Great crested grebe

| Great crested grebe | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Breeding pair of Great Crested Grebes ( Podiceps cristatus ) at the Müritz |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Podiceps cristatus | ||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The great crested grebe ( Podiceps cristatus ) is a bird art from the family of grebes (Podicipedidae). The mallard-sized bird is the largest, most common and best-known member of this family of waterfowl . It breeds on freshwater lakes and larger ponds with banks overgrown with reed. His courtship behavior, which takes place on open water and can be easily observed, is particularly noticeable. The courtship elements include violent head shaking with a spread hood and the so-called penguin pose, in which the birds lift themselves out of the water almost vertically by paddling their feet quickly.

The great crested grebe was bird of the year 2001 in Germany and Austria .

description

Great crested grebes are 46 to 51 cm long and have a wingspan of 59 to 73 cm. They weigh between 800 and 1400 g. The gender dimorphism is only slightly pronounced. The males are slightly larger than the females and have a slightly wider collar and a longer hood in their splendid dress.

The beak is red in all clothes with a brown ridge and a light tip. The iris is red with a light orange ring around the pupil. The legs and the flaps are greenish gray.

Splendid dress

In the splendid dress, the forehead, crown and neck are black. The head side and neck feathers are elongated and can be straightened up when excited. A light stripe runs between the black top of the head and the eye. The cheeks are white. The elongated chestnut-brown ear and lower cheek feathers, which are spread when excited, form a black-edged collar. The back neck is gray-black, while the sides of the neck and the front neck are white. The top of the body is brownish black with reddish sides. The underside of the body and the chest are white. The wings are brown-gray with the underside being lighter and with a white base. The arm wings, on the other hand, are either completely white or have dark spots on the outer flags.

The full moult from the magnificent dress to the plain dress begins as early as the breeding season in June and can drag on into December in some individuals. However, it is usually completed by the end of September or October. Great crested grebes lose all hand wings at the same time during this moult and are then unable to fly for about four weeks. Males usually start moulting a little earlier than females.

The moulting from the plain to the splendid coat begins in the wintering areas and is completed in the adult birds at the end of March to the beginning of April. In young birds that have not yet completed their first year of life, it continues until May. The spring moult is a partial moult, in which the plumage of the head, neck and upper part of the front body is changed.

Plain dress

In the plain dress , the top of the head is black-gray for both sexes. The hood is short, the collar is either completely absent or only indicated by individual black and red feathers. The cheeks and throat are white. The neck is also predominantly white and only has a narrow gray band on the back of the neck. The top of the body is dark with broader light feather edges. The sides of the body are gray. The undersides of the body and the chest are white.

Down chicks and young birds

Newly hatched down chicks of the great crested grebe have a short and thick down dress . The head and neck are black and white striped lengthways. The median is white. There are brown spots of various sizes on the white throat. The back and the sides of the body are initially less contrasting brownish white and blackish brown streaked, in older down boys it is uniformly dark gray. The underside of the body and the chest are white.

The down chicks have bare red spots on their heads between the eyes and beak, as well as a triangular red vertex. The iris is blackish, the beak is whitish-pink with a white tip and two almost vertical black bands around both halves of the beak. One of these is at the base of the beak and the second behind the tip. The legs are dark gray, the toes greenish gray with swimming lobes lined with narrow brownish pink.

The youth plumage resembles the winter plumage of the adult birds. However, they have a white spot on the blackish forehead and light stripes on the sides of the head behind the eye and at the level of the brow. The collar is indicated by individual black and red feathers. The wings are slate brown with a white base, the wings are white with brown spots on the inside. Even in their first winter plumage, many young birds have down on their heads and on the top of their bodies. In her first splendid dress, the collar is a little less developed. The front wing section does not yet have the pure white coloring that is characteristic of adult birds.

Locomotion and voice

Great crested grebes are diurnal birds. They only look for food during the bright time of the day. During the courtship season, however, their voices can also be heard at night. They rest and sleep on the water. Only during the breeding season do they occasionally use temporary nest platforms to rest or the nests that are released after the young have hatched. After a short take-off run, you will rise from the water. The flight is fast with rapid wing flapping. You stretch your feet back and your neck forwards during the flight. The white arm wings are clearly visible in flight.

They often swim in the middle of lakes and repeatedly disappear during dives of up to a minute and depths of 5 to 20 meters.

Great crested grebes call out frequently and loudly, a rasping noise that sounds like cheeky-cheeky-cheeky .

distribution

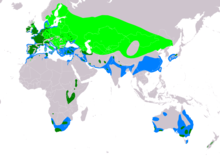

The great crested grebe is a widespread bird in the mid-latitudes and subtropics from southwest Europe and north Africa to China. The species is also found south of the Sahara as well as in the south and east of Australia and the South Island of New Zealand. Depending on the geographic location, they are migratory or resident birds. Great crested grebes that leave their breeding area during the winter months either spend the winter on large inland lakes or in coastal waters. Lake Geneva, Lake Constance and Lake Neuchâtel are among the European lakes, where numerous great crested grebes gather in the winter months. They also winter on the western European Atlantic coast, where they appear in large numbers in October and November and stay until late February or early March. Other important winter spots are the Caspian Sea, the Black Sea and individual inland waters in Central Asia. In East Asia, the wintering areas are in southeastern and southern China, Taiwan, Japan and India. Here they are also mainly in the coastal area.

In Central Europe the great crested grebe is quite common in areas rich in water up to the low mountain ranges. The highest breeding sites in Switzerland are found at 1,050 meters above sea level. In Germany, the altitude ranges up to 810 meters. The eastern populations of Central Europe are migratory birds that winter on the coasts of Western and Southern Europe. In Germany great crested grebes are mostly resident birds, which also migrate to the coasts when lakes have frozen for longer.

There are three subspecies of the great crested grebe:

- P. c. cristatus in the Palearctic

- P. c. infuscatus in sub- Saharan Africa

- P. c. australis in Australia and New Zealand

habitat

The great crested grebe breeds in larger, still waters with a belt of reeds in the lowlands. It needs fish-rich waters that are at least five hectares in size. It can only rarely be seen on a hectare of water. The great crested grebe is also usually absent from oligotrophic and mesotrophic waters. In addition to open water, the body of water must have a reed belt and bushes protruding into the water to enable nest building.

During the autumn period when the great crested grebes roam, they can also be found in bodies of water without aquatic plants, provided they are rich in fish. During the migration they use open inland lakes, rivers and coastal waters. On the other hand, they avoid salty inland waters.

food

Great crested grebes mainly eat small fish, which they hunt while diving. Mostly these are surface types that reach an average length of 10 to 15 centimeters. The maximum size of fish that great crested grebes eat is 25 centimeters. Their typical prey fish on freshwater include Moderlieschen, carp, roach, white fish, gobies, perch, pike and pikeperch. But also tadpoles , frogs , crustaceans, spiders and aquatic insects as well as seeds are part of their diet. More detailed studies have shown that there are significant differences in food composition between individual populations. There are individual populations in which fish food does not play a major role in summer and the main food consisted of beetles and bedbugs. The daily requirement is about 200 grams. Young are first fed insects. In addition, like many grebes, eating feathers can be observed. Even the young birds are occasionally fed with feathers. In their wintering areas they only feed on fish. In salt water, gobies, herring fish, sticklebacks, cod and carp fish make up the majority of their prey.

Great crested grebes eat larger fish on the surface of the water. The prey animals are usually swallowed head first. They eat small fish while they are still under water. Great Crested Grebes typically dive for less than 45 seconds while foraging. They usually swim between two and four meters underwater. The maximum proven diving distance is 40 meters. Insects are also snatched from the air or pecked from the surface of the water. Occasionally they scare away fish and insects that are among the aquatic plants with quick leg movements.

Reproduction

Great Crested Grebes reach sexual maturity towards the end of the 1st year of life at the earliest, but usually do not breed successfully in the 2nd year of life. They have a monogamous seasonal marriage.

In Central Europe, great crested grebes usually arrive at their breeding site in March / April. The breeding season begins at the end of April to the end of June, or even in March if the weather conditions are favorable. They raise one or two broods a year.

Great crested grebes maintain a nesting and feeding area during the breeding season. Colony-like breeding is possible when there is a rich supply of food and few places that are suitable for nest building. Such colonies are known from Western Europe, the Barabasteppe , the Azov region and Estonia , among others . The colonies usually consist of ten to twenty breeding pairs, but in exceptional cases up to 100 pairs breed in close proximity to one another. The distance between the nests in colony-breeding great crested grebes is at least two meters. Breeding colonies of grebes are always close to breeding colonies of other bird species. Most of these are black-headed gulls , but occasionally they breed with white-bearded terns and black-necked grebes .

Courtship behavior

The courtship of the great crested grebe is conspicuous and consists of a number of ritualized behavioral elements. The courtship starts in December in the wintering areas when the birds start to form pairs; it lasts for several months and only diminishes in intensity when the couples start nesting. The function of this behavior is the formation of couples and the maintenance of the couple relationship.

The penguin pose is one of the most noticeable courtship rituals of the great crested grebe: the couple stands up chest to chest on the water, the birds shake their heads and hit the water with their feet. During courtship, gifts in the form of food and nest material are given in the gift ritual. Males and females play identical or reversed roles. The “penguin dance” is usually preceded by the “head-shaking ceremony”, which in turn is initiated by the “maiden pose” or the “discovery ceremony”. In the maiden pose, a single bird uses far-reaching, harsh calls to indicate that it is looking for a partner. During the discovery ceremony, one bird approaches the other by diving just below the surface of the water, whereupon it slowly rises up over it in a ghost pose. The second bird faces him in a cat pose. The subsequent head-shaking ceremony is divided into three stages . In the first phase, the birds meet, lower their heads threateningly and come closer to one another, while they straighten up, spread their crests and collars and make a ticking sound. The beaks pointing downwards are shaken to the side. The second phase begins with a renewed straightening, in which the headdress feathers are less spread and the birds take turns shaking and rocking their heads. In the final third phase, one or both birds begin to pretend their plumage and lean back to pull one of the wing feathers up.

Agonistic behavior

Agonistic behavior is often observed in the great crested grebe during the breeding season. Elements of this behavior play a role both in pair formation and in defending the territory and the young.

In the event of an unexpected encounter with an unmated conspecific grebe often adopt a defensive pose in which the head and collar of the feathers are spread and the neck is stretched out horizontally. The beak points slightly towards the water. In the case of very excited birds, the wings are also slightly spread out and lowered. Attacking birds occasionally submerge and swim just below the surface of the water towards the disturbing bird. Fighting great crested grebes flap their wings, attack each other with beaked lashes and hit the water with their feet. Inferior rivals dive sideways, run across the surface of the water with flapping wings, and then dive or sometimes even fly up.

Mating and nest building

Great crested grebes build one or more temporary nests during courtship, which mainly serve as a mating platform. Mating is almost always preceded by building on the nest by both partners. When mating, one of the two great crested grebes lies on the platform with its neck and head straight and flat. The other partner bird first swims in the immediate vicinity of the nesting platform, then leaves the water and flaps its wings onto the partner lying on the platform.

Great crested grebes prefer to build their main nest on the outer edge of the siltation area of a body of water. The nest is either anchored to the ground or to submerged plants. Great crested grebes also build completely open swimming nests that are located in the middle of small or shallow water. Both parent birds are involved in building the nest. Nest building usually takes between two and eight days, but in extreme cases it can take 28 days. The nesting material is found in the immediate vicinity of the nest site. The base of the nest are reed stalks that are placed between plant stalks protruding from the water. The great crested grebes layer old leaves and fine roots on top of them. The main building materials, however, are reeds , cattails and sedges . As a rule, dry plant material from the previous year is used.

The nest protrudes between 3 and 10 centimeters above the surface of the water. The diameter of the nest is between 28 and 65 centimeters. The diameter of the nesting trough is between 12 and 22 centimeters.

Clutch and brood

Laying begins in Central Europe usually from April to the end of June. The eggs are laid in the morning or in the first half of the day. The laying interval between the individual eggs is usually 2 days. Freshly laid eggs are matt white. However, they soon take on a greenish and brownish color in the nest. The full clutch consists mainly of three to four eggs, but in exceptional cases, clutches of up to seven eggs are also possible.

The clutch is incubated by both parent birds alternately in a three-hour rhythm for 27 to 29 days. The brood begins with the laying of the first egg. The rotting nesting material has no heat generating significance. The temperature at the bottom of the nest hollow is 32 ° during incubation. According to Russian studies, great crested grebes leave their clutch alone for only 0.5 to 28 minutes. British studies, on the other hand, have found that the clutch is left between 10 and 492 minutes. If brooding grebes are disturbed by humans, they cover the clutch with nesting material and dive away from the nest. They reappear on the water surface at a distance of six to ten meters.

Rearing the young birds

The hatching of the chicks does not take place synchronously, but usually with an interval of one day. The chicks flee the nest and can swim themselves immediately and dive after six weeks. In the first two to ten weeks, however, they are mainly carried by the adult birds, hidden on their backs in their plumage, and even taken underwater when diving. If they swim independently, they stay in the first week of life within a radius of 50 to 100 meters from the nest. Older downy chicks roam more widely on the water.

During feeding, they usually sit on the back of one of the parent birds while the second feeds. The food is passed from beak tip to beak tip. The chicks' diet initially consists mainly of insects and their larvae as well as small fish. You are self-employed between the ages of 71 and 79 days and at this point you have swapped the dune dress for the youth dress.

Fledgling mortality rate

Carrion crows, magpies and marsh harriers in particular destroy clutches of the great crested grebes if they are abandoned for a while by the parent birds, for example after being disturbed by humans. The change in water level is another reason why clutches are lost. According to various studies in Great Britain, continental Europe and Russia, between 2.1 and 2.6 downy chicks hatch per clutch. The downy chicks are also eaten by large predatory fish such as pike. Some of the downy chicks starved to death because they lost touch with their parent bird. Unfavorable weather conditions also have a negative effect on the number of young birds that fledge.

Endangerment and existence

After the stock of great crested grebes declined significantly as a result of hunting and an impairment of the habitat, the European stock of great crested grebes has risen sharply since the late 1960s and early 1970s. At the same time, the species has significantly expanded its area. The increase in the population and the expansion of the area are mainly due to the eutrophication of the waters by increasing the nutrient input and thus - at least initially - a better food supply, especially for white fish . At the same time, the population increase was favored by the creation of fish ponds and reservoirs. Since the 1990s, the population development has stagnated or in some regions has even declined. Overall, the population development in Central Europe is very uneven.

Investigations on quarry ponds in the Danube Valley in Bavaria showed that the breeding success of quarry ponds that were closed for recreational use for nature conservation reasons was twice as great as on lakes with recreational use. At closed lakes, an average of 1.8 young birds fledged per breeding pair, while with recreational use by humans, only 0.9 fledged young birds on average. Troubled quarry ponds are also used twice as often for breeding as those with human use.

The European population is between 300,000 and 450,000 breeding pairs. The largest population is in the European part of Russia, where between 90,000 and 150,000 breeding pairs occur. Countries with more than 15,000 breeding pairs are Finland, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Sweden and the Ukraine. Between 63,000 and 90,000 breeding pairs breed in Central Europe. The summer herds also contain a large proportion of non-breeders.

The great crested grebe is one of the species that will be particularly hard hit by climate change. A research team working on behalf of the British Environmental Protection Agency and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds to study the future distribution of European breeding birds on the basis of climate models assumes that the range of this species will change significantly by the end of the 21st century . According to this forecast, the distribution area will shrink by about a third and at the same time shift to the northeast. Possible future distribution areas include the Kola Peninsula and the northernmost part of western Russia. In contrast, a large part of the range on the Iberian Peninsula, on the northern Mediterranean coast and in France is lost. The Central European distribution area becomes significantly more patchy.

Great crested grebes and humans

The protection of the great crested grebe was the founding goal of a British animal welfare association in the 19th century , which later became the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). Bonnet bellows , especially the dense, silky plumage of the chest and abdomen, were very often used in the fashion industry at that time . Milliners set forth collars, hats and muffs from the fur-like pieces. Due to the protection efforts of the RSPB, the species could be preserved in Great Britain.

Since fish are its main source of food, the great crested grebe has always been persecuted. The greatest threat comes from anglers as well as bathers and water sports enthusiasts, who are increasingly visiting small bodies of water and their shorelines, which is why the bird is becoming increasingly rare, despite the legal nature protection.

supporting documents

literature

- Hans-Günther Bauer, Einhard Bezzel and Wolfgang Fiedler (eds.): The compendium of birds in Central Europe: Everything about biology, endangerment and protection. Volume 1: Nonpasseriformes - non-sparrow birds. Aula-Verlag Wiebelsheim, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89104-647-2 .

- Einhard Bezzel: birds. BLV Verlagsgesellschaft, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-405-14736-0 .

- Jon Fjeldså : The Grebes. Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-850064-5 .

- VD Il'ičev & VE Flint (eds.): Handbook of birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden 1985, ISBN 3-89104-414-3 .

- Lars Jonsson : The birds of Europe and the Mediterranean - Kosmos-Naturführer , Franckh-Kosmos Stuttgart 1992/1999, ISBN 3-440-06357-7 .

- André Konter: Grebes of our world , Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2001, ISBN 84-87334-33-4 .

- Günther Niethammer (Hrsg.): Handbook of the birds of Central Europe. Volume 1: Gaviformes - Phoenicopteriformes. Edited by Kurt M. Bauer and Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim , Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Wiesbaden 1966.

- Paul Sterry (Editor): The Encyclopedia of European Birds. Tosa, Vienna, 2003. ISBN 3-85492-813-0 .

- Lars Svensson, Peter J. Grant, Killian Mullarney, Dan Zetterström: The new cosmos bird guide . Kosmos, Stuttgart, 1999. ISBN 3-440-07720-9 .

Web links

- Podiceps cristatus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 8 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings on Podiceps cristatus in the Internet Bird Collection

- Great crested feathers

- Large series of photos: courtship, brood and rearing of the young

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bezzel, p. 72.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 271.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 272.

- ↑ Collin Harrison, Peter Castell: Young birds, eggs and nests of birds in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. 2nd Edition. Aula, Wiebelsheim 2004, ISBN 3-89104-685-5 . P. 32 f.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 272.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 283.

- ↑ a b c Wissenschaft-Online-Lexika: Entry on Lappentaucher - Haubentaucher in the Lexikon der Biologie , accessed May 20, 2008.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 275.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 274.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 275.

- ↑ Martin Flade: The breeding bird communities of Central and Northern Germany - Basics for the use of ornithological data in landscape planning . IHW-Verlag, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-930167-00-X , p. 552.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 277.

- ↑ Bauer et al., P. 187.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 283.

- ↑ Bauer et al., P. 187.

- ↑ Bauer et al., P. 187.

- ↑ Bauer et al., P. 187.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 283.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 281.

- ^ Wissenschaft-Online-Lexika: Entry on gift ritual in the Lexikon der Biologie , accessed May 20, 2008.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 278.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 278 f.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 280.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 280.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 280.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 280 f.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 281.

- ↑ Collin Harrison, Peter Castell: Young birds, eggs and nests of birds in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. 2nd Edition. Aula, Wiebelsheim 2004, ISBN 3-89104-685-5 , p. 32.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 282.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 282.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 282.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 283.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 283 f.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 283 f.

- ↑ Il'ičev & Flint: Handbook of Birds of the Soviet Union - Volume 1: History of exploration, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes . 1985, p. 283 f.

- ^ Bauer et al., P. 186.

- ^ Bauer et al., P. 186.

- ↑ Franz Leibl, Wolfgang Völk: Recreational use influences the breeding settlement and breeding success in the great crested grebe Podiceps cristatus . The Bird World 131: 245–249.

- ↑ Bauer et al., P. 185.

- ^ Brian Huntley, Rhys E. Green, Yvonne C. Collingham, Stephen G. Willis: A Climatic Atlas of European Breeding Birds , Durham University, The RSPB and Lynx Editions, Barcelona 2007, ISBN 978-84-96553-14-9 , P. 37.

- ↑ Nature Conservation Today - Issue 1/01 of January 26, 2001 ( archive link ( Memento of the original from April 18, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and remove then this note. )