The Slav Epic

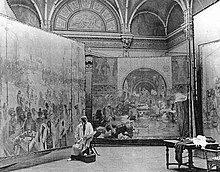

The Slavic Epic , in its original title Slovanská Epopej , is a cycle of paintings and the main work of the Czech painter Alfons Mucha . It shows the history of the Slavic peoples and consists of 20 large-format tempera paintings on canvas that were created between 1911 and 1928.

Emergence

Mucha was best known for sensual female allegories and Art Nouveau poster art . His decorative work as a "utility artist" was lucrative, but it did not fill it. In his later phase he broke away from commercial creativity in order to devote himself to the realization of an ongoing concern: “At the height of his success, the longing germinated in Mucha to break with the previous service of his art and to deal with the incessant flow of orders [... ] to stop ”. The idea for the Slav Epic came to Mucha in 1899 while designing the pavilion for Bosnia-Herzegovina for the Paris World Exhibition in 1900 . Afterwards he must have traveled a lot through the Slavic countries for his research. He looked for his sources of inspiration in specialist literature and debates with historians, architects and folklorists. The cycle could be realized through the financial coverage of Mucha's friend, Slavophile millionaire Richard Crane. The American industrialist paid for all the necessary resources, not just the painting utensils, but also the rent for the workplace, which was located in the Zbiroh Castle in western Bohemia due to the huge canvases . The Slav Epic was non-commercial; after its completion and presentation in 1928, it was given to the city of Prague free of charge. Mucha himself said that "I considered the work to be my sacred duty, and therefore I have no merit for it, and it should not be paid work either". However, he made the condition that a separate pavilion for the Slavic epic should be built in Prague.

Motifs

The Slav Epic is primarily about religious, military and cultural issues. Allegories are common. The paintings are not classically structured, but rather like a collage . The figures are based on photographic templates. They show a clear focus on Czech history and its Protestant line. The artist dedicated ten pictures to his own people, half of the Slavic epic. The others show three general Slavic, two Russian and one Bulgarian, one Serbian, one Croatian and one Polish theme. However, Czech characters or references are often hidden in the motifs of other countries as well. The 20th part and conclusion is the comprehensive painting “ Apotheosis ” (Glorification). This work was also created as the last of the epic.

| No. | title | year | image | Context / image description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Slavs in their original home | 1912 |

|

The picture shows Adam and Eve the Slavs as innocent frightened farmers. In the background, hordes plunder a Slavic city. The earthly scene is contrasted with a pagan priest. At his side you can see a young man who symbolizes the just war and a young woman who symbolizes peace . Mucha shows the Slavs as a metaphor for peace, who first have to learn the meaning of freedom . |

| 2 | The Svantovite celebration on the island of Rügen | 1912 |

|

Mucha was inspired by the Baltic Slavs and their Svantovite cult. Rügen resisted Christianization for a long time . The picture shows the annual harvest festival, where sacrifices were made to the gods and the priest communicated with the gods. In the upper part of the picture the Germanic god Thor can be seen with his wolves, who are subjugating the Baltic Slavs. Svantovit himself raises his sword against the Germans . |

| 3 | The introduction of the Slavic liturgy | 1912 |

|

The painting focuses on the Slavic language community when Cyril and Methodius translated the Bible into Old Church Slavonic in the 8th century . Cyrill and Method are also considered to be the originators of the oldest Slavic script Glagoliza , from which the Cyrillic , which is still widespread today, developed. |

| 4th | Simeon , the tsar of the Bulgarians | 1923 |

|

When the time of the Slavic liturgy ended with the death of Methodius , the disciples found refuge at the court of the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon . He commissioned the translation of many Byzantine texts into Slavic. The Tsar is shown in a basilica, he is visited by philosophers, writers, linguists and scribes. |

| 5 | Ottokar II , King of Bohemia | 1924 |

|

Ottokar II. Přemysl was one of the most powerful kings in Czech history. Shown is the wedding ceremony of one of his nieces, to which he invited all Slavic rulers to make an alliance and to create peace. Ottokar himself welcomes two of his guests here. |

| 6th | The coronation of Stefan Dušan , King of the Serbs | 1924 |

|

Stefan Uroš IV. Dušan used the collapsing Byzantine Empire as a military leader to expand the Slavic area to the south. He was crowned Tsar of Serbs and Greeks in the 14th century . You can see the procession that followed the coronation. |

| 7th | Jan Milíč from Kremsier | 1916 |

|

Reform preacher Jan Milíč cared for the poor in Prague and converted many prostitutes. He built a monastery that was dedicated to Mary Magdalene on the site of a brothel. The figures on the scaffolding plan the monastery that cares for the poor. Milíč can be seen below on the right, preaching to a group of women who exchange their clothes for nuns' robes. |

| 8th | After the battle of Grünwald | 1924 |

|

In response to the Teutonic Order's military incursions into the northern Slavs, King Wladyslaw Jagiello of Poland and King Wenceslas IV of Bohemia signed a defense treaty . This became relevant in 1410 in the Battle of Grünwald . Mucha does not show the fight, but the many dead as a result of the battle. |

| 9 | The sermon of the master Jan Hus in the Bethlehem Chapel | 1916 |

|

In the 15th century Jan Hus appeared as a religious leader in Prague and was to become the main figure of the Reformation in Bohemia . He preached a strict, virtuous way of life and criticized the worldly possessions of the church, the greed of the clergy and their vices. Hus was burned in 1414 during the Constance Council , which sparked a Czech national rebellion, which in turn led to the Hussite Wars . Mucha shows Huss in the Bethlehem Chapel in Prague . |

| 10 | The meeting of the first Hussites "Na Křížkách" near Benešov | 1916 |

|

After the death of Johann Hus , the leadership of the Slavic religious reform movement went to the radical Hussite Utraquist preacher Václav Koranda . Koranda propagated a state of God and urged his followers to use a sword instead of a staff. Here preaching is shown in front of a meeting, the gloomy sky and the red flag indicate the soon following battles. |

| 11 | After the battle on Mount Vítkov | 1916 |

|

In the early stages of the Hussite Wars , the German king occupied Prague Castle . A peasant army of Hussites from southern Bohemia opposed the crusaders . It was led by Jan Žižka . Czech soldiers liberated the troops besieged on Vítkov Mountain , led by a monstrance-bearing priest. The priest is surrounded by praying clergymen. The woman in the foreground turns her back on the solemnity, realizing that the war will claim the lives of her sons. |

| 12 | Petr Chelčický near Vodňany | 1918 |

|

The city of Vodňany was caught in the crossfire between the Hussites and crusaders . The inhabitants fled to Petr Chelčický , a reformer who anticipated some of the points of view of Martin Luther's teaching . Chelčický has been living in retirement on his estate in South Bohemia since 1420 and developed a radically pacifist vision of Christianity. He rejected all exercise of power and violence in the church, as well as its possession. He strove for a return to early Christianity , postulated the equality of all Christians and called for voluntary poverty. In the picture, Chelčický utters thoughts of revenge on the incoming refugees. |

| 13 | George of Podebrady , King of the Hussites | 1923 |

|

The picture focuses on the triumph of the Hussite King George of Podebrady over the Crusades on Slavic territory. George was the first king in Europe to renounce Catholicism when he accepted the Hussite denomination. All of George's attempts to negotiate with the new Pope Paul failed and he was excommunicated. However, the crusades were settled in the 15th century. |

| 14th | The victim of the Croatian Ban Nikolaus Zrinski in Sziget | 1914 |

|

In the 16th century, invading Turks were stopped by a civil army provided by the Croatian nobleman Nikolaus Zrinski . After Zrinski's death, his widow blew up a gunpowder depot, stopping the Turkish army from advancing. Mucha captures the moment of the explosion in the depiction of the ongoing struggle. |

| 15th | The printing of the Kralitz Bible in Eibenschütz | 1914 |

|

In the 16th century, the first complete Czech version of the Bible was printed in Kralitz . It was translated into Czech from the original languages Hebrew and Greek and provided with a comment. In this scene, a nobleman inspects the first few pages of the printed text while a number of students gather around the printing press to the right and a student reads to a blind man. |

| 16 | The last days of Comenius in Naarden | 1918 |

|

After a military defeat in the 17th century, the Czechs were forced back to Catholicism . The writings of the pedagogue, theologian and philosopher Johann Amos Comenius inspired his compatriots to believe in a return to independence. Mucha represents his death: Comenius is sitting on a chair on the seashore in the Dutch city of Naarden . His mourning followers can be seen in the foreground. |

| 17th | Holy Mount Athos , the destination of the East Slav pilgrims | 1926 |

|

This painting pays tribute to the Greek Church that linked the Slavs with the Byzantine Empire , particularly through the missionary activities of Cyril and Method . Mount Athos pictured here is the holiest place of the Orthodox Church . On the right side you can see a group of Russian pilgrims kneeling before high priests. Angels appear in the center with small models from four Slavic monasteries. |

| 18th | The oath of the Slavic youth | 1926 |

|

In the 19th century the patriotic youth organization Omladina was founded with a liberal, anti-clerical orientation. Mucha shows members of the movement taking a patriotic vow under a linden tree occupied by a goddess . Mucha's own children were the models for two figures in the foreground: on the right his son Jiří , on the left his daughter Jaroslava. The motif of the girl playing the harp is similar to the one on the exhibition poster from 1928. |

| 19th | The abolition of serfdom in Russia | 1914 |

|

In Russia was serfdom by Alexander II. In 1861 abolished until very late. Often this was not followed by freedom for the peasants , but increased economic dependency, without, however, enjoying the old legal protection. The painting shows unsettled Russian peasants in front of whom an official reads the edict. The St. Basil's Cathedral and behind it the Kremlin are barely visible through a thick fog. |

| 20th | Apotheosis . Slavdom for humanity | 1926 |

|

The final painting unites the series by portraying a vision of Slavic triumph as a model for all of humanity. The blue in the lower right corner represents the mythical early days. The red in the upper left corner indicates the Hussite Wars . Dipped in yellow in the middle are those who strive for freedom, peace and unity. The youngsters holding branches of the linden tree pay tribute to the Slavic heroes. The main character, the man with outstretched arms, represents both the suffering of the Slavs over the centuries and the hopes for the new republic. Christ at the head blesses the entire scene. |

intention

With the paintings, Mucha wanted to express his love for his people, combined with a vision of humanity. The artist says of the underlying intentions: “The purpose of my work was [...] to build up, to build bridges, because we must all feed the hope that all of humanity will come closer to one another, and all the more easily when they meet get to know each other. ". There are national epics with almost every people, the genre underlines the “narrative and episodic elements” of a culture , “all epics, however, have a very specific, common internal model [...] with all their diversity: trust in the intellectual and human progress of the Humanity". The cycle is close to the Pan-Slavic approach, which wanted to achieve a cultural, historical and ideal bond in the Slavic world, but in fact remained a utopia .

reception

Mucha valued the Slav Epic itself much more highly than his previous decorative works. While the Slavic epic was celebrated and praised abroad (especially in the USA ), it was mocked and rejected in what was then Czechoslovakia . The Slav Epic was or seemed out of date and “inappropriate” at the time. This can be explained by the social awareness of the production time, because Mucha belonged to both the 19th and 20th centuries: In the second half of his life, he is not so easy to classify into a fixed art epoch. The military images are deliberately kept completely non-violent, and it is precisely this bloodless representation that could be used as the reason why “nationalist circles could never really get excited about this 'national epic'”. "The Prague internationally oriented avant-garde had [...] rejected it". For a long time, the cycle of paintings was ignored by research worldwide because it "finally stood outside of art history ".

Exhibitions

From 1928 the pictures were mostly exhibited in the Prague Exhibition Center. They were archived in the 1930s and were therefore not accessible to the public for a long time. From 1963 the pictures could be presented again in the Moravský Krumlov Castle . From 2012 to 2014 the paintings were exhibited again in Prague in the Messepalast. The negotiations and discussions about the location are reflected in Czech press releases. In 2016 the cycle of paintings was in the Prague National Gallery . In 2018, parts of the epic were exhibited in Brno along with some of Mucha's poster creations .

literature

- Karel Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Kunsthalle Krems, Krems 1994, ISBN 3-901261-01-X .

Web links

- Website for the exhibition in Brno until the end of 2018 mucha.brno.cz/de.

- Video on the exhibition setup Facebook page for the Brno exhibition 2018.

- Muchafoundation.org: The Images of the Slav Epic All motifs of the epic, made available by the Mucha Foundation (information in English).

- Radio.cz: Alfons Mucha's vision of Slavic and Czech history A special from Radio Praha on the Slavic epic.

Individual evidence

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 22.

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 22.

- ↑ muchafoundation.org

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 24f.

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, pp. 22-24.

- ↑ muchafoundation.org

- ^ Alfons Mucha: Introduction. 1928. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 63.

- ↑ a b c M. Kachlikova: Special - Slavic epic: Alfons Mucha's vision of Slavic and Czech history. Radio Praha 2012. Accessed September 8, 2012.

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 25f.

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 34.

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 26.

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 27.

- ↑ Alfons Mucha Slovanská epopej. Museum guide of the Messepalastgallerie

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ muchafoundation.org

- ↑ john-price.me.uk

- ↑ G. Mucha, J. Mucha: About the project. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 7.

- ^ A. Mucha: Introduction. 1928. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 63.

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 37.

- ↑ E. Vyslonzil: Alfons Mucha's "Slavic Epic" against the background of Czech-style pan-Slavism. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1944, p. 155.

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 22.

- ↑ L. Bydzovska, K. Srp: Orbis pictus Alfons Mucha. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 22.

- ↑ W. Denk: Myths, Historical Imaginations and Humanistic Message. The Slav Epic - a national epic - from today's perspective. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 13.

- ↑ W. Denk: Myths, Historical Imaginations and Humanistic Message. The Slav Epic - a national epic - from today's perspective. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 11.

- ↑ M. Petricek: Mucha between the times. In: K. Srp (Ed.): Alfons Mucha. The Slav Epic. Krems-Stein 1994, p. 19.

- ↑ Marco Zimmermann: Fight for Slav Epic: Moravský Krumlov has the castle renovated | Radio Prague In: radio.cz , August 6, 2012, accessed on August 30, 2018.

- ↑ mucha.brno.cz ( Memento of the original dated August 23, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.