state bodies and federal supervision. Art. 128 made it easier for the federal organs of the young Federal Republic to do their job. The powers of instruction of the old law were revived. Art. 129 regulates whether a post-constitutional government may still issue legal ordinances to which it is theoretically empowered by previous law.

Examples

The Basic Law abolishes the death penalty (Art. 102). Previous rules on the death penalty have therefore expired. If earlier imperial law made regulations for the states in the field of economic administration, it is no longer in force. It would in fact violate Article 84 of the Basic Law, which gives the Länder the right to decide on authorities and administrative procedures themselves. Still valid law from the Nazi era is, among other things, the Heilpraktikergesetz .

Situation in the German states

If the federal states have rules on pre-constitutional law at all, they are comparable to the Basic Law or the Weimar Constitution. One example is Article 186 of the Bavarian Constitution . It repeals the Bavarian constitution of 1919 and allows the laws and regulations to continue to apply if they do not contradict the new constitution.

supporting documents

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 124, Rn. 4th

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 1.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 2.

- ↑ Holtkotten, in: Wolfgang Kahl, Christian Waldhoff, Christian Walter (eds.), Bonn Commentary on the Basic Law , loose-leaf collection since 1950, CF Müller, Heidelberg, ISBN 978-3-8114-1053-4 . 52. Delivery, secondary processing, Art 81 / November 1986, Rn. 1.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 10 f.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 27.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 12-14.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 21st

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 35.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 15th

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 16.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 38.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 21 f.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 22nd

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 24 f.

- ↑ Schulze, in: Sachs, Basic Law , 3rd ed. 2002, Art. 123, Rn. 12.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 20th

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 14th

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 10.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 10, 13.

- ↑ Thomas Armbruster: Restitution of the Nazi booty. The search, recovery and restitution of cultural goods by the Western allies after the Second World War ( Writings on the Protection of Cultural Goods ), de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, p. 383 .

- ↑ Holtkotten, in: Wolfgang Kahl, Christian Waldhoff, Christian Walter (eds.), Bonn Commentary on the Basic Law , loose-leaf collection since 1950, CF Müller, Heidelberg, 52nd delivery, second processing Art 81 / November 1986, Rn. 4th

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 16 f.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 17th

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 18th

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 19th

- ↑ Schulze, in: Sachs, Basic Law , 3rd ed. 2002, Art. 127, Rn. 13 f.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 10.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 9, 11.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 11.

- ↑ Schulze, in: Sachs, Basic Law , 3rd ed. 2002, Art. 123, Rn. 27.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary , Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 7th

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 29

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 33, 34.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 20th

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 17th

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 20th

- ↑ Maunz, in: Maunz / Dürig, Commentary on the Basic Law, Art. 123, Rn. 9.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 40.

- ↑ Giegerich, in: Maunz / Dürig, Commentary on the Basic Law, 86th EL, as of January 2019, Art. 123, Rn. 47.

- ↑ Wolff, in: v. Mangoldt / Klein / Starck, GG II, Art. 123 Rn. 41.

- ↑ Schulze, in: Sachs, Basic Law , 3rd ed. 2002, Art. 126, Rn. 1-4.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 27.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 30th

- ↑ Schulze, in: Sachs, Basic Law , 3rd ed. 2002, Art. 124, Rn. 1-3.

- ↑ Schulze, in: Sachs, Basic Law , 3rd ed. 2002, Art. 125, Rn. 6 f.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 124, Rn. 7th

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 124, Rn. 9.

- ↑ Schulze, in: Sachs, Basic Law , 3rd ed. 2002, Art. 125, Rn. 1.

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 125, Rn. 1-3.

- ↑ Schulze, in: Sachs, Basic Law , 3rd ed. 2002, Art. 129, Rn. 1 f.

- ↑ Holtkotten, in: Wolfgang Kahl, Christian Waldhoff, Christian Walter (eds.), Bonn Commentary on the Basic Law , loose-leaf collection since 1950, CF Müller, Heidelberg, 52nd delivery, second processing Art 81 / November 1986, Rn. 6th

- ↑ R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (Ed.), Basic Law Commentary , Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 8f.