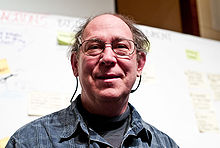

Stephen Schneider

Stephen Henry Schneider (born February 11, 1945 in New York City , † July 19, 2010 , London , Great Britain ) was an American plasma physicist and one of the most internationally influential climate scientists of his time. He worked in climate research for over 40 years and has written over 450 scientific publications. Among other things, he was one of the first scientists to work with satellite data-based climate models for predicting human impact on the global climate. Schneider has been a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ( IPCC) and coordinating lead author for several status reports since its inception . He was the founder and editor of the journal Climatic Change , author of several specialist books and scientific advisor to eight US governments . Early on in his career, he was concerned with the question of how best to communicate scientific knowledge about climate change to the public. He was a committed advocate of climate action and a leading figure in the political controversy surrounding global warming . The Stephen H. Schneider Award for outstanding achievements in climate science communication is named after Schneider .

Life

Youth and Studies

Schneider grew up on Long Island , New York . He has been interested in astronomy since his youth . He studied at Columbia University in New York City First Engineering (bachelor's degree in 1966) and in the master's program in addition plasma physics (master's degree in 1968). After the student unrest of 1968, Schneider was elected deputy chairman of the newly established student committee in the university's senate because of his balanced stance. During his studies, Schneider initially focused on rocket propulsion .

Climate change and climate models

The Earth Day 1970 focused his attention on climate change , which he described as "grandmother of all environmental problems." While still at Columbia University, he attended seminars with Joseph Smagorinsky and Ishtiaque Rasool , which sparked his interest in climate models . As a result, after completing his doctorate in 1971, he moved to the Goddard Institute for Space Studies at NASA in mechanical engineering and plasma physics , where James E. Hansen was also active at the same time .

In the early 1970s, satellite data for climate modeling and computers for evaluating them were available for the first time , and at that time there was almost no one involved in climate models.

Role of aerosols

In his first publications, Schneider, together with Ishtiaque Rasool, dealt with the effects of anthropogenic aerosols (emissions from industry, e.g. soot particles ) on the global climate. His results on the basis of the evidence at the time and early methods of climate modeling led him to the assessment that the cooling effects of aerosols could possibly dominate the warming effects of greenhouse gases, which would result in global cooling. A publication on this in the journal Science brought him a lot of attention, misinterpretation and criticism.

A few years later it became clear that the cooling effects of aerosols only have a regional effect, and the warming effect of greenhouse gases dominates globally. In 1975, Schneider was the first to correct his own results from 1971 on the basis of new empirical data and with the help of new climate modeling methods. Schneider later stated that he was proud to have realized together with colleagues why their first assumption was unlikely and the opposite conclusion was the better one. He described this as an "early example of scientific skepticism in action in climatology".

Together with Cliff Mass, Schneider also looked at another type of aerosol - sulfuric acid emitted by volcanic eruptions - and their influence on the climate.

First experiences with the media

In connection with his controversial Science article, Schneider wrote what was probably his first reading letter to the New York Times , published on September 16, 1971. In it he criticized the author of an Op-Ed article (an engineer) for his "often imprecise and certainly misleading conclusions". Among other things, he described the influence of carbon dioxide on air temperature as "idiocy" and made fun of the fact that humanity was now either "roasted to death" or "frozen to ice". Schneider explained that previous research suggests that humans can influence the climate through aerosols and greenhouse gases - it is just not yet known exactly which effect is stronger. He called for more research and international collaboration on the subject.

After a lecture in 1972 at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science , Schneider made a humorous comment on the above. Subject cited the following day by renowned science journalist Walter Sullivan in the New York Times , which brought Schneider public attention unusually early in his career. From then on, he began to focus on how to convey both the urgency and the uncertainties surrounding global warming to the public without exaggerating or understating. He reported on his experiences with this in his book Science as a Contact Sport: Inside the Battle to Save Earth's Climate .

Role of cloud formation

In 1972 Schneider received a scholarship for post-graduate students and moved to the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado , where he was permanently employed from 1973 to 1996. After his time as a Fellow in the Advanced Study Program, he was chairman of the program and in the 1980s as a Senior Scientist at NCAR, where he co-founded the NCAR's Climate Project .

In addition to his work on aerosols, Schneider also dealt with the role of cloud formation as a climatic feedback mechanism from the early 1970s . He pointed out that not only the change in the number of clouds, but even very small changes in the height of the clouds result in significant climatic changes. Schneider was the first to use a very detailed estimate of the radiation transfer to show that this feedback mechanism is a major source of uncertainty in climate predictions. His estimates of the strength of the cooling effect of clouds were confirmed in subsequent studies.

Role of the oceans

From the beginning of the 1980s, Schneider - initially together with Starley Thompson and later with Danny Harvey - dealt with the role of the oceans in modulating anthropogenic global warming, a question that had hardly been investigated until then. They were able to show that a slow heat transfer into the deeper layers of the ocean results in a delay in climatic changes by a decade or more. Oceans do not have the same depth everywhere and do not cover the same floor area at every depth, which leads to regionally different rates of delay in the response of the climate system to greenhouse gases. The resulting temperature gradients could in turn affect the atmospheric circulation .

Methodological aspects of climate modeling

Parallel to content-related predictions, Schneider also dealt with methodological and statistical aspects of climate modeling in the 1970s, in particular with the signal-to-noise ratio . Every “signal” - such as a coherent, slowly evolving warming signal in response to the gradual increase in greenhouse gas concentrations caused by humans - is embedded in the strong “ background noise ” of natural climate variability. Schneider and his colleagues dealt with the question of how “loud” the signal has to be so that it can be distinguished from noise, and which strategies are useful to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. He used u. a. the method of "ensemble averaging". In this context, he also addressed the question of when and where to look for the first signs of anthropogenic global warming, and pointed out the need for time-dependent simulations with a coupled atmosphere-ocean model that reflects geography and realistically depicts the increase in CO 2 . This first work on this topic established a separate field of research, and many of the findings from that time were still relevant 40 years later.

Climatic change

In 1975 Schneider founded the specialist journal Climatic Change - the first specialist journal on climate change up to that point - of which he was editor until his death. He was also involved in founding the Sustainability Science section of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Possible effects of nuclear war on the climate

In the early 1980s, the first articles were published (including by Paul R. Ehrlich , John P. Holdren and Paul Crutzen ) on the potential climatic and ecological consequences of a nuclear war . Through his work on aerosols, Schneider was able to calculate the climatic effects of uncontrollable fires that would be set off by a nuclear explosion. In addition, based on his earlier work, he included the effects of ocean circulation in his climate models. As a result, Schneider and his working group did not predict a nuclear winter (with a temperature drop of 25 - 30 ° C) like other authors , but only a "nuclear autumn" with a temperature drop of 5 - 15 ° C.

Move to Stanford

Since 1992 Schneider was a professor at Stanford University . There he founded the interdisciplinary Environmental Institute together with 60 colleagues . He held a "Melvin and Joan Lane" professorship in interdisciplinary environmental sciences and a professorship in the Department of Biology. He was also a Senior Fellow of the Woods Institute for Environmental Sciences and had an additional professorship in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering .

Communication of statistical uncertainty

He began to deal with the communication of statistical uncertainty as well as the public perception of the risks of global warming, especially in the context of the uncertainties in the modeling of the interactions between human and natural systems and also contributed to a unified description of the treatment of uncertainty in the IPCC process .

IPCC and policy advice

Schneider was a long-time employee of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change , which together with Al Gore received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 . Involved as an author from the first assessment report , from 1994 to 1996 he was lead author in working group I for the second assessment report , and from 1997 to 2001 coordinating lead author of working group II for the third assessment report . He was also involved in the fourth status report as coordinating lead author of Working Group II and in the preparation of the summary report (“Synthesis Report”).

Schneider has also advised US federal agencies and / or the White House under the governments of Richard Nixon , Gerald Ford , Jimmy Carter , Ronald Reagan , George HW Bush , Bill Clinton , George W. Bush and Barack Obama .

Cancer and private matters

In 2001 Schneider was diagnosed with a rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma ( mantle cell lymphoma ). Schneider reported on his experiences with cancer treatment in his book The Patient from Hell , published in 2005 .

He died of a heart attack in 2010 on a flight from Gothenburg to London , on his way back from a conference on the Swedish island of Käringön, at the age of 65 .

Schneider was most recently married to the biologist Terry Root, with whom he also worked repeatedly. He had a son and a daughter from a previous marriage.

Awards and memberships

In 1992 he was awarded the MacArthur Fellowship for his contributions to communicating global warming. From 1999 to 2001 he was Chairman of the Atmospheric and Hydrosphere Science Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science . In 2002 he was accepted into the US National Academy of Sciences . In 2003 he and his wife received the National Conservation Achievement Award from the National Wildlife Federation .

Various events have taken place in memory of Stephen Schneider since his death. At a memorial service in December 2010, John Holdren and Naomi Oreskes, among others, spoke . Schneider's wife, Terry Root, organized a three-day Stephen H. Schneider Symposium at the National Center for Atmospheric Research together with Benjamin Santer , Jean-Pascal van Ypersele and others in August 2011 . A Steven Schneider Memorial Lecture has been held annually at Stanford University since 2013 . On the occasion, Al Gore spoke in 2013 and Lisa P. Jackson in 2014 .

In July 2014, it was announced that Schneider would be inducted into the California Hall of Fame at the California Museum.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) dedicated the synthesis report of its fifth assessment report to Stephen Schneider. Schneider is referred to as "one of the leading climate scientists of our time" and his great importance for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is presented.

The Stephen H. Schneider Award , which is given for "outstanding climate science communication", was named after Schneider . Prize winners include a. James E. Hansen , Nicholas Stern , Naomi Oreskes, and Michael E. Mann .

Schneider's role in climate communication

When global warming came into public interest after the heat wave in 1988, Schneider gave many interviews. He was increasingly frustrated by the often shortened presentation of complex facts in the media. In an interview with Jonathan Schell published in the popular science monthly Discover in October 1989 , he said:

"On the one hand, as scientists we are ethically bound to the scientific method, in effect promising to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but - which means that we must include all doubts, the caveats, the ifs, ands and buts. On the other hand, we are not just scientists but human beings as well. And like most people we'd like to see the world a better place, which in this context translates into our working to reduce the risk of potentially disastrous climate change. To do that we need to get some broad based support, to capture the public's imagination. That, of course, means getting loads of media coverage. So we have to offer up scary scenarios, make simplified, dramatic statements, and make little mention of any doubts we might have. This “double ethical bind” we frequently find ourselves in cannot be solved by any formula. Each of us has to decide what the right balance is between being effective and being honest. I hope that means being both. "

“On the one hand, we as scientists are ethically bound to the scientific method, that is to say the truth, the whole truth and nothing but that - including all our doubts, reservations, if's, and's, and but's. On the other hand, we are not only scientists, but also human beings. And like most people, we would like to see the world as a better place, which in this context means that we want to reduce the risk of potentially catastrophic climate change. To do that, we need broad support, we need to get the public to get an idea. A lot of media reports are necessary for this. So we have to provide frightening scenarios, make simple, dramatic utterances, and little mention of any doubts we may have. This “ethical double bond” in which we often find ourselves cannot be resolved by any formula. Each of us must decide what is the right balance between being effective and being honest. I hope it comes down to both. "

The Detroit News subsequently published an article on November 22, 1989, in which the interview was quoted, but only excerpts and distorting the meaning - among other things, Schneider's last sentence was omitted. Schneider wrote a correction that was published a month later. In the meantime, however, the selectively abbreviated quote has been cited many times over. As a result, Schneider was repeatedly accused in the following 15 years - for example by the economist and member of the Cato Institute Julian L. Simon - that he did not take the truth so strictly and advocated exaggerations.

After Schneider published his book Science as a Contact Sport: Inside the Battle to Save the Earth's Climate in 2009 and spoke about the hacking incident at the University of East Anglia's climate research center in an interview , he was at a press conference at the UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen 2009 by a stranger who had entered the stage without permission yelled at several times whether he was in favor of the deletion of data. Schneider reported in the summer of 2010 that he had received hundreds of "hate" emails, some of which were threatening.

Works (selection)

- with Michael D. Mastrandrea (2010), Preparing for Climate Change , MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-01488-2

- Stephen H. Schneider, Armin Rosencranz, Michael D. Mastrandrea and Kristin Kuntz-Duriseti (eds.), Climate Change Science and Policy , Island Press , Washington, DC 2009

- Science as a Contact Sport: Inside the Battle to Save the Earth's Climate , 2009, ISBN 978-1-4262-0540-8

- with Janica Lane, The Patient from Hell: How I Worked with My Doctors to Get the Best of Modern Medicine and How You Can Too . Da Capo Lifelong Books 2005

- Stephen H. Schneider, Armin Rosencranz, John O. Niles (Eds.), Climate Change Policy: A Survey , Island Press 2002

- Stephen H. Schneider and Terry L. Root (Eds.), Wildlife Responses to Climate Change: North American Case Studies , Island Press 2001

- Laboratory Earth: the Planetary Gamble We Can't Afford to Lose , HarperCollins 1997

- Stephen H. Schneider (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Climate and Weather , Oxford University Press 1996

- Stephen H. Schneider, Penelope J. Boston (Eds.), Scientists on Gaia , MIT Press 1992

- Global Warming: Are We Entering the Greenhouse Century? , Sierra Club Books 1989

- with Randi Londer, Coevolution of Climate and Life , Sierra Club Books 1984

- with Lynne E. Mesirow, The Genesis Strategy: Climate and Global Survival , Plenum Pub Corp. 1976

Literature on Stephen Schneider

- Regina Nuzzo: Profile of Stephen H. Schneider . In: PNAS . 102, No. 44, 2005, pp. 15725-15727. doi : 10.1073 / pnas.0507327102 .

- Paul R. Ehrlich : Stephen Schneider (1945–2010) . In: Science . 329, No. 5993, 2010, p. 776. doi : 10.1126 / science.1195502 .

- Michael D. Mastrandrea: Stephen Henry Schneider (1945-2010). A voice of reason in climate-change science and policy . In: Nature . 466, August 19, 2010, p. 933.

- Benjamin D. Santer , Susan Solomon : Stephen H. Schneider (1945-2010) . In: Eos . 91, August 19, 2010, p. 372.

- IPCC : IPCC In Memoriam: Stephen Schneider, 1945-2010 , 19 July 2010.

- William RL Anderegg: Stephen H. Schneider: In Memoriam . In: Thought & Action: Magazine of the National Education Association . , Pp. 33-34.

- Benjamin D. Santer, Paul R. Ehrlich: Stephen Schneider 1945 - 2010 . A Biographical Memoir. National Academy of Sciences , 2014.

Web links

- Stephen Schneider website with his biography

- The Stephen H. Schneider Collection : Online Archive of California

- National Center for Atmospheric Research : Stephen Schneider: An extraordinary life .

- Schneider's speech on the media distortion of the scientific discussion on climate change , November 2009.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Douglas Martin: Stephen H. Schneider, Climatologist, Is Dead at 65 . In: The New York Times . July 20, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ↑ IPCC : IPCC In Memoriam: Stephen Schneider, 1945-2010 , July 19, 2010.

- ^ T. Rees Shapiro: Stephen H. Schneider, climate change expert, dies at 65 . In: Washington Post . July 20, 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Benjamin D. Santer : A Eulogy to Stephen Schneider . In: RealClimate . July 19, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Regina Nuzzo: Profile of Stephen H. Schneider . In: PNAS . November 1, 2005. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Benjamin D. Santer , Paul R. Ehrlich: Stephen Schneider 1945 - 2010 . A Biographical Memoir. National Academy of Sciences , 2014.

- ^ S. Ishtiaque Rasool, Stephen H. Schneider: Atmospheric carbon dioxide and aerosols: Effects of large increases on global climate. . In: Science . 173, No. 3992, 1971, pp. 138-141. doi : 10.1126 / science.173.3992.138 .

- ↑ a b Michael D. Mastrandrea: Stephen Henry Schneider (1945-2010). A voice of reason in climate-change science and policy . In: Nature . 466, August 19, 2010, p. 933.

- ↑ Stephen H. Schneider, Cliff Mass: Volcanic dust, sunspots, and temperature trends . In: Science . 190, 1975, pp. 741-746.

- ^ Gavin Schmidt : Steve Schneider's first letter to the editor . In: RealClimate . April 25, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2015. (with links to the original articles)

- ^ Walter Sullivan: Goals for US Urged On Weather Control . In: The New York Times . December 29, 1972. Accessed July 25, 2014. (not accessible)

- ↑ Science and media: Climate researchers criticize supposedly balanced journalism . In: Spiegel Online . February 17, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ↑ a b c d e Stephen Schneider, a leading climate expert, dead at 65 . Stanford University . Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ Stephen H. Schneider: Cloudiness as a global climate feedback mechanism: The effects on the radiation balance and surface temperature of variations in cloudiness. . In: Journal of Atmospheric Sciences . 29, 1972, pp. 1413-1422.

- ↑ Stephen H. Schneider, WM Washington, Robert M. Chervin: Cloudiness as a climatic feedback mechanism: Effects on cloud amounts of prescribed global and regional surface temperature changes in the NCAR GCM. . In: Journal of Atmospheric Sciences . 35, 1978, pp. 2207-2221.

- ↑ Starley L. Thompson, Stephen H. Schneider: Atmospheric CO 2 and climate: Importance of the transient response. . In: Journal of Geophysical Research . 86, 1981, pp. 3135-3147.

- ↑ Starley L. Thompson, Stephen H. Schneider: Carbon dioxide and climate: Ice and ocean. . In: Nature . 290, 1981, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Starley L. Thompson, Stephen H. Schneider: CO 2 and climate: The importance of realistic geography in estimating the transient response. . In: Science . 217, 1982, pp. 1031-1033.

- ↑ LDD Harvey, Stephen H. Schneider: Transient climate response to external forcing on 1-1000 year time scales. Part I: Experiments with globally averaged, coupled, atmosphere and energy balance models. . In: Journal of Geophysical Research . 90, 1985, pp. 2191-2205.

- ↑ LDD Harvey, Stephen H. Schneider: Transient climate response to external forcing on 1-1000 year time scales. Part II: Sensitivity experiments with a seasonal, hemispherically averaged coupled atmosphere, and ocean energy balance model. . In: Journal of Geophysical Research . 90, 1985, pp. 2207-2222.

- ^ Robert M. Chervin, W. Lawrence Gates, Stephen H. Schneider: The effect of time averaging on the noise level of climatological statistics generated by atmospheric General Circulation Models . In: Journal of Atmospheric Sciences . 31, 1974, pp. 2216-2219.

- ^ Robert M. Chervin, Stephen H. Schneider: On determining the statistical significance of climate experiments with General Circulation Models . In: Journal of Atmospheric Sciences . 33, 1976, pp. 405-412.

- ^ Robert M. Chervin, Warren M. Washington, Stephen H. Schneider: Testing the statistical significance of the response of the NCAR General Circulation Model to North Pacific ocean surface temperature anomalies . In: Journal of Atmospheric Sciences . 33, 1976, pp. 413-423.

- ↑ cf. en: Ensemble averaging

- ↑ Starley L. Thompson, Stephen H. Schneider: Carbon dioxide and climate: Has a signal been observed yet? . In: Nature . 295, No. 5851, 1982, pp. 645-646. doi : 10.1038 / 295645a0 .

- ^ Peter H. Gleick: Dr. Stephen Schneider, Climate Warrior . In: The Huffington Post . July 19, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ Myles Allen: Stephen Schneider obituary . In: The Guardian . July 20, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ↑ C. Covey, Stephen H. Schneider, Starley L. Thompson: Global atmospheric effects of massive smoke injections from a nuclear war: Results from General Circulation Model simulations . In: Nature . 308, 1984, pp. 21-25.

- ↑ Starley L. Thompson, VV Aleksandrov, GL Stenchikov, Stephen H. Schneider, C. Covey, Robert M. Chervin: Global climatic consequences of nuclear war: simulations with three-dimensional models . In: Ambio . XIII, 1984, pp. 236-243.

- ↑ Stephen H. Schneider, Starley L. Thompson, C. Covey: The mesoscale effects of nuclear winter . In: Nature . 320, 1986, pp. 491-492.

- ↑ Stephen H. Schneider, Starley L. Thompson: Simulating the climatic effects of nuclear war. . In: Nature . 333, 1988, pp. 221-227.

- ^ Andrew Revkin: The Passing of a Climate Warrior . In: The New York Times . July 19, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ a b c Stephen H. Schneider (In Memoriam) . Woods Institute for the Environment, Stanford University . Archived from the original on March 14, 2018. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ↑ Pennington P. Ahlstrand: The Stephen H. Schneider Collection . Stanford University Libraries, April 9, 2014.

- ^ Memorial Program Celebrating the Life of Steve Schneider. December 12, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Stephen H. Schneider Symposium: Climate Change - from Science to Policy. 24.-27. August 2011, Boulder, CO. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ At Stanford, Al Gore connects climate change inaction to political dysfunction. Stanford Report, April 24, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "The Private Sector as Public Servant": Stephen H. Schneider Memorial Lecture featuring Lisa Jackson. ( Memento of the original from June 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Stanford Woods Institute of the Environment. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Late Stanford climate expert to be inducted into California Hall of Fame . Stanford University. July 24, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ Stephen Schneider . California Museum. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ↑ IPCC : Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2014 (page 11). Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ↑ 2017 Stephen H. Schneider Award bestowed upon Dr. Michael Mann . Climate One. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Julian L. Simon: Resources and Population: A Wagner . (PDF) In: APS News . 5, No. 3, 1996, p. 12.

- ↑ Stephen H. Schneider: Don't Bet All Environmental Changes Will Be Beneficial . In: APS News . 5, No. 8, 1996. (Schneider replica of Simon's article).

- ↑ Stephen H. Schneider: "Mediarology": The Roles of Citizens, Journalists, and Scientists in Debunking Climate Change Myths. On: stephenschneider.stanford.edu. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ↑ Stephen Schneider: Climate Scientist Harassed, Verbally Attacked At UN Press Conference (VIDEO) . California Museum. March 18, 2010. Accessed August 31, 2015.

- ^ Facing the Heat. Climatologist Stephen Schneider calls for cooler heads as temperatures, and tempers, rise . Stanford University. July 2010. Accessed August 31, 2015.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tailor, Stephen |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schneider, Stephen Henry |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American climatologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 11, 1945 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New York City |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 19, 2010 |

| Place of death | United Kingdom |