Street art

As Street (also: street art , rare as misleading street art . See there ) different, mostly non-commercial forms of public art called that should permanently remain there after the intention of the perpetrator entirely. Street art is understood to be self-authorized signs of all kinds in urban space that want to communicate with a wider group of people. The narrower or broader understanding of the term street art is linked to its commercial usability. In contrast to graffiti , the image part often predominates, not the artistic writing / painting of one's own name.

Origin and origins

Since 2005, street art has been a term encompassing various techniques, materials, objects and forms of art in public spaces. According to this, several art movements can be cited that have an influence on the design of street art. 1968 was one of the first major Wall Paintings in Hamburg at the Große Freiheit by Werner Nöfer and Dieter glassmakers . From around 2000 street art is a movement, before that only individual artists did what has been called street art since around 2005. Before that, terms like post graffiti or urban art competed with street art.

In addition to the authorized scratching work from Pompeii , one of the first known lettering in the urban area is Kyselak by Joseph Kyselak , who left his name on the walls while traveling in the 19th century. Similar to the slogan Kilroy was here from the 1940s and 1950s (with roots in World War I), it is the early graffiti that was either scratched into the wall or painted on the wall. American graffiti or style writing differs from street art in a narrower sense. Urban art often functions today as an umbrella term for street art, graffiti and art in public space or public art . In the media and artist interviews, street art, public art, urban art and graffiti are often not differentiated.

Many street artists come from the graffiti or punk scene. In addition to graffiti, outdoor advertising is said to be the closest relative of street art. In the course of the industrial revolution, a market for advertising in the form of painted advertisements on house facades emerged. Propaganda art, like poster and facade advertising, has a stylistic effect on street art. Shepard Fairey , for example, uses military art as a stylistic device in his works.

Artistic specific

The artists use various media (markers, brushes and paint rollers, spray cans , stickers , posters, etc.) to present their works. Walls are often painted and pasted, but power boxes, lanterns, traffic signs, telephone booths, trash cans, traffic lights and other street furniture , as well as sidewalks and streets themselves and even trees - in principle, every imaginable surface - are designed. Street art is usually limited to the design of existing areas. Since the techniques of street art often overlap with those of graffiti , it is difficult to distinguish between the two terms these days.

Although commissioned works by private property owners or municipalities such as Blek le Rat , Tribute to Tom Waits in Wiesbaden (1983), the works are mostly illegally attached. That is why most artists prefer to remain anonymous - members of the scene often only know each other by their pseudonyms .

For many, the motivation lies in having fun and being able to visually shape their own environment in an anarchistic and / or creative way (compare Reclaim the Streets ), as well as to create an artistic counterpoint to omnipresent advertising or gentrification ; For many, the egocentric tendency to spread one's (artist) name as often as possible also plays a role (see Joseph Kyselak ). In terms of content, street art often turns against consumerism , capitalism and public order . Most artists, however, forego a specific message - “the medium is the message” (according to Marshall McLuhan ).

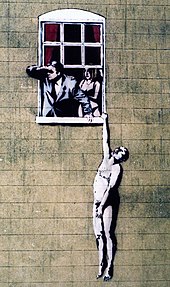

The French Gérard Zlotykamien is considered to be the first artist to work in this way in public spaces and is therefore the forefather of street art. Other important artists in this genre include Keith Haring , Harald Naegeli , Werner Nöfer , Blek le Rat , Miss.Tic , Banksy , Blu , Os Gêmeos & Nina , John Fekner and Klaus Paier .

Image examples of different techniques

Stencil graffito by WATTTS in Paris

Early street art by Jacek Tylicki , Lower East Side , New York, USA. 1982

Mural by The London Police

Character of Monsieur A

Installation by the American artist Mark Jenkins

Commercialization

In recent times, the means of expression of street art have also been used by companies both in terms of their style and in their entirety as advertising media in order to give their products a youth cultural image. The most widespread is the affixing of advertising stickers, which originally emerged from the sticker art scene. Many shops from the alternative scene distribute free stickers to their customers in order to get satisfied customers to "advertise". The sporting goods manufacturer Nike in particular is known for wildly placarded advertising stickers and large-scale murals that are initially not perceived as commercial advertising. The pocket web provider Ogo was also at times strongly present in the public cityscape with its guerrilla marketing in the form of graffiti, stickers and paste-ups. The Sony company even set up a street art gallery to market the PSP in Berlin-Mitte, which was seen as a nuisance, especially by the surrounding art scene.

In the street art scene, this form of advertising is often criticized as the appropriation of a youth cultural identity and meets with resistance above all, since the origin of street art is understood, among other things, as a fight against capitalism and consumer society as well as the abandonment of the privatization of urban spaces.

However, the discourse about the commercialization of street art is also criticized. According to the social scientist Hans-Christian Psaar, the relationship between the market and street art is more complex than the sale of street art to large corporations. The sociologist Jens Thomas especially draws attention to the fact that a “consumer and socially critical self-image” of street art actors is conveyed by the media and corporations. Anti-capitalist attitudes could themselves have “capitalist connotations”, since “demarcation” is produced as a good.

Street art on social media

In the past it was graffiti and street art magazines such as Backspin , which spread art in public spaces and mostly only served the scene clientele. In recent years, with the advent of Web 2.0, there has been an exponential spread of the Art form on the internet and especially on social media. The importance of this cooperation between street art and social media is particularly evident when one searches Google for the term combination “street art Facebook”. With around 346,000,000 hits (as of February 22, 2018), this illustrates the increasing relevance of social media and street art.

The most famous internet platform for street art in German-speaking countries is therefore also on Facebook . The “Streetart in Germany” site, launched by Timo Schaal, has meanwhile become the “hotspot on the social web for all street art enthusiasts”. Here it is no longer the site operator alone who takes care of the content and publication of the images. Fans from all over the world, but also artists do the rest and provide a prime example of the possibilities that Web 2.0 offers. One thing is certain: street artists have discovered the Internet for themselves. If you consider the origin and actual intention of the art form street art (or graffiti ), starting points can certainly be found, which is why this cooperation is being intensified more and more. Works are made available to the general public (cities / internet), but this is as hidden as possible under the protection of the night or the crowd. Because even on the Internet, artists rarely reveal their identity. The best-known example of this is certainly the street artist Banksy . The street art icon has always tried to keep its identity a secret. As a result, the entire art world asks itself who is this brilliant street artist. In addition, Banksy's mysterious approach is certainly fueling its hype.

Another thing that social media and street art have in common, according to Banksy, is the actual core intention: "Free art for everyone that makes people think". Above all, socially critical issues are addressed. The Artist Above was z. B. in a short time-lapse film with the social media and questioned them, as they occupy an ever-increasing part of our lives. Here he alienated well-known media logos and phrases and put his artistic stamp on them. Among other things, he sprayed various phrases that recur in Facebook on a wall: "#my life sucks #im bored #waste of time #imLonely #irony #reblog this shit #wtf #wish you were here #LOL #lmfao #stupid" . The combination of social media and street art has meanwhile also reached the mobile web . So three young people from Istanbul have made it their business to create a mobile platform for street art in their Turkish hometown. The cooperation between the artist, the designer and the software programmer went so far that there is now a street art app for Istanbul. This presents the works of art and locates them on maps. The images are synchronized online on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram and distributed on the Internet. From a group of street art artists from Antwerp and Heerlen , the “Street Art Cities” has existed since the beginning of 2017, an international digital community that has now grown to 100 cities worldwide and is constantly growing. The individual cities can be clicked on on a world map. Photographed works of art, artists and routes are listed and described. Every city has local street art hunters.

Street art is difficult to exhibit in art museums. Photographs do justice to street art to a limited extent, as they cannot convey the dimensions and the mostly decisive environment in which they are to be found. The virtual museum - Universal Museum of Art has taken on this problem and developed a street art exhibition "A Walk Into Street Art", in which a virtual art exhibition with famous street art motifs can be visited, which shows the works as possible in their natural, free environment reproduces in its dimensions. Artists like Banksy , JR , Jef Aérosol , Vhils , Shepard Fairey , Keith Haring etc. are represented here.

See also

literature

- Michael Naumann : "Werner Nöfer - Street Art" ZEIT Magazine 3/1970.

- Horst Schmidt Brümmer: "The painted city - initiatives to change the streets in the USA / Examples in Europe", M.DuMont Schauberg publishing house, Cologne 1973 ISBN 3-7701-0719-5

- Jörgen Bracker : "The change in the republic or a theory of architecture", catalog of the Museum for Hamburg History "Das Strassenmuseum" for the exhibition Werner Nöfer (p. 28–39) Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-00-002497-2

- Ulrich Behm: Property damage and disfigurement. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-428-05644-2 .

- Ulrich Blanché: Something to s (pr) ay: The Street Artivist Banksy: An Art History Research. Tectum Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8288-2283-2 .

- Sandra Maria Geschke: Street as a cultural space for action: interdisciplinary considerations of street space at the interface between theory and practice. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-531-16212-6 .

- Katja Glaser: Street Art and New Media. Actors - Practices - Aesthetics . Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2017, ISBN 978-3-8376-3535-5 .

- Christian Heinicke, Daniela Krause: Street Art. The city as a playground. Tilsner, Bugrim 2006, ISBN 3-86546-040-2 .

- Marcel Hennes, Alexandra Pätzold, Gerhard Pätzold (eds.): Streetart Marburg. Jonas Verlag for Art and Literature, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-89445-406-7 .

- Christian Hundertmark: The Art of Rebellion I / II. Publikat-Verlag, Aschaffenburg 2003, ISBN 3-9807478-3-2 or ISBN 3-9809909-4-X .

- Kai Jakob: Street Art in Berlin - Version 7.0. Jaron Verlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-89773-778-5 .

- Katrin Klitzke, Christian Schmidt (Ed.): Street Art. Legends to the street. Verlag Archiv der Jugendkulturen eV, 2009, ISBN 978-3-940213-44-0 .

- Uwe Lewitzky: Art for everyone? - Art in public space between participation, intervention and new urbanity. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-89942-285-6 .

- Christoph Mangler: Berlin City Language. Prestel, 2006, ISBN 3-7913-3610-X . (engl.)

- Julia Reinecke: Street Art - A subculture between art and commerce. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-89942-759-2 .

- Jan P. Schildwächter, Britt Eggers: Street Art Hamburg. Junius, Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-88506-582-1 .

- Kai Hendrik Schlusche: Graffiti under the motorway; The Bridge Gallery in Loerrach . Verlag Waldemar Lutz, Lörrach 2011, ISBN 978-3-922107-91-0 , p. 112 .

- Nora Schmidt: The sidewalk as a gallery. A contribution to the sociological theory of street art . Publishing house Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8300-4433-8 .

- Horst Schmidt-Brümmer: Venice, California . Against culture through imagination. Ernst Wasmuth, Tübingen 1972, ISBN 3-8030-0121-8 .

- Robert Sommer: Street Art. Links, New York / London 1975, ISBN 0-8256-3044-4 .

- Johannes Stahl: Street Art. Königswinter 2009, ISBN 978-3-8480-0075-3 .

- Bernhard van Treeck , Sibylle Metze-Prou: Pochoir - the art of stencil graffiti. Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-89602-327-6 .

- Bernhard van Treeck: Street Art Berlin. Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-89602-191-5 .

- Bernhard van Treeck: Street Art Cologne. Edition Aragon, Moers 1996, ISBN 3-89535-434-1 .

- Claudia Walde: Sticker City: Paper Graffiti Art (Street Graphics / Street Art). Thames & Hudson, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-500-28668-5 .

- André Lindhorst, Rik Reinking : Fresh Air Smells Funny: an exhibition with selected urban artists. Exhibition catalog. 1st edition. Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 978-3-939583-94-3 .

- Ingo Clauß , Stephen Riolo, Sotirios Bahtsetzis: Urban Art: Works from the Reinking Collection . Exhibition catalog. 1st edition. Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern 2009, ISBN 978-3-7757-2503-3 .

- Claudia Willms: Sprayer in the White Cube. 1st edition. Tectum Verlag Marburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-8288-2473-7 .

- Kai Hendrik Schlusche: StreetArt Basel and Region. The hot spots in the tri-border region. 1st edition. Verlag Gudberg Nerger, Hamburg, 2015, ISBN 978-3-945772-00-3 .

Web links

- Streetartfinder.de - project of the University of Regensburg to capture, localize and categorize street art

- Unurth - Global Street Art Archive (English)

- streetpins.com - International street art community and photo archive

- On the relevance of criminal law

- - in Germany: § 303 and § 304 StGB

- - in Austria: §§ 125, 126 StGB: (online)

- - in Switzerland: Article 144 StGB: Online

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ulrich Blanché: Banksy: Urban art in a material world . Tectum-Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-8288-3541-2 , p. 45 .

- ↑ Ulrich Blanché: Consumption Art - Culture and Commerce at Banksy and Damien Hirst. Bielefeld 2012, ISBN 978-3-8376-2139-6 , pp. 79f.

- ↑ a b Julia Reineke: Street Art. Bielefeld 2007, pp. 13-17.

- ↑ Ulrich Blanché: Banksy: Urban art in a material world . Tectum-Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-8288-3541-2 , p. 44 .

- ↑ Ulrich Blanché: Banksy: Urban art in a material world . Tectum-Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-8288-3541-2 , p. 59-60 .

- ↑ Ulrich Blanché: Banksy: Urban art in a material world . Tectum-Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-8288-3541-2 , p. 101-102 .

- ↑ Heike Derwanz: Street Art Careers. New ways in the art and design market. Bielefeld 2013, ISBN 978-3-8376-2423-6 , pp. 110–121.

- ↑ Malte Göbel: Street Art and Commerce. In: Spiegel online. April 16, 2009.

- ↑ a b Franziska Klün: Street Art and Graffiti - Everything is marketable. ( Memento from August 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) In: Zitty . August 14, 2008.

- ↑ Sony's street art disaster. on: splitbrain.org , March 11, 2007.

- ↑ Hans-Christian Psaar: Street art between recuperation and subversive potential. ( Memento from February 23, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) published in a brochure as part of the Leipzig Kulturdisplace project 2007.

- ↑ Jens Thomas: Subversive and self-glued. In: Katrin Klitzke, Christian Schmidt (Hrsg.): Street Art. Legenden zur Straße. Verlag Archiv der Jugendkulturen eV, 2009, ISBN 978-3-940213-44-0 .

- ↑ Streetart in Germany: A book tops the Facebook page

- ↑ a b This is Banksy

- ^ Social media street art

- ↑ Street art in Istanbul

- ↑ Universal Museum of Arts. Retrieved June 6, 2018 .