Periodontal disease

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| K05.2 | Acute periodontal disease |

| K05.3 | Chronic periodontal disease |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The periodontitis ( ancient Greek παρά parà , German , next ' and ὀδούς , odous , tooth', - itis , inflammation) is a bacterially induced inflammation , resulting in a largely irreversible destruction of tooth supporting structures is (periodontal ligament). Periodontitis is accompanied by a loss of support (breakdown of the teeth holding apparatus, periodontosis). A distinction is made between apical periodontitis (starting from the tip of the root) and marginal periodontitis(starting from the gum line). The two periodontitis can also merge ( paro-endo lesions ). The Periodontology (λόγος, lógos , "word, doctrine") is the study of periodontal ligaments.

Under periodontal disease (also outdated parodontosis ), however, means the loss of tooth-supporting tissues (gums, periodontal ligament and alveolar bone), which may rarely occur without inflammation.

Demarcation

This lemma treats marginal periodontitis . This is further subdivided.

In contrast, the cause of apical periodontitis is a market-dead tooth. The therapy consists of a root canal treatment , a root tip resection or the removal of the tooth ( extraction ).

Periodontium

The attachment apparatus consists of the gums ( gingiva ), the cementum , the periodontal ligament (periodontal ligament) with collagen fibers (the so-called Sharpey's fibers ) and the tooth socket .

history

Periodontology traces its origins back to John Mankey Riggs (1811–1885). Periodontitis has been referred to as Riggs disease since his treatment techniques were first introduced in 1876 . He was an opponent of the gingival resection , which was practiced at the time, and advocated the removal of tartar including debridement and tooth polishing. He also emphasized the importance of oral hygiene in preventing periodontal disease. The writer Mark Twain , who went to Riggs for treatment for his periodontal disease, put Riggs' skills on paper in his short essay Happy Memories of the Dental Chair .

In the 19th century periodontopathies had numerous names, such as alveolar pyorrhea ( blennorrhoea alveolaris), alveolitis infectiosa, caries alveolaris, Geissel medicorum, pyorrhee interalveolodentaire or pyorrhee interalveolodentaire or pyorrheea alveolaris, which was first described as a pathological phenomenon by Pierre Fauchard in 1746 . Her treatment was limited to the removal of tartar, the cupping of the gingiva and the excision of the hyperplastically altered tissue. In Germany, Oskar Weski (1879–1925) is considered a pioneer in periodontal treatment. In 1921 he coined the terms paradentium and paradentosis (which were later replaced by the etymologically correct terms periodontium and periodontitis).

Charles Cassedy Bass (1875–1975) tried drug treatment for periodontal disease. He still called the disease pyorrhea , for which he made Endameba buccalis ( Entamoeba gingivalis ) responsible. He developed the bass technique (shaking technique) for brushing teeth.

Thomas B. Hartzell refuted the Bass thesis and suggested a thorough removal of the tartar in combination with periodontal surgical measures. In 1922 Paul R. Stillman and John Oppie McCall published the first authoritative textbook in this field, A Textbook of clinical periodontia . He developed the Stillman toothbrushing technique named after him . The Stillman 's cleft, a gap-shaped receding of the gums, goes back to him.

causes

Periodontitis as gingivitis by bacterial plaque ( plaque triggered), a tough adherent biofilm . The main distinguishing feature of periodontitis is the x-ray detectable bone loss, while the recessed gum pockets in gingivitis are caused by the inflammatory swelling of the gingiva . Long-term gingivitis (inflammation of the gums) can spread to the jawbone , the periodontal membrane and the cement . However, the transition is not inevitable; especially in children and adolescents, gingivitis can persist for months and years without affecting other structures. The exact mechanisms are not yet fully understood. In both gingivitis and periodontitis, bacterial metabolism and decay products are released from the biofilm, which trigger defense reactions in the body. The main role in the tissue destruction itself plays the own immune system , which tries to eliminate the bacteria. This immune response consists of a diverse sequence of reactions and actions in which various inflammatory substances and cells are involved. Among other things, enzymes are formed that are supposed to destroy the bacteria, but also lead to the destruction of own tissue. This ultimately leads to the loss of connective tissue and bones. The result of the reaction to the bacteria is bleeding gums, pocket formation, receding gums, and eventually loosening and loss of teeth.

Of the approximately 500 different bacterial species that can occur in the oral cavity, only a few are periodontal pathogens (pathogenic in the sense of periodontal disease). These are also referred to as the main lead germs and form so-called clusters, which are specific in their socialization. They are obligatory (always) or optional (as required) anaerobic , gram-negative , black-pigmented types of bacteria.

The periodontal marker germs include in particular:

- Aa, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (old: Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans )

- Pg, Porphyromonas gingivalis

- Pi, Prevotella intermedia

- Bf, Bacteroides forsythus (new: Tannerella forsythia )

- Td, Treponema denticola

Scientific studies have shown that these facultative and obligatory anaerobes , which develop in the depths of tooth pockets, are closely associated with the development of (progressive) periodontitis.

Risk factors

Although the immune system and the presence of certain bacteria play a major role in the development of periodontal disease, there are some risk factors that affect periodontal health:

- poor or improper oral hygiene with plaque and tartar

- Tobacco use : Smokers are four to six times more likely to develop periodontal disease than non-smokers.

- genetic predisposition . Recently, various case studies as well as transversal population-representative studies have shown the previously unknown major influence of genetic predisposition on the clinical picture of periodontitis. This shows the influence of genotype variants in the area of the genes IL-1α (interleukin), IL-1β and IL-1RN (receptor antagonist). and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). This relationship is also known for the myeloperoxidase gene. Furthermore, an association between the genetic polymorphism of foreign substance metabolizing enzymes (cytochrome P450, glutathione-S-transferase, N-acetyltransferase) and the occurrence of periodontitis could be proven

- Diabetes mellitus (especially when blood sugar levels are poorly controlled). This aspect of diabetes mellitus has been known for a long time and has been proven in various studies.

- Pregnancy : Through hormonal changes, the connective tissue loosens, the gums swell and bacteria can penetrate more easily.

- open dental caries

- Mouth breathing

- Bruxism (mostly stress-related teeth grinding )

- general immune deficiency, especially " immune-suppressed " individuals (during or after chemotherapy , transplant patients , HIV- infected, etc.)

- unbalanced diet. In the past, vitamin deficiencies played a major role ( scurvy ). Overall, a diet low in processed carbohydrates but high in omega-3 fatty acids, plant-based vitamin C, vitamin D, and fiber appears to reduce periodontal inflammation.

- Inappropriately localized piercings in the oral cavity (lip, lip frenulum, tongue) or metal parts in the course of an orthodontic treatment .

Periodontitis and general diseases

The severity and course of the disease are also determined by the host reactivity, which is influenced by a large number of general diseases. On the other hand, periodontitis itself also seems to influence systemic diseases, although scientific evidence can be assumed for diabetes or chronic ischemic cardiovascular diseases; for other conditions and diseases this has yet to be finally provided. A connection between periodontitis and reactive arthritis through education has already been discussed.

Vascular disease

There are numerous studies that have been able to demonstrate a connection between periodontal diseases (e.g. periodontitis, gingivitis ) and vascular diseases (especially arteriosclerosis ). However , there is as yet no evidence as to whether this connection is causal or accidental.

diabetes

There are several studies that show that diabetics - especially those with poorly controlled blood sugar levels (HbA1c value> 7) - have a higher risk of developing periodontal disease. A lack of insulin, i.e. an increased blood sugar level, can result in deposits on the small vessels (capillaries) and impair their function: the blood flow decreases. These so-called microangiopathies affect the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the entire tissue, including the gums. Most of the time, the disease is more severe in these patients than in non-diabetics. Diabetics over 40 are particularly at risk because the severity of periodontitis increases with the duration of the diabetes. In addition, like all infections, an infection of the periodontium can lead to difficulties in controlling the blood sugar level and thus make it more difficult to adjust the blood sugar levels.

pregnancy

Since the beginning of the 1990s, dental research has known about the connection between gum disease (periodontal disease) and the increased risk of premature births or newborns with below-average birth weights. Some studies show that women with periodontal disease are almost eight times more likely to have premature birth or an underweight newborn baby than women with healthy teeth and gums.

Alzheimer's disease

Several studies show a close connection between periodontitis and Alzheimer's disease . Both diseases have an inflammatory origin. Initially, the association between the two diseases was interpreted in such a way that, with the progression of Alzheimer's disease, oral hygiene declined and the development or accelerated progression of existing periodontitis was promoted. The cause in this case would be Alzheimer's disease and the effect would be periodontitis. However, more recent study results (from around 2017) suggest that existing periodontitis can be the cause of Alzheimer's. Among other things, mechanisms are discussed that describe a direct invasion of oral pathogens, such as Treponema denticola and Treponema socranskii, from the periodontal membrane via the blood-brain barrier into the brain. The suspicion that periodontitis can lead to Alzheimer's has existed since 2008.

In 2019, a study caused a stir in which the authors were able to detect both the bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis and its metabolic products in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. Important metabolic products are toxic proteases called gingipain . In the laboratory, the authors were able to show in vitro and in vivo that gingipaines have the ability to influence the structure of tau proteins . In mice, an orally administered protease inhibitor was able to stop the multiplication of the pathogens and the progressive neurodegeneration. The COR388 inhibitor used in the study has been in a phase I clinical study with healthy volunteers since December 2017 . Another, randomized, placebo- controlled, double-blind study in phase I with Alzheimer's patients was started with this substance in February 2018.

course

In most cases it is a chronic, intermittent occurrence. This occurs mainly in adults, is rarely painful and, mostly unnoticed by those affected, only leads to tooth loosening after years. The gum line offers a relative protection for bacteria against the self-cleaning of the oral cavity by the tongue and saliva. In healthy people, the so-called seam epithelium guarantees a continuous surface between the gum and the tooth due to its adherence to the enamel. If the plaque in these niches is not carefully removed, the excretion products of the microorganisms ( exotoxins ) attack the border epithelium and some bacteria are even able to migrate through the epithelium. The body reacts to such attacks by migrating immune cells from the blood. The neutrophil granulocytes and the macrophages form a protective wall against the further penetration of foreign bodies. Gradually, the intruders are destroyed and phagocytosed (“eaten”). Various endotoxins are released in the process. Both the exotoxins and the endotoxins and some decay products of the body's immune cells represent a stimulus. In order to protect the surrounding tissue from these stimuli and to prevent the inflammation from penetrating into the depths, the body activates u. a. Osteoclasts . Their task is a targeted breakdown and remodeling of the bone tissue.

If the body has good defenses, the microorganisms can be prevented from penetrating into the depths for a long time. The balance of power in this struggle, however, is very unstable. A deterioration in the body's defenses, a strong multiplication of bacteria or a change in the aggressiveness of the microorganisms then lead to the inflammation progressing in depth. In the course of this, there is constant bone loss that can only be stopped by completely removing the stimuli. The bone loss appears predominantly horizontally on X-ray images, as the osteoclasts form the fissured bone tissue during the rest phases of the inflammation and thus adapt to the new conditions. Because of the slow and long course of the disease, this form of inflammation is called chronic periodontal disease .

A distinction is made from aggressive periodontitis , which quickly leads to extensive bone loss and sometimes already occurs in childhood. That is why it was called juvenile periodontitis in the earlier nomenclature. In X-ray images, the bone loss appears as a sharp-edged vertical crater along the root surface in this rapidly progressing course, since no remodeling has taken place. Particularly aggressive pathogens and / or a non-functioning local defense against bacterial stimuli are discussed as causes for this rarer form.

As the inflammation progresses deep into the periodontal pockets, diagnosis without dental aids is often difficult for those affected. The following signs can indicate a disease of the periodontium and should be clarified by the dentist:

- Signs of gingivitis

- Bleeding gums

- Redness, swelling and tenderness of the gums

- in active inflammatory stages as well

- Bad breath ( halitosis )

- Pus formation on the gums

- with advanced course

- Receding gums ("the teeth seem to be getting longer")

- Tooth loosening / migration.

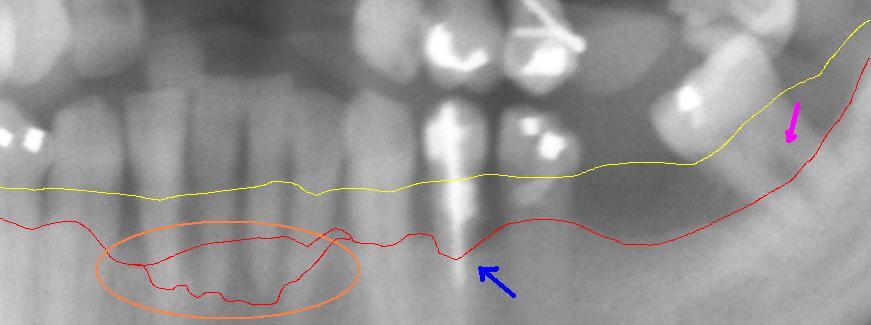

Panoramic x-ray

Detail from a panoramic x-ray of advanced periodontitis in the left lower jaw with bone loss between 30% and 80%. The red line shows the current bone progression. The yellow line shows the original course of the gingival margin, which runs about 1 to 2 mm above the physiological bone boundary. The pink arrow on the right shows an exposed bifurcation . The blue arrow in the middle points to particularly severe bone loss . The circled area shows a particularly aggressive course of periodontitis in the area of the lower front teeth.

prophylaxis

In order to prevent periodontitis, in addition to actually brushing your teeth with a toothbrush, care should be taken to clean the interdental spaces with dental floss or interdental brushes and to remove plaque from the back of the tongue. With regular check-ups at the dentist in connection with professional teeth cleaning every three to six months, cleaning niches can be cleaned and assistance with home oral hygiene can be given. If the risk is increased, for example due to pregnancy or severe stress, the prophylaxis intervals at the dentist can be shortened in order to be able to react to changes in the periodontium as early as possible. The risk factors mentioned (such as nicotine abuse , diabetes cessation) must be reduced.

Recent research also recommends BLIS (bacteriocin-like inhibiting substances) as a possible prophylaxis.

The consequences of tooth loss, especially the sometimes very costly prosthetic measures , which often follow a periodontal treatment, as well as the knowledge of the general medical context, mean that the diagnosis, treatment and, above all, the prevention of this disease are becoming ever greater Importance. Periodontitis is like a widespread disease - almost everyone is more or less affected by it at some point in their life. In the age group over forty, more teeth are lost to periodontal disease than to caries.

Diagnosis

A comprehensive diagnosis determines the type, severity and course of the disease. Clinically, one assesses the overall condition of the teeth, the loosening of the teeth, the depth of the pockets, which is determined using periodontal probes , the receding gums and the patient's oral hygiene. In addition, the course of the bone is determined by x-rays. In some cases, additional microbiological (detection of certain periodontal pathogenic bacteria) and genetic (detection of a genetic predisposition) tests are carried out. A referral to a general practitioner to rule out a systemic disease (diabetes, HIV, leukemia, etc.) may also be necessary.

Necrotizing periodontal disease

Among the necrotizing periodontal disease are necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP) are summarized. Both forms show a clinically similar appearance with interdental gingival necrosis and bleeding, severe pain, pronounced fetor ex ore ( bad breath ) and pseudomembranes . With NUP, there is also a loss of periodontal support tissue. In severe cases, lymphadenopathy , a general feeling of illness and fever can also occur.

therapy

The therapy consists in the inflammatory condition to remove the gums and tooth-supporting tissues and to remove plaque and tartar, and inflammatory factors and the pathogenic bacterial flora. The treatment is divided into different phases with different measures.

In the so-called hygiene phase, all hard and soft plaque located supragingivally (above the gum line) are removed ( professional tooth cleaning , PZR). The patient is also shown how he can perform optimal dental care at home. This process usually has to be repeated. In addition, in this phase fillings or root fillings must be placed or renewed and teeth that are not worth preserving must be extracted. This eliminates further bacterial foci in the oral cavity. Bacterial growth can be controlled and reduced by using various flushing liquids or medication. These hygiene measures alone can bring about a noticeable improvement in many of those affected.

Then, if necessary, the so-called closed treatment phase begins, in which the hard and soft deposits lying subgingivally (below the gumline) are removed (closed debridement ). This is done with curettes (specially shaped hand instruments), with sound and ultrasound-operated devices or with the use of certain lasers . After two to three weeks of healing, the result of this treatment is checked by measuring the probing depth again and, if necessary, the measures are repeated at individual points.

In the case of very deep gingival pockets (over six millimeters), which have not been sufficiently reduced by the hygiene measures and the closed treatment, it may be necessary to switch to the open treatment phase. The areas are surgically opened so that the measures of the closed treatment can be repeated under sight. In this case it is sometimes also possible to fill opened and cleaned bone pockets with bone substitute materials ( Guided Bone Regeneration , GBR) or to cover them with membranes ( Guided Tissue Regeneration , GTR). However, the latter two measures are not contractual benefits from the statutory health insurance .

Under certain conditions (aggressive, rapidly progressing forms of periodontitis) it makes sense to supplement the treatment with the use of antibiotics and / or the " full mouth disinfection " therapy. Metronidazole is used in supportive antibiotic therapy for periodontitis with anaerobic attack , such as Porphyromonas gingivalis . In a Swiss field study, five periodontal types (associations of bacteria) were microbiologically proven, which are to be treated differently: With three types, a curettage was sufficient, with two types, certain antibiotics had to be administered in addition. These can be given in tablet form (systemic) or they are placed directly in the gingival pocket (locally). In both cases, it is advantageous to carry out a germ determination beforehand in order to treat as precisely as possible. However, there is no point in treating the infection with antibiotics without first cleaning your teeth. The bacteria are almost completely protected in their biofilm from the effects of the antibiotic drug. The bacteria only become accessible to the antibiotics when the biofilm is destroyed.

Another local drug treatment method (additional direct introduction into the gingival pocket) is that with an antiseptic chlorhexidine chip . This ensures a lasting sterility in the inflamed gum pocket and biodegrades by itself. Since it is often a chronic form of periodontal disease, the chlorhexidine chip also has the advantage that the germs do not develop antibiotic resistance , since chlorhexidine is not an antibiotic.

Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy is used as an adjuvant . After the instrumental cleaning, the inflammation-causing microorganisms are colored with the help of a dye solution and then exposed to a low-energy laser ( diode laser ). The subsequent reaction leads to the formation of aggressive oxygen, which is supposed to destroy the bacteria, also in the biofilm.

Researchers at the Universities of Würzburg and Hohenheim have recently shown that nutrition plays a major role. In a clinical study in which patients consumed copious amounts of lettuce juice, which contains large amounts of vegetable nitrate, the extent of gingivitis decreased.

Assessment by the IQWiG

The advantages and disadvantages of various treatments for inflammatory diseases of the periodontium are the subject of a study by the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). In a preliminary report dated January 24, 2017, this means that there are a lot of studies on periodontal disease. However, these are very often not usable. Meaningful study data that showed relevant differences in treatment outcomes would only be available for two therapies:

- to closed mechanical therapy (GMT) versus no therapy and

- a customized oral hygiene training program compared to a standard instruction.

A hint of a (greater) benefit of the GMT or the GMT combined with an individually adapted oral hygiene training program could be derived from the available data. The preliminary report met with massive criticism from the relevant specialist societies. “With its rigid methodology, IQWiG excludes numerous internationally recognized study results from the assessment”.

forecast

If treated correctly and in good time, periodontitis can almost always be stopped, but this treatment is sometimes very tedious and always heavily dependent on the cooperation of the patient. Since periodontitis is an expression of a successful bacterial attack against the once intact tooth-gum border, everyone affected must be aware that even after this inflammation has been successfully eliminated, there is still a risk of relapse. This is why regular follow-up care is necessary even after the end of the actual therapy in order to counteract a renewed flare-up of the inflammation as early as possible.

If left untreated, periodontitis almost always leads to tooth loss and, as a result, to aesthetic and functional impairments. Periodontitis is also a risk factor for general medical conditions. A connection between periodontal diseases and an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases ( heart attack ), diabetes mellitus and diseases of the rheumatic type is scientifically proven. More recent studies have also shown that untreated periodontitis increases the risk of premature birth by a factor of seven and that low birth weight can also be causally related to periodontitis.

Maintenance therapy

After periodontitis treatment, lifelong maintenance therapy is necessary, which consists of regular oral hygiene by the patient and also regular professional tooth cleaning by the dentist or a correspondingly trained dental assistant . The latter are carried out quarterly to half-yearly, depending on the severity of the disease.

Billing of services from the statutory health insurance

In Germany, the statutory health insurances reorganized periodontal treatment with effect from January 1, 2004. This is intended to promote the early detection of slowly progressing periodontal diseases and at the same time encourage the patient to do more work on his own. The idea behind this is that the patient should ensure good oral hygiene himself as the best prophylaxis. BEMA number 04 has been added to the service catalog: once every two years, the creation of a periodontal screening index (PSI) can be billed to the health insurance company. Since then, the removal of tartar (BEMA number 107) can only be billed once a year within the framework of the GKV. Instead, patients should arrange prophylaxis services privately with the contract dentist if necessary and pay the costs themselves. The amount of the related costs varies according to the patient, illness and practice (number of teeth to be cleaned, degree of soiling, tooth position, etc.). In some cases, statutory health insurances grant a subsidy for professional tooth cleaning (PZR), in some cases the costs are covered by supplementary dental insurance.

In order to receive the cost commitment for periodontal therapy from a health insurance company, this must first be applied for and approved in writing at the health insurance company by means of a periodontal status. The basis for a performance commitment are the BEMA guidelines, which were approved by the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA). There it says:

Participation of the patient

“The dentist has to inform the patient about the necessity of active participation in all phases of therapy. Participation consists in the patient actively trying to reduce exogenous and endogenous risk factors according to his individual possibilities, to attend the necessary treatment appointments and to use any therapeutic agents that may be used as indicated. Before and during periodontal treatment, it must be checked to what extent periodontal treatment is indicated according to these guidelines and to what extent it is economically viable. This particularly depends on the cooperation of the patient.

Patients who still do not cooperate sufficiently or who practice inadequate oral hygiene, the dentist must again point out the need to cooperate and explain that the treatment must be restricted or, if necessary, terminated. If the dentist determines that the patient is not cooperating sufficiently, the dentist must redefine the treatment goal and, if necessary, end the treatment,

- if a change in the patient's behavior appears to be impossible in the foreseeable future or

- if he discovers in a further treatment appointment that there has been no significant change in behavior.

The dentist has to inform the health insurance company about this. The treatment can only be continued if the requirements according to No. 1 paragraph 2 are met. "

Pretreatment

A further prerequisite for the assumption of costs by the GKV is the implementation of all necessary pre-treatment measures in order to put the teeth in a condition that the patient can keep clean himself. Furthermore, all surgical and conservative services must have been carried out in advance, for example the extraction of teeth that cannot be preserved, fillings and root canal treatments. These include, for example

- the examination of the preservability of the respective tooth

- a gingival pocket depth of at least 3.5 mm

- checking the degree of loosening of the respective tooth

- the evaluation of the x-rays

- testing the vitality of the teeth

- open approach

- closed approach

The cost of any additional services such as

- Laser treatments

- Determination of the types of bacteria

- Determination of genetic risk

can be arranged privately with statutory insured patients. The supporting periodontal therapy (control and follow-up treatments after the main treatment borne by the health insurance company), the so-called maintenance therapy, is largely a private service.

If services are provided that go beyond the economic efficiency requirement in accordance with Section 12 of the Social Code Book V (especially higher-quality fillings or non-contractual services), they must be agreed privately with the patient.

The implementation of a periodontal treatment - like the implementation of any other contract dental service - must not be made dependent on a private additional payment or private service.

Appraisal

The health insurance companies can make the cost assumption declaration dependent on an appraisal by an expert appointed by mutual agreement by the health insurance companies and dental associations . The appraiser checks compliance with the BEMA guidelines. If the reviewer does not approve of the treatment, a senior reviewer procedure can be initiated. The senior experts are appointed at the federal level.

PA treatment

Following the pretreatment, if necessary assessment and approval, the actual periodontal treatment can begin, which the health insurance company takes over within the scope of the BEMA guidelines.

Measures to ensure the success of the treatment

The BEMA guidelines also stipulate that regular examinations of the patient after the completion of a systematic treatment for periodontal disease (diseases of the tooth supporting apparatus) is necessary because of the risk of bacterial recolonization of the pockets. Local measures on individual periodontals may have to be repeated.

The first follow-up examination should take place after six months if the procedure is closed and after 3 months at the latest if the procedure is open.

Billing of private services

In addition to the private services already mentioned, a whole range of periodontal therapy procedures or accompanying therapies are not included in the service catalog of the statutory health insurance, for example:

- augmentative procedures (bone augmentation procedures),

- free ginigiva transplants (grafting of gums),

- Bone grafts,

- functional therapeutic services,

- Widening of the fixed gingiva,

- professional tooth cleaning,

- The periodontal screening index was collected more than once in two years ,

- repeated diagnosis using periodontal status,

which can be provided for private patients or by means of a private written additional agreement before the start of treatment for statutory health insurance patients .

The situation in Germany

Almost 12 million Germans suffer from periodontitis. In 2007, more than half of the 35 to 44 year olds in Germany suffered from periodontitis, around 20 percent even from a severe form. This was the result of the Fourth German Oral Health Study (DMS IV), prepared by the Institute of German Dentists on behalf of the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Dentists ( KZBV ) and the German Dental Association . One reason for the increase in periodontal diseases is the improved oral health: Due to the good caries prophylaxis and dental care, older people keep their own teeth longer and longer. With increasing age, however, the teeth are exposed to a high risk of periodontitis. For example, more than 40 percent of 65 to 74 year olds suffer from a severe form of periodontal disease.

Epidemiology

In a WHO study on the epidemiology of periodontal disease, it was found that periodontal disease in its severe form occurs in around 10 to 15 percent of the population. The worldwide loss of productivity due to periodontal disease is estimated at approximately $ 54 billion annually.

Animals

Animals, such as dogs and cats , can also be affected by periodontal disease. The course is similar to that in humans. Here, too, regular check-ups and tartar removal are the most common treatment methods.

literature

- American Academy of Periodontology; Annette Bergfeld (translation, editing): Periodontal diseases and health . Phillip Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-934341-02-0 .

- German Society of Periodontology e. V. (Ed.): Risk compendium periodontitis . Quintessenz-Verlag, Berlin a. a. 2002, ISBN 3-87652-433-4 .

- C. Villages: Periodontal disease and general health. In: zm. - Dental communications, ISSN 0341-8995 , zm 92, number 9, 2002, pp. 38-43.

- S. Zimmer, A. Jordan, University of Witten Herdecke: Adjuvant periodontitis therapy with chlorhexidine-xanthan gel. (PDF; 166 kB) Book excerpt: The introduction of prophylaxis in the dental practice

- Patient information from the German Dental Association and the German Society for Dentistry, Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine on periodontal treatment (PDF; 110 kB), regenerative therapy (GTR) (PDF; 115 kB), microbiological diagnostics and periodontal therapy (PDF; 77 kB) and professional tooth cleaning (PZR) (PDF; 109 kB).

Web links

- Periodontitis and Heart Attack University of Kiel

- German Society for Periodontology

- Austrian Society for Periodontology

- Swiss Society for Periodontology

- European Federation of Periodontology

- Department of Periodontology Julius Maximilians University of Würzburg

Individual evidence

- ↑ periodontitis DGParo. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ Pschyrembel. Clinical Dictionary. 255th edition. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1986, ISBN 3-11-007916-X , p. 1262.

- ^ WJ Maloney: A Periodontal Case Report by Dr. SL Clemens. In: Journal of Dental Research. 89, 2010, p. 676, doi: 10.1177 / 0022034510366677 .

- ↑ Mark Twain, Frederick Anderson, Lin Salamo, Bernard L. Stein: Mark Twain's Notebooks & Journals . Volume II: 1877-1883 . University of California Press, 1975, ISBN 978-0-520-90553-5 , pp. 53 ( books.google.com ).

- ↑ Ullrich Rainer Otte: Jakob Calmann Linderer (1771-1840). A pioneer in scientific dentistry. Medical dissertation, Würzburg 2002, p. 20.

- ↑ Günter Koch: Oskar Weski: his life and work above all as a pioneer of paradontology. Dissertation. LMU Munich, 1969.

- ^ Oskar Weski: Review of Current Dental Literature: New Denomination of the So-Called Alveolar Pyorrhea. In: The Dental cosmos. Volume 74, Issue 2, February 1932, pp. 200-201. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ CC BASS: Habitat of Endameba buccalis in lesions of periodontoclasia. In: Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Volume 66, Number 1, October 1947, ISSN 0037-9727 , pp. 9-12. PMID 20270656 .

- ^ Paul R. Stillman, John Oppie McCall: A Textbook of Clinical Periodontia. A Study of the Causes and Pathology of Periodontal Disease and a Consideration of Its Treatment. Macmillan Company, 1922.

- ↑ Malvin E. Ring: History of Dentistry. Könemann Verlag, 1997, ISBN 3-89508-599-5 , p. 303.

- ↑ Sylke Dombrowa: The usefulness of microbiological diagnostics in the treatment of periodontitis and peri-implantitis - Part 1. (No longer available online.) November 23, 2010, archived from the original on December 15, 2013 ; Retrieved November 22, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Falk Schwendicke, Christof E. Dörfer, Toni Meier: Global smoking-attributable burden of periodontal disease in 186 countries in the year 2015 . In: Journal of Clinical Periodontology . tape 45 , no. 1 , November 21, 2017, ISSN 0303-6979 , p. 2-14 , doi : 10.1111 / jcpe.12823 ( wiley.com [accessed May 14, 2018]).

- ^ NJ López, L. Jara, CY Valenzuela: Association of interleukin-1 polymorphisms with periodontal disease. In: Journal of Periodontology . Volume 76, Number 2, February 2005, pp. 234-243, ISSN 0022-3492 . doi: 10.1902 / jop.2005.76.2.234 . PMID 15974847 .

- ↑ P. Meisel, A. Siegemund, S. Dombrowa, H. Sawaf, J. Fanghaenel, T. Kocher: Smoking and polymorphisms of the interleukin-1 gene cluster (IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, and IL-1RN) in patients with periodontal disease. In: Journal of periodontology. Volume 73, Number 1, January 2002, pp. 27-32, ISSN 0022-3492 . doi: 10.1902 / jop.2002.73.1.27 . PMID 11846196 .

- ↑ L. Quappe, L. Jara, NJ Lopez: Association of interleukin-1 polymorphisms with aggressive periodontitis. In: J Periodontol. 75 (11), 2004, pp. 1509-1515. PMID 15633328

- ↑ MJ McDevitt, HY Wang, C. Knobelman, MG Newman, FS di Giovine, J. Timms, GW Duff, KS Kornman: Interleukin-1 genetic association with periodontitis in clinical practice. In: J Periodontol. 71 (2), 2000, pp. 156-163. PMID 10711605

- ↑ Y. Soga, F. Nishimura, H. Ohyama, H. Maeda, S. Takashiba, Y. Murayama: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene (TNF-alpha) -1031 / -863, -857 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs ) are associated with severe adult periodontitis in Japanese. In: J Periodontol. 30 (6), 2003, pp. 524-531. PMID 12795791

- ↑ P. Meisel, R. Timm, H. Sawaf, J. Fanghänel, W. Siegmund, T. Kocher: Polymorphism of N-acetyltransferase (NAT2), smoking and the potential risk of periodontal disease. In: Arch Toxicol. 74 (6), 2000, pp. 343-348. PMID 11846845

- ↑ JS Kim, JY Park, WY Chung, MA Choi, KS Cho, KK Park: Polymorphisms in genes coding for enzymes metabolizing smoking-derived substances and the risk of periodontitis. In: J Clin Periodontol. 31 (11), 2004, pp. 959-964. PMID 15491310

- ↑ Gabriel Mohr: Investigation of the genetic polymorphism of N-acetyltransferase-2 (NAT2) in patients with aggressive periodontitis. 2006, DNB 982950683 .

- ↑ RC Oliver, T. Tervonen: Diabetes - a risk factor for periodontitis in adults? In: Journal of periodontology. Volume 65, Number 5 Suppl, May 1994, pp. 530-538, ISSN 0022-3492 . doi: 10.1902 / jop.1994.65.5s.530 . PMID 8046569 . (Review).

- ↑ Schäfer, Edgar, Klimek, Joachim, 1947-, Attin, Thomas, 1963-: Introduction to tooth preservation : examination knowledge of cariology, endodontology and periodontology . 7th revised edition. Cologne 2018, ISBN 978-3-7691-3652-4 .

- ↑ Barbara Noack: Interaction: Periodontitis and general diseases. June 4, 2008, accessed December 10, 2013 .

- ↑ Katarzyna J. Maresz, Annelie Hellvard, Aneta Sroka, Karina Adamowicz, Ewa Bielecka, Joanna Koziel, Katarzyna Gawron, Danuta Mizgalska, Katarzyna A. Marcinska, Malgorzata Benedyk, Krzysztof Pyrc, Anne-Marie Quirke, Roland Jonsson, Patrick Saba J. Venables, Ky-Anh Nguyen, Piotr Mydel, Jan Potempa, Barbara I. Kazmierczak: Porphyromonas gingivalis Facilitates the Development and Progression of Destructive Arthritis through Its Unique Bacterial Peptidylarginine Deiminase (PAD). In: PLoS Pathogens . 9, 2013, p. E1003627, doi: 10.1371 / journal.ppat.1003627 .

- ↑ RT Demmer, M. Desvarieux: Periodontal infections and cardiovascular disease: the heart of the matter. In: Journal of the American Dental Association . Volume 137 Suppl, October 2006, pp. 14S-20S, ISSN 0002-8177 . PMID 17012731 .

- ↑ B. Willershausen et al .: Association between chronic dental infection and acute myocardial infarction. In: J Endod . 35 (5), May 2009, pp. 626-630.

- Jump up ↑ Yvonne Jockel-Schneider, Inga Harks, Imme Haubitz, Stefan Fickl, Martin Eigenhaler, Ulrich Schlagenhauf, Johannes Baulmann, Giuseppe Schillaci: Arterial Stiffness and Pulse Wave Reflection Are Increased in Patients Suffering from Severe Periodontitis. In: PLoS ONE. 9, 2014, p. E103449, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0103449 .

- ↑ a b F. B. Teixeira, MT Saito et al. a .: Periodontitis and Alzheimer's Disease: A Possible Comorbidity between Oral Chronic Inflammatory Condition and Neuroinflammation. In: Frontiers in aging neuroscience. Volume 9, 2017, p. 327, doi : 10.3389 / fnagi.2017.00327 , PMID 29085294 , PMC 5649154 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ Y. Leira, C. Domínguez et al. a .: Is Periodontal Disease Associated with Alzheimer's Disease? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. In: Neuroepidemiology. Volume 48, number 1–2, 2017, pp. 21–31, doi : 10.1159 / 000458411 , PMID 28219071 (review).

- ↑ P. Ganesh, R. Karthikeyan et al. a .: A Potential Role of Periodontal Inflammation in Alzheimer's Disease: A Review. In: Oral health & preventive dentistry. Volume 15, number 1, 2017, pp. 7-12, doi : 10.3290 / j.ohpd.a37708 , PMID 28232969 (review).

- ↑ AR Kamer, RG Craig et al. a .: Inflammation and Alzheimer's disease: possible role of periodontal diseases. In: Alzheimer's & Dementia. Volume 4, Number 4, July 2008, pp. 242-250, doi : 10.1016 / j.jalz.2007.08.004 , PMID 18631974 (Review).

- ↑ Stephen S. Dominy, Casey Lynch et al. a .: Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer's disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. In: Science Advances. 5, 2019, p. Eaau3333, DOI: 10.1126 / sciadv.aau3333 .

- ↑ Joachim Czichos: Bacterial infection as a cause of Alzheimer's dementia. In: Wissenschaft-aktuell.de. January 24, 2019, accessed January 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Clinical study (phase I): Study of COR388 HCl in Healthy Subjects at Clinicaltrials.gov of the NIH

- ↑ Clinical Study (Phase I): A Multiple Ascending Dose Study of COR388 at Clinicaltrials.gov of the NIH

- ↑ A. Meinelt: Molecular methods for the detection of the oral-probiotic strain Streptococcus salivarius ssp. salivarius K12 and application in vitro and in vivo. Dissertation. RWTH Aachen University, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ↑ T. Eberhard: The antimicrobial photodynamic therapy as adjuvant minimally invasive periodontitis and peri-implantitis therapy: A longitudinal cohort study from practice; 5 year results. In: ZWR-Das Deutsche Zahnärzteblatt. Volume 121, No. 9, 2012, pp. 428-439.

- ↑ Ulrich Schlagenhauf: For healthy teeth. (PDF) In: UNI.KLINIK, health magazine of the Würzburg University Hospital. Retrieved November 4, 2016 .

- ↑ Systematic treatment of periodontal disease: preliminary report published , IQWiG, press release, January 24, 2017.

- ^ Statement by the German Society for Periodontology on the use of the IQWiG for the systematic treatment of periodontal disease , German Society for Periodontology , press release, January 25, 2017.

- ↑ Disservice to the patients, KZBV criticizes IQWiG preliminary report "Systematic treatment of periodontal disease" , National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Dentists , press release, January 24, 2017.

- ↑ G-BA, BEMA guidelines (PDF; 89 kB).

- ↑ BEMA-Z, PAR guidelines (PDF; 239 kB)

- ^ Oral health of the German population. As of 2007 .

- ^ Epidemiology of periodontal disease. In: H. Wolf u. a .: Color atlases of dentistry. Volume 1: Periodontics. 3. Edition. Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-13-655603-8 , p. 75.

- ^ S. Listl, J. Galloway, PA Mossey, W. Marcenes: Global Economic Impact of Dental Diseases . In: Journal of Dental Research . August 28, 2015, doi : 10.1177 / 0022034515602879 .