Leonardo da Vinci

Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

Leonardo da Vinci | |

|---|---|

Portrait in red chalk, circa 1512 to 1515.[1] | |

| Born | Leonardo di Ser Piero da Vinci |

| Died | May 7, 1519 |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Apprentice to Andrea del Verrocchio |

| Known for | painting, engineering, architecture, astronomy, paleontology, anatomy, geometry, mathematics, physics, dynamics, metaphysics |

| Movement | High Renaissance |

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (April 15, 1452 – May 2, 1519) was an Italian polymath: scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, painter, sculptor, architect, musician, and writer.

He was born and raised in Vinci, Italy, the illegitimate son of a notary, Messer Piero, and a peasant woman, Caterina. He had no surname in the modern sense; "da Vinci" simply means "of Vinci". His full birth name was "Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci", meaning "Leonardo, son of (Mes)ser Piero from Vinci."

Leonardo has been described as the archetype of the "Renaissance man", a man infinitely curious and equally inventive. He is widely considered to be one of the greatest painters of all time, and the man with the most diversely prodigious talent ever to have lived.

It is primarily for his painted works that Leonardo has been held in renown, even during his own lifetime. Two of his works, the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper occupying unique positions as the most famous, the most illustrated and most imitated portrait and religious painting of all time, only approached in fame by Michelangelo's Creation of Adam. His drawing of the Vitruvian Man is also iconic.

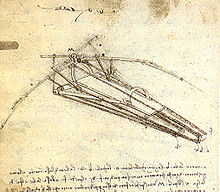

As an engineer, Leonardo conceived ideas vastly ahead of his own time, conceptually inventing a helicopter, a tank, the use of concentrated solar power, a calculator, a rudimentary theory of plate tectonics, the double hull, and many others. Relatively few of his designs were constructed or were feasible during his lifetime.[2] Some of his smaller inventions such as an automated bobbin winder and a machine for testing the tensile strength of wire entered the world of manufacturing unheralded.

In practice, he greatly advanced the state of knowledge in the fields of anatomy, astronomy, civil engineering, optics, and the study of water (hydrodynamics). Of his works, only a few paintings survive, together with his notebooks (scattered among various collections) containing drawings, scientific diagrams, and notes.

Biography

Early life

Leonardo was born on April 15, 1452, in Anciano, a village near the town of Vinci in the lower valley of the Arno, within the territories of Florence. [3]

Leonardo only recalled two incidents of his childhood. One, which he regarded as a premonition, was when a hawk dropped from the sky and hovered over his cradle, its tail feathers brushing his face.

The second incident occurred while exploring in the mountains. He discovered a cave and recorded his emotions at being, on one hand, terrified that some great monster might lurk there and on the other, driven by curiosity to find out what was inside.

At the age of five, he went to live in the household of his father, grandparents and uncle, Francesco, in the small town of Vinci, where his father had married a sixteen-year-old girl called Albiera, who loved Leonardo but unfortunately died young.

Vasari tells the story of how a local peasant requested that Ser Piero asked his talented son to paint a picture on a round plaque. Leonardo responded with a painting of snakes spitting fire which was so terrifying that Ser Piero sold it to a Florentine art dealer, who sold it to the Duke of Milan. Meanwhile, having made a profit, Ser Piero bought a plaque decorated with hearts and flowers which he gave to the peasant.

Section references: Liana Bortolon [4], Vasari[5]

Training

In 1466 Leonardo was apprenticed to one of the most proficient artists of his day, Andrea di Cione, known as Verrocchio. The workshop of this famous master was at the centre of the intellectual currents of the day. Among those who were apprenticed or associated with the workshop were Perugino, Botticelli, and Lorenzo di Credi, assuring the young Leonardo of an advanced education in all branches of the humanities.

As a fourteen-year-old apprentice Leonardo would have been trained in all the countless skills that were employed in a traditional workshop in which the artists were regarded primarily as craftsmen and only a master such as Verrocchio had social standing.

The products of Verrochio’s workshop would have included decorated tournament shields, painted dowry chests, christening platters, votive plaques, small portraits, and devotional pictures. Major commissions included altarpieces for churches, and commemorative statues. Although many craftsmen specialised in tasks such a frame-making, gilding and bronze casting, Leonardo would have been exposed to a vast range of technical skills and had the opportunity to learn drafting, chemistry, metallurgy, metal working, plaster casting, leather working, mechanics and carpentry as well as the obvious artistic skills of drawing, painting, sculpting and modelling.

Although Verrocchio appears to have run an efficient and prolific workshop, few paintings can be ascertained as coming from his hand. And on one of those, Vasari tells us, Leonardo collaborated.

The painting is the Baptism of Christ. According to Vasari, Leonardo painted the young angel holding Jesus’ robe and Verrocchio, overwhelmed by the sweetness of the angel’s expression, its moist eyes and lustrous curls, put down his brush and never painted again. This is probably an exaggeration. The truth is that on close examination the painting reveals much that has been painted or touched up over the tempera using the new technique of oil paint. The landscape, the rocks that can be seen through the brown mountain stream and much of the figure of Jesus bears witness to the hand of Leonardo.[5]

The other creation of Verrocchio’s which is particularly pertinent to the young Leonardo is the bronze statue of David, now in the Bargello Museum.[6] Apart from the exquisite quality of this work of art, it is significant in holding the claim to be a portrait of the apprentice, Leonardo. If this is the case, then in the figure of David we see Leonardo as a thin muscular boy, quite different to the rounded androgynous figure made by Verrocchio’s teacher, Donatello. [7] It is also suggested that the Archangel Michael in Verroccio's Tobias and the Angels is a portrait of Leonardo.[6]

When Leonardo was twenty he joined the Guild of St Luke, the guild of artists and doctors of medicine, but even after his father set him up in his own workshop, his attachment to Verrocchio was such that he continued to work with him.

Section references: Bortolon[4], Vasari[5], della Chiesa[6], Martindale [8]

Leonardo's Florence

Leonardo commenced his apprenticeship with Verrocchio in 1466, the year that Verrocchio’s master, the great Donatello, died. Uccello was a very old man, Piero della Francesca, Luca della Robbia and Fra Filippo Lippi were in their sixties. The successful artists of the next generation were his teacher Verrocchio, Antonio Pollaiuolo and the portrait sculptor, Mino da Fiesole.

Leonardo was the contemporary of Botticelli, Ghirlandaio and Perugino who were all slightly older than he was. He would have met them at the workshop of Verrocchio, with whom they had associations, and at the Academy of the Medici, Botticelli being a particular favourite of the family. These three were among those commissioned to paint the walls of the Sistine Chapel. Leonardo was not part of this prestigious commission. Leonardo was also the contemporary of the two architects, Bramante and Sangallo

In 1476, during the time of Leonardo’s association with Verrocchio’s workshop, Hugo van der Goes arrived in Florence, bringing the “Portinari Altarpiece” and the new painterly techniques from Northern Europe which were to profoundly effect Ghirlandaio, Perugino and others. In 1479, the Sicilian painter Antonello da Messina who worked exclusively in oils, travelled north on his way to Venice where an older painter, Giovanni Bellini adopted the media of oil painting, quickly making it the preferred method in Venice.

Leonardo’s political contemporary was Lorenzo Medici (il Magnifico) who was three years older and his popular brother Giuliano, slain in the Pazzi Conspiracy. Ludovico il Moro who ruled Milan between 1479-99 was also of Leonardo’s age.

Through the Medici, Leonardo came to know the older Humanist philosophers of whom Marsiglio Ficino, proponent of Neo Platonism and Cristoforo Landino, writier of commentaries on Classical writings, were foremost. Also associated with the Academy of the Medici was Leonardo's contemporary, the brilliant young poet and philosopher Pico della Mirandola.

Although usually named together as the three giants of the High Renaissance, Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael were not of the same generation. Leonardo was 23 when Michelangelo was born and 31 when Raphael was born. The short-lived Raphael died in 1520, the year after Leonardo, but Michelangelo went on creating for another 45 years.

Section references: Brucker[9], Rachum[10].

Professional life

The earliest known dated work of Leonardo's is a drawing done in pen and ink of the Arno valley, drawn on 5 August, 1473. It is assumed that he had his own workshop between 1476 and 1478, receiving two orders during this time.

From around 1482 to 1498, Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan [1], employed Leonardo and permitted him to operate his own workshop, complete with apprentices. It was here that seventy tons of bronze that had been set aside for Leonardo's "Gran Cavallo" equestrian statue (see below) was cast into weapons for the Duke in an attempt to save Milan from the French under Charles VIII in 1495.

When the French returned under Louis XII in 1498, Milan fell without a fight, overthrowing Sforza [2]. Leonardo stayed in Milan for a time, until one morning when he found French archers using his life-size clay model of the "Gran Cavallo" for target practice. He left with Salaiano, his assistant and intimate, and his friend Luca Pacioli (the first man to describe double-entry bookkeeping) for Mantua, moving on after two months to Venice (where he was hired as a military engineer), then briefly returning to Florence at the end of April 1500.

In Florence he entered the services of Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, acting as a military architect and engineer; with Cesare he travelled throughout Italy: in those years, he was in Forlì, where he met Caterina Sforza (one of possible model women for Mona Lisa), and at Cesenatico, whose port Leonardo designed.

In 1506 he returned to Milan, now in the hands of Maximilian Sforza after Swiss mercenaries had driven out the French.

From 1513 to 1516, he lived in Rome, where painters like Raphael and Michelangelo were active at the time, though he did not have much contact with these artists. However, he was probably of pivotal importance in the relocation of David (in Florence), one of Michelangelo's masterpieces, against the artist's will. Most of his most prominent pupils or followers in painting either knew or worked with him in Milan, including Marco D'Oggione[11], Bernardino Luini, and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio.

In 1515, François I of France retook Milan, and Leonardo was commissioned to make a centrepiece (a mechanical lion) for the peace talks between the French king and Pope Leo X in Bologna, where he must have first met the King. In 1516, he entered François' service, being given the use of the manor house Clos Lucé (also called "Cloux"; now a museum open to the public) next to the king's residence at the royal Chateau Amboise, where he spent the last three years of his life. The King granted Leonardo and his entourage generous pensions: the surviving document lists 1,000 écus for the artist, 400 for Count Francesco Melzi, (his pupil, named as "apprentice"), and 100 for Salaiano ("servant"). In 1518 Salaiano left Leonardo and returned to Milan, where he eventually perished in a duel. François became a close friend. Some twenty years after Leonardo's death, François told the artist Benevenuto Cellini that he believed that "No man had ever lived who had learned as much about sculpture, painting, and architecture, but still more that he was a very great philosopher."

Leonardo died at Clos Lucé, France, on 2nd May, 1519 (Romantic legend said that he died in François' arms). According to his wish, sixty beggars followed his casket. He was buried in the Chapel of Saint-Hubert in the castle of Amboise. Although Melzi was his principal heir and executor, Salaiano was not forgotten; he received half of Leonardo's vineyards.

Assistants and pupils

Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno,[12] nicknamed Salai or il Salaino ("The little devil), was described by Giorgio Vasari as "a graceful and beautiful youth with fine curly hair, in which Leonardo greatly delighted."

Il Salaino entered Leonardo's household in 1490 at the age of ten. The relationship was not an easy one. A year later Leonardo made a list of the boy’s misdemeanours, calling him "a thief, a liar, stubborn, and a glutton." The "Little Devil" had made off with money and valuables on at least five occasions, and spent a fortune on apparel, among which were twenty-four pairs of shoes.

Nevertheless, Leonardo’s notebooks during their early years contain many pictures of a handsome, curly-haired adolescent. Il Salaino remained his companion, servant, and assistant for the next thirty years. [13]

As a painter, the artistic merit of Salaino’s work has been a matter of debate. In 1515 he painted, under the name of Andrea Salai, a nude portrait of "Lisa del Giocondo", based upon the Mona Lisa and known as Monna Vanna.[3] The Mona Lisa was bequeathed to Salaino by Leonardo, and in Salaino's own will at was assessed at the high value of £200,000.

In 1506, Leonardo took as a pupil Count Francesco Melzi, the fifteen-year-old son of a Lombard aristocrat. Salaino, at first jealous of Melzi, eventually accepted his continued presence and the three undertook journeys throughout Italy. Melzi became Leonardo's life companion, and is considered to have been his favourite student. He travelled to France with Leonardo and was with him until his death.

Personal life

Leonardo had many friends who are figures now renowned in their fields, or for their influence on history. These included Cesare Borgia, in whose service he spent the years 1502 and 1503. During that time he also met Niccolò Machiavelli, with whom later he was to develop a close friendship. Also among his friends are counted Franchinus Gaffurius and Isabella d'Este, whose portrait he drew while on a journey which took him through Mantua. Beyond friendship, Leonardo kept his private life secret. He commented "the act of procreation and anything that has any relation to it is so disgusting that human beings would soon die out if there were no pretty faces and sensuous dispositions".

Leonardo had no intimate relationships with women. However his contemporaries represented him as a passionate man, and all his life he surrounded himself with beautiful young men, at times even getting into scrapes with the law over his alleged erotic flings with males. His relationships with his pupils Salaino and Melzi, first taken on in their mid-teens or earlier, are widely considered to have been passionate, not least by Melzi himself. His love affairs with young males reflect the cultural milieu in which he lived, where pederasty was widely practiced by men in all walks of life.[14]

Leonardo’s painting

Despite the recent awareness and admiration of Leonardo as a scientist and inventor, for the better part of four hundred years his enormous fame rested on his achievements as a painter and on a handful of works, either authenticated or attributed to him that have been regarded as among the supreme masterpieces ever created.

These painting are famous for a variety of qualities which were to be interminably discussed and speculated about by connoisseurs and critics, imitated by students, and gazed at day after day by the public in thousands. Among the qualities that make Leonardo’s work unique are the innovative techniques that he used in laying on the paint, his detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, botany and geology, his interest in physiognomy and the way in which humans register emotion in expression and gesture, his innovative use of the human form in figurative composition and his use of the subtle gradation of tone.

Mona Lisa

All these qualities come together in his most famous work, the small portrait known as the Mona Lisa or “la Giocconda”, the laughing one. The painting is, in particular, famous for the elusive smile on the woman’s face, its particular quality brought about perhaps by the fact that the artist has subtly shadowed the corners of the mouth and eyes so that the exact nature of the smile cannot be determined. The shadowy quality for which the work is renowned came to be called “sfumato” or Leonardo’s smoke. Other characteristics found in this work are the unadorned dress, in which the eyes and beautiful hands have no competition from other details, the dramatic landscape background in which the world seems to be in a state of flux, the subdued colouring and the extremely smooth nature of the painterly technique, employing oils, but laid on much like tempera and blended on the surface so that the brushstrokes are indistinguishable.

Early works

Leonardo’s early works begin with the Baptism of Christ in conjunction with Verrocchio. Two other paintings appear to date from his time at the workshop, both of which are Annunciations. One is small, 59 cms long and only 14 cms high. It is a “predella” to go at the base of a larger composition, in this case a painting by Lorenzo Di Credi from which it has become separated. The other is a much larger work, 217 cm long. In both these Annunciations Leonardo has used the very formal arrangement of Fra Angelico’s two well known pictures of the same subject, the Virgin Mary sitting or kneeeling to the right of the picture, approached from the left by an angel in profile, with rich flowing garment, raised wings and bearing a lily.

In the smaller picture Mary averts her eyes and folds her hands in a gesture that symbolised submission to God’s will. In the larger picture, however, Mary is not in the least submissive. The beautiful girl, interrupted in her reading by this unexpected messenger, puts a finger in her bible to mark the place and raises her hand in greeting. This calm young woman accepts her role as the Mother of God not with resignation but with confidence. In this painting the young Leonardo presents the Humanist face of the Virgin Mary, a woman who recognises humanity’s role in God’s incarnation.

Paintings of the 1480s

In the 1480s Leonardo received two very important commissions, and commenced another work which was also of ground-breaking importance in terms of compositon. Unfortunately two of the three were never finished and the third took so long that it was subject to lengthy negotiations over completion and payment. One of these paintings is the of St Jerome in the wilderness. Although the painting is barely begun the entire composition can be seen and it is very unusual. Jerome, as a penitent, occupies the middle of the picture, set on a slight diagonal and viewed somewhat from above. His kneeling form takes on a trapezoid shape, with one arm stretched to the outer edge of the painting and his gaze looking in the opposite direction. Across the foreground sprawls his symbol, a great lion whose body and tail make a double spiral across the base of the picture space. The other remarkable feature is the sketchy landscape of craggy rocks against which the figure is silhouetted.

The daring display of figure compositon, the landscape elements and personal drama were to reappear in the great unfinished masterpiece, the Adoration of the Magi, a commission from the Monks of St Donato a Scopeto. It is a very complex composition about 250cm square. For it Leonardo did numerous drawings and preapratory studies, including a detailed one in linear perspective of the ruined Classical architecture which makes part of the backdrop to the scene. But in 1482 Leonardo went off to Milan at the behest of Lorenzo de’ Medici in order to win favour with Ludovico il Moro and the painting was abandoned.

The third important work of this period is the Madonna of the Rocks which was commissioned in Milan for the Confraternity of the Immacculate Conception. The painting, to be done with the assistance of the de Predis brothers was to fill a large complex altarpiece, already constructed.

Leonardo chose to paint an apocryphal moment of the infancy of Christ when the Infant John the Baptist, in protection of an angel, met the Holy Family on the road to Egypt. In this scene, as painted by Leonardo, John recognises and worships Jesus as the Christ. The painting demonstrates an eerie beauty as the graceful figures kneel in adoration around the infant Christ in a wild and rocky lanscape of tumbling rock and whirling water.

While the painting is quite large, about 200 x 120 cms, it is nowhere as complex as the painting ordered by the monks of St Donato, having only four figures rather than about 50 and a rocky landscape rather than architectural details. The painting was eventually finished; in fact, two versionns of the painting were finished, one which remained at the chapel of the Confraternity and the other which Leonardo carried away to France. But the Brothers did not get their painting, or the de Predis their payment until both were long over due.

Paintings of the 1490s

The most famous painting the 1490s is Last Supper, also painted in Milan. The painting represents the last meal shared by Jesus with his desciples before his capture and death. It shows, specifically the moment when Jesus has said “one of you will betray me.”

Leonardo tells the story of the consternation that this statement caused to the twelve followers of Jesus. Vasari[5] describes in detail how he worked on it, how some days he would paint like fury, how other days he would spend hours just looking at it, and how he walked the streets of the city looking for the face of Judas, the traitor.

When finished, the painting was acclaimed as a masterpiece of design and characterisation. But its artist was also denounced for the fact that it was no sooner finished than it began to fall off the wall. Leonardo, instead of using the reliable technique of fresco had experimented with different paint-binding agents, which were subject to mold and to flaking. Despite this, the painting has remained one of the most reproduced works of art, countless copies being made in every medium from carpets to cameos.

Paintings of the 1500s

Among the works created by Leonardo in the 1500s are the Mona Lisa and the Virgin and Child with St. Anne. This composition again picks up the theme of figures in a landscape. It harks back to the St Jerome picture with the figure set at an oblique angle. The thing that makes this painting unusual is that there are two obliquely-set figures, superimposed, because Mary, is seated on the knee of her mother, St Anne, and leaning forward to support the Christ Child as he plays (rather roughly) with a lamb, the sign of his own impending sacrifice. In the composition of this painting, Leonardo is showing trends which would be adopted in particular by the Venetian painters, Titian and Tintoretto as well as by Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo and Correggio.

Section references for Leonardo's painting: della Chiesa[15], Wasserman[16].

Leonardo's drawings

Leonardo was not a prolific painter, but he was a most prolific draftsman, keeping journals full of small sketches and detailed drawings recording all manner of things that took his attention. As well as the journals there exist many studies for paintings, some of which can be identified as preparatory to particular works such as The Adoration of the Magi, The Virgin of the Rocks' and The Last Supper. His earliest dated drawing is a Landscape of the Arno Valley, 1473, which shows the river, the mountains, Montelupo Castle and the farmlands beyond it in great detail.

Among his famous drawings are the Vitruvian Man, a study of the proportions of the human body, the Head of an Angel, for The Virgin of the Rocks in the Louvre, a botanical study of Star of Bethlehem and a large drawing (160x100 cms) in black chalk on coloured paper of the The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist in the National Gallery, London. This drawing employs the subtle sfumato technique of shading, in the manner of the Mona Lisa. It is thought that Leonardo never made a painting from it, the closest similarity being to The Virgin and Child with St. Anne in the Louvre.

Other drawings of interest include numerous studies of facial deformaties which are frequently referred to as "caricatures", while close examination of the skeletal proportions indicates that the majority are based directly on live models. There are numerous studies of the beautiful young man, Salaino, with his rare and much admired facial feature, the so-called "Grecian profile".[17] He is often depicted in fancy-dress costume. Leonardo is known to have designed sets for pageants with which these may be associated. Other, often meticulous, drawings show studies of drapery. A marked development in Leornardo's ability to draw drapery occurred in his early works. Another often-reproduced drawing is a macabre sketch that was done by Leonardo in Florence in 1479 showing the body of Bernado Baroncelli, hanged in connection with the murder of Giuliano, brother of Lorenzo de'Medici, in the Pazzi Conspiracy. With dispassionate integrity Leonardo has registered in neat mirror writing the colours of the robes that Baroncelli was wearing when he died.

Section reference: Popham[18]

Main articles on individual paintings

- The Baptism of Christ (1472–1475) – Uffizi, Florence, Italy (from Verrocchio's workshop; angel on the left-hand side is generally agreed to be the earliest surviving painted work by Leonardo)

- Annunciation (1475–1480) – Uffizi, Florence, Italy

- Ginevra de' Benci (c. 1475) – National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States

- The Benois Madonna (1478–1480) – Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

- Adoration of the Magi (1481) – Uffizi, Florence, Italy

- Virgin of the Rocks two versions, (1483–86) and (possibly 1508)– Louvre, Paris, and National Gallery, London, UK.

- Lady with an Ermine (1488–90) – Czartoryski Museum, Kraków, Poland

- Portrait of a Musician (c. 1490) – Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan, Italy

- Madonna Litta (1490–91) – Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

- La belle Ferronière (1495–1498) – Louvre, Paris, France — attribution to Leonardo is disputed

- Last Supper (1498) – Convent of Sta. Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy

- The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist (c. 1499–1500) – National Gallery, London, UK

- Madonna of the Yarnwinder 1501 (original now lost)

- Mona Lisa or La Gioconda (1503-1505/1507) – Louvre, Paris, France

- Leda and the Swan (1508) - (Only copies survive — best-known example in Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy)

- The Virgin and Child with St. Anne (c. 1510) – Louvre, Paris, France

- St. John the Baptist (c. 1514) – Louvre, Paris, France

- Bacchus (or St. John in the Wilderness) (1515) – Louvre, Paris, France

- The Holy Infants Embracing c. 1486-90 private collection

Leonardo as observer, scientist and inventor

Journals

Renaissance humanism saw no mutually exclusive polarities between the sciences and the arts, and Leonardo's studies in science and engineering are as impressive and innovative as his artistic work, recorded in notebooks comprising some 13,000 pages of notes and drawings, which fuse art and natural philosophy (the forerunner of modern science). These notes were made and maintained daily throughout Leonardo's life and travels, as he made continual observations of the world around him.

The journals are written mostly in mirror-image cursive, the reason probably his left-handedness which makes it difficult to push a quill pen from left to right across a page.

Some of the notes and drawings simply record what he has seen, some are detailed studies and others are plans for artworks and inventions. They display an enormous range of interests and preoccupations, some as mundane as lists of groceries and people who owed him money and some as intriguing as designs for wings and shoes for walking on water. There are compositions for paintings, studies of details and drapery, studies of faces and emotions, of animals, babies, dissections, plant studies, rock formations, whirl pools, war machines, helicopters and architecture.

These notebooks—originally loose papers of different types and sizes, distributed by friends after his death—have found their way into major collections such as the Louvre, the Biblioteca Nacional de España, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, and the Victoria and Albert Museum and British Library in London. The British Library has put a selection from its notebook (BL Arundel MS 263) on the web in the Turning the Pages section. [4] The Codex Leicester is the only major scientific work of Leonardo's in private hands. It is owned by Bill Gates, and is displayed once a year in different cities around the world.

Why Leonardo did not publish or otherwise distribute the contents of his notebooks remains a mystery to those who believe that Leonardo wanted to make his observations public knowledge. Technological historian Lewis Mumford suggests that Leonardo kept notebooks as a private journal, intentionally censoring his work from those who might irresponsibly use it (the tank, for instance). They remained obscure until the 19th century, and were not directly of value to the development of science and technology.

In January 2005, researchers discovered what some believe to be a hidden laboratory used by Leonardo da Vinci for studies of flight and other pioneering scientific work in previously sealed rooms at a monastery next to the Basilica of the Santissima Annunziata, in the heart of Florence.[5]

Scientific studies

Leonardo's approach to science was an observational one: he tried to understand a phenomenon by describing and depicting it in utmost detail, and did not emphasize experiments or theoretical explanation. Since he lacked formal education in Latin and mathematics, contemporary scholars mostly ignored Leonardo the scientist, although he did teach himself Latin. In the 1490's he studied mathematics under Luca Pacioli and prepared a series of drawings of regular solids in a skeletal form to be engraved as plates for Pacioli's book Divina Proportione, published in 1509.

It has also been said that he was planning a series of treatises to be published on a variety of subjects though none survives; it appears he did complete a coherent treatise on anatomy, which was observed during a visit by Cardinal Louis D'Aragon's secretary in 1517. [19]

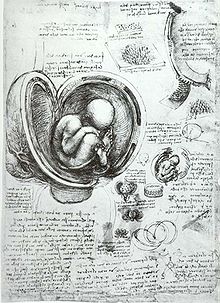

Anatomy

Leonardo formal training in the anatomy of the human body began with his apprenticeship to Andrea del Verrocchio, his teacher insisting that all his pupils learn anatomy. As an artist, he quickly became master of topographic anatomy, drawing many studies of muscles, tendons and other visible anatomical features.

As a successful as an artist, he was given permission to dissect human corpses at the hospital Santa Maria Nuova in Florence and later at hospitals in Milan and Rome. From 1510 to 1511 he collaborated in his studies with the doctor Marcantonio della Torre and together they prepared a theoretical work on anatomy for which Leonardo made more than 200 drawings. It was published only in 1680 (161 years after his death) under the heading Treatise on painting.

Leonardo drew are many studies of the human skeleton and its parts, as well as muscles and sinews, the heart and vascular system, reproductive system, and other internal organs. He made one of the first scientific drawings of a fetus in utero.

He also studied and drew the anatomy of many other animals as well. He dissected cows, birds, monkeys, bears, and frogs, comparing in his drawings their anatomical structure with that of humans. He also made a number of studies of horses.

As an artist, Leonardo closely observed and recorded the effects of age and of human emotion on the physiology, studying in particular the effects of rage. He also drew many models among those who had significant facial deformities or signs of illness.

Engineering and inventions

Fascinated by the phenomenon of flight, Leonardo produced detailed studies of the flight of birds, and plans for several flying machines, including a helicopter powered by four men (which would not have worked since the body of the craft would have rotated) and a light hang glider which could have flown.[20] On January 3, 1496 he unsuccessfully tested a flying machine he had constructed.

In 1502, Leonardo produced a drawing of a single span 720-foot (240 m) bridge as part of a civil engineering project for Ottoman Sultan Beyazid II of Istanbul. The bridge was intended to span an inlet at the mouth of the Bosphorus known as the Golden Horn. Beyazid did not pursue the project, because he believed that such a construction was impossible. Leonardo's vision was resurrected in 2001 when a smaller bridge based on his design was constructed in Norway. On 17 May 2006, the Turkish government decided to construct Leonardo's bridge to span the Golden Horn.[citation needed]

Leonardo, the "Legend"

Within Leonardo's own lifetime his fame was such that the King of France carried him away like a trophy, supported him in his old age and held him in his arms as he died. Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists written about thirty years after Leonardo's death, described him as having talents that "transcended nature".

The interest in Leonardo has never slackened. The crowds still queue to see his most famous artworks, T-shirts bear his most famous drawing and writers, like Vasari, continue to marvel at his genius and speculate about his private life and, particularly, about what one so intelligent actually believed in.

Vasari's "Lives"

Johannite heresy

It has been the subject of much speculation whether Leonardo was an orthodox Christian or whether he was a heretic. Many conspiracy theorists believe that he was "infected" with the Johannite heresy, that is, he regarded not Jesus Christ but John the Baptist as the real Christ. This subject has also been the source for many best-selling books in recent times. [citation needed]

Cultural depictions

With the genius and legacy of Leonardo da Vinci having captivated authors and scholars generations after his death, many examples of "da Vinci fiction" can be found in culture and literature. As of 2006, the most prominent example is Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code (2003), which is concerned with Leonardo's role as a supposed member of a secret society called the Priory of Sion.

See also

- Leonardo Da Vinci International Airport near Rome

- Leonardo da Vinci Art Institute, Cairo

- Luca Pacioli

- List of painters

- List of famous left-handed people

- List of Italian painters

- List of famous Italians

- Polymath

- Aerial perspective

- Roger Bacon

References and notes

- ^ This drawing in red chalk is widely (though not universally) accepted as an original self-portrait. The main reason for hesitation in accepting it as a portrait of Leonardo is that the subject is apparently of a greater age than Leonardo ever achieved. But it is possible that he drew this picture of himself deliberately aged, specifically for Raphael's portrait of him in the School of Athens.

- ^ Modern scientific approaches to metallurgy and engineering were only in their infancy during the Renaissance.

- ^ Birth recorded in the diary of his paternal Grandfather, Ser Antonio.

- ^ a b Liana Bortolon, The Life and Times of Leonardo, Paul Hamlyn, London, 1967, ISBN

- ^ a b c d Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, 1568; this edition Penguin Classics, trans. George Bull 1965, ISBN 0-14-044-164-6

- ^ a b c Angela Ottino della Chiesa, Leonardo da Vinci, Penguin Classics of World Art series, ISBN 0-14-00-8649-8

- ^ Donatello's David

- ^ Andrew Martindale, The Rise of the Artist, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-5000-56006-4

- ^ Gene A. Brucker, Renaissance Florence, 1969, Wiley and Sons, ISBN 0-471-11370-0

- ^ Ilan Rachum, The Renaissance, an Illustrated Encyclopedia, Octopus, ISBN 0-7064-0857-8

- ^ D'Oggione made contemporary copies of the Last Supper fresco

- ^ Oreno website (Italian)

- ^ Leonardo da Vinci's relationships

- ^ Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships epigraph, p. 148 & N120 p.298

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Chiesawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Jack Wasserman, Leonardo da Vinci, 1975 Abrams, ISBN 0-8109-0262-1

- ^ The "Grecian profile" has a continuous straight line from forehead to nose-tip, the bridge of the nose being exceptionally high. It is a feature of many Classical Greek statues.

- ^ A. E. Popham, The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, 1975 edition, Jonathan Cape, ISBN 0-224-60462-7

- ^ O'Malley & Saunders, Leonardo on the Human Body, 1982, Dover Publications New York

- ^ The U.S. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), aired in October 2005, a television programme called "Leonardo's Dream Machines", about the building and successful flight of a glider based on Leonardo's design

- History of Aerodynamics, John David Anderson, page 19. ISBN 0-521-66955-3

- Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists

- Birth of Modern Science, Paolo Rossi, page 33. ISBN 0-631-22711-3

- Emperor Charles V, Impresario of War, James D Tracy, page 41. ISBN 0-521-81431-6

- Algebra in Ancient and Modern Times, V S Varadarajan, page 58. ISBN 0-8218-0989-X

- ArtNews article about current studies into Leonardo's life and worksU.S.A

Further reading

- Jean Paul Richter (1970). The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Dover. ISBN 0-486-22572-0 and ISBN 0-486-22573-9 (paperback). 2 volumes. A reprint of the original 1883 edition.

- Frank Zollner & Johannes Nathan (2003). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings. Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-1734-1 (hardback).

- Fred Bérence (1965). Léonard de Vinci, L'homme et son oeuvre. Somogy. Dépot légal 4° trimestre 1965.

- Charles Nicholl (2005). Leonardo da Vinci, The Flights of the mind. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-029681-6.

- Simona Cremante (2005). Leonardo da Vinci: Artist, Scientist, Inventor. Giunti. ISBN 88-09-03891-6 (hardback).

- John N. Lupia, "The Secret Revealed: How to Look at Italian Renaissance Painting," Medieval and Renaissance Times, Vol. 1, no. 2 (Summer, 1994): 6-17. (ISSN 1075–2110)

- Sherwin B. Nuland, "Leonardo Da Vinci." 176 P. Phoenix Press. 2001. ISBN 0-7538-1269-X

- Michael H. Hart (1992). The 100. Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8065-1350-0 (paperback).

External links

- Sketches of a Renaissance Man

- Mona Lisa - A Scientific Examination

- Leonardo da Vinci: Experience, Experiment, Design

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Manifest "Salviamo Leonardo" [6]

- Review: 2003 drawings exhibition, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York [7]

- Leonardo da Vinci "Life and Works" in "A World History of Art"

- Works by Leonardo da Vinci at Project Gutenberg

- Leonardo da Vinci by Maurice Walter Brockwell' at Project Gutenberg

- Complete text & images of Richter's translation of the Notebooks

- Vasari: Life of Leonardo: in Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

- Leonardo's Paintings and Drawings (flash format

- Leonardo's Testament

- Leonardo da Vinci, biography from the Italian National Museum of Science and Technology

- Some digitized notebook pages with explanations from the British Library (Macromedia Shockwave format)

- English translation of the Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci

- BBC Leonardo homepage

- Web Gallery of Leonardo Paintings

- Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci

- Leonardo da Vinci : The Leicester Codex

- Leonardo's Letter to Ludovico Sforza

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry on Leonardo da Vinci

- Da Vinci Decoded Article from The Guardian

- Guide to London Exhibition of Leonardo Drawings

- Dowload site for audio guide (mp3, 17 mins) to London Exhibition of Leonardo Drawings

- Short Biography of Leonardo

- Leonardo, the city of Vinci and Anchiano

- Secrets of Leonardo's Machine Tools: An MP3 audio lecture on da Vinci (10/11/2003) -20 MB

- Review of Experience, Experiment and Design Exhibition at London's Victoria and Albert Museum

- Leonardo`s Invincible Smile Template:Es icon

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Italian painters

- Italian anatomists

- Italian civil engineers

- Dynamicists

- Mathematics and culture

- Military engineers

- People prosecuted under anti-homosexuality laws

- Renaissance architects

- Renaissance artists

- Renaissance painters

- Italian autodidacts

- Italian vegetarians

- Tuscan painters

- History of anatomy

- Artists

- 1452 births

- 1519 deaths