Mural print

Mural print , often also called wall decoration , is the folklore name for a graphic sheet that was used to decorate rooms and was usually framed under glass . The period from 1840 to 1940 was the most important epoch of mural printing, as the development of the works here was determined by new printing techniques, the expansion of the transport network enabled widespread sales and - compared to previous centuries - the greater prosperity in art in one's own home came up.

Mural prints were mostly made from works by contemporary painters who were selected by art publishers for their popular motifs and some of whom had specialized in the reproductive graphics sector. The original image was not used as the starting point for the reproductions, but a template prepared as an intermediate step.

There was no universal contemporary term for wall picture prints. The most common words "room decorations" and "Zimmerzierde" which, however, also other wall decorations were like wall brackets - Nippes included. Publishers and dealers used the general and neutral term "Kunstblatt". Today's antique trade classifies mural prints as decorative graphics. Even if the antique trade and flea markets make eye-catching motifs such as fairies and heathland sometimes appear as the epitome of mural printing, the actual range of topics was much wider.

history

Before 1860

In the decades before 1840, only the upper class and the upper bourgeoisie owned framed prints, some of which were imported from England and France and passed down through generations. Above all, mythological and allegorical themes, views, and literary and historical motifs were preferred. Up until around 1830, copperplate engravings , as well as etchings , aquatints and mezzotints were common. Then lithography prevailed, initially with portraits .

After 1840, the exhibitions and reproduction orders from the newly emerging art associations, as well as news from major art exhibitions, stimulated interest in art from the bourgeoisie. The middle bourgeoisie also increasingly acquired wall picture prints. The picture needs of the lower social classes were covered by a rich supply of picture sheets . A particular preference developed for literary motifs; works of genre painting were also readily reproduced. Humorous scenes like salon affairs, boyish pranks, and pub fights were also popular.

Better mural prints still used copperplate engraving; the price was correspondingly high. The steel engraving developed in 1820 made it easier to work and a longer-run reproduction. Works made according to this technique sometimes achieved large editions, but were no longer in demand after a few decades. The expressive chalk lithograph with its soft transitions, on the other hand, quickly won the favor of image consumers and rose to become the most important reproduction technique. The quality of the prints so produced varied considerably. By using different working methods such as pen, brush or chalk style, the lithographs could be provided with special effects and effects.

1860-1890

In the second half of the 19th century, the development of mural printing underwent fundamental changes. Increasing prosperity and new printing techniques that allowed mass production expanded the group of consumers considerably. The advertising and demonstration of paintings by the printing industry in the context of world, industrial and trade exhibitions also led to widespread acceptance of printed images. The fact that murals were advertised as accessories for home furnishings made cultural critics suspicious of the term “furniture pictures”. The expansion of the railway network enabled sales through shops and door-to-door sales. In the middle class, the art associations continued their activities. In addition to the bourgeoisie, the needs of the “minor officials and craftsmen” and the “proletariat” were also taken into account by dividing the goods into quality classes depending on the target group.

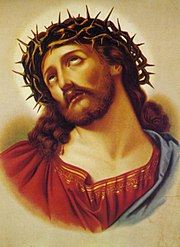

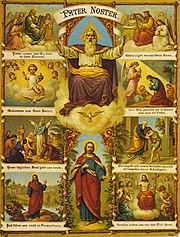

In contrast to the print quality, the choice of image motifs largely matched. The genre painting with its romantic family and love scenes dominated the market; Mythological, historical and literary topics also took a back seat in the middle classes. Patriotic motifs such as portraits of princes or battle scenes as well as depictions of festive occasions and literary intellectuals continued to be an integral part of the offer. The sector of religious motifs was even larger. It had a firm place, especially in rural, Catholic areas, whereas in the middle class only a few standard motifs such as the knocking Christ, the good shepherd or the grace period remained.

The galvanography perfected by Leo Schöninger , with which copper engravings could be reproduced more easily, was intended for more discerning art lovers. It was replaced by photographs of oil paintings, engravings and sculptures, which became increasingly popular from 1865 onwards. While the photographic reproduction was enthusiastically received by art historians, the murals produced with this technique were viewed with skepticism, since they were not made from the original oil painting itself, but from reproduction engravings and lithographs. A disadvantage of the photographs was that they yellowed quickly. From the 1870s onwards, copperplate engraving fell in popularity. Concomitants of the time were on André Disdéri declining " Galleries modern masters ' in business card format and the Fotografietonbilder that should mimic a photograph.

The best-selling items, however, were the chromolithographs , which could also be used to reproduce colored templates. They were invented by Godefroy Engelmann and later improved by Winckelmann & Sons . As expensive "color print pictures" they were used to reproduce paintings for the bourgeoisie; as mass-produced goods of lower quality, so-called “oil prints” (also “oil color prints”, “oil picture prints”), they covered the needs of less affluent layers. From around 1875 they made serious competition for the chalk lithographs. In addition to chromolithographs, photomechanical reproduction processes such as collotype printing and heliogravure were established , which were known under many other names with only minor technical differences.

1890-1945

Mural prints now reached all social classes and were tailored to the respective class of buyers in taste and price. Image printing experienced competition from artist and art postcards . During the First World War , the art trade accommodated the general mood through patriotic motives. Landscape and genre representations were still the most popular. Religious themes remained popular, but adapted to the changing times by removing old-fashioned-looking pictorial formulations. Sports motifs also appeared from around 1900. The number of chromolithographs slowly declined as photomechanical reproduction processes improved. Color prints such as tri-color prints or collotype prints were predominant.

In the 1920s, secular and religious bedroom pictures with motifs such as "fairy dance" or "wedding dream" experienced their heyday. After the First World War, the images of princes ceased to exist; they were only made for foreign countries. In the 1930s the number of religious motifs declined. Instead, it became customary to classify the images according to the motif for their intended use - dining, living, men's or children's rooms. Pictures of landscapes and children replaced genre pictures. In addition, so-called “national visual art” emerged with portraits of the Führer and Hindenburg , heroic landscapes and idealized depictions of farmers and workers. Photomechanical reproduction processes such as color collotype printing and color intaglio printing finally replaced old processes.

After 1945

The picture habits after the Second World War have been little explored. The offset printing took place in Germany after the war general distribution. Initially, attempts were made to restore the furnishings that were destroyed in the war. Refugees in particular saw mementos based on old motifs as mementos. Parallel to the "modern furniture store" of the 1960s, new, attractive motifs developed, such as the busty gypsy. With the availability of larger living space and cheaper furniture in Central Europe, the oversized bedroom image had its day; the modern apartment rather required many portrait-format pictures for the narrow wall surfaces between the furniture. It was not until the posters , which were particularly popular among young people and mainly showed idols from film, music, sports and politics, that giant images were able to be housed again. In the lower social classes, apart from posters, landscapes, animals and flowers became the most popular groups of subjects. The "real original paintings" experienced a considerable upswing. These cheap painting copies by old masters or from the more recent motifs of mural printing were painted in rows by Belgian prison inmates, among others. The modern art print works with a more or less high number of printing colors in order to guarantee color fidelity.

Motifs and artists

For a majority of mural print buyers, image content was more important than artistic and aesthetic features. Art publishers took this into account by dividing their catalogs according to image motifs. The templates for the reproduction prints can be divided into two categories. On the one hand, there were so-called “ gallery works ”, which were made from paintings from the large picture galleries. Some works were particularly popular here, such as The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci or the Sistine Madonna by Raphael . In mural printing, however, priority was given to the “modern masters” - the contemporary name - who drew attention to themselves through art exhibitions, reviews and images in family and art magazines and were selected by the publishers according to the desired subject.

Secular motives

Children and family scenes were among the most popular genre themes. The forerunner of the children's genre was Dutch genre painting of the 17th century. It was later cultivated by Jean-Baptiste Greuze , Jean Siméon Chardin and English portraitists before it appeared in Germany around 1830. The images were always characterized by ideas of purity and innocence. Well-known painters of simple play scenes without any particular statement were Meyer von Bremen , Ludwig Knaus , Hermann von Kaulbach and Paul Friedrich Meyerheim . Another type of image shows children with an adult appearance, as bearers of hope according to the role expected, together with titles such as “the little soldier”. The color scheme has been adapted to the respective national colors. Models were works like The Children of Nobility (1841) by Alfred Chalon . Another group of images was used to illustrate civic virtues in an educational way using the example of “kind-hearted” or self-sacrificing children. Les révélations by Edouard Girardet was widespread among the school scenes and was widely available in Germany under the title “That's a good thing!” Together with its counterpart “You will get the rod!”.

From around 1900, the content of the children's pictures changed in favor of the cute, sweet girl influenced by Corneille Max . Many depictions of a mother with a toddler can be described as profaned images of Mary . A popular motif was “the first step”. The pictures by Héloïse Leloir were particularly popular, all of which were reproduced as color lithographs. In the 1920s, mother-child representations also appeared among bedroom pictures; here the painters Alfred Schwarz and Ms. Laubnitz were most in demand. The family scenes addressed a variety of aspects, such as the intergenerational relationship or teaching.

Beauties and erotica. Graces and charming girls' heads, including first names, allegories, odalisques and ancient goddesses, were an essential part of the catalog for art publishers . Models were English steel engraving series such as “Byron's Beauties” (1836) by the London publisher Find or Alfred Chalon's “Gallery of Grace” (1832) and Edward Henry Corbould's “Gems of Beauty” (1840). French publishers also offered color engraving series around 1820, which were later taken over and converted by the Berlin publishers. Around 1850 the “rustic beauties” of various English painters were very successful; the rural beauties depicted there were often reproduced under the title The Daughter of ...

The allegorical female figures depicted in the beauty galleries, such as the “ball lady”, “flower friend” or even the half-naked “Metschunka, the favorite slave” sometimes served as pin-up girls. Specially produced erotic works were reserved for a smaller, wealthy group of customers, such as the lascivious copperplate offered by August Scherl in 1925, entitled “Two Puppets”. The Berlin publishing house Richard Bong had already advertised such works before the First World War. The lush beauties of oriental painting with titles such as “Haremsdame”, “Perle des Orients” or “Odalisque” were exported to Turkey and the Middle East by Berlin publishers. As the archived prohibited lists show, both individual sheets and entire publisher's catalogs fell victim to state censorship , especially if they targeted the lower class . The sentencing of publishers to fines for disseminating indecent images has also been reported frequently.

Lovers. Representations of lovers - in France "lithographies romantiques", in England "sentimentals" - were widespread. The standard motifs included those by the painter Frank Stone with titles such as First Appeal , Last Appeal or Mated ; from around 1870 onwards they were superseded by the social scenes of his son Marcus . The historical scenes of John Everett Millais like The Black Brunswicker or A Huguenot… were also in demand .

Literature and fairy tale scenes. There were literary motifs as single sheets, counterparts and suites of four; the latter were particularly common in France. Art publishers in the 1850s and 60s, had supported even older paintings with literary content, the genre reached in 1870 with Goethe, Schiller and Shakespeare galleries of painters such as Wilhelm von Kaulbach , August von Kreling and Ernst Stückelberg a Heyday. The subjects implemented included William Tell , The Hunchback of Notre-Dame , The Count of Monte Christo and Romeo and Juliet . Also Grimm's Fairy Tales served in the 19th century often as a template.

Patriotic motives. The patriotic genre, which included portraits of princes, historical pictures and battle scenes, was widespread across Europe and probably the most extensive of all branches. The portraits of princes emerged from the tradition of portrait engravings in the 18th century, but gained considerably in importance with lithography. Pictures of princes in the home or workshop became a matter of course and enjoyed a boom during the first years of the First World War. From 1933 onwards, the National Socialist image collection with pictures of leaders, sports, aviation and fleet scenes as well as glorifying depictions of soldiers at the front increased sharply in the First World War.

Peasant genre. The depictions of rural life go back to 17th century Dutch painting. The shepherd genre was added in the 18th century. As a result of an increased interest in folklore and traditional costumes, from 1840 on, circles such as the Kronberg painter colony concentrated on depictions of rural life; their works have often been reproduced. In the 1850s and 60s, the pictures of the former coach painter John Frederick Herring senior served as the basis for lithographs for the Berlin publishers. At the beginning of the 20th century, the genre pictures by Franz Defregger and others became popular.

Animal and hunting motifs. The animal scenes mainly showed cats, dogs and horses. In the case of the cat pictures, reproductions after Mathilde Aïta , CH Blair and Horatio Henry Couldery were widespread. Depending on the scene, dogs were depicted as guards, hunting helpers or companions, here the works of Edwin Landseer and Richard Ansdell often served as models. Horses were used in the context of war, hunting, sport and horse service . In battle painting, Ansdell's Fight for the Standard (1848) aptly expressed the heroism of rider and horse; Reproductions of the picture have also been distributed overseas and even in New Zealand. Franz Krüger's horse pictures were also popular in Germany. The representations of racing horses, along with details of name, stud and victories, originated in England and were aimed at racing enthusiasts. Among the German painters, Carl Steffeck and Heinrich Sperling were most in demand here. The horse scenes in rural surroundings by John Frederick Herring were more popular among German art publishers.

Hunting pictures were popular with popular art publishers throughout the 19th century, including humorous scenes. In the German area were Karl Friedrich Schulz , Christian Kröner , Carl Zimmermann and Moritz Müller frequently reproduced. In addition to Landseer and Ansdell, Henry Alken's hunting scenes were very popular.

Humorous motifs. The humorous genre took about the same place as the historical motifs. Marriage scenes and mishaps were often depicted. The drinking pictures also took up a large space, with those by Eduard Grützner being the most common.

Views and Landscapes. While in the 19th century the depictions of well-known cities and areas predominated, in the oil printing industry more general, almost always unsigned mood images with titles such as “Alphütten im Gasterntal” or “Die Dorfschmiede” were predominant. After 1900 Hermann Rüdisühli became one of the most sought-after painters for sentimental and heroic landscapes.

Religious motifs

In the lower social classes and in the country, religious motifs generally predominated. The art publishers divided their works into “secular” and “sacred” motifs, but left these two categories different. For the Berlin publishers, religious themes made up a quarter of the total production, while in Munich they always made up the majority of the program. The buyers' denominations only played a role in the case of images of saints , pilgrimage souvenirs and Sacred Heart pendants.

Bible scenes. Certain scenes crystallized from the material of the Old Testament , which were often depicted and reproduced: the story of Joseph and Moses , the judgment of Solomon as well as scenes about Ruth , Judit , Rebekah , Rachel , Susanna and Delilah . The genre scenes "Exposure and Finding Mosis" were mainly made after Paul Delaroche and achieved wide distribution.

The subjects based on the New Testament were much more common . The prints made after the Nazarenes , especially the type of the knocking, comforting and rewarding Christ, found their place in the upper middle class. Of the parables, that of the prodigal son was by far the most popular. The painters whose works were redrawn for mural printing included Bernhard Plockhorst , Enrico Schmidt , Johann Roth , Wilhelm Steinhausen and Heinrich Ferdinand Hofmann .

Other topics. An image widely used in European and American mural printing was The Infant Samuel (1776) by Joshua Reynolds , which was launched just a year after its completion. Among the very popular guardian angel images, morning and evening prayers and the angel guarding a pair of children on the precipice or on a bridge were frequent themes. In the Anglo-Saxon region, the counterparts “Trust in God” and “Mercy”, which spread a rock jutting out of the sea with a cross to which young girls cling, were spread in many variations. They go back to the pictures titled Rock of Ages and Simply to the Cross I Cling by Johannes Adam Oertel ; however, the motif can already be found in the early 17th century.

The cemetery pictures, which were not taboo in the 19th century, were also a regular part of the sales catalogs. They were created mainly by English genre painters such as John Callcott Horsley since the middle of the century. Related are the so-called dream images, which contain wishes or hopes. Thomas Brooks ' pictures The Mother's Dream and The Believer's Vision were particularly widespread .

Use and function

Private living spaces

Together with private portraits, prints formed the main component of the lavish bourgeois wall decorations of the Biedermeier period . Pictures were even hung on window and door niches. As contemporary interior descriptions and recommendations from art publishers suggest, the choice of motifs varied from room to room.

In the salon hung in the plurality of oil paintings. At best, art association contributions were accepted as reproduction graphics. Historical representations, landscapes and reproductions of classical masters dominated. A favorite was Arnold Böcklin's island of the dead , which was copied very often. The dining room, on the other hand, only housed carefree motifs such as still lifes . In the master bedroom a wide range of mythological themes about drinking pictures up was found to be hunting motifs, even on liberal views they took no offense. In contrast, charming, decorative and lovely genre scenes prevailed in the boudoir . Later, more serious, religious motives were also recommended. The bedroom pictures that were hung over the double beds did not exist until the 1910s. For the children's room, fairytale depictions were primarily intended, but also guardian angel images, especially as oil prints. The house blessing always hung in the hallways .

In the countryside, religious motifs, whether lithographs or oil prints, were far more numerous. In Catholic areas, they made up most of the images. A lot is known about the picture habits in the urban slums thanks to the photographs of the Berlin Housing Enquête , which was organized from 1903 to 1920 by the health insurance company. Where the former bourgeois apartment had to give way to a miserable dwelling after social decline, the wall decorations from the better days, including house blessings, were usually kept.

Public spaces

The inexpensive printmaking was also used in churches and chapels, for example at the confessionals or stations of the cross . For the latter, all art publishers specializing in religious graphics offered a series of 14 sheets. Church circles always emphasized the educational effect they hoped for by attaching suitable pictures in orphanages, children's homes, hospitals, insane asylums, poor houses and prisons. The wall decorations in schools have repeatedly been the subject of discussions. Images of princes, religious motifs and views were the most common. Several art publishers offered papers that were perceived as family-friendly, patriotic and artistically impeccable under the catchphrase “For school and home”. In addition to the typical pub image, historical and literary topics were widespread in the inns. Hotels preferred to have motifs that were neither too old-fashioned nor too avant-garde. Landscapes and views as well as reproductions of well-known paintings dominated here, for example Vincent van Gogh's sunflowers .

Functions

The purchase of mural prints primarily met a jewelry and decoration need. In the 19th century, mural prints were generally equated with art, regardless of their thousandfold reproduction and regardless of the respective social class. The possession of art served the prestige and underlined by the picture content well-being and education. The new mass-produced mural was generally welcomed as a way of conveying art to all classes. The mass newspaper Die Gartenlaube 1884 was enthusiastic about the "modern art industry":

“ The beautiful luxury of rich people is becoming more and more a common property of the bourgeoisie, so that a sense of beauty and cheerful domesticity go up from the Bel floors to the attic and down the cellar, shut up rudeness and ugliness and paralyze your fist. "

Only the bedroom pictures were exposed to vehement criticism in the 1920s.

Certain motifs served to demonstrate a group-specific commitment. A patriotic sentiment was expressed, for example, through pictures of historical and warlike events, allegorical representations and especially through portraits of princes and generals. When picture prints with religious motifs hung in the salon or living room, they underlined the basic Christian attitude of the house. Mythological image content, on the other hand, indicated a humanistic education of the owner. Commemorative and gift sheets such as confirmation, communion and wedding souvenirs are identified as such by their text or notes on the back.

The printing industry

Redrawing, preparation and decoration

The original image of the mural prints was mostly an oil painting. However, the finished lithographs were not reproduced directly from the original, but from a copper engraving, mezzotint, aquatint or steel engraving. Photographic reproductions were not made from the original oil painting, but from such templates. This intermediate step was a prerequisite for the rapid implementation of new publications. On the other hand, the art publishers also commissioned work that was geared to their publishing program.

Depending on the target group of customers, the publishers trivialized and popularized the original works. As with other types of popular graphics , it was possible to convey a more catchy and touching appearance compared to the original by changing the image composition, reducing image content, depth, perspective and image elements, changing the appearance of people, adding ornaments or other interventions. Publishers of low quality oil prints employed unknown draftsmen and lithographers. The names of the lithographers - who always worked for several publishers at the same time - can only be identified in the case of publishers targeting the middle and upper middle class. Among the better-known names were CF Schwalbe (* 1816), a co-founder of the pleasant, soft drawing style typical of Berlin publishers, Gustav Bartsch (since 1847 in Berlin), who also worked as a genre painter, Wilhelm Bülow (recorded from 1847) and W. Jab (active from 1838). Before the time of color printing, but also with the advent of photo engravings, colorists and colourists were responsible for partially or fully painting the template. In contrast to colorists, the term colorist only included unskilled workers for rough work with stencils.

Mural prints were provided with the title of the picture, often supplemented by verses, and the publisher's address. The latter was omitted when it was cut off or covered with the passe-partout . The painter's name was often kept secret and occasionally replaced by that of the draftsman. The addition “comp.” (= Composuit) should indicate an artistic authorship that did not exist. Only with the higher quality lithographs was a complete imprint retained, as was the rule in the 18th century for reproduction graphics of paintings. It was customary to give the picture surface a structure, usually an imitation linen weave, by calendering or embossing . Covering with varnishes and varnishes as well as decorating with tinsel , mica or embroidery thread was also common.

Manufacturing and sales

Kunstanstalt was the most common among the names of the companies involved in the manufacture, publication and sale of wall picture prints . This general term could refer to a manufacturer, printer, or distributor, possibly for other products such as postcards, stained glass, and handicrafts. In contrast to this, art publishers usually did not deal with printing, but only with publication. The company commissioned its own printing companies with the printing, especially since only these had the necessary specialists and machines for complex reproduction techniques. The two branches of art establishment and art publishing were combined under the term art publishing establishment . The chromolithographic institutions and oil color printing institutes combined publishing and printing. The institutions trading as art dealers or art dealers were entrusted with the distribution of art sheets and other art objects .

The beginning of the mural print production was the art publisher who acquired the templates for the reproduction print; the price for it was very different. In addition, the engraver, who sometimes took years of work to make the printing plate, had to be paid. For example, Paul Sigmund Habelmann received 36,000 marks for his engraving of the “Children's Festival” from Ludwig Knaus . When photomechanical reproduction processes became established after around 1890, the purchase price of paintings and reproduction rights were adjusted to the lower costs of drawing and printing.

Wholesaling took place between publishers and commission business or between publishers and assorters. The publishers advertised in trade magazines and sent representatives who visited the art dealers regularly to draw attention to new publications and to take orders. Image prints were always also export items; especially after the First World War, the demand for mural prints from abroad increased. Annual fairs were an important trading point, and street and peddling trade was also widespread. The retailers advertised their pictures in art and family magazines, daily newspapers and in shop windows or by sending out brochures.

Research history

The first ethnographic research on the subject of wall decorations appeared in the late 1960s after a catalog of lithographs by the Frankfurt art publisher Eduard Gustav May was created. At the same time, popular, " kitschy " wall decorations became a collection item. The research is not about an artistic or stylistic evaluation of the pictures, but about the social role of mural printing. In 1973 the pioneering exhibition “Die Bilderfabrik” was shown in the Historical Museum in Frankfurt am Main , for which a catalog of the same name was published. Since then, mural printing has occasionally been the subject of exhibitions, the catalogs of which form an integral part of the research.

literature

- General literature

- Wolfgang Brückner and Christa Pieske : The picture factory. Documentation on the art and social history of industrial wall decoration production between 1845 and 1973 using the example of a large company , Historisches Museum Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt 1973.

- Wolfgang Brückner: Elfenreigen, wedding dream. Die Öldruckfabrikation 1880–1940 , DuMont Schauberg, Cologne 1974. ISBN 3-7701-0762-4

- Bruno Langner: Evangelical world of images. Prints between 1850 and 1950 (= publications and catalogs of the Fränkisches Freilandmuseums 16), Fränkisches Freilandmuseum, Bad Windsheim 1992. ISBN 3-926834-22-6

- Christa Pieske: Pictures for everyone. Mural prints 1840–1940 (= writings of the Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde Berlin 15), Keyser, Munich 1988. ISBN 3-87405-188-9

- bibliography

- Wolfgang Brückner: Massenbildforschung: a bibliography until 1991/1995 (= publications on folklore and cultural history 96). Institute for German Philology, Würzburg 2003.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Pieske: Pictures for everyone , p. 16

- ↑ Pieske: Pictures for everyone , p. 27

- ↑ Martin Scharfe: "Murals in workers' apartments - To the problem of bourgeoisie", in: Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 77, 1981, pp. 17-36.

- ↑ Wolfgang Brückner: "Kleinbürgerlicher und Wohlstandsbürgerlicher Wandschmuck im 20. Jahrhundert", in: Kunst und Konsum - Massenbildforschung (= folklore as historical cultural studies 6; publications on folklore and cultural history 82), pp. 407–444, here p. 442. Würzburg 2000

- ^ Pieske: Pictures for everyone , p. 79

- ^ Pieske: Pictures for everyone , p. 39.

- ↑ Pieske: Pictures for everyone , p. 46

- ^ Pieske: Pictures for everyone , p. 57

- ↑ Quoted in Brückner, Pieske: Die Bilderfabrik , p. 65

- ↑ Der Kunsthandel 1927, p. 102. Quoted in Pieske: Bilder für jedermann , p. 155