People's Militia (China)

The Chinese People's Militia ( Chinese 中国 民兵 , Pinyin Zhōngguó Mínbīng ) is one of the three pillars of the armed forces of the People's Republic of China. Like the People's Liberation Army and the People's Armed Police , it is under the command of the Central Military Commission of the People's Republic of China .

Imperial times

Historically, the People's Militia, also called 民兵 at that time, first appeared in the year 930, during the Later Tang Dynasty , when men from the rural population were recruited to occupy the beacon stations on Shu Road from Jianmen Pass to the north. They had to cut their long hair and were tattooed on their faces like convicts. With a 1069 came into force reform of Wang Anshi , Deputy State Council at the imperial court of the Song Dynasty , was the county officials the obligation transferred to organize part-time homeland security squads that the Imperial Army (禁军, Pinyin Jinjun ) and the Prefecture troops (厢 兵, Pinyin Xiāngbīng ) in the fight against the Kitan , Jurchen and Mongols . Ten neighboring households were grouped together in a so-called “group of ten” (甲, Pinyin Jiǎ ), the head of which (甲 头, Pinyin Jiǎtóu ) was responsible for collecting taxes. 10 groups of ten formed a "home security group" (保, Pinyin Bǎo ) from which men of military age were called to serve in the militia if necessary. The Song-era people's militia was better trained and enjoyed a much higher reputation than the force-recruited militiamen of the Later Tang. An archery division from a local militia performed honorary service in the imperial palace in constant change. In the Ministry of War (兵部, Pinyin Bīngbù ) there was a separate People's Militia Department (民兵 卫 案, Pinyin Mínbīng Wèiàn ), which together with the People's Militia Working Group (民兵 房, Pinyin Mínbīng Fáng ) in the Office for Military Affairs (枢密院, Pinyin Shūmì Yuàn ) controlled and monitored the operations of homeland security troops. In the end, however, in view of the numerical superiority of the opponents, even the best organization did not help: in 1127 northern China had to be evacuated to the Huai He line, and in 1279 Kublai Khan had conquered all of China.

The Mongolian Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) was an occupation regime that employed Central Asian mercenaries (the ancestors of today's " Hui Chinese "), but had no use for homeland security groups formed from locals . With the takeover of power by Zhu Yuanzhang and the establishment of the Ming Dynasty , a period of almost 100 years of peace began and there was no reason to reactivate the people's militia. However , the situation changed in the middle of the 15th century, during the Zhengtong reign (1436–1449). Along the entire northern border, over a length of 5000 km, the Mongols invaded again, so that four new garrison towns had to be built there (which did not prevent Altan Khan from besieging Beijing in 1550). At the same time, the activity of the Japanese bandit gangs (倭寇, Pinyin Wōkòu), which had ravaged the coastal provinces at the beginning of the Ming dynasty, reached a new high point. As on the northern border, the main problem here was the sheer length of the coastline to be defended : from Hainan 2500 km to Fujian , then 1000 km to Zhejiang and another 1900 km to Shandong , from there 3200 km to the Yalu estuary on the border Korea. The Japanese bandits were very well organized, carried out their raids with great speed and had mostly disappeared again before the government troops arrived. Therefore, Wang Yangming , Secretary of the War Ministry (兵部 主事, Pinyin Bīngbù Zhǔshì ), reintroduced the Song-temporal Baojia system shortly before his release in late 1506 .

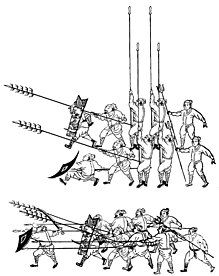

Wang Yangming, also known by his maiden name Wang Shouren, who had already dealt with the matter during his time as an intern (观 政, Pinyin Guānzhèng ) in the Ministry of Commerce and Public Buildings (工部, Pinyin Gōngbù ) and had written eight related enthrones , took over Wang Anshi's organizational structure unchanged, i.e. with 10 groups of ten that formed a homeland security group. The militia officers themselves were no longer called 民兵 (Pinyin Mínbīng ), ie “soldiers from the people”, but 民 壮 (Pinyin Mínzhuàng ), “strong fellows from the people”. Even during the Zhengtong crisis, there were a few volunteers who volunteered for the militia. For example, 4,200 civilians in Shaanxi Province helped defend the northern border. Now, however, the militia service was placed on a regular basis - which had already been discussed since then: every able-bodied farmer (the urban population was exempt from militia service) could devote himself to field work for 9 months a year, then - usually during the dry season in winter - he had to work for to move to the nearest garrison town for three months to undergo or refresh military training. At first these militiamen were not particularly efficient. Especially on the east coast, where they were confronted with former professional soldiers , absolute masters of saber fencing , they often fled when the enemy approached, some of whom were advancing with contingents of up to 4,000 men. Only when General Qi Jiguang had formed a special force to fight the Japanese, the so-called "Qi tigers" (戚 虎, Pinyin Qī Hǔ ), which he drilled in the combined use of short and long weapons, i.e. saber and lance, succeeded it was in 1563 to finally drive out the bandits.

The Manchurian Qing dynasty (1644-1911) was, like the Yuan dynasty, an occupation regime. Unlike the Mongols, however, the Manchus allowed Chinese collaborators to do military service in the Green Standard immediately after they came to power . Shortly afterwards, the Baojia system was reactivated, albeit with slight changes: the basic unit of 10 neighboring households was now called “Wohngruppe” (牌, Pinyin Pái ). 10 residential groups, i.e. 100 households, formed a "group of ten" (甲, Pinyin Jiǎ ), and 10 groups of ten, i.e. 1000 households, formed a "home protection group" (保, Pinyin Bǎo ). Each district administrator (知县, Pinyin Zhīxiàn ) had to recruit a militia company of 50 men from the homeland security groups. These men wore a uniform on which xx 縣 民 壯, ie “militia of the district xx”, was noted in large letters. The people's militia now had a significantly lower status than during the Ming dynasty and had become a kind of auxiliary police; the military tasks were largely taken over by regular troops. For comparison: in Qingpu County (now Shanghai ) a total of 340 militiamen were stationed at two bases during the Wanli government (1573–1620), but there were no barracks for the regular troops. During the reigns of Qianlong and Jiaqing (1736-1820) there were just 50 militiamen, but 2000 men in the regular army.

republic

After the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, some of the imperial troops were taken over (the National Revolutionary Army was not established until 1925), but the People's Militia was disbanded. Starting in May 1914, the "Security Force" took over their duties as auxiliary police. Initially called 保卫 团 (Pinyin Bǎowèituán ), the organizational structure more or less corresponded to the Qing-dated Baojia system: 10 households formed a residential group, 10 residential groups a group of ten, and 5 groups of ten a home protection group. A man from each household was to be sent to the security force, and the district administration then formed a regiment from this, which was financially supported by the local landowners and wealthy merchants. These were initially only “guidelines for local security troops ” (地方 保卫 团 条例, Pinyin Dìfāng Bǎowèituán Tiáolì ) issued by the Beiyang government , which were passed in July 1929 by the National Government of the Republic of China in Nanjing, which is now considered legitimate, with the “Law on the security troops of the districts ”(县 保卫 团 法, Pinyin Xiàn Bǎowèituán Fǎ ) were placed on a legally correct basis. Now every street (闾, Pinyin lǘ ) was referred to as a “residential group”, every community or large community as a “group of ten”, and every district as a “main squad ” (总 团, Pinyin Zǒngtuán ). All men between the ages of 20 and 40 had to undergo military training there, then returned to their hometowns to pursue their normal work. If security problems arose, they were alerted and had to report to their unit immediately.

On June 17, 1932, the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of China issued a decree stipulating a uniform flag for the district security troops, with the Republican sun on a white background and a 9 cm wide red stripe on the edge facing the flagpole, on the top to bottom the number of the main squad, the group of ten and the residential group was noted. In December 1936 this unification process was with the Cabinet adopted "Regulations on the establishment of Homeland Security bars in every province and in every administrative region " (各省区保安司令部组织规程, Pinyin Gè Sheng Qū Bǎo'ān Sīlìngbù Zǔzhī Guicheng ) its conclusion. The security troops of the districts and all other resident groups that had formed all over the country were added to the reserve , with a regiment in each district, again headed by the district administrator. This security force was now called 保安 团 (Pinyin Bǎo'āntuán ) - the semantic difference to 保卫 团 is minimal - and housed together with the regular military in barracks.

When the military units of the Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang theoretically united against the Japanese occupation forces in 1937–1945 , but often fought with one another, the CCP formed guerrilla units from the local population in the areas only partially controlled by the Japanese military who, detached from the official command structure, used pinprick tactics to exert constant pressure on the occupation troops and liberate entire regions. At the end of the war, in addition to 1.3 million full-time soldiers, more than 2.6 million civilians were organized in these militias, armed with weapons mainly captured by the Japanese. A total of 90 million people lived in the liberated areas around the militia bases.

As an example of the countless guerrilla troops that operated at that time, the 3rd section of the partisan column Wusong - Shanghai (淞沪 游击 纵队 第三 支队, Pinyin Sōng Hù Yóujī Dìsān Zhīduì ) is mentioned. This unit was founded after Shanghai fell on November 9, 1937, by two CCP members and four old cadres of the peasant movement (a joint venture between the Kuomintang and the CCP 1923–1926) in January 1938 under the name "Anti-Japanese People's Self-Protection Group " (人民 抗日 自卫队, Pinyin Rénmín Kàngrì Zìwèiduì ) in Qingpu . The membership grew, and the name was changed to "Standing Troop" (常备 队, Pinyin Chángbèi Duì ), which was now run directly by the CCP's Qingpu County Association's Working Committee (工作 委员会, Pinyin Gōngzuò Wěiyuánhuì ). In 1939 the standing troops were finally integrated into the Wusong – Shanghai partisan column as the 3rd division. It now had 3 brigades, each with 2 or 3 companies of 50 men each, a total of more than 400 men. The 3rd Division had more than 500 rifles, 30 light machine guns and a special pistol squad of a good 40 men.

Formally, these partisan troops were armed gangs, like today's rebel militias in developing countries - the official militia of the Republic of China was still the Kuomintang security force. On the other hand, the CCP had built state-like structures since 1925, including a "Central Revolutionary Military Commission" (中央 革命 军事 委员会, Pinyin Zhōngyāng Gémìng Jūnshì Wěiyuánhuì ), which Mao Zedong had chaired since December 1936 . This was the high command of the Red Army (renamed the “ People's Liberation Army ” after the victory over Japan ) and the de facto Ministry of Defense for the liberated areas. The military commission was also at the head of the chain of command of the various partisan units. The Second Chinese Civil War (1945–1949) was mainly fought by the People's Liberation Army in large-scale field battles, while the CCP militias in the so-called "partisan areas" (Pin, Pinyin Yóujīqū ) on the border between liberated and Kuomintang-held land propaganda- and took over transport tasks. In these rural areas, the militias made an important contribution to the liberation of China, while in the cities - 586 cities in the hands of the CCP in mid-1948 - they became a problem. In rural areas, particularly in northern China, the expropriation of the landowners has been a declared goal of the CCP. In the cities, on the other hand, the capitalists had to be protected from radical excesses so that they could contribute to the reconstruction of the country with their economic strength. After initial difficulties, from 1947 onwards the CCP leadership increasingly managed to bring the misguided enthusiasm of the grassroots under control.

People's Republic

After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the People's Militia was initially used to rebuild the country - the first thing that had to be repaired was the more than 50% destroyed railway network - and also to maintain security and order in the country. In June 1950, 400,000 released Kuomintang soldiers had still not returned to their hometowns. These men, who had often spent their entire professional life in the military, often formed criminal gangs, many of whom were still in contact with the high command in Taiwan and sometimes also committed acts of sabotage. The People's Militia itself was integrated into a regulated system in connection with the tensions on the Korean peninsula . The Central Military Commission had already been elevated to the status of a constitutional body with the "Joint Program of the Political Consultative Conference of the Chinese People", a kind of interim constitution, which was passed by the Political Consultative Conference of the Chinese People in September 1949. In June 1950, a “People's Armament Department” (人民 武装部, Pinyin Rénmín Wǔzhuāngbù ) was created at the Central Military Commission , which was responsible for recruiting, organizing and training the people's militia. This department set up branches in every district and in every independent city , which assigned all men between 18 and 35 years of age who were not already serving in the People's Liberation Army to a people's militia unit. In addition to their regular employment, the militia cadres had to complete a 30-day training course that they had to complete within a year, while the ordinary militia officers did a 15-day basic training course in one piece.

At first, all of these were just official instructions. It was not until March 23, 1953, when Mao Zedong, as chairman of the Central Military Commission, signed the order to set up a working group to draft a law on military service. After numerous discussions, including the question of converting from a volunteer army to a conscription system, the first National People's Congress finally passed the "Conscription Law of the People's Republic of China" in its second session on July 30, 1955 (中华人民共和国 兵役法, Pinyin Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó Bīngyìfǎ ) adopted. Article 58 deals with the people's militia, which continued to be responsible for public safety and the protection of the means of production. The implementing regulations stipulated that the People's Armament Department set up offices not only at the district level, but also at the community level, i.e. in large communities , communities and street districts . Militia units were now set up not only in every community, but also in every mine and in every major company. If necessary, women over the age of 18 and men over 35 could now also be called in to serve in the militia. In principle, there were now two categories of militia officers: the so-called "basic militia" (基干 民兵, Pinyin Jīgàn Mínbīng ), ie the members of the core force of the people's militia, and the "common militia" (普通 民兵, Pinyin Pǔtōng Mínbīng ). The basic militia should mainly be assigned to former members of the People's Liberation Army under the age of 28, and women could only serve in separate women's sections of the basic militia. All other men between 18 and 35 were assigned to the common militia.

The overall strength of the people's militia and the intensity of the training varied depending on the threat situation and political line. In May 1957, for example, the USA had signed an agreement with Taiwan to station MGM-1 Matador cruise missiles at the Tainan Air Force Base , which could reach targets deep in China. The first cruise missiles equipped with conventional warheads arrived in Taiwan in May; from November 1957 the Matador were equipped with W5 nuclear warheads. Under the influence of these events, the Central Military Commission held a large conference from May 27 to July 22, 1958, attended by Mao Zedong, Defense Minister Peng Dehuai and the other permanent members, more than 1,000 high-ranking officers. The theme of the conference was how to modernize China's military while still keeping the spirit of battle time. Peng was for modernization and closer cooperation with the Soviet Union, Mao for a return to the grassroots roots of the people's war. The majority of the conference participants supported Mao, and it was decided to further expand the militia under the slogan "Everyone is a soldier".

Relations with the Soviet Union were already tense at this point. Then from August 23, 1958, Mao had the Kinmen Islands off the coast of Fujian Province , which were held by Taiwan, bombarded with artillery and rockets without informing the Soviet Union beforehand. From the reluctant reactions of the Soviet Union, the Chinese government concluded that they could not rely on their allies in the event of a conflict with Taiwan's protective power, the USA. As a result, the decision of the ZMK conference of July to expand the people's militia was implemented more quickly. In January 1959 the militia had grown to 220 million men. For comparison: at the end of 1958 the People's Republic of China had a total of 653 million inhabitants. This means that all of the strong young men and women were actually in the militia, i.e. precisely the population group that produced most of the Chinese grain on the looser terraces of the north and the rice fields of the south, where machine cultivation was not possible. The problem here was that parallel to the increase in personnel in the People's Militia, training was also intensified, with daily drill, bayonet fencing, etc.Together with other imprudent decisions such as setting unrealistic production targets for iron and steel to be produced in small blast furnaces in every village, this led to this that the peasants in the people's communes were too exhausted to devote themselves to farm work. The autumn harvest of 1958 could only be partially brought in. In combination with droughts and floods in the following years, a famine developed in which around 20 million people were killed by 1961.

It was to be seen early on that the great leap forward would not go as planned. At a four-week Politburo meeting in July 1959, Defense Minister Peng Dehuai, who was concerned about the operational capability of the People's Liberation Army in view of the food shortage, voiced severe criticism. Mao admitted he had made a mistake with the ambitious steel project, but then made sure that the Central Committee dismissed Peng as defense minister in August under the pretext of collaboration with the Soviet Union. Lin Biao was appointed his successor on September 17, 1959 . Like Mao, Lin was a supporter of the People's War, but above all a very successful general. It was clear that the people's militia, armed with the Assault Rifle 56 , could do little against the American-Taiwanese nuclear missiles, even with their impressive number of 220 million men and women. Therefore, he reduced the team strength and switched from blind drill to more in-depth training. Now every people's commune , ie what was called a “ community ” (乡) before 1958 and after 1978 , had a militia company (连, Pinyin lián ) with around 200 men, a district accordingly had around 10 companies. With around 2500 administrative units at the district level, this results in a total of around 5 million men and women.

The personnel changes at management level during the Cultural Revolution - in 1971 there was a rift between Lin Biao and Mao Zedong, the new defense minister from 1975 onwards was Ye Jianying , then from 1978 onwards Xu Xiangqian - had little effect on the practical training of the people's militia. Then in 1979 there was a brief but violent exchange of blows with Vietnam . In addition to 200,000 soldiers from the People's Liberation Army from Guangxi and Yunnan , several thousand members of the People's Militia from these provinces took part in the conflict as so-called "Front Support Militia" (支前 民兵, Pinyin Zhīqián Mínbīng ). Their task was to carry ammunition and food into the front trenches and to get the wounded out of the fire zone and bring them to the nearest field hospital. These militiamen were poorly equipped. Although they all had an identification tag, some of them wore civilian clothing and were therefore difficult to distinguish from the Vietnamese militia for the regular soldiers, especially since they often came from the Zhuang ethnic group, spoke their own language and outwardly looked like Vietnamese. In addition, as in the Second Civil War, the militia lacked discipline. For example, the Bahe Township Militia Company from Tiandeng County decided on its own initiative on February 25th to occupy Elevation No. 4. The 205 militiamen succeeded in completely destroying the Vietnamese unit at this height, and so on September 17, 1979, the Central Military Commission awarded them the honorary title of "model company" (支前 模范 民兵 连). Nonetheless, this was ultimately military disobedience. According to calculations by the logistics department of the Kunming military district , during the fighting between February 17 and March 16, 1979, i.e. within four weeks, 6,954 soldiers and militiamen were killed, more than 14,800 men were wounded, other estimates put 26,000 dead and 37,000 Wounded out.

It was clear that the Chinese military was in dire need of reform. For example, the reintroduction of epaulettes with insignia in dress uniforms or collar tabs in field suits should make the chain of command more clearly visible. On December 4, 1982, the National People's Congress passed a new constitution in which Article 93 introduced an additional "Central Military Commission of the People's Republic of China" (中华人民共和国 中央 军事 委员会, Pinyin Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó Zhōngyāng Jūnshì Wěiyuánhuì ) parallel to the Party's Central Military Commission has been. The division of powers between the two military commissions was not further elaborated there, and since Deng Xiaoping they have always been led in personal union, but since the term of office of the State Military Commission corresponds to that of the National People's Congress and this is responsible to the People's Congress, a certain parliamentary control is guaranteed here . On May 31, 1984, the National People's Congress enacted a new conscription law, valid from October 1, 1984, where the tasks of the militia were more precisely defined in Article 36:

- Practice service as preparation for the event of war

- Border Guard

- Maintaining public safety

In the "Guidelines for Militia Work" (民兵 工作 条例, Pinyin Mínbīng Gōngzuò Tiáolì ) of the State Council and the State Military Commission of December 24, 1990, valid from January 1, 1991, further details were set out in Article 11:

- In the country, companies or battalions of the people's militia are to be set up with the administrative village as the smallest unit

- In the cities, trains, companies, battalions and regiments of the people's militia are to be set up with the operations, public facilities or the street district as the smallest unit

- Technical troop departments are to be set up in the units of the basic militia in accordance with the requirements in preparation for the event of war and the equipment available

- Air defense battalions and regiments must be set up at important civil defense facilities in cities, traffic junctions and other objects worthy of protection

- The technical troop divisions can be spread over several units

Articles 22 to 24 deal with training:

- People's militia training centers are to be set up step by step in the districts

- The printed teaching material is to be made available by the General Staff of the People's Liberation Army, exercise equipment, ammunition, etc. by the military district of the respective province as well as the branch of the Department for People's Armament in the district

- The militia officers are compensated for the loss of earnings during the exercises, farmers from the local government , workers and employees in the cities from their employer

These guidelines are in principle still valid today, only the Department for People's Armament at the Central Military Commission was transformed into the “National People's Mobilization Commission” (国家 国防 动员 委员会, Pinyin Guójiā Guófáng Dòngyuán Wěiyuánhuì ) on November 29, 1994 , which is subordinate to the State Council ; Up until now, the commission's chairman has always been the prime minister. The People's Mobilization Commission has branch offices in each district and, in addition to recruiting and training, is primarily concerned with air defense and securing transport links through the militia. At the Central Military Commission there is still a "Department for People's Mobilization" (中央军委 国防 动员 部, Pinyin Zhōngyāng Jūnwěi Guófáng Dòngyuánbù ), which has bundled border protection competencies since the military reform that came into force on January 1, 2016. The Department of popular mobilization is authorized to issue instructions to the popular mobilization Commission towards, the head office of the People's Mobilization Commission (国家国防动员委员会综合办公室, Pinyin Guojia Guofang Dongyuan Wěiyuánhuì Zonghe Bàngōngshì ) is in the office of the Department of popular mobilization in the VBA building (八一大楼, Pinyin Bā Yi Dàlóu ), 7 Fuxing Street , Beijing .

During the COVID-19 pandemic , militiamen from all over Hubei were deployed to measure fever on the arteries.

Web links

- Official Website of the National People's Mobilization Commission (Chinese)

- Online edition of the magazine 《中國 民兵》 / "Chinese People's Militia" (Chinese)

- Online edition of the 《解放军报》 / "People's Liberation Army Newspaper" (Chinese)

- Online edition of the 《解放军报》 / "People's Liberation Army Newspaper" (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ White Paper of the Armed Forces of the People's Republic of China. In: http://german.china.org.cn/ . Retrieved October 28, 2018 . For the different military commissions of state and party see the section "People's Republic".

- ↑ 罗 竹 风 (主编): 汉语大词典.第六卷. 汉语大词典 出版社, 上海 1994 (第二 次 印刷), p. 1423.

- ^ Charles O. Hucker: A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford University Press , Stanford 1985, pp. 166, 232 and 332.

- ^ A b Charles O. Hucker: A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford University Press , Stanford 1985, p. 367.

- ^ The Military Affairs Bureau was responsible for tactics and individual operations, the War Department for overall strategy and resource allocation. Charles O. Hucker: A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford University Press , Stanford 1985, pp. 332 and 436.

- ↑ Kai Filipiak: The Chinese Martial Art - Mirror and Element of Traditional Chinese Culture. Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2001, pp. 42–44.

- ↑ This had partly ideological reasons - in Confucianism the merchants are at the bottom of the social order, like the Jews in Europe once - but mainly practical reasons: the wooden shaft lance used by the military of the Ming period was 5.44 m long and weighed 4.13 kg; it took considerable strength and endurance to wield this weapon in controlled movements for long periods of time (see Filipiak, pp. 165 and 177–179). A detailed explanation of why farmers were better soldiers can be found in 戚繼光 : 紀 效 新書.華聯 出版社 , 台北 1983, p. 19f (German by Filipiak, p. 160).

- ↑ 罗 竹 风 (主编): 汉语大词典.第六卷. 汉语大词典 出版社, 上海 1994 (第二 次 印刷), p. 1424.

- ↑ Kai Filipiak: The Chinese Martial Art - Mirror and Element of Traditional Chinese Culture. Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig 2001, pp. 45–47 and 149.

- ^ Charles O. Hucker: A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford University Press , Stanford 1985, pp. 332 and 367.

- ↑ 罗 竹 风 (主编): 汉语大词典.第六卷. 汉语大词典 出版社, 上海 1994 (第二 次 印刷), p. 1424.

- ↑ 上海市 地 方志 办公室, 区 县志, 县志, 青浦 县志. In: shtong.gov.cn. April 16, 2002, Retrieved October 19, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ 《地方 保卫 团 条例》. In: 《东方 杂志》 1914 年 5 月 20 日 , 第十一 卷 第一 号.

- ↑ 林 尹 , 高明 (主编): 中文 大 辭典.第一 册. 中國 文化 大學 出版 部, 台北 1971 (九 版), p. 1030.

- ↑ Note: it was the Ministry of the Interior and not the Ministry of War that issued this decree. The security force was still seen as auxiliary police at the time.

- ↑ 湖南省 保安 司令部. In: http://sdaj.hunan.gov.cn . Retrieved October 20, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ 上海市 地 方志 办公室, 区 县志, 县志, 青浦 县志, 第二十 一篇 军事. In: shtong.gov.cn. April 16, 2002, accessed October 21, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ Stephen Uhalley Jr .: A History of the Chinese Communist Party. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford 1988, pp. 74 and 77.

- ↑ Stephen Uhalley Jr .: A History of the Chinese Communist Party. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford 1988, pp. 81 and 96.

- ↑ 中华人民共和国 兵役法. In: http://www.npc.gov.cn/ . July 30, 1955, accessed October 24, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ Stephen Uhalley Jr .: A History of the Chinese Communist Party. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford 1988, pp. 116-120.

- ↑ http://www.chinatoday.com/data/china.population.htm

- ↑ Stephen Uhalley Jr .: A History of the Chinese Communist Party. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford 1988, p. 121.

- ↑ Stephen Uhalley Jr .: A History of the Chinese Communist Party. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford 1988, pp. 123-125.

- ↑ From 1983 onwards, more modern and lighter versions such as the assault rifle 81 , then from 2006 the assault rifle 03 were gradually converted, but some militia units still use the old replica of the AK-47 .

- ↑ 请 尊崇 我们 的 民兵 英模. In: http://www.81.cn/ . January 3, 2018, accessed October 27, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/statisticaldata/yearlydata/YB1999e/a01e.htm

- ↑ Here is an example of how Vietnamese agents took advantage of this circumstance to wreak havoc in a militia unit from Tianyang County : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZHmAv0wmP4

- ↑ King C. Chen: China's War with Vietnam, 1979. Issues, Decisions, and Implications. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford 1987, p. 114.

- ↑ 中华人民共和国 宪法 (1982 年). In: http://www.npc.gov.cn/ . December 4, 1982, Retrieved October 28, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ Constitution of the People's Republic of China. In: http://www.verfassungen.net . December 4, 1982. Retrieved October 28, 2018 .

- ↑ Stephen Uhalley Jr .: A History of the Chinese Communist Party. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford 1988, pp. 207f.

- ↑ 中华人民共和国 兵役法 (1984 年). In: http://www.npc.gov.cn/ . May 31, 1984. Retrieved October 28, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ 民兵 工作 条例. In: http://www.mod.gov.cn/ . August 27, 2009, Retrieved October 28, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ 国务院 、 中央军委 关于 成立 国家 国防 动员 委员会 的 通知. In: http://www.mod.gov.cn . November 29, 1994, Retrieved November 12, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ 国家 国防 动员 委员会. In: http://www.gfdy.gov.cn . August 8, 2013, accessed November 12, 2018 (Chinese).

- ↑ Corona virus is spreading: Beijing cancels New Year celebrations. In: tagesschau.de. January 23, 2020, accessed January 23, 2020 .