Godwit

| Godwit | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Black-tailed godwit in magnificent dress |

||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||

| Limosa limosa | ||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) | ||||||||

| Subspecies | ||||||||

The black godwit ( Limosa limosa ) is a species of bird in the family of the snipe bird (Scolopacidae). Black godwit are long-distance migrants and breed mainly in wet meadows . The species is on the international red list of endangered species as well as on the red list of Germany's breeding birds .

description

measurements and weight

The godwit is a large, elegant wader . It has a body length of 35 to 45 centimeters and reaches a wingspan of up to 75 centimeters. Males weigh 160 to 440 grams, females 244 to 500 grams. Males are usually slightly smaller than females and have a slightly shorter beak.

Appearance

In the magnificent dress , the neck, chest and head are colored orange to deep rust-red, often streaked with white or black spots. The lower abdomen and tail are white, while the chest and stomach are covered with black transverse bands. Their extent is very variable - there are birds with almost no black transverse banding as well as individuals with black stripes from the chest to the under tail. Black godwit moult a variable number of orange-red, gray and black-striped breeding feathers on their mantle and back , which sometimes gives the impression of an incomplete, magnificent dress. The top of the head is dashed in black. The long, straight beak is orange from the base to about halfway in summer, the rest is black. Females are usually a little less intense and less conspicuous in color than males. All year round, black godwit have a white tail with a black end band.

In winter, males and females are colored identically. The coat and wings are then light gray, the chest and belly simply white-gray. The beak is pink with a black tip in a plain dress .

Juvenile birds look like adults in a simple dress, only the top is dark gray-brown, with pale red and yellow-brown feather edges. The throat and chest are pale light brown. In the first summer and autumn, the beak has often not yet reached its full length and is usually completely dark gray.

The black godwit's flight pattern is characterized by the white tail with a black end band, the white stripes on the gray underwings and the long straight beak. Head and beak protrude beyond the body to the front as much as the legs and tail to the rear.

The call sounds like "wed", "Geg" or "grutto". This is why the species has its Dutch name "Grutto". In Germany she is commonly called "Greta" in some regions for the same reason.

Life expectancy

There is evidence of color-ringed godwit, which can be up to 18 years old. Various population-biological studies give values of 20 to 30 percent as the annual mortality of adults. A more recent evaluation of ring finds indicates a possible adult mortality of up to 60 percent per year, but this is not considered likely in specialist circles. The mortality of young animals is significantly higher than that of adults and is estimated at 40 to 70 percent depending on the study.

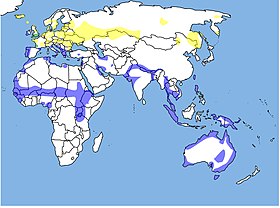

distribution and habitat

The black godwit breeding area extends from Iceland to eastern Siberia . The wintering areas are in Europe , Africa , the Middle East and Australia . The black-tailed godwit breeds mainly on wet meadows and wet pastures in lowlands and coves , but also in raised bogs and fens . In steppe areas they are found in damp, grassy depressions. The animals spend the winter in wetlands. During the migration period, black godwit also rest in mud flats , marshes , mud flats and damp silting zones on the edge of lakes and rivers, estuaries and the Wadden Sea . Black-tailed godwit also overwinter in rice fields and flooded meadows and pastures.

In Germany, the main areas of distribution are in the large grassland areas of the lowlands and along the river marshes of northern Germany and along the coast in the Wadden Sea national parks.

Breeding habitat requirements in Central Europe

The godwit originally bred in moors, coastal marshes and estuaries (see below). Today it breeds in Central Europe mainly on damp to wet, short-grass meadows, which are preferably cultivated extensively. Shallow, water-bearing sinks are supposed to favor settlement. The nest is often made in places that offer some cover, such as bulbs of grass. When rearing chicks, on the other hand, preference is given to vegetation that is not too dense and as rich in flowers as possible, as the young animals find more food there and can move around better.

Subspecies

Three subspecies are differentiated:

- Limosa limosa limosa : The breeding area of the nominate form extends from Western Europe to Central Europe to Central Asia and Russia to the Yenisei River . It winters in Southern Europe, West Africa and the Middle East to the eastern coast of India.

-

L. l. islandica : The Icelandic godwit is smaller than the nominate form, has shorter legs, moults almost completely into breeding plumage in summer and is clearly darker orange-red on the chest. It breeds mainly in Iceland , but is also found in small numbers in the Faroe Islands , Shetlands and Lofoten . It winters in the British Isles as well as in southwest Europe and West Africa. A merger of the Icelandic subspecies with the nominate form is currently being discussed; however, there are still no convincing results of genetic studies.

Icelandic godwit near Lake Mývatn

Icelandic godwit near Lake Mývatn - L. l. melanuroides : The eastern subspecies (Siberian godwit) is even smaller than the Icelandic subspecies and has an even shorter beak. The breeding dress is usually a shade darker and more complete than that of the Icelandic subspecies. The Siberian godwit breed in widely dispersed populations in Mongolia , northern China, and eastern Russia . These birds migrate to India , Indochina , Taiwan , the Philippines , Indonesia , Papua New Guinea, and Australia.

nutrition

The godwit feed on insects , spiders , crustaceans , molluscs and worms . At migration time and in winter quarters, adult black godwit also eat grains of rice if available. Some subpopulations have an almost entirely vegetable diet in winter. Black godwit poke their long beak in the ground, where they locate their prey with the help of the pressure-sensitive beak tip. Sometimes prey animals or parts of plants are also taken up from the surface of the soil; these are localized optically.

The newly hatched chicks look for their own food from day one, so they flee the nest . In the first two weeks they mainly eat small insects up to four millimeters in size that they find in the grass. As soon as the beak is long and firm enough, they too begin to poke at ground arthropods .

Breeding biology

Black godwit usually do not breed until they are three years old, but at the moment there are more and more reports of breeding in two-year-old birds.

Arrivals

In Western Europe, the black godwit's breeding season begins in February / March when they arrive in the breeding area, provided it is no longer freezing there. This is where the couples meet, who often stay together all their lives. In the case of the Icelandic godwit, it was shown that the pairs arrive at the same time, although the partners overwintered several hundred kilometers apart.

Settlement and courtship

Upon arrival, territories are formed, which the male defends with spectacular courtship flights. It flies up steeply, rolls its body around its longitudinal axis and falls down again from a great height. It lets you hear the characteristic "grutto-grutto" call. This part of the courtship is known as the "expressive flight". Other males are aggressively driven from the territory. Both during courtship on the ground and in arguments with other males, the black tail band is presented while walking on the ground.

Black godwit pairs often breed in the same place every year, usually only a few meters away from the old breeding site. Godwit mostly breed semi-colonial, i. H. in smaller groups of 2 to 20 pairs, in densities up to 3 pairs per hectare. But there are occasional single broods. The male creates several nest hollows by pressing his upper body on the ground and turning a hollow in the ground with circular movements. This is often padded with stalks and other plant parts . The female inspects these nest hollows and lays her eggs in the one she has chosen.

Breeding season and enemy defense

The breeding season extends from April to July. A clutch usually consists of four greenish, brown-spotted eggs . In very rare cases three or five eggs are laid. It takes about five days for a godwit to lay four eggs. Both adult birds incubate the eggs for 21 to 24 days until the chicks hatch. During this time, the nest is vehemently defended against enemies by both adult birds. Air enemies such as birds of prey are repelled by aggressive and rapid air attacks, supported by loud calls. Birds from surrounding nests often help with this defense. Even enemies of the ground are repelled from the air; here all adult birds that breed in the area gather in order to fly with dangling legs very low over the predator on the spot. If the vegetation is high enough, the nest is hidden under blades of grass that the breeding bird pulls over it.

Chick rearing

Both parents take care of the chick rearing. The chicks flee the nest and leave the nest a few hours after hatching as soon as they are dry. Then they are led by their parents for up to four weeks until they can fledge. Some families spend these four weeks in the immediate vicinity of the nest, while others wander with their young animals up to three kilometers to areas that offer the young animals more food. Even canals or rivers are crossed, the adults flying and the young ones swimming. In the first three days, the chicks still have to be rowed , this is usually done by the female. The mortality of the chicks in the first week of life is very high and is increased by cold weather conditions. The young animals fledge at 28 to 34 days, and about a week before they can fly several meters.

Migratory behavior

The migratory behavior of birds breeding in Europe is now relatively well known.

Return flight to the wintering areas

After the birds have finished the breeding season, large swarms form on the roosts as early as the second half of May to the end of June. The birds leave their breeding area relatively quickly, at the beginning of July most of the black godwit had already disappeared. The exact timing seems to be linked to the availability of food; in dry summers they leave the breeding areas earlier than in summers with high rainfall.

Ring recoveries indicate a different migration behavior of adults and young animals. In the 1980s, more than 80 percent of the animals shot in France were young. From this it was concluded that the adults fly in a long non-stop flight from the breeding areas or roosts to Spain and Morocco .

Nowadays there is no suitable resting place for the godwit in summer in either France, Spain or Morocco. The construction of dams , changes in agriculture and climate changes have ensured that the areas previously used are now dry in summer and no longer offer any food. Recent observations support the hypothesis that most godwit today fly non-stop directly from their breeding grounds to their wintering areas in West Africa. Only very small numbers, mostly young animals, are still counted in tidal areas along the coasts of Portugal and France. Studies of feed intake and energy consumption have shown that black godwit are physiologically very capable of such a 4500 km flight. This flight would mean about 72 hours of continuous flying. This hypothesis is supported by censuses from the Senegal Delta, where the first birds arrive in the first two weeks of July.

The birds that breed in Germany and the Benelux countries overwinter for the most part in the coastal areas of Senegal , Gambia , Guinea-Bissau and Guinea . The wintering areas here are exclusively in the large river estuaries, the mangrove zone and, above all, the rice-growing areas, the latter being by far the most important. Around 100,000 individuals overwintered in the entire area in winter 2005/2006, around 40 percent of which were found in Guinea-Bissau on the rice fields. Black godwit clearly prefer rice as food in these areas, with the exception of the birds in the Senegal Delta, which feed on animal prey there. Another important wintering area is in Mali near the inner Niger estuary , where a maximum of 40,000 black-tailed godwit winter. The birds found there also mainly ate animal food; however, it is believed that this group of black godwit does not belong to the Western European breeding population and instead breed in Eastern and Central Europe.

Spring migration

Annual birds are significantly underrepresented in Europe. It is still not clear where they will spend their second calendar year. There is absolutely no evidence of black godwit between April and June from Senegal and Guinea-Bissau, but at the same time there are only a few reliable sources for this period. The maximum number of black godwit observed in Mali for the same period is 1000 individuals. Studies of color-ringed birds show that a small number of annuals start breeding in the first year, but the whereabouts of the majority of annuals is still a mystery. These are in the order of 10,000-20,000 individuals.

From the end of December, adult birds fly from their wintering areas in West Africa and Mali directly to the resting areas in Morocco, Portugal and Spain. The resting areas in these countries offer good conditions for feeding at this time of year. In Morocco, the birds arrive in late December to early January - at the same time, a much larger number of birds are also present in Portugal. A comparison of simultaneous counts in both areas suggests that these two groups are separate migration routes, whereby the number of birds in Morocco with around 8,000 individuals is relatively low compared to Portugal / Spain with 40,000 individuals. Simultaneous counts in Portugal and Spain also showed that there is an exchange of birds between the Portuguese roosts and the Spanish ones and therefore both areas are considered to be one large contiguous roosting area given the short distance (270 km). However, there is no direct proof of this by color-ringed individuals. The majority of birds fly non-stop to their breeding grounds from Portugal, Spain and Morocco, and only a very small number still rest in France.

Food ecology during the move

These different resting areas offer the godwit very different food. Godwit feed mainly on grains of rice during winter . In the rest areas in Portugal and Spain, too, rice is the most important food that is available to build up energy reserves for the migration route. In Morocco, France and in the breeding areas, black godwit eat almost exclusively ground-dwelling invertebrates , above all earthworms and mosquito larvae . So you have to change your diet from plant parts to animal food. Studies on other waders have shown that such a change is associated with a reduction in size or, depending on the direction, enlargement of the gizzard and consumes a relatively large amount of energy. This process can take up to a few days. Investigations on the godwit itself showed that even switching from one animal food to another is relatively complicated and is associated with weight loss. It is therefore believed that godwits do not change their diet several times during the spring migration. It is much more likely that there are two groups of birds with different migratory behavior.

The first of these groups maximizes the feeding time of plants and then flies directly from Guinea-Bissau and the neighboring countries to Portugal / Spain, and from there non-stop to the breeding areas in the Benelux and Germany. The second group - very likely much smaller in number - is more likely to switch to animal food, possibly already in Senegal. From there they fly to Morocco, then to France and from there to the breeding areas.

Another possibility is that an even smaller number of black godwit winters in Mali and from there, possibly with a short stopover in Tunisia, moves to Italy in order to fly from there to the breeding areas. However, it is assumed that the majority of the godwit that rest in Italy breed in Central Europe and that the number of animals breeding in Germany or in the Benelux that use this migration route is very low.

Stock size and development

The original breeding habitat of the godwit are fens and river estuaries . These natural habitats have decreased more and more as a result of human interference. At the same time, however, through the establishment of what we see today as extensive meadow and pasture farming, large-scale new breeding areas were created, which enabled the godwit to colonize the cultural landscape. In northern Germany, but especially in the Netherlands, large-scale embankments have also created new breeding areas, which led to a significant increase in the population. Since the early 1960s, the consequences of structural change in modern agriculture have had a negative impact; The land consolidation and intensification of agriculture led to large-scale conversion of meadows and pastures into arable land and intensively cultivated pastures. These areas were abandoned by the black godwit, as a result of which the black godwit population decreased and continues to decline rapidly in Western Europe. In Germany (2005: 4700) there were still around 6600 breeding pairs in 1999, around 4500 of them in Lower Saxony. The godwit has the status “critically endangered” (category 1) on the German red list.

Worldwide inventory trend

Due to the different migration routes (“flyways”), the population of the nominate form ( Limosa l. Limosa ) can be divided into two sub-populations: a Western European and a Central European-Asian. The western population breeds in Scandinavia , Germany , Switzerland , Benelux and France and winters in southwest Europe and West Africa (see above). It consists of around 60,000 breeding pairs. The Central European-Asian population breeds from Poland to the Yenisei and overwinters in the Middle East and India. This population is estimated to be around 30-57,000 breeding pairs. Although the black godwit is increasing in some countries, the majority of the population is also declining here, especially in Russia and Belarus - both countries together house 24 - 40,000 breeding pairs. The population of the Icelandic subspecies is increasing; however, it represents only a small part of the world population. For the eastern subspecies one can only make assumptions based on the number in Australian winter quarters. This is also decreasing rapidly. According to estimates, there are still 634,000 to 805,000 breeding pairs worldwide (as of August 2006).

Worldwide the black godwit population has decreased by almost 30 percent over the past 15 years. Therefore, the godwit was upgraded to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2005 ; now this species is internationally regarded as "near threatened" (warning list). In the Netherlands, where an estimated 90 percent of Western European godwit breed, the population has declined by more than half over the past decade.

Inventory forecast

The godwit, like most snipe birds, is one of the species that will be particularly affected by climate change. A research team that, on behalf of the British environmental authority and the RSPB, examined the future development of the distribution of European breeding birds on the basis of climate models, assumes that the range will decrease significantly by the end of the 21st century and move further north. Around eighty percent of today's range will no longer offer the species suitable habitats. Finland and northern Russia are considered to be potential new breeding areas. According to these population forecasts, the black-tailed godwit will be preserved as a Central European breeding bird, but its range is significantly smaller than it is today. It will disappear especially in Eastern Central Europe.

Reasons for the negative inventory development

The insufficient breeding success is considered to be the most important reason for the sharp decline in populations. The increasing intensification of agriculture and the associated loss of habitat are named here as the most important reasons. Many meadows and pastures are being converted into arable land on which godwit can no longer breed. Intensive farmed pastures are often not settled or abandoned nest losses due to cattle occurs are at high livestock density high. The always earlier mowing date dramatically and directly reduces the survival probability of even less mobile, young chicks, as they are simply mowed over. Even late nests naturally have almost no chance of hatching due to early mowing. A relatively early mowing also has a negative impact on the food supply for the young animals, as there are fewer insects and less protection from predators in short grass. This in turn has a large and direct influence on the chances of survival of the young animals. In the county of Bentheim and Emsland, in the long years godwits were represented numerous stocks have declined sharply through the upheaval of meadows and pastures for the cultivation of maize, which is after the currently strong here boom since the late 1980s, biogas plants and has tightened large fattening houses . Furthermore, increasing predation pressure from birds of prey, ravens , gulls and herons , but especially from nocturnal mammals, is named as the reason for the decline in populations. After rabies has been successfully combated in Germany over the past twenty years, the population of foxes has increased significantly. According to recent studies, the fox is the main predator in several meadow bird areas in Germany and the Netherlands.

Hunting by humans in Europe only takes place in France, the only European country where black godwit hunt is still allowed. There are estimates that around 20,000 to 30,000 black-tailed godwit are shot down during bird migration in France each year.

Conservation measures

Many Western European countries have started projects to protect the godwit, placed breeding areas under protection and adjusted the management of the areas. However, the results are only partially successful. An EU action plan is currently (August 2006) being worked on. In order to save the godwit from extinction, Bird Life International recommends that the existing breeding habitats in the entire range of the godwit should be placed under special protection. A very late mowing date, not before the end of June, is of great importance, as is a low livestock density, little or no mineral fertilization and possibly a rise in the groundwater level. At the same time, the rest areas during migration and the winter areas must be appropriately protected. Black godwit hunting should be banned.

Godwit and human

Since the beginning of the last century the godwit has inhabited areas that humans work, in Western Europe the godwit can be called a cultural follower . The black-tailed godwit, together with the lapwing , was a character bird of the damp meadows and pastures until the 1980s. In the Netherlands the godwit is still one of the most common breeding birds in the ubiquitous meadows and pastures, so that it is almost treated as a national bird there. The black godwit eggs, together with lapwing eggs, were also an important source of food for the rural population in Germany, especially in the immediate post-war period.

Sources and further information

Individual evidence

- ↑ AJ Beintema, O. Moedt, D. Ellinger: Ecological Atlas van de Nederlandse weidevogels . Schuyt & Co, Haarlem 1995, ISBN 90-6097-391-7 .

- ↑ a b c Limosa limosa in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2011. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed November 13, 2011th

- ↑ Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliott, Jordi Sargatal (eds.): Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 3: Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions, 1996, ISBN 84-87334-20-2 .

- ^ J. Melter: Stock situation of the meadow limes in Lower Saxony. In: T. Krüger, P. Südbeck (Ed.): Wiesenvogelschutz in Niedersachsen. Nature conservation and landscape management in Lower Saxony, 2004.

- ↑ Christoph Grüneberg, Hans-Günther Bauer, Heiko Haupt, Ommo Hüppop, Torsten Ryslavy, Peter Südbeck: Red List of Germany's Breeding Birds , 5 version . In: German Council for Bird Protection (Hrsg.): Reports on bird protection . tape 52 , November 30, 2015.

- ^ Thorup O. (comp) 2006: Breeding Waders in Europe 2000. International Wader Studies 14. Wader Study Group, UK.

- ^ Brian Huntley, Rhys E. Green, Yvonne C. Collingham, Stephen G. Willis: A Climatic Atlas of European Breeding Birds. Durham University, The RSPB and Lynx Editions, Barcelona 2007, ISBN 978-84-96553-14-9 , p. 191.

- ↑ "WSG" annual conference 2006, Falsterbo, Sweden ( Memento of the original from November 1, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

literature

- AJ Beintema, O. Moedt, D. Ellinger: Ecological Atlas van de Nederlandse weidevogels. Schuyt & Co, Haarlem 1995, ISBN 90-6097-391-7 .

- Josep del Hoyo , Andrew Elliott, Jordi Sargatal (eds.): Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 3: Hoatzin to Auks. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 1996, ISBN 84-87334-20-2 .

- JA Gill, K. Norris, PM Potts, TG Gunnarsson, PW Atkinson, WJ Sutherland: The buffer effect and large-scale population regulation in migratory birds. In: Nature. 412 (6845), 2001, pp. 436-438.

- T. Krüger, P. Südbeck (ed.): Wiesenvogelschutz in Niedersachsen. (Nature conservation and landscape management in Lower Saxony, Volume 41). Lower Saxony State Office for Ecology, 2004.

- DPJ Kuijper, E. Wymenga, J. van den Kamp, D. Tanger: Wintering areas and spring migration of the Black-tailed Godwit. Bottelnecks and protection along the migration route. (Altenburg & Wymenga Ecologische Onderzoek rapport 820). Veenwouden 2006. (online at: altwym.nl) (PDF; 6.4 MB)

- Erhard Nerger, Helmut Lensing: The godwit (Limosa limosa) - a snipe bird that is endangered not only in the Emsland and the county of Bentheim. In: Study Society for Emsland Regional History (Ed.): Emsland History. Volume 19, Haselünne 2012, ISBN 978-3-9814041-3-5 , pp. 22-53.

Web links

- Limosa limosa in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2011. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed November 13, 2011th

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Limosa limosa in the Internet Bird Collection

- Meadow bird protection Protection program for black godwit in the Emsland

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 0.9 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (Eng.)