Naval Battle of Lepanto

| date | October 7, 1571 |

|---|---|

| place | Strait of Lepanto (Greece) |

| output | Holy League victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Don Juan de Austria |

|

| Troop strength | |

| 255 galleys, 34,000 soldiers, 46,000 sailors and rowers | 206 galleys and 6 galleys , 28,000 soldiers, 40,000 sailors and rowers |

| losses | |

|

approx. 30,000 dead. |

8,000 dead |

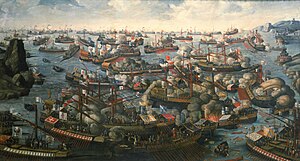

The naval battle of Lepanto took place on October 7, 1571 in the Ionian Sea in front of the entrance to the Gulf of Patras near Lepanto (Greek Nafpaktos ) in what is now Greece . The Christian Mediterranean powers, organized under Pope Pius V , with Spain at their head, achieved a surprising victory over the Ottoman Empire here . Commander-in-chief on the side of the Holy League from 1571 was Don Juan de Austria , on the Ottoman side Kaptan-ı Derya Ali Pascha , who died in the battle. It is the sea battle with the most dead in one day.

prehistory

In 1570 the island of Cyprus, controlled by the Republic of Venice , was conquered by the Ottomans under Piyale Pascha and Lala Kara Mustafa Pascha . Under the impact of this event, the Christian powers sought the mediation of Pope Pius V . the direct confrontation with the Ottoman Empire in the eastern Mediterranean. On August 1, 1571, the last Venetian garrison of Famagusta fell to the Turks after a four-month siege , who cruelly executed the commander Marcantonio Bragadin .

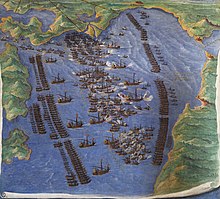

From July to mid-September 1571, the fleet of the Christian League assembled in the port of Messina under the command of Don Juan d'Austria . Of a total of 213 ships, the Venetians made up the largest contingent with 105 galleys and 6 galleys . On the morning of September 16, the Christian fleet set out and on September 24 circled the heel of Puglia .

In 1571 the entire Ottoman navy comprised 500–600 galleys with a crew of more than 150,000. The Kapudan Pasha in the western sea, Müezzinzade Ali , immediately started raiding against fortified Venetian bases in the Ionian Sea , and a strong squadron even advanced to Zara in September . After the reported arrival of the Christian fleet, the Ottoman fleet withdrew across the Bay of Naupaktos into the Gulf and gathered 255 galleys and galleons , with a crew of around 80,000 (including 34,000 soldiers) on board. At the western entrance of the Gulf of Patras , between the island of Oxia and Cape Skropha, the Christian fleet sailed through and was then put to battle by the Ottoman fleet, which had left Lepanto (Naupaktos) on the night of October 6th. The battle was fought south of the former island of Koutsilaris in front of the entrance to the Gulf of Patras. Before the battle, the ships of the Holy League formed at the small island of Oxia in order to attack the enemy fleet in a strategic group.

course

On the morning of October 7, 1571, the two fleets headed towards each other in calm seas and clear visibility. Don Juan de Austria, on the galley La Real (“The Royal”), led 206 galleys into battle. 40,000 sailors and rowers and 28,000 soldiers were subordinate to him. Most of the galleys had a large cannon on the bow and four smaller flanking guns. The Sultan's fleet was even larger: it comprised a total of 255 galleys with cannons and 18 mostly smaller ships.

Don Juan organized a parallel battle line several kilometers wide with the Christian fleet. In the center of the Christian line were 64 galleys under Don Juan, the flagship La Real was flanked on both sides by the galleys of the Venetian vice-commander Sebastiano Venier and the papal admiral Marcantonio Colonna . Other Spanish subordinates in the middle were Gil d`Andrada and Sancho de Leyva. On the left northern wing, which leaned against Cape Skropha, the Venetians led 53 galleys under the command of Provveditore Agostino Barbarigo , and Antonio Canale and Marco Querini as leaders of the left and right flanks. The right wing under Giovanni Andrea Doria , 54 galleys strong, could not be formed quickly enough when the battle opened. The vanguard of the Sicilian squadron under Juan de Cardona y Requesens withdrew and closed the gap between the center and the wing extended to the south under Doria. Behind the front, a fourth squadron under the command of the Marques de Santa Cruz , consisting of 38 galleys, was placed as a reserve.

The front was thus divided in its entirety into three main sections: a southern, a central and a northern section. The six great Venetian galeas were set up in the north and in the center. They were an important reason for the victory of the Holy League, as they could fire projectiles of larger caliber with their cannons and were extremely difficult to board and capture because of the high ship's side. They were not only equipped with nine larger cannons at the bow, but - in contrast to the galleys - with guns on the sides of the ship. As a result, they were able in close combat to shoot ships that were going alongside for boarding.

Müezzinzade Ali Pascha, the commander-in-chief of the Turks, had also divided his ships into three squadrons and a reserve unit. His battle line was more than 1,000 meters longer than that of the Christians. Ali Pascha himself commanded the center, as did Don Juan de Austria that of the Holy League. The right wing was commanded by Ali Şuluk Reis, later better known in the West as Mehmed Sirocco, and the left wing was led by Uludsch Ali Pascha, Vice Commander of the Ottoman fleet .

At 9:30 a.m., after the service for the fleet, don Juan fired a signal cannon on board his flagship Real . Ali Pasha replied in the same way from on board his flagship, the Sultana . Then the battle began. At ten o'clock there was a light westerly wind and both north wings were moving forward. At 10:20 a.m., two galeasses took up position in front of the central Christian squadron. At 10:30 a.m., two more Venetian galleries, located in front of the north wing, opened fire. With the third shot they sank a Turkish galley. The firepower of the galeas made deep breaches in the hostile order of battle. In the center and especially on the north wing, many Turkish galleys went off course, their rowers were either wounded or dead.

At 10:40 a.m., the squadrons collided on the north wing and the galleys became entangled. Most Christian soldiers were armed with arquebuses , heavy firearms whose lead bullets could penetrate even strong armor. Most Turkish soldiers, however, still fought with bows and arrows. Since the narrow gulf left no space for extensive maneuvers, there was basically no strategy or tactics in hand-to-hand combat, ship to ship and man to man.

At 11 a.m., five Turkish galleys circled the Venetian flagship, and Turkish soldiers boarded the Republic's flagship, the San Marco. Admiral Barbarigo, who had opened the visor of his helmet to make himself better heard, was fatally wounded by a Turkish arrow in the right eye. When they saw the enemy commander fall, the Turks stepped up their assault on the galley. The Venetians were only able to hold their ship with great difficulty until a galley from the reserve squadron came to their aid. The battle raged on along the entire line of battle until the league gradually managed to push the Turkish galleys against the nearby cliffs. Many Turks jumped overboard and tried to swim to the country.

At the same time, Ali Pasha ordered the Sultana to take a direct course for Don Juan's flagship, La Real . Within a very short period of time, over 30 galleys crowded together in a very small space. The Sultan's elite warriors, the Janissaries , fought on the front line against Don Juan's body troops. Don Juan himself was injured in the leg while fighting off the boarding troops. His bodyguards pulled him out of the fray and brought him to safety. The Venetian deputy commander, Sebastiano Venier, himself only recently demoted by Don Juan de Austria, rushed to the aid of the commander-in-chief. Hundreds of fighters were now involved in bloody hand-to-hand combat. The Spaniards succeeded in pushing back the Turks. Even rowing slaves are said to have been released and armed to hold the ship when the Turks attacked.

The first troops boarded the Sultana for their part . Ali Pasha was hit in the forehead by a bullet. Thereupon the resistance of his troops waned and the Sultana was conquered. Ali Pasha's head was cut off and held up so that it could be seen from afar.

A squadron from the Turkish South Wing was still trying to come to the aid of the center, but it was too late. At 1:20 p.m. all the Turkish galleys in the center of the battle line had been captured or sunk, and innumerable soldiers of the Sultan had fallen.

The situation on the south wing had meanwhile developed to the advantage of the Turks. Here Uludsch Ali had succeeded in gradually wiping out the associations of the Holy League opposing him. His battle-hardened men were able to put the local Christian armed forces, mainly Maltese, on the defensive and ultimately capture the Maltese flagship . The commander-in-chief of the Maltese fleet was killed, as were many other knights of the Order of Malta. Don Juan received news of the critical situation on the south wing and immediately swung a large unit onto the south wing. When Uludsch Ali saw this, he knew that the battle was lost. In order not to be trapped, he gave the order to break through the ranks of the enemy. With about 30 ships he managed to break away and sail with his association around the Peloponnese to Constantinople , where he handed over the captured large Maltese flag to Sultan Selim II . He received the honorary name "Kilic" (sword) from the Sultan and was then known as Kilic Ali Pascha .

After five and a half hours of fighting, the battle for the Holy League was won. 117 enemy galleys were captured and more than 30,000 enemy soldiers killed. The allies numbered 8,000 dead, 4,800 of them from Venice alone, and around 8,000 wounded. The Holy League only lost 13 of its ships. The Ottoman fleet put 30 of their ships aground themselves, and over 60 others were sunk. 12,000 Christian rowing slaves were freed from the captured galleys. This broke the nimbus of the invincibility of the Ottoman Mediterranean fleet.

Consequences of the battle

The victory of the Holy League was very important psychologically, but could not be exploited as there was insufficient land army available. The battle was very important in that with this victory the myth of the invincible Ottomans was broken.

On the first anniversary of the Muslim defeat on October 7, 1571, the feast of the Rosary was introduced in 1572 to underline the intercession of the Virgin Mary during the battle. Victory Day remains the Catholic Day of Remembrance of Our Lady of Victory , later renamed Our Lady of the Rosary.

The Venetians wanted to attack Constantinople directly to take advantage of the enemy's current weakness. But Philip II did not want to know anything about a decisive battle against the Turks. In May 1572, Pius V, the most energetic supporter and supporter of the alliance, died. The alliance finally broke up. Venice now faced the Ottoman Empire again alone. Now they sought a compromise with the Sublime Porte , also out of fear of a campaign of revenge by the Turks and in view of the mutual dependence on trade issues .

The Ottoman fleet had already made up for its losses within a year, built over 150 new war galleys and again had a total of 250 galleys . The commander-in-chief of the fleet also had over 20,000 arquebuses made. The Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha was unimpressed by the defeat when he dictated the difference between your and our defeat to the Venetian ambassador in Constantinople :

- In snatching the Kingdom of Cyprus from you, we severed your arm. By defeating our fleet, you only shaved off our beards. The arm doesn't grow back, but the beard grows all the thicker.

The Ottomans conquered Tunis as early as 1574 . Nevertheless, the Ottoman dream of a world power at sea was destroyed with the defeat of Lepanto. The loss of many experienced commanders, captains and seamen on the Turkish side could not be compensated for for many years.

Venice concluded a separate peace with the sultan in March 1573. In order to secure the old privileges in the Levant trade, the Venetians made far-reaching concessions despite the victory of Lepanto. The republic released all Turkish prisoners without paying a ransom and paid the sultan considerable war compensation. Cyprus remained Turkish.

The battle of Lepanto led to a clearing up of the spheres of influence in the Mediterranean. The Ottomans then limited themselves to securing their supremacy in the eastern part, while Spanish, Maltese and Italian fleets divided up the western Mediterranean - however, until the early 19th century, they were threatened by the corsairs of the barbarian states in North Africa, those from the Ottoman provinces there emerged.

Representations in literature and fine arts

The news of the unexpected victory spread like wildfire through Christian Europe. For many victory celebrations in the participating countries, writers created texts and (as occasional or commissioned poetry ) in particular praise poems and small pens ( epyllia ) on victory ( epinicia ) in a short time . Pietro Gherardi (Petrus Gherardius) was one of the first to collect several of these texts in 1572 under the title In foedus et victoriam contra Turcas iuxta Sinum Corinthiacum (Venice 1572). In the same year, Luigi Groto published Trofeo della vittoria sacra (Venice 1572) and the anonymous collection Raccolta di varii poemi Latini, Greci, e Volgari (Venice 1572). Juan Latino , professor of Latin in Grenada and the first black African with literary success in a European language, published an Austrias Carmen (poem on Juan de Austria ) in two books in 1573 .

The Venetian painter Paolo Veronese created an oil painting probably a year after the battle, which now hangs in the Galleria dell'Accademia in his hometown. In the lower part it shows the ships wedged together in the bay and above a heavenly event: Saint Peter , Rochus von Montpellier , Saint Justina , on whose commemoration day the battle took place, and Mark , the patron saint of Venice (recognizable by his lion ), implore the Virgin Mary to give victory to the Christian fleet. This request is heard, because on the right an angel is already starting to throw fire arrows at the Ottoman fleet. In another allegorical painting that can be seen in the Doge's Palace , Veronese placed Sebastiano Venier , the commander of the Venetian fleet, at the center: he kneels before St. Justina, accompanied by St. Fides and St. Mark.

Miguel de Cervantes took part in the battle as a simple soldier. He received three gunshot wounds, two in the chest and one in his left hand, which was permanently disfigured. His experiences have flowed into his novel Don Quixote .

The writer Bruno Frank, on the other hand, treats the naval battle in his novel Cervantes from 1934 in two chapters and beyond that as a preview and review in the adjacent chapters.

In the monastery church in Speinhart, around 1698, the Italian artist Bartholomeo Lucchese created one of the earliest frescoes on the battle of Lepanto in southern Germany. The picture occupies the center of the ceiling of the so-called Rosary Brotherhood Chapel. The artist may have used a copperplate or woodcut as a template.

An impressive depiction of the naval battle at Lepanto is a monstrance designed in 1708 by the Augsburg goldsmith Johannes Zeckl for the Congregation in the Asamkirche Maria de Victoria in Ingolstadt , which depicts the battle in an “unprecedented wealth of detail”.

In the parish church of the Assumption of Mary in Prien am Chiemsee , a baroque church, built 1734–1738, there is a monumental ceiling painting by Johann Baptist Zimmermann , created 1738–1740, depicting the naval battle of Lepanto.

In the pilgrimage church of Maria Sondheim on the outskirts of the town of Arnstein / Lower Franconia, a ceiling painting shows the naval battle of Lepanto.

In a side chapel of the parish church of Scheibbs in Lower Austria, a ceiling painting shows the naval battle of Lepanto.

In the church of Santa Maria Assunta in Civita (Calabria, Italy) there is a painting by the Albanian iconographer Iosif Droboniku, which depicts the naval battle of Lepanto.

The subject was thematized in 2001 by the American painter Cy Twombly in a cycle of twelve large-format abstract pictures. This cycle is exhibited in the Brandhorst Museum in Munich.

Gilbert Keith Chesterton published a poem about the naval battle called Lepanto in 1911.

The composer Andrea Gabrieli composed a three-part madrigal Asia Felice - Et io più all'hor felice Affrica - Felice Europa anch'io for the victory celebration in Venice.

Commemoration

The battle was used by Venice for state propaganda, the anniversary of the battle became one of the most important holidays of the republic.

To this day, every year on the anniversary of the battle, the members of the noble families involved in the battle from all over Europe meet in the Vatican to commemorate this event.

literature

- Niccolò Capponi: Victory of the West. The Story of the Battle of Lepanto. MacMillan, London 2006, ISBN 1-4050-4588-4 .

- Stefan Hanß: The material culture of the sea battle of Lepanto (1571): materiality, mediality and the historical production of an event . Ergon, Würzburg 2017.

- Felix Hartlaub : Don Juan d'Austria and the Battle of Lepanto [Dissertation Berlin 1940], Edition Mnemosyne, Neckargemünd & Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-934012-30-1 .

- Angus Kostam: Lepanto 1571. The Greatest Naval Battle of the Renaissance . Osprey Publishing. Wellingborough 2003, ISBN 1-84176-409-4 .

- Roger Crowley : Empires of the Sea. The Siege of Malta, the Battle of Lepanto, and the Contest for the Center of the World. New York 2009; German translation under the title: Decision in the Mediterranean. Europe's naval war against the Ottoman Empire 1521-1580 . Theiss, Stuttgart (2009) 2., corr. 2012 edition (320 pages).

- James Harper (Ed.): The Turk and Islam in the Western Eye, 1450-1750. Farnham, Surrey, UK 2011.

- Simona Mammana: Lepanto. Rime per la vittoria sul Turco. Regesto (1571-1573) e studio critico. Rome 2007.

- Wolfram zu Mondfeld: The sinking crescent moon. The naval battle of Lepanto in 1571. Preparations, battle events, consequences. Arena, Würzburg 1973, ISBN 3-401-03675-0 .

- Harriet Rudolph: Lepanto. The order of battle and the order of memory. In: Horst Carl, Ute Planert (ed.): Military cultures of remembrance from the 14th to the 19th century. Carriers, media, interpretation competitions. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-89971-995-6 , pp. 102–127 (online) .

- Oliver Warner : Great naval battles . Ariel, Frankfurt am Main 1963.

- Elizabeth R. Wright, Sarah Spence, Andrew Lemons (Eds.): The Battle of Lepanto (= The I Tatti Renaissance Library , Volume 61). Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2014, ISBN 978-0-674-72542-3 (Collection of 21 Latin poems on the Battle of Lepanto from 1571/72 and the Austrias Carmen by Juan Latino published in 1573 with English translation and commentary ).

Movie

- The naval battle of Lepanto . D 2002, documentary , 45 min., Director: Marc Brasse, production: Spiegel TV , ZDF .

Web links

- Literature on the sea battle of Lepanto in the catalog of the German National Library

- Onur Yıldırım: The Battle of Lepanto and Its Impact on Ottoman History and Historiography.in: Papa Pio V nella società e nella politica del suo tempo. oO 2004, pp. 533-556. Visited on April 12, 2008 (PDF file; 128 kB)

- John F. Guilmartin, Jr. (US Air Force Lt. Col. ret.): Article on Tactics in Battle

- Dissertation on the Ingolstadt memorial monstrance ( TU Braunschweig , 1997)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Klaus Kreiser : The Ottoman State 1300-1922. 2nd updated edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58588-9 , p. 62.

- ^ Avner Ben-Zaken: Cross-Cultural Scientific Exchanges in the Eastern Mediterranean, 1560-1660. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD 2010, ISBN 978-0-8018-9476-3 , p. 36.

- ↑ Staale Sinding-Larsen: The Changes in the Iconography and Composition of Veronese's Allegory of the Battle of Lepanto in the Doge's Palace. In: Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 19, No. 3/4, 1956, ISSN 0959-2024 , pp. 298-302.

Coordinates: 38 ° 8 ' N , 21 ° 7' E