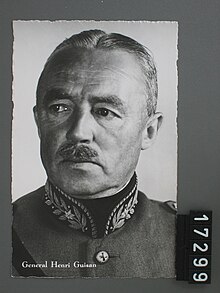

Henri Guisan

Henri Guisan (born October 21, 1874 in Mézières , † April 7, 1960 in Pully ) was general and thus commander in chief of the Swiss Army during the Second World War .

biography

Origin, youth and studies

Henri Guisan's father Charles-Ernest Guisan was a country doctor . His mother, Louise-Jeanne Bérangier, who had lung disease, died ten months after he was born. At the age of ten Guisan went to the Progymnasium in Lausanne , where he was a member of the Corps des Cadets affiliated with the school . He later became a member of the Swiss Zofinger Association . To improve his German, he was sent to Germany for six months . After his return he graduated from high school and began studying medicine. Since medicine did not suit him, he switched from science and law to an agricultural degree, which he then finished in Lyon .

Military career

On December 13, 1893, Henri Guisan was assigned to the cavalry , but was able to complete the summer artillery recruit school in Bière as a field artilleryman. As a result, he made a steep career in the military. By the First World War he reached the degree of major . During the war he was several times on the German Eastern Front to learn war tactics.

He held the following ranks in the Swiss Army :

- from 1894: Lieutenant

- from 1904: captain

- from 1908: Captain in the General Staff

- from 1911: major ; Transfer from field artillery to infantry

- from 1916: Lieutenant Colonel in the General Staff

- from 1919: Chief of Staff of the 2nd Division , Commander of the 9th Infantry Regiment

- from 1921: Colonel Brigadier

- from 1927: Colonel division

- from 1932: Colonel Corps Commander

Colonel Brigadier, Colonel Division and Corps Commander are historic ranks. The designation "Colonel" for senior staff officers was dropped in 1977.

Family, IOC

In 1897 he married Mary Doelker and settled as a farmer in Chesalles-sur-Oron . The couple had children Henry and Myriam. In 1902 he took over the estate of his father-in-law Verte Rive in Pully near Lausanne.

In the 1930s he was also active on the International Olympic Committee .

general

When the situation in Europe came to a head in the summer of 1939, Corps Commander Guisan was elected General of the Swiss Army by the United Federal Assembly on August 30, 1939 - a military rank that does not exist in the Swiss Army in peacetime . Because of his undisputed abilities and because the French-speaking part of the country was only represented in the government by one Federal Council at the time, Guisan was immediately elected with 204 of 229 valid votes. Guisan was strongly supported by his friend Rudolf Minger , who was then head of the Federal Military Department (Defense Minister).

On the basis of Guisan's operational order No. 2 of October 4, 1939, most of the Swiss army moved to the Limmat position in order to be able to stop an attack from the north and a bypassing of the Maginot line through Switzerland. This army position was directed unilaterally against Germany. In terms of neutrality law, Switzerland should have occupied the western border against France in the same way, but the troops were missing for this.

With Plan H , a secret agreement between the French and Swiss armies to occupy the prepared defensive position on the Gempen plateau by French troops, the aim was to prevent the German armed forces from being able to bypass the French Maginot Line through Switzerland. The agreement was correct in terms of neutrality law because there was no automatic mechanism and the French troops would only have been put on the march after a German attack and a request from the Federal Council for help.

During the war , Guisan always knew how to strengthen the military will of the Swiss soldiers and the population. In contrast to the custom at the time, General Guisan sought contact with ordinary soldiers and the commanders of the lower ranks on numerous visits to the troops. He ordered all commanders at level military units ( battalion and division) on 25 July 1940, his report on the Rütli ( Rütli Rapport ), where he Réduit announced strategy. On August 1, he then gave a radio address broadcast nationwide in the languages of Switzerland, which renewed the will of the population to defend: "Could we resist?" . A week after the 25th, a large-scale inspection visit followed at today's Guisanplatz near Arosa . In addition, he started the reconnaissance organization Army and House .

Guisan was adopted as general on August 20, 1945. In 1947 he submitted his 270-page report on the time of active service to the Federal Assembly.

Henri Guisan died on April 7, 1960. He was buried in Pully. In addition to many streets, squares, memorial stones and equestrian monuments, the portrait photographs hanging on the wall in older taverns still remind of General Guisan. The funeral was a real state funeral , which is not provided for in the Swiss Confederation; The church bells rang across the country on April 12th at 1:30 p.m. and around 300,000 people paid their last respects to Guisan in addition to the entire Federal Council , many former Federal Councilors and other honorable members.

Guisan was a citizen of Avenches and Mézières . The barracks on the Waffenplatz in Bern and one in Bure in the canton of Jura were named after him . The asteroid (1960) Guisan is also named after him .

Controversy over the historical classification

The generation of contemporary witnesses ( Working Group Lived History ) and the traditional historians ( Walther Hofer , Herbert Reginbogin , Jürg Stüssi-Lauterburg ) agree that Guisan and the Réduit strategy are primarily responsible for keeping Hitler from occupying Switzerland. The small orientation booklet Switzerland of the High Command of the German Army of September 1, 1942 confirms from the opponent's point of view: “ The determination of the government and the people to defend Swiss neutrality against any aggressor has so far been beyond doubt. »

Under the influence of the generation of 68 , the importance of Guisan and the myth that surrounds him as a person were questioned by historians such as Jakob Tanner and Hans Ulrich Jost , and the importance of the Réduit was relativized. Around this time and later, it played a role that a great number of important documents from the war period only became accessible to research at that time, after a 35-year blocking period. And the first Guisan biographer to use Federal Archives files, Willi Gautschi , put the Rütli report into perspective by referring to the general's suggestion to the Federal Council to send a diplomatic mediation mission to Berlin - which the state government refused.

In the Bergier report , the military constraints, the réduit and the general were not a research topic. Research was conducted into economic cooperation and the question of whether Hitler could not have waged a war without the Swiss economy. According to Markus Somm's interpretation, the final report states that the contribution of the Swiss economy to the German war economy was negligible.

The author of the current Guisan biography, Markus Somm, assumes that Guisan should have been aware of what was done to Jews by Germans in the east from spring 1942 onwards. However, the Federal Council was responsible for refugee policy, while Guisan was responsible for the security situation. For Guisan, consideration for the security of the country was also the top priority in solving the refugee question. After the fall of France, around 50,000 defeated French, Poles and North Africans had to be interned, fed and militarily guarded in addition to the civilian refugees. Nevertheless, Guisan made a differentiated judgment at the time: “ It is clear that the question of children must be judged differently than that of adult civilian refugees. »

With regard to Guisan's political stance, Markus Somm said the following in an interview in 2010: “ There were forces in the bourgeoisie who were of the opinion that the revolutionary-thinking political left had to be stopped, and they propagated a so-called corporate state . Parliament would have played a less influential role, and one dreamed of a powerful Federal President. Guisan also succumbed to this zeitgeist. »

Federal Councilor Hermann Obrecht declared on March 15, 1939: « […] We Swiss will not go on pilgrimages abroad. “This saying says that no Swiss politician or military will travel to Nazi Germany and Switzerland will never be ready to collaborate . Even after Guisan's contacts with the French and German military became known, the Swiss people had no doubts about Guisan's will to defend Swiss independence by all means. Guisan's Réduit gave the Swiss the feeling that they had survived the war happily on their own.

“Gratitude is not a long-lasting feeling. And if public opinion still recognizes your contribution to the preservation of the country's freedom today, this recognition may soon fade. You will only be able to count on active service as a moral capital to a modest extent - as beautiful and precious as your and our memories of this time are. Strictly speaking, this capital only counts for you and your comrades. "

Publications

- Report to the Federal Assembly on active service 1939–1945. Lausanne / Bern 1946.

- Conversations. Twelve programs on Radio Lausanne, directed by Major Raymond Gafner. With a foreword by former Federal Councilor Rudolf Minger . Scherz, Bern 1953.

- The speech on August 1, 1940: Could we resist? filmed by Jean Bulot.

See also

literature

- Willi Gautschi : General Henri Guisan: the Swiss army command in World War II. Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich 1989.

- Willi Gautschi: Guisan and Wille in the dangerous summer of 1940. Gautschi, Baden 1988. Reprint from: Neue Zürcher Zeitung from Saturday / Sunday, 20./21. August 1988, no.193.

- Markus Somm: General Guisan: Swiss-style resistance. On the 50th anniversary of death. Verlag Stämpfli, Bern 2010, ISBN 978-3-7272-1346-5 .

- Jon Kimche: General Guisan's Two Front War. Switzerland between 1939 and 1949. Ullstein, Frankfurt / Main, 1962 (English original title: Spying for Peace, Weidenfels and Nicolson, London, 1961)

- Hermann Berger: How the General Guisan March came about . In: Oltner Neujahrsblätter , Vol. 19, 1961, pp. 80–83.

Web links

- Hervé de Weck : Guisan, Henri. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Publications by and about Henri Guisan in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Henri Guisan in the database Dodis the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- Henri Guisan in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives

- Center Général Guisan

- Arte from July 5, 2018: Big speeches: Henri Guisan - Could we resist? youtube.com

- Information and sound recordings in the Swiss National Sound Archives

Individual evidence

- ^ Hervé de Weck: Henri Guisan. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ Federal Assembly (Switzerland): Speech by the Federal President and extraordinary meeting of the Federal Councils and election of the general. Swiss National Sound Archives , August 28, 1939, accessed on October 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Jon Kimche: General Guisan's Two Front War. Switzerland between 1939 and 1949 . Ullstein, Frankfurt / Main 1962, p. 41 f .

- ↑ Jürg Stüssi-Lauterburg: Free rock in brown surf. Speech on the 70th anniversary of the mobilization of war, Jegenstorf, September 2, 2009.

- ^ Arte : Great speeches: Henri Guisan. Video online, 12 min

- ↑ Jürg Stüssi-Lauterburg , Dramatic Summer 1942, speech at Museum Night 2010 in the library on Guisanplatz, Bern.

- ↑ dasmagazin.ch ( Memento of 23 November 2010 at the Internet Archive ) and Markus Somm

- ^ Regulations for the Federal Archives, edition of August 1, 1966

- ↑ Markus Somm: The friendly commander.

- ↑ Somm: Guisan. P. 211 ff.

- ↑ Swiss Academic and Student Newspaper. June 2010.

- ↑ Guisan in July 1940: “ As long as there are millions of armed men in Europe and as long as significant forces can attack us at any time, the army must stand at its post. »(Somm: p. 12 ff.)

- ↑ Last army report. KP in Jegenstorf 1945.

- ↑ Could we resist? Directed by Jean Bulot, Switzerland, 2018, 14 min.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Guisan, Henri |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | General in the Swiss Army during World War II |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 21, 1874 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mezieres VD |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 7, 1960 |

| Place of death | Pully |