Polish-Russian War 1609–1618

| date | 1609 to 1618 |

|---|---|

| place | western Russia (Smolensk, Moscow) |

| Casus Belli | internal weakness of Russia in the time of turmoil , claim of the Polish king to the throne of the tsar |

| output | Smaller Polish success, but Russia can maintain its independence from Poland |

| Territorial changes | Russian assignment of territory (including the city of Smolensk) to Poland |

| consequences | Treaty of Deulino |

| Peace treaty | 1618 |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Tsar Vasily IV. Ivanovich Shuisky |

|

| losses | |

|

unknown |

unknown |

The Polish-Russian War 1609-1618 was a war between the Kingdom of Poland-Lithuania and Tsarist Russia . The war began with an offensive by Poland under the leadership of the Polish King Sigismund III. Wasa with the aim of securing the crown of Russia for itself and ended in 1618 with the Treaty of Deulino , in which Poland-Lithuania territorial concessions were made, which thereby reached its greatest territorial expansion. The Russian Empire, however, was able to secure its independence.

prehistory

At that time Russia was in the so-called Time of Troubles , the Smuta , which lasted from 1598 to 1613. The reason for this was the extinction of the ruling line of the Moscow Rurikids , which put the tsarist rule in limbo. This period was characterized by general anarchy , broken power relations and a temporary interregnum phase. Before 1610 the Russian swindlers Pseudodimitri I and Pseudodimitri II succeeded in seizing power in Russia with the support of Polish magnates , but without being able to hold the throne permanently, as they did not enter into a coalition with the high nobility and foreigners, especially sought to realize ideas borrowed from the Polish model. When the fake Dmitry got married with the Catholic Marina, contrary to tradition and belief, a Moscow uprising swept him away. The good relations with the Polish archenemy, who in their opinion were incredulous , were too obvious , and the harbingers of Europeanization were too abrupt.

From 1610 to 1617 the tsarism of Russia, called " Moscow " in Europe at the time, was also in a parallel war with the Kingdom of Sweden ( Ingermanland War ), which was trying to secure the Moscow throne for itself.

The Polish King Sigismund III. Wasa , who had also been King of Sweden until his deposition in 1599, did not want to cede the Moscow throne to his Swedish enemies and decided to intervene. The basis for this intervention made the Treaty of Tushino from February 4, 1610 between the Polish king and against the Russian Tsar Vasily IV. Shuisky set boyars . In this treaty, both parties agreed to crown the son of the Polish king, Władysław , as tsar and to limit the tsar's power; however, the contract was never implemented.

Course of war

Polish occupation of Moscow and Russian interregnum

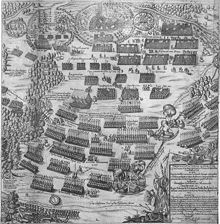

The armed conflicts began in the autumn of 1609 when a Polish army led by the Polish king began a long siege of the Russian city of Smolensk . After a second Polish army defeated an outnumbered Russian army at the Battle of Klushino on June 24th July / 4th July 1610 greg. was able to defeat, Tsar Vasily IV was overthrown on July 17, 1610 by domestic political opponents and shorn to a simple monk. In addition to the general anarchy in the Moscow Empire, there was also an interregnum phase that formed the climax of the Smuta.

After this defeat, Moscow had nothing more to oppose to the Polish army, led by Stanisław Żółkiewski , whereupon they captured Moshaisk , Wolokolamsk and Dmitrov . At the end of July 1610, the Polish army reached Moscow .

In the meantime, after the fall of the tsar, a council of seven boyars (called the Duma) was set up in Moscow to represent the new Moscow leadership. As contractually agreed, the council immediately elected Prince Władysław, the son of the Polish king, as the new Moscow tsar. When this council went to the Polish camp near Smolensk to carry out the coronation of the new tsar, the Polish king who was present finally had the council arrested in April 1611 after lengthy negotiations and deported to Poland - as a measure of repression for the Moscow uprising that had broken out in the meantime was intended.

The Polish king wanted to rule over the Moscow Empire himself in order to be able to maintain a good starting position for a renewed Polish-Swedish personal union that he was striving for. A possible historical compromise between Russians and Poles in view of the Russian plight failed. The plans were aimed at Russia's dependence on Poland. The coronation of a Catholic king of Poland as Russian tsar was just as impossible as the conversion of a Polish king to the Russian Orthodox faith. The tsar's crown demanded by the king was something completely different from the election of his son as tsar, in the expectation that he, as the orthodox tsar, would later not be elected as the successor of his father, the Polish king.

Russian popular uprisings

In view of this, the pro-Polish faction among the boyars fell away from the Polish king. Thus, several provisional Russian counter-movements to the isolated Polish government in Moscow formed one after the other. The popular uprising was supported by the Patriarch Hermogenes , who, as imperial administrator and Interrex, stirred up anti-Catholic emotions and openly exposed the hatred of the occupiers. From January 1611 onwards, important cities (including Nizhny Novgorod , Vologda ) of the Moscow Empire formed associations for the reconquest of Moscow. The uprising of Moscow citizens that broke out in Moscow on February 13, 1611 marked the beginning of the decline of Polish rule in the Moscow Empire, which was accompanied by religious repression.

In order not to dissipate their forces over an overly large area, the Polish garrison decided to claim only the core of the city, namely the Kremlin and the adjacent neighborhood of Kitai-Gorod . The Polish king could not come to the aid of the isolated Moscow garrison, as he was bound with his army until the beginning of 1611 during the siege of Smolensk .

The first wave of uprisings was successfully suppressed by the 3,000-strong Polish garrison. During the first uprising, part of Moscow was destroyed by fire.

On March 19, the uprising broke out again, which in turn was suppressed in street fighting by the Polish garrison . The city contingent, which had been drawn up since January 1611, attacked occupied Moscow on March 24, 1611, but was again thrown back by a Polish counterattack. After the storming failed due to the lack of siege artillery, this Landwehr (opolčenie) now besieged the Moscow Kremlin . The line-up of this group was mixed up heterogeneously. It consisted of townspeople, Cossacks and various other groups. This intermingling posed a problem for the discipline in the siege camp. So the 1st contingent broke up again on June 27, 1611, as the Cossacks present refused to recognize a unified authority. On June 13, 1611, the Russian city of Smolensk, which had been besieged for 20 months, fell into Polish hands.

At that moment the Russian state seemed to be on the verge of final disintegration. However, in the late summer of 1611 a decisive patriotic counter-movement began in the unoccupied areas, which led to the formation of a second Landwehr detachment in Nizhny Novgorod. This movement expressed the will of the entire Russian people to want to restore public order and a legitimate central authority in order to overcome the ongoing chaos in the Moscow state. In essence, this contingent consisted of armed city dwellers, but this time emphasis was placed on discipline in the troops. Up to this point in time, the Polish garrison could be increased to 4,000 men through a one-off relief.

Russian siege of Moscow

The second contingent reached the gates of Moscow in July 1612. The Landwehr contingent comprised between 25,000 and 30,000 men with various armaments and around 1,000 riflemen. Between August 22nd and August 24th, 1612 the Russian Landwehr contingent fought against an arrived Polish relief army. After the initial successes of the Poles, the Russians succeeded in repelling the Polish attacks and preventing Polish relief from the fortress.

The Polish garrison withstood the Russian siege for a total of 19 months, but had to surrender and withdraw on October 25, 1612 in front of Kusma Minin and Dmitri Poscharski's army contingent due to hunger and the failed Polish relief . Nevertheless, in 1612 Polish troops occupied large areas in the west of the Moscow Empire.

End of the Russian interregnum

Despite the victory in Moscow, the Swedes were still in northwestern Russia with Novgorod as their main garrison. The Swedish King Charles IX. again demanded the tsar's crown for Prince Karl Filip of Sweden in exchange for Novgorod. However, a foreign succession to the throne was no longer an issue. Russia was looking for a national, orthodox tsar. In 1613, the newly formed Russian estates in Moscow decided to elect the 16-year-old Michael Romanov , a candidate for the nobility, as Russian tsar, who at the time was staying in a monastery near Kostroma . The young man appeared to be a sufficiently weak tsar, from whom one did not have to fear a tyrannical autocracy . The electoral assembly, which constituted itself as a whole country, was represented by almost all social classes and groups with the exception of the non-free and the ruling peasants. In the two and a half years of the interregnum from 1610 to 1613, it was precisely these groups who had resisted foreign intervention and struggled to maintain an administration, but conditions were not imposed on Tsar-elect Mikhail before the election. This ended the interregnum phase in the Russian Empire and the remaining Polish troops withdrew to the Polish border.

Outcome of the war

Until 1617, with the exception of an unsuccessful Russian attempt to retake Smolensk in 1615, major combat operations were not carried out, as the limited resources on both sides did not permit major acts of war and thus a military stalemate arose. In addition to Moscow's general exhaustion, this was also due to the fact that the financially weak Polish king had to maintain expensive mercenaries because the republic's proper contingent was not even available to fulfill the pacta conventa .

In the Polish Republic itself, after the withdrawal of the Moscow garrison in 1613, chaotic conditions threatened to return. The borders in the north, east and south were also unsecured. A change suddenly occurred when, in the spring of 1616, the Szlachta decided, with rare unanimity, to want to enforce peace with military pressure.

Thus the large-scale Habsburg mediation attempt that had been prepared since 1612 also failed. The Habsburg Monarchy feared above all that in the event of a Polish victory, with the takeover of the Moscow Tsar's throne, the Polish Vasa House would have gained a preponderance with which it could also win back the former Swedish crown and, as a result, would have created a north-eastern European super monarchy .

After long preparations, the Polish Crown Prince Władysław, who did not want to give up his claims to the Russian throne, began a new campaign to Moscow in the autumn of 1617. The Polish troops advanced towards Moscow via Vyazma and the smaller Russian border fortresses. The Polish army then united with a Ukrainian Cossack army led by Ataman Sahaidachnyj , which undertook an unsuccessful assault on Moscow. Then the united army marched to the Trinity monastery in Sergiev Posad to take this important religious center. However, the siege of the fortified monastery failed due to the resistance of the monks and the stationed Strelitzen troops. The Moscow Empire itself was too weak at the time to face and defeat the Polish army in an open field battle.

An end to the fighting had also become urgent for Poland-Lithuania, as the republic had got into difficulties with the Ottomans because of the Cossack and Moldova policy and had to fear renewed invasions by the Swedes.

Armistice and the consequences

In 1618 the Treaty of Deulino (Deulino is a town near Moscow) was signed, in which Poland-Lithuania was granted the area around Smolensk and Severien , which the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had lost to Russia in the treaty of 1522. In addition, a 14½-year armistice was agreed between the warring parties. After the treaty, Poland-Lithuania again assumed a powerful position in the Ruthenian countries. In addition, a mutual exchange of prisoners of war was agreed in the contract. The Polish prince did not have to give up the Russian throne de jure .

This treaty gave Moscow the much-needed ceasefire in order to be able to regenerate internally. It took until the mid-17th century to overcome the 1560-1620 Depression. The power-political restraint that exhausted Moscow imposed on itself towards Poland-Lithuania was only interrupted from 1632 to 1634 when, as a result of a Polish interregnum after the death of Sigismund III. Wasa in league with the Swedes Gustav Adolf wanted to recapture the territories lost in 1618 without success.

The class consciousness developed during the time of the Smuta disappeared without a sound in 1622 after the emergency situation subsided in favor of the connection to the old autocracy. This process was supported by the Church, for whom tsarist power was traditionally a necessary addition to its own spiritual authority. The small and middle service nobility needed the tsar in turn as protection from the powerful high aristocracy. The Russian people, deeply rooted in the consciousness of autocracy, focused on security and prosperity after the chaotic times of the Smuta, and welcomed a strong hero in the person of the Tsar.

Others

Death of the Patriarch Hermogenes

The leader of the Russian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Hermogenes , was imprisoned by the Polish side during the siege of Moscow in 1611 after issuing appeals against the Poles and the Cossacks. Although he was closely guarded by the Polish garrison in the Kremlin , he continued to run it. Since he did not want to cease his secret activities, the Poles threw him into a dungeon, where he starved to death in February 1612. In 1913 he was canonized as a martyr by the Russian Orthodox Church.

The legend of Ivan Sussanin

According to legend, after the liberation of Moscow, Mikhail Romanov traveled to Kostroma to be crowned tsar. It is said that plundering Cossacks intended to seize him there. To save his master, a farmer named Iwan Sussanin led the Cossacks on a wrong path into deep forests, for which he was murdered. The composer Michail Glinka dedicated the opera A Life for the Tsar to this legend . The village of Sussanino and Sussanin Square in the city of Kostroma were named after the hero.

Russian holiday

To commemorate the liberation of Moscow, November 4th was celebrated as a national holiday in the Russian Empire. The day was considered the day of the people-initiated re-establishment of the Russian state, which had previously ceased to exist. After the Bolsheviks came to power , the holiday was abolished because it was too close to the celebrations of the anniversary of the October Revolution and to commemorate the rule of the Romanovs. In 2005 , Russian President Vladimir Putin reintroduced the old public holiday under the name “ National Unity Day ”.

Individual evidence

- ^ Goehrke / Hellmann / Lorenz / Scheibert: World History - Russia, Volume 31, Weltbild Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1998, p. 143.

- ↑ http://www.retrobibliothek.de/retrobib/seite.html?id=113965 .

- ↑ Lothar Rühl: Rise and Fall of the Russian Empire , Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-421-06534-9 , p. 136.

- ^ Goehrke / Hellmann / Lorenz / Scheibert: Weltgeschichte - Russland, Volume 31, Weltbild Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1998, p. 144.

- ↑ a b Manfred Hellmann: Handbuch der Geschichte Russlands, Volume I bis 1613 , Hiersemann Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, p. 1055.

- ↑ Valentin Gitermann: History of Russia first band, Frankfurt am Main in 1987, Atheneum Publishers, S. 250th

- ↑ Manfred Hellmann: Handbuch der Geschichte Russlands, Volume I bis 1613 , Hiersemann Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, p. 1056.

- ↑ Manfred Hellmann: Handbuch der Geschichte Russlands, Volume I bis 1613 , Hiersemann Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, p. 1063.

- ↑ Lothar Rühl: Rise and Fall of the Russian Empire , p. 138.

- ^ Goehrke / Hellmann / Lorenz / Scheibert: World History - Russia, Volume 31, Weltbild Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1998, p. 146.

- ↑ Representatives of 50 cities, the nobility, high officials, the church and, for the first time, the Russian Cossacks: Lothar Rühl: Rise and decline of the Russian Empire , p. 137.

- ^ Klaus Zernack: Handbuch der Geschichte Russlands , Volume 2: 1613-1856, from Randtstaat zur Hegemonialmacht, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-7772-8618-4 , p. 45.

- ↑ a b Klaus Zernack: Handbuch der Geschichte Russlands , Volume 2: 1613-1856, from Randtstaat zur Hegemonialmacht, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-7772-8618-4 , p. 46.

- ^ Goehrke / Hellmann / Lorenz / Scheibert: World History - Russia , Volume 31, Weltbild Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1998, p. 160.

- ↑ Valentin Gitermann: History of Russia first band , Frankfurt am Main in 1987, Atheneum Publishers, S. 250th

- ↑ Valentin Gitermann: History of Russia first band , Frankfurt am Main in 1987, Atheneum Publishers, S. 257th

literature

- Hans-Joachim Torke: Lexicon of the History of Russia , Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-406-30447-8 .

- Günther Stökl : Russian history. From the beginnings to the present (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 244). 5th enlarged edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-520-24405-5 .

- Klaus Zernack: Handbuch der Geschichte Russlands, Volume II 1613-1856 - From the peripheral state to the hegemonic power , Hiersemann Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-7772-8618-4 .

- Manfred Hellmann : Handbook of the History of Russia, Volume I Until 1613 , Hiersemann Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-7772-8618-4 .

- Valentin Gitermann: History of Russia 1st volume , Frankfurt am Main 1987, Athenäum Verlag, ISBN 3-610-08461-8 .