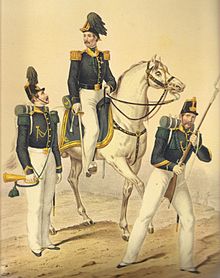

Swiss troops in Neapolitan service

The Swiss troops in the Neapolitan service comprised eleven troops from the Swiss cantons , which performed military service for the Spanish Bourbon-Sicily dynasty from 1734 to 1859 .

They served the ruling house in the 18th century to assert the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily , united in personal union, against the claims of Austria. In the 19th century they were used to support the absolutist exercise of power by the rulers and to suppress the republican efforts for freedom in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies , which has now (from 1816) been legally united . In Switzerland, this strengthened the liberal counter-movement to military service, which in 1859 enforced the abolition of Swiss troops in foreign service .

Swiss troops in foreign service was the name of the paid service of commanded, whole troop bodies abroad, regulated by the authorities of the Swiss Confederation by international treaties . These treaties contained a chapter regulating military affairs: the so-called surrender (or private surrender if one of the contracting parties was a private military contractor).

Overview of the Swiss troops in the Neapolitan service

|

before the abdication of the House of Bourbon-Sicily in 1806 |

||

| # | designation | year |

| King Charles VII. 1735–1759 | ||

| 1 | Swiss regiment Tschudi | 1734-1789 |

| 2 | Swiss regiment Jauch | 1734-1789 |

| 3 | Swiss Guard Battalion | 1734-1754 |

| 4th | Swiss regiment Nideröst / Wirz | 1748-1789 |

| 5 | Swiss Guard Regiment | 1754-1789 |

|

after the restoration of the House of Bourbon-Sicily in 1815 |

||

| # | designation | year |

| King Franz I 1825–1830 | ||

| 6th | 1st Swiss Regiment (Lucerne Regiment) |

1825-1859 |

| 7th | 2nd Swiss Regiment (Freiburg Regiment) |

1825-1859 |

| 8th | 3rd Swiss Regiment (Bündner Regiment) |

1825-1859 |

| 9 | 4th Swiss Regiment (Bern Regiment) |

1829-1859 |

| King Ferdinand II. 1830-1859 | ||

| 10 | Jäger Battalion 13 | 1850-1859 |

| King Franz II. 1859–1861 | ||

| 11 | Swiss Foreign Brigade | 1860-1861 |

The second generation of the Spanish Bourbons in Naples, 1734

With a military department of his father, King Philip V of Spain, and detachments of the Swiss regiments Bessler and Nideröst, in Spanish service on the front line, the Infante Don Carlos Sebastián de Borbón y Farnesio, who later became King Charles III of Spain, conquered . , 1734/35 the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily and proclaimed himself king. For Emperor Charles VI. the loss of that kingdom was a lesser evil than the risk of its Habsburg dynasty becoming extinct . Without any male offspring and anxious to appoint his daughter Maria Theresa as heir to the throne, he tried to win the approval of France for his pragmatic sanction and therefore consented to a secondary education of the Spanish Bourbons in Naples in the Vienna Preliminary Peace in 1735 . Don Carlos was then crowned King of Naples and Sicily in 1735 as Charles VII .

Swiss troops until the abdication of the House of Bourbon-Sicily in 1806

Charles VII immediately tried to recruit his own Swiss troops into Neapolitan services . For this purpose he turned to Josef Anton Tschudi and Karl Franz Jauch, officers of his Swiss troops in Spanish service .

Jauch and Tschudi solved the task immediately and each founded a regiment . In 1734, a battalion was spun off from the Tschudi regiment as the Swiss Guard Battalion, which later developed into the Swiss Guard Regiment . The Spanish Swiss regiment Nideröst changed in 1748, until then in Spanish pay , but since 1735 with the new owner Wirz, in Neapolitan services.

| Name, duration of use |

(1 nea ) Tschudi Swiss Regiment 1734–1789 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year, contractual partner |

1734: Private surrender of Josef Anton Tschudi from Glarus, grenadier captain in the Spanish regiment Nideröst, with the Spanish Infante Don Carlos, Duke of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, from 1735 King Charles VII of Naples and Sicily.

The surrender was quickly recognized by the Catholic authorities of the denominationally coexisting Canton of Glarus and against the position of the Diet, which referred to the lack of a state treaty with Naples, the unusual free usability of the regiment and the non-existent right of recall, and was recognized in 1754 by Charles VII and in 1776 renewed by King Ferdinand IV , his son and successor. It contained u. a. the following provisions:

This hereditary succession at the level of regiment (brother) and company (heir of the deceased) was a novelty and some of these provisions were to cause difficulties later. Further specifications: The regiment could be deployed anywhere and according to the wishes of its client (also on the sea). The Swiss recruited had to be at least 5 feet and 2 inches long and the foreign German volunteers 5 feet (about 1.50 m). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stock, formation |

1 line regiment in 4 battalions with 3 infantry (fusilier) companies each of 220 men and 1 grenadier company with 110 men including officers.

Total troop strength: 770 in the battalion and 3,080 in the regiment. The regimental staff was integrated into the 1st Battalion. Each of the 3 other battalions had their own battalion headquarters. Total troops: 3,142 people. Target stock of units:

As early as 1734 a battalion was spun off again and promoted to the Swiss Guard Battalion. When the contract was renewed in 1754, the regiment was reduced to 1,400 men in 2 battalions of 700 men each, with 3 infantry companies of 200 men and 1 grenadier company of 100 men per battalion. Before it was dissolved in 1789, the regiment numbered 1,425 men and had practically the same division and armament as the guards regiment. The flag bore the colors of the king and the colonel. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner, commander, namesake |

Recruited by Josef Anton Tschudi, Lieutenant Colonel ex Regiment Nideröst, commanded by his older brother Colonel Leonhard Ludwig Tschudi, both from Glarus.

When Leonhard Ludwig resigned from command in 1747 and transferred to the Swiss Guard Battalion as Lieutenant Colonel, Josef Anton took over the regiment again. It is not clear from the sources whether he had it run as a substitute (Ignaz Alfons Weber, Rudolf Betschart, both from Schwyz, Jakob Franz Gallati from Glarus) until 1771. In 1771 his second son Carl Ludwig Sebastian Tschudi became the regimental owner. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin squad, troop |

nominally excavated in the Catholic cantons | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Use, events |

1742 and 1744–1746 in battles in central and northern Italy against Austria and in 1768 against the papal enclave of Benevento .

Dismissed in 1789. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name, duration of use |

(2 nea ) Swiss regiment Jauch 1734–1789 |

| Year, contractual partner |

1734: Private capitulation of Karl Franz Jauch from Uri, Lieutenant Colonel in the Spanish Swiss Regiment Bessler, with the Spanish Infante Don Carlos, Duke of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, from 1735 King Charles VII of Naples and Sicily.

The surrender was hesitantly recognized by the authorities of Uri retrospectively and because of the attitude of the daily statute, which referred to the lack of a state treaty with Naples, the unusual free usability of the regiment and the non-existent right of recall, and in 1754 by Charles VII and in 1776 by King Ferdinand IV. , His son and successor, renewed. |

| Stock, formation |

1 line regiment with a division and armament like the Tschudi regiment , but with 3 battalions and the hereditary successor through the son.

Total troop strength: 770 in the battalion and 2,310 men in the regiment. Total troops: 2,362 people. When the contract was renewed in 1754, the regiment was reduced to 1,400 men in 2 battalions of 700 men each, with 3 infantry companies of 200 men and 1 grenadier company of 100 men per battalion. In 1789, before it was dissolved, the regiment numbered 1,425 men and had practically the same division and armament as the guards regiment. The flag carried the colors of the king and the colonel. |

| Owner, commander, namesake |

Dug up and commanded by Colonel Karl Franz Jauch from Uri (1739 Brigadier), handed over to his third son Karl Florian Jauch in 1743 and to his son Karl Eduard Jauch in 1781. |

| Origin squad, troop |

Nominally raised in the Catholic cantons. |

| Use, events |

1742 and 1744–1746 fights in central and northern Italy against Austria and in 1768 a campaign against the papal enclave of Benevento.

In 1753 the regiment in Messina was severely reduced by the plague, and Dismissed in 1789. |

| Name, duration of use |

(3 nea ) Swiss Guard Battalion 1734–1754 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year, contractual partner |

1734 private capitulation of Josef Anton von Tschudi from Glarus with the Spanish Infante Don Carlos, Duke of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, from 1735 King Charles VII of Naples and Sicily.

The surrender was quickly recognized by the Catholic authorities of the denominationally coexisting Canton of Glarus and against the position of the Diet, which referred to the lack of a state treaty with Naples, the unusual free usability of the regiment and the non-existent right of recall, and was recognized in 1754 by Charles VII and in 1776 renewed by King Ferdinand IV , his son and successor. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stock, formation |

In 1734 a battalion of the Tschudi regiment was promoted to the Swiss Guard Battalion. It consisted of 6 infantry (fusilier) companies of 120 men each and 1 grenadier company of 110 men including officers.

Troop strength of the Swiss Guard Battalion 1734: 830 people. In 1738 it was increased by 3 infantry companies of 120 men to 1,190 people. Target stock of units:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner, commander, namesake |

Commanded by Josef Anton von Tschudi. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin squad, troop |

As a complete battalion outsourced from the Swiss Tschudi regiment. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Use, events |

Garrison service in Naples. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name, duration of use |

(4 nea ) Swiss regiment Nideröst / Wirz 1748–1789 |

| Year, contractual partner |

1724: Surrender of King Philip V of Spain with the Catholic cantons and the Prince Abbot of St. Gallen, 1744 extended by 20 years. In 1735 the Schwyz owner and commander Karl Ignaz Nideröst was killed during the siege of Syracuse and Josef Ignaz Wirz from Obwalden was his successor. He went to Schwyz, which the regiment claimed, for confirmation and stated that:

Schwyz got entangled in quarrels with Unterwalden, represented alternately by Obwalden and Nidwalden in the Diet, which made the matter even more difficult. Schwyz was above all concerned about the cantonal ownership of the previously mostly Schwyz companies, the economic base of the local upper class, and initially did not recognize the Wirz surrender, but ultimately tolerated it. In 1748 the regiment, until then financed by the Spanish king, finally became the property of Charles VII, King of Naples and Sicily. He undertook the Spanish surrender extended in 1744, which King Ferdinand IV, his younger son and successor, renewed in 1764 and in the 1780s. |

| Stock, formation |

1 line regiment in 3 battalions with 3 infantry companies of 200 men and 1 grenadier company of 110 men.

Troop strength: 2,130 people. In 1742 the troop strength was temporarily increased to 2,840 people by relocating the 4th Battalion of the Wirz Regiment, which had been stationed in Spain, to Naples. The battalion quickly suffered enormous personnel losses and was disbanded the next year due to over-indebtedness. In 1789, before it was dissolved, the regiment numbered 1,425 men and had practically the same division and armament as the guards regiment. The flag had the colors of the king and the colonel. |

| Owner, commander, namesake |

Dismissed in 1724 with a 10-year contract (extended by 10 years in 1734) by Colonel Karl Ignaz von Nideröst from Schwyz, former Lieutenant Colonel in the Spanish Swiss Mayor Regiment, taken over in 1735 by Colonel Wolfgang Ignaz Wirz from Sarnen. |

| Origin squad, troop |

The regiment was formed in 1724 from the Catholic troops of two Protestant regiments released by Spain in 1721 for reasons of faith: the von Salis regiment (recruited in Graubünden in 1719) and the Mayor regiment (formed in 1719 from the Swiss regiments Müller and von Stockar, who were released from Venetian service). It was supplemented with recruits from the Catholic cantons and expanded from 2 to 3 battalions in 1728 and to 4 battalions in 1732. |

| Use, events |

Battalions 1, 2 and 3 of the regiment were in 1733 under the personal leadership of Karl Ignaz Nideröst with the Spanish forces of the Spanish Infante Don Carlos, from 1735 King Charles VII of Naples and Sicily, on his campaign to Naples and in the decisive battle Involved by Bitonto 1734.

In 1748 it entered the Neapolitan service. Before it was used in 1742 and 1744–1746 in the battles in central and northern Italy against Austria and afterwards in 1768 against the papal enclave of Benevento. In 1789 it was dismissed. |

| Name, duration of use |

(5 nea ) Swiss Guard Regiment 1754–1789 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year, contractual partner |

1754: Private capitulation for 20 years by Josef Anton von Tschudi from Glarus with King Charles VII of Naples and Sicily.

The surrender was recognized by Katholisch-Glarus with the proviso that the regiment would not be used against federal allies, and renewed in 1776 by King Ferdinand IV , his son and successor. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stock, formation |

The hereditary Swiss Guard Battalion in the Tschudi family was expanded in 1754 to 2 battalions of 6 infantry and 1 grenadier company of 109 men each and upgraded to the Swiss Guard regiment.

Troop strength: 1,526 people. Before the dissolution in 1789, the guard regiment was 1559 strong and comprised 2 battalions with 6 fusilier and 1 grenadier company of 109 men each. Target stock of the unit:

The soldiers were divided into 8 squads under one corporal and had to consist of Catholics and 2/3 Swiss. The uniform was red with blue facings, the trousers blue. The fusiliers wore hats, the grenadiers wore bearskin caps. The officers were armed with a sword, that of the NCOs with a flintlock shotgun and saber. The flag of the guard led four flamed fields with the Swiss cross. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner, commander, namesake |

Excavated by Josef Anton von Tschudi, taken over by his older brother Colonel Leonhard Ludwig von Tschudi in 1770 and by his son Fridolin Joseph Ignatius von Tschudi in 1779. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin squad, troop |

Nominally raised in the Catholic cantons. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Use, events |

1742 and 1744–1746 fights in central and northern Italy against Austria.

Tschudi prevented the capture of Charles VII at Velletri in 1744 by a midnight coup d'état by the Austrians and thus saved him the royal throne of Naples and Sicily. In 1768 the guard regiment was deployed against the papal enclave of Benevento and dismissed along with the three Swiss line regiments in 1789. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After initial garrison service, the troops of Naples were only involved in combat operations in the War of the Austrian Succession from 1740–1748 . It broke out with the unexpected death of the last Habsburg, Emperor Charles VI, despite the previous approval of the pragmatic sanction by the European powers, and took place largely in northern Italy.

France and Spain, with Naples in tow, allied with Prussia and Bavaria, contested Austria's daughter Maria-Theresa, supported by Sardinia and England, for the inheritance.

When the fighting broke out in 1740, King Charles VII was able to rely on the detachments of the Swiss Wirz and Bessler regiments in Spanish service in addition to his other troops, including his own three Swiss units, the latter also followed by his two battalions remaining in Spain in 1741 Italy followed suit:

| 1,526 | man | Swiss Guard Regiment |

| 2,362 | man | Swiss regiment Tschudi |

| 2,362 | man | Swiss regiment Jauch |

| 2,130 | man | Spanish Swiss Regiment Wirz (formerly Nideröst, from 1748 in Neapolitan service) |

| 1,420 | man | Spanish Swiss regiment Bessler (disbanded in 1749 when the capitulation ended) |

| 9,800 | man | Swiss troops in total (equivalent to almost a quarter of the total number of the royal Neapolitan army) |

After the initial success of the anti-Austrian alliance, the appearance of a fleet from England, allied with Austria, before Naples in 1742 slowed the ambitions of King Charles VII. He was forced to remain temporarily neutral and to withdraw the troops of Naples, with the exception of the Spanish regiments Bessler and Wirz, from northern Italy for the time being.

However, when an Austrian army division under Field Marshal Johann Georg Christian von Lobkowitz advanced south in 1744 , Charles VII opposed it with his entire army and stormed their positions near Velletri. In this decisive battle won by Naples, the Swiss troops fended off the counterattack by the Austrians, prevented the capture of King Charles VII and thus secured him the royal dignity. The capture of Naples was prevented, the Bourbons had successfully asserted themselves against Austria and Lobkowitz had to withdraw.

Until 1746 the Swiss troops were at the side of their compatriots in Spanish and French service on the battlefields of Italy with considerable losses in the assault on Pavia and Montcastel, in the defense of Valence and in the battles of Codogno and Piacenza . When they returned to Naples, their stocks had dropped to a third.

From 1747 onwards, military action shifted to the Netherlands. There was no longer any major fighting on Italian territory and in 1748 the War of the Austrian Succession was ended in the Peace of Aachen .

The problem of private capitulations, the asymmetrical distribution of power between employer and regiment owners due to the lack of anchoring in the state treaty, had already become noticeable during the war, when both parties regularly disregarded the surrender provisions. The king often acted arbitrarily, intervened in mixed cases (e.g. when a civilian vassal was involved) in the internal jurisdiction of the regiments and remained guilty, especially in the financial area. The regimental commanders, due to large personnel losses, enormous desertion rates, several epidemics, competing advertising in their homeland and Piedmontese blocking of the alpine passes when recruits were in distress, began to interpret the conditions of surrender of necessity on their own initiative: the 2/3 Swiss clause, the Catholic rule , the required minimum stocks, the required nationalities of the soldiers and other criteria were less and less taken into account.

At the end of the war, most of the units were practically insolvent and many were no longer financially able to raise or maintain the required stocks and equipment. The royal treasury was so overused that King Charles VII was forced to reduce his armed forces by a quarter. He also involved the Swiss troops, dissolved the Spanish Swiss Bessler regiment in 1749 and ordered the reduction of the line regiments Tschudi, Jauch and Wirz from three to two battalions, while reducing the target numbers of infantry companies to 200 men and grenadier companies to 100 men .

This radical Neapolitan reduction deal shook the affected power elite of the inner Swiss cantons, whose hands were tied for lack of a state treaty, and led to violent arguments with the regimental commanders. Above all, the focus was on the financial claims of the local mercenary aristocracy as company owners due to the premature termination of the pay contracts. The quarrels within Switzerland even culminated in a trial against the Uri Colonel Jauch, with a temporary ban through Schwyz, Unterwalden and Zug, before the situation calmed down again.

For the reduced regiments, this active phase was followed by a longer, quiet period, which was only interrupted twice by military operations: in 1763 by the expulsion of the Jesuits from (Spain and) Naples and a year later the campaign on the papal enclave of Benevento .

The daily routine in the garrison and the steadily decreasing quality of recruitment had an increasingly negative influence on discipline and level of training. The combat readiness of the Swiss troops began to suffer and sank to an alarming level.

Under the influence of the first events of the French Revolution in 1789, King Ferdinand IV ordered an army reform at the instigation of his wife Maria Karolina of Austria , a daughter of Empress Maria Theresa . One of the goals was lower spending on the military budget. The now tighter central financial management of the army and the tightened monthly inspection of the stocks increased the pressure on the regimental and company owners.

The general inspector of the French Swiss regiments, Brigadier General Anton von Salis-Marschlins, was charged with reorganizing the infantry. In 1789 he disbanded the four privileged Swiss regiments, which were considerably more expensive than foreign troops that were comparable in terms of performance. He reduced it to two cheaper foreign regiments under the command of foreign officers, a reorganization that lasted until the Bourbons abdicated in 1806. The demarches of the angry cantons in Naples to settle the open claims remained ineffective without an interstate treaty.

The abdication of the House of Bourbon-Sicily in 1806 and the Bonapartists 1806–1815

In 1798, local patriots in Naples proclaimed the short-lived Parthenopean Republic , and in the following year the city was occupied by French revolutionary troops in bloody battles. The king had only Sicily, where he had fled. In 1799 he returned after five months with the help of so-called Sanfedisti, a motley troupe named Esercito Cristiano della Santa Fede (Christian army of the Holy Faith), consisting of Russian volunteers, loyalist farmers and local brigands and led by Cardinal Fabrizio Ruffo , mainland back in bloody retaliation against the republican elite of Naples. In 1806 King Ferdinand IV was forced to abdicate by Napoléon Bonaparte . Napoleon installed his brother Joseph and two years later his brother-in-law Murat as kings of Naples, while Ferdinand IV resided again in Sicily. After the fall of Napoleon, he was reinstated as absolute ruler of both Sicilies with the military help of Austria in 1815.

Swiss troops after the re-establishment of the House of Bourbon-Sicily in 1815

After his reinstatement, Ferdinand IV tried to militarily emancipate himself from his Austrian supporters by recruiting Swiss troops. This recruitment did not succeed for the time being, due to outstanding claims by the regiment owners from the time before his fall, claims that were supported by the cantons.

Only his successor Franz I came back to business with the Confederates in 1825. He agreed surrenders for four new Swiss regiments, this time with the cantons. They now contained the provisions previously missing in the private capitulations and were ratified by the Diet.

These surrenders included the following provisions:

1. The mission :

The regiments were not allowed to be deployed on warships, not in non-European countries and not in the Neapolitan corps association, and they were not allowed to be divided;

2. The appointments :

Officers were elected by the king, the following additional provisions applied: higher officers from the level of major, the king was free, with the exception of the officers of the Uri regiment (1st regiment), who had to be cantons. He appointed grand judges, auxiliary majors, field chaplains, medical officers and standard-bearers at the suggestion of the colonel, the administrative officers at the suggestion of the regimental board of directors (the canton's supervisory body on surrender) and all other officers at the suggestion of the cantons concerned;

NCOs were elected either by the colonel (NCOs of the small staff on the proposal of the major) or by the major (NCOs of the companies on the proposal of the captain);

Musicians and schoolmasters were elected by the regimental board of directors;

3. Regulations regarding flags, weapons and uniform:

The regimental flags bore the Swiss cross in the red field and the arms of the capitulating cantons on one side and the arms of the King of the Two Sicilies on the other;

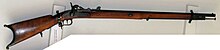

The armament of the crew consisted of a rifle and infantry saber as a side gun. In the 1850s, at the request of Lieutenant Colonel Felix von Schumacher, a minié rifle made in Belgium was introduced into the Swiss regiments, as in the entire Neapolitan army ;

The parade uniform was scarlet with light blue, straw yellow, dark blue or black lapels depending on the regiment, white (summer) or blue (winter) trousers and shakos.

The gunmen's uniform was blue above and below.

The work uniform was gray, consisting of trousers and a sleeve vest or kaput;

4. The jurisdiction :

According to the military law for Swiss regiments in French service, drawn up by General Nicolas de Gady from Freiburg i / Ü, the following penal code was approved by the Diet in 1817:

The court martial ruled with the grand judge and two officers called in by him, as well as a Fourier as clerk, the colonel and some staff officers as prosecutor, all sworn, in the open air and in the middle of the regiment led by the lieutenant colonel.

The officers' tribunal ruled with six officers of the same rank per rank and presided over by the senior Swiss officer. The sentence could be converted into a prison sentence.

The verdict was examined by the prosecutors in a closed session, either confirmed, tempered or dealt with with a pardon.

The execution was carried out immediately after the confirmation of the judgment. Depending on the severity of the offense, it consisted of: execution, lifelong confinement in an island fortress (Ergastolo), galley penalty (Galera), forced labor in a penal institution (Presidio) or running the gauntlet with expulsion from the regiment if the mustache and hair on the left had been previously shaved Side of the head.

The disciplinary punishments imposed on subordinates by officers and NCOs were confirmed by the colonel and their duration and form were determined.

The colonel (in his own competence) could order prison sentences of up to 3 months, which he could extend for over-indebted officers or tighten them for the crew by means of chains or water and bread regimes. He could hire non-commissioned officers on duty or, with the help of a disciplinary board (consisting of the chief judge and two staff officers and two company captains) , punish them with corporal punishment , demotion and expulsion from the regiment.

The king had no right to intervene in these processes;

5. The practice of religion :

Protestants, such as B. the 4th (Bern) Regiment, freedom of worship was granted. The Protestant service, however, had to take place inside the barracks or in the chapel of the Prussian embassy. Protestants also had separate burial places;

6. The right of recall :

Was granted to the cantons in the event of their own case of war.

The levies of Swiss regiments 1 to 3 based on this surrender began immediately, Bern followed a little later when the dismissal of the Swiss troops in Holland became apparent.

| Name, duration of use |

(6 nea ) 1st Swiss Regiment Lucerne Regiment, nickname: "les catze-strèque" (the cat stretcher) 1825-1859 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year, contractual partner |

1825 Capitulation of Franz I, King of the Two Sicilies, with the cantons of Lucerne, Uri, Unterwalden and Appenzell Innerrhoden. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stock, formation |

1 line regiment of 1,452 men, later 1,600 men, in 2 battalions, the battalion with 4 (cantonal) fusilier companies and 2 elite companies ( grenadiers and hunters or voltigeurs ).

Target stock of the unit:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner, commander, namesake |

1825 Colonel Ludwig von Sonnenberg from Lucerne, 1831 Colonel Ludwig Schindler from Lucerne, 1845 Lieutenant Colonel Josef Leonz Siegrist from Ettiswil, 1849 Colonel Martin Mohr from Lucerne, 1856 Colonel Alfons Bessler from Uri. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin squad, troop |

Mainly excavated in Lucerne (7 companies), Uri (1), Nidwalden (2), Obwalden (1) and Appenzell Innerrhoden (1). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Use, events |

The first two decades were marked by garrison service on the mainland and in Sicily.

He was affected by a cholera epidemic in the 1830s and 1850s, which also claimed victims among the troops. In the revolutionary years of 1848/49, the troops were used to suppress the uprisings of the people on the Neapolitan mainland who were demanding a democratic constitution. In 1849 the hunter companies of the 1st regiment, together with those of the 2nd regiment, were involved in a special battalion under Major Schaub in the French expeditionary corps of General Nicolas Charles Victor Oudinot in the suppression of the Roman Republic and the restoration of rule of the Roman Catholic Church . In 1859 the regiment was disbanded. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name, duration of use |

(7 nea ) 2nd Swiss Regiment Freiburg Regiment, nickname: "les dzozés" (from Joseph) 1825–1859 |

| Year, contractual partner |

1825 Surrender of Francis I, King of the Two Sicilies, with the cantons of Friborg and Solothurn. |

| Stock, formation |

Like the 1st Swiss Regiment. |

| Owner, commander, namesake |

1825 Colonel Karl Emanuel von der Weid from Freiburg, 1832 Colonel Heinrich von Sury von Solothurn, 1839 Colonel François Joseph Nicolas de Buman von Freiburg, 1847 Colonel Joseph Viktor Franz Ludwig Brunner von Solothurn, 1849 Colonel Tobias von Müller von Freiburg, 1850 Colonel Karl von Sury von Solothurn, 1852 Colonel Wolfgang Adolf von Rascher von Chur. |

| Origin squad, troop |

Mainly excavated in Freiburg (6 companies) and Solothurn (6). |

| Use, events |

Like the 1st Swiss Regiment. |

| Name, duration of use |

(8 nea ) 3rd Swiss Regiment Bündner Regiment, nickname: "les goîtreux" (the goiters) 1825-1859 |

| Year, contractual partner |

1825: Capitulation of Franz I, King of the Two Sicilies , with the cantons of Valais (1 battalion), Schwyz (1827 for 1/2 battalion, i.e. 3 companies) and Graubünden (1828 for 1/2 battalion, i.e. 3 companies). |

| Stock, formation |

Like the 1st Swiss Regiment. |

| Owner, commander, namesake |

1825 Colonel Hieronymus von Salis-Soglio from Chur, 1829 Colonel Eugen von Stockalper de la Tour von Brig, 1840 Colonel Pierre-Marie Dufour from Vionnaz-Monthey, 1848 Colonel Augustin von Riedmatten. |

| Origin squad, troop |

Mainly excavated in Valais (6 companies), Schwyz (3) and Graubünden (3). |

| Use, events |

The first two decades were marked by service in changing garrisons on the mainland and in Sicily. He was burdened in the 1830s and 1850s by working against the cholera epidemics, which also claimed victims among the troops. In the revolutionary years of 1848/49, the troops were used to suppress the uprisings of the people on the Neapolitan mainland and in Sicily, who demanded a democratic constitution. In 1849 the 3rd regiment in General Nicolas Charles Victor Oudinot's French expeditionary corps was involved in the suppression of the Roman Republic and the restoration of rule of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1859 it was the starting point of the revolt, which was suppressed by the Jäger Battalion 13, and which led to the dissolution of the Swiss troops in the Neapolitan service in the same year. In 1859 the regiment was disbanded. |

| Name, duration of use |

(9 nea ) 4th Swiss Regiment Bern Regiment, nickname: "les moutse" (the Mutzen, Swiss German: Mutz = bear) 1829–1859 |

| Year, contractual partner |

1828 Surrender of Francis I, King of the Two Sicilies, with the Canton of Bern. |

| Stock, formation |

Like the 1st Swiss Regiment. |

| Owner, commander, namesake |

1828 Colonel Friedrich Albert von Wyttenbach from Bern, 1834 Colonel Henri-Victor-Louis de Gingins, 1848 Colonel Ludwig Bernhard Karl von Muralt from Bern, 1849 Colonel Johann Rudolf Bucher from Bern, 1850 nominally Colonel Alexander Karl von Steiger (-Wichtrach) from Bern , led by Lieutenant Colonel (Colonel 1854) Johann Karl Albert von Wyttenbach von Bern, son of the first commandant, 1859 Colonel Karl Viktor Weiss von Biel. |

| Origin squad, troop |

Mainly Bern (12 companies), excavated from the remnants of the Swiss regiments Jung-Jenner, Ziegler, spokesman for Bernegg and Auf der Maur, who had abdicated in Holland in the same year (1814/15). |

| Use, events |

The first two decades were marked by garrison service on the mainland and in Sicily. The regiment was stationed in Capua, a garrison spared the cholera, in the 1830s. In the 1850s, on the other hand, in action against the renewed cholera epidemic, the regiment suffered losses despite rigorous hygiene measures. In the revolutionary years of 1848/49, the troops were used to suppress the uprisings of the people on the Neapolitan mainland and in Sicily, who demanded a democratic constitution. In 1849, the 4th Regiment in General Nicolas Charles Victor Oudinot's French Expeditionary Corps was involved in the suppression of the Roman Republic and the restoration of rule of the Roman Catholic Church. In 1859 it was swept away by the revolt of the 3rd Swiss Regiment and when it was suppressed by the Jäger Battalion, 13 people died. This rebellion also tipped the scales for the dissolution of Swiss troops in the Neapolitan service in the same year. In 1859 the regiment was disbanded. |

After the initial benevolent support by King Franz I, once a pupil in Hofwil in Bern and supposedly able to speak Swiss German, after his death in 1830 under his son and successor Ferdinand II, despite the official surrenders, the former arbitrariness returned. However, the economic privileges in the kingdom and the lack of alternatives made the cantons regularly ignore the royal arbitrariness. The mood in Naples itself also turned more and more against the Swiss troops, who acted on behalf of the despotic regime in 1830 against the sympathizers of the July Revolution and several times against participants in anti-monarchist conspiracies. The rest of the Neapolitan troops were also offended by their privileges and above-average financial compensation.

Finally, in 1848 the defeat of the Neapolitan Revolution and in 1849 the Roman Republic in the name and for the preservation of the absolutist monarchy of Naples by the Swiss troops aroused great outrage among the liberal, progressive parties of young Switzerland and brought about a political breakthrough. In 1849, at the request of the Federal Council, the federal councils decided to lift the capitulations of Swiss troops in foreign services and to ban all advertising in Switzerland. However, some cantons objected, viewed the decision as an interference with cantonal sovereignty and referred to the question of compensation for crew and officers in the event of a recall before the end of the surrender. The federal decree was not implemented in order to await the end of the surrenders in 1855.

King Ferdinand II was by no means willing to dismiss his Swiss troops. In 1850 he even expanded the four regiments by one battalion each and also had a Swiss hunter battalion raised, albeit with a private surrender with some officers that Switzerland had not ratified.

The Swiss authorities then stopped advertising for the Neapolitan service on their territory and the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont closed the collection depot in Genoa for the recruiting of these troops. Naples reacted by opening the advertising outlets Besançon, Bregenz, Feldkirch, Bludenz, Como and Lecco outside of Swiss territory on Austrian and French territory. The rush of young, adventurous people from all over Switzerland was nevertheless large, to the displeasure of the Federal Council. There were also increasingly dubious elements (drinkers, unpopular people deported by the authorities and even delinquents) among them, which was detrimental to the level of the troops and a main reason for the occasional atrocities and looting. Some commanders even had to answer to a committee of inquiry in Switzerland.

Technical data:

• Weapon : muzzle loader, length 1260 mm, weight 4.5 kg;

• Bayonet : length 510 mm, triangular blade, fastened with a sliding spring;

• Barrel : caliber 10.5 mm, length 813 mm, 8 trains, right-hand twist;

• Sight : quadrant sight , division 200 to 1000 steps, sight line 725 mm;

• Trigger : set trigger , percussion lock;

• Ignition : primer cap;

• Ammunition : paper cartridge, charge 4 g black powder;

• Bullet : Soft lead, compression and deformation pointed bullet , in a lining made of cotton cloth soaked in fat, weight 17 g, initial speed 440 m / sec

| Name, duration of use |

(10 nea ) Jägerbataillon 13 1850-1859 |

| Year, contractual partner |

1850 Private capitulation of Ferdinand II, King of the Two Sicilies, with Lieutenant Colonel Franz Emanuel Lombach from Bern and his officers, not recognized by the Swiss authorities. |

| Stock, formation |

1 battalion with 6 fusiliers and 2 elite companies (grenadiers and hunters) of 900 men in dark green uniform.

At the request of Lieutenant Colonel Felix Schumacher, it was equipped with the federal sniper butcher, obtained from Escher Wyss in Zurich. |

| Owner, commander, namesake |

Excavated in 1850 by Lieutenant Colonel Franz Emanuel Lombach from Bern and, after his early death in 1850, managed by Lieutenant Colonel Johann Lucas von Mechel from Basel. |

| Origin squad, troop |

From all over Switzerland and partly from abroad. |

| Use, events |

His use in the sharp shot of 1859 in the suppression of the revolt of the 3rd and 4th Swiss Regiments - an exchange of fire between Swiss troops with a Swiss weapon! - ended with 49 deaths and accelerated the disintegration of the Swiss troops in Naples.

The 13th Jäger Battalion was now part of the king's core force before the other 12 Swiss battalions. In 1859 the battalion was disbanded and the majority was taken over by the 3rd Foreign Battalion. |

King Ferdinand II got ahead of the Swiss authorities and in 1854, one year before the end of the surrenders, extended the service of his Swiss troops by a further 30 years by concluding private surrenders with the commanders, contracts that were not approved by the Swiss authorities. This affront heated the mood of the opposition in Switzerland against the Swiss troops in foreign service.

The end of Swiss troops in foreign service in 1859

When the second Italian War of Independence broke out in 1859 , which finally opened the way to the unification of Italy, the Swiss Federal Council was forced to react. Above all England and France, the protagonists of the liberal revolution, pushed for the withdrawal of the cantonal Neapolitan surrender and the Swiss troops, with reference to the neutrality of Switzerland decreed by the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The Federal Council then ordered the removal of all national and cantonal emblems on the flags of Swiss troops in Neapolitan service, which led to a brutally suppressed revolt by soldiers of the 3rd and 4th Swiss Regiments. This in turn prompted the Federal Council to apply for a special law in both parliaments that made the service of Swiss in foreign troops, which could not be considered national troops of the state concerned, as well as the recruitment of such troops under severe penalties. The law was passed and a month later the young King Francis II ordered the dissolution of all Swiss troops in the Neapolitan service.

Of the approximately 12,000 troops released in 1859, around half returned to Switzerland, 800 men joined the papal army , others were recruited by the French Foreign Legion or the Dutch troops on Java. 1,800 men, however, stayed in Naples and formed a new body of troops as the Swiss foreign brigade, without the involvement of the federal authorities.

| Name, duration of use |

(11 nea ) Swiss Foreign Brigade 1860–1861 |

| Year, contractual partner |

1860 Private capitulation of Francis II , King of the Two Sicilies, with Colonel Johann Lucas von Mechel, against the will of the Swiss federal authorities. |

| Stock, formation |

A combat brigade consisting of the three Swiss Foreign Battalions 1, 2 and 3, the Swiss Veterans Battalion and the Artillery Foreign Battery 15.

The 1st Swiss Foreign Battalion was formed from the remnants of the 1st Regiment, the 2nd Swiss Foreign Battalion from volunteers from the other 3 regiments and the 3rd Swiss Foreign Battalion from the almost complete Jäger Battalion 13 and comprised a total of 1,800 men. The Swiss veteran battalion with 4 companies was already assembled in 1859 from troop members of the Swiss line regiments 1 to 4 who were released there. The foreign artillery battery 15 , with 5 officers, 174 NCOs, artillerymen and train soldiers, 136 horses and 6 six-pounders, arose from the artillery sections of the four Swiss line regiments. |

| Owner, commander, namesake |

The combat brigade was commanded by Colonel Johann Lucas von Mechel from Basel, with the battalion commanders: 1st Swiss Foreign Battalion : 1860 Lieutenant Colonel Franz Xaver Göldlin from Lucerne; 2nd Swiss Foreign Battalion : 1860 Colonel Alois Migy († 1860) from Pruntrut, followed in 1860 by Major Franz Anton von Werra from Leuk; 3rd Swiss Foreign Battalion : 1860 first in personal union Colonel Johann Lucas von Mechel, after his promotion (1860 Brigadier) in the same year replaced by Major Eugen Gächter († 1861) from St. Gallen and in 1861 by Major Johann Heinrich Wieland from Basel; Swiss Veteran Battalion : 1860 Lieutenant Colonel Eugen Emanuel Tschiffeli von Bern; Artillery foreign battery 15 : In 1860 first captain Heinrich Fevot († 1860) from Lausanne, followed in 1860 by captain Robert von Sury from Solothurn. |

| Origin squad, troop |

Volunteers from the disbanded Swiss troops in the Neapolitan service as a tribe, supplemented by recruits recruited in Austria-Hungary.

Many officers were sons from Neapolitan mixed marriages of Swiss. In contrast to the officers' corps , the majority of the team was already non-Swiss |

| Use, events |

General Felix von Schumacher

Finally, in this last refuge of the royal family, under General Felix von Schumacher from Lucerne and his adjutant Max Alphons Pfyffer von Altishofen, Generals Augustin von Riedmatten (section commander sea side of the fortress) and Josef Sigrist (land side), the siege by the for months Piedmontese troops stood before it evacuated the totally destroyed fortress. Schumacher accompanied the royal family into exile in Rome in 1861 after the abdication of Franz II. The Bourbon army was disbanded, and many troops joined the army of the Kingdom of Italy. The surviving Swiss officers were interned in the Papal States for some time before they were released home. Schumacher continued his career in Lucerne as a promoter of steam shipping and the shooting industry. Pfyffer became the Swiss Chief of Staff and the initiator of the Gotthard fortress . |

With the dissolution of the four Swiss regiments in Naples in 1859, the chapter of Swiss troops in foreign service , with the exception of the papal Swiss guard, was finally over.

The special law against the service of Swiss troops abroad, which came into force in 1859, however, proved to be ineffective against service in the foreign legions. Since these, commanded by officers of the state concerned, were regarded as national troops, they were not covered by this law. It was not until 1927 that Article 94 of the Military Criminal Law made individual military service by Swiss citizens abroad generally punishable without the approval of the Federal Council.

literature

- Beat Emmanuel May (by Romainmôtier): Histoire Militaire de la Suisse et celle des Suisses dans les differents services de l'Europe. Tome VII, JP Heubach et Comp., Lausanne 1788, OCLC 832583553 .

- Karl Müller von Friedberg : Chronological representation of the federal surrender of troops to foreign powers. Huber and Compagnie, St. Gallen 1793, OCLC 716940663 .

- Wolfgang Friedrich von Mülinen : History of the Swiss mercenaries up to the establishment of the first standing guard (1497). Dissertation to obtain a doctorate, University of Bern, Verlag von Huber & Comp, Bern 1887, OCLC 610789020 .

- Friedrich Moritz von Wattenwyl : The Swiss in Foreign Service A look back at the military capitulations. Separately printed from the Berner Tagblatt , Bern 1930, OCLC 72379925 .

- Paul de Vallière, Henry Guisan , Ulrich Wille : Loyalty and honor, history of the Swiss in foreign service (translated by Walter Sandoz). Les éditions d'art ancien, Lausanne 1940, OCLC 610616869 .

- Robert-Peter Eyer: The Swiss regiments in Naples in the 18th century (1734-1) 789 , Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften Peter Lang AG, Bern 2008, OCLC 758759765 .

- Alfred Tobler : Experiences of an Appenzeller in Neapolitan service 1854 - 1859 , Fehr'sche Buchhandlung (formerly Huber & Co.), St. Gallen 1901. Transcription of the original by Andres Stehli, Head of Museum Heiden, Antiquarian Association, Heiden January 3, 2016 .

See also

Web links

- Military Criminal Law 1927 (PDF)

- Ergastolo (Italian)

- The Battle of Bitonto 1734 (Italian)

- The Battle of Velletri 1744 (Italian)

- Federal sniper supporter 1851

- March of the 3rd Swiss Regiment Youtube video with picture sequence

Individual evidence

- ^ Feller-Vest, Veronika: Tschudi, Josef Anton. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Stadler, Hans: Jauch, Karl Franz. In: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz .

- ^ A b c d e f Robert-Peter Eyer: The Swiss regiments in Naples in the 18th century (1734–1789 ), Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften Peter Lang AG, Bern 2008.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Heinrich Türler, Viktor Attinger, Marcel Godet: Historisch-Biographisches Lexikon der Schweiz , fourth volume, Neuchâtel 1927.

- ↑ a b c d Oskar Erismann: The Swiss in Neapolitan service , sheets for Bernese history, art and antiquity, Volume 14, Issue 1, 1918.

- ↑ Feller-Vest, Veronika: Tschudi, Leonhard Ludwig. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Feller-Vest, Veronika: Tschudi, Carl Ludwig Sebastian. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Kälin, Urs: Jauch, Karl Florian. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Kälin, Urs: Jauch, Karl Eduard. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Auf der Maur, Franz: Nideröst, Karl Ignaz. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Garovi, Angelo: Wirz, Wolfgang Ignaz. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Feller-Vest, Veronika: Tschudi, Fridolin Joseph Ignatius von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Färber, Silvio: Salis, Anton von (Marschlins). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Müller-Grieshaber, Peter: Schumacher, Felix von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Rial, Sébastien: Gady, Nicolas de. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ a b c d e f Moritz von Wattenwil, The Swiss in foreign military service , separate print from the “Berner Tagblatt”, Bern 1930.

- ^ A b c d e f Paul de Vallière: Loyalty and honor, history of the Swiss in foreign service . German edition by Lieutenant Colonel H. Habicht. Les editions d'art ancien, Lausanne 1940.

- ^ A b c d Fritz Fankhauser: From the letters of a "Napolitaner" from Oberaargau , Burgdorfer Jahrbuch 1958, Kommissionsverlag Langlois & Cie 1958.

- ↑ a b c d e f Albert Maag: History of the Swiss Troops in Neopolitan Services 1825–1861 , Commission publisher von Schulthess 1909.

- ^ Quadri, Peter: Sonnenberg, Ludwig von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Lischer, Markus: Siegrist, Josef Leonz. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Meyer, Erich: Sury, Karl von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Simonett, Jürg: Salis, Hieronymus von (Soglio). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Putallaz, Pierre-Alain: Riedmatten, Augustin von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Braun, Hans: Wyttenbach, Friedrich Albert von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Rial, Sébastien: Gingins, Henri-Victor-Louis de (La Sarraz). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Obituary: Felix von Schumacher, at the time a general in the service of the King of the Two Sicilies , Allgemeine Schweizerische Militärzeitung, No. 52, Basel 1894.

- ^ A b Müller-Grieshaber, Peter: Mechel, Johann Lucas von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Alfred Tobler : Experiences of an Appenzeller in Neapolitan service 1854-1859 , Fehr'sche Buchhandlung (formerly Huber & Co.), St. Gallen 1901. Transcription of the original by Andres Stehli, Heiden 2016, pages 31ff.

- ↑ Müller-Grieshaber, Peter: Schumacher, Felix von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Lischer, Markus: Pfyffer, Max Alphonsus (Altishofen). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Karin Marti-Weissenbach: May, Beat Emmanuel (from Romainmôtier). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ^ Christian Müller (2): Mülinen, Wolfgang Friedrich von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Hans Braun: Wattenwyl, Friedrich Moritz von. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Olivier Meuwly: Valliere, Paul de. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .