Climate of India

The climate of India is difficult to generalize due to the country's vast geographic scale and varied topography. For example, various microclimates prevailing within broader temperate and subalpine climatic zones in and near mountainous regions, such as in the state of Jammu and Kashmir in the extreme north, differ markedly from the hot and tropical plains of the south, such as the Deccan Plateau.

India's climate is strongly influenced by the Himalayas and the Thar Desert. The Himalayas ensure that, by acting as a barrier to the cold north winds from Central Asia, northern India is warm or mildly cool during winter and hot during summer. Thus, although the Tropic of Cancer (the dividing line between the tropical and sub-tropical regions) passes almost through the middle of India, India as a whole is considered to be a tropical country.

India experiences three distinct seasons: summer, which lasts from March to June; a monsoon (rainy) season, lasting from June to October; and winter, from November to March. Monsoonal conditions in India are unstable and vary widely, because of differences in how clouds ascending towards the high Himalaya reach the local dew point; upon doing so, torrents of rainfall descend upon the lands below them.

Climatology

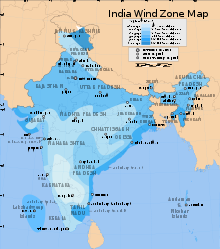

|

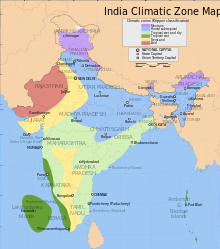

|

India's climate varies from tropical in the south to more temperate in the Himalayan north, where elevated regions receive sustained winter snowfall. Its climate is strongly influenced by the Himalayas and the Thar Desert, as India's northern and north-eastern states are partially situated in the mountains. The Himalayas, along with the Hindu Kush mountains in Pakistan, prevent cold Central Asian katabatic winds from blowing in. This keeps the bulk of the Indian subcontinent warmer than most locations at similar latitudes. Simultaneously, the Thar Desert plays a role in attracting moisture-laden summer monsoon winds that, between June and September, provide the majority of India's rainfall.

Most of India experiences three distinct seasons:

- Summer, typically lasting from March to June (April to July in northwestern India). The hottest month for western and southern regions is April; for northern regions, May is the hottest month. Temperatures average around 32–40 °C (90–104 °F) in most of the interior.

- Monsoon or rainy season, lasting from June to October. South India typically receives more precipitation. Monsoonal rains begin to recede from North India at the beginning of October. In northwestern India, October and November are usually cloudless.

- Winter, from November to March. The year's coldest months are December and January, when temperatures average around 10–15 °C (50–59 °F) in the northwest; temperatures rise as one proceeds towards the equator, peaking around 20–25 °C (68–77 °F) in mainland India's southeast.

The Himalayan states, being more temperate, experience an additional two seasons: autumn and spring. Traditionally, Indians note six seasons, each about two months long. These are the spring (Sanskrit: vasant), summer (greeshm), monsoons (varsha), early autumn (sharad), late autumn (hemant), and winter (shishir). These are based on the astronomical division of the twelve months into six parts. The ancient Hindu calendar also reflects these seasons in its arrangment of months.

Climatic regions

|

India is home to an extraordinary range of climatic regions; four major climatic groupings predominate; these can be further subdivided into seven climatic subtypes according to the Köppen climate classification system.

Tropical wet

A tropical rainy climate covers regions experiencing persistent high temperatures, which normally do not fall below 18 °C (64 °F) even in the coolest months. India hosts two climatic subtypes that fall under this group. The most humid it the tropical monsoon rain forest climate that covers a strip of southwestern lowlands abutting the Malabar Coast, the Western Ghats, and southern Assam. Characterized by moderate to high year-round temperatures, even in the foothills, its rainfall is seasonal but heavy—typically above 2,000 millimetres (79 in) per year. Most rainfall occurs between May and November; this is adequate for the maintenance lush forests and other vegetation throughout the remainder of the year. December to March are the driest months, when days with precipitation are rare. The heavy monsoon rains are responsible for the extremely biodiverse tropical wet forests of these regions.

However, most of India's land falling into this group is defined by a tropical wet and dry climate subtype. Significantly drier than tropical wet zones, it prevails over most of inland peninsular India except for a semi-arid rain shadow east of the Western Ghats. Winter and early summer are long, dry periods with temperature averaging above 18 °C (64 °F). Summer is exceptionally hot; temperatures in low-lying areas may exceed 45 °C (113 °F) during May. The rainy season lasts from June to September; annual rainfall averages between 750–1500 millimeters (30–59 in). Only Tamil Nadu receives substantial rainfall during the winter months between October and December.

Tropical wet and dry

A tropical wet and dry climate dominates regions where the rate of water's evapotranspiration is higher than the rate of moisture received through precipitation; it is subdivided into three climate types. The first, a tropical semi-arid steppe climate, predominates over a long stretch of land situated to the south of Tropic of Cancer and east of the Western Ghats and the Cardamom Hills. The region includes Karnataka, inland Tamil Nadu, western Andhra Pradesh, and central Maharashtra. This region is a famine-prone zone with very unreliable rainfall, which varies between 400–750 millimeters (16–30 in) annually. North of the Krishna River, the summer monsoon is responsible for most rainfall; to the south, significant rainfall also occurs in October and November. In December, the coldest month, temperatures still average around 20–24°C (68–75 °F). The months between March to May are hot and dry; mean monthly temperatures hover around 320 millimetres (13 in). The vegetation mostly comprises grasses with a few scattered trees due to the rainfall. Hence, without artificial irrigation, this region is not suitable for permanent agriculture.

Most of western Rajasthan falls under a tropical and sub-tropical climate type characterized by scanty rainfall. Cloudbursts are responsible for nearly the entire total of annual precipitation in this region, which totals less than 300 millimetres (12 in). Such bursts happen when monsoon winds sweep into the region during July, August, and September. The rainfall is very erratic; regions experiencing rainfall one year may not see precipitation for the next couple of years or so. The summer months of May and June are exceptionally hot; mean monthly temperatures in the region hover around 35 °C (95 °F), with daily maximums occasionally topping 50 °C (122 °F). During winters, ambient temperatures can drop below freezing in some areas due to waves of cold air from Central Asia. There is a large diurnal range of about 14 °C (57 °F) during summer; this widens by several degrees during winter. This extreme climate accounts for it being one of the most sparsely populated regions in India.

The region towards the east of the tropical desert running from Punjab and Haryana to Kathiawar experiences a tropical and sub-tropical steppe climate. This zone, which is a transitional climate separating tropical desert from humid sub-tropical lands, experiences temperatures which are less extreme than the desert climate. Average annual rainfall is 30–65 cm, but is very unreliable; as in much of the rest of India, the summer monsoon season accounts for most precipitation. Daily maximum temperatures during summer can rise to around 40 °C (104 °F). The resulting natural vegetation typically comprises short, coarse grasses. Crops such as jowar and bajra are also cultivated.

Subtropical humid

Most of Northeast India and much of North India are subject to a humid sub-tropical climate. Though they experience hot summers, temperatures during the coldest months may fall as low as 0 °C (32 °F). Due to ample monsoon rains, India has only one subtype of this climate, Cfa. In most of this region, there is very little precipiation during the winter, owing to powerful anticyclonic and katabatic (downward-flowing) winds from Central Asia. Due to the region's proximity to the Himalayas, it experiences elevated prevailing wind speeds, again from the influence of Central Asian katabatic movements.

Montane

India's northernmost fringes are subject to a montane climate group. In the Himalayas, temperatures falls by 0.6 °C (33.1 °F) for every 100 metres (328 ft) rise in altitude, giving rise to climates ranging from nearly tropical in the foothills to tundra above the snow line. Sharp temperature contrasts between sunny and shady slopes, high diurnal temperature variability, temperature inversions, and altitude-dependent variability in rainfall are also prevalent. The northern side of the western Himalayas, also known as the trans-Himalayan belt, is a region of arid, frigid, and generally wind-blown wastes. Most precipitation comes as snowfall during the late winter and spring months.

Areas to the south of the Himalayas are protected from cold winter winds coming in from interior of Asia. The leeward side of the mountains receive less rain while the well-exposed slopes get heavy rainfall. Areas situated at altitudes of 1070–2290 m receive the heaviest rainfall, which decreases rapidly as one climbs above 2,290 metres (7,513 ft). The Himalayas experience the heaviest snowfall from December to February at altitudes above 1,500 metres (4,921 ft).

Seasons

Winter

Once the monsoons subside, average temperatures gradually fall across India after September. As the vertical rays of the sun move south of the equator, the country experiences cool weather with temperatures decreasing by about 0.6°C for every 1° latitude moved north. December and January are typically the coldest months, with mean temperatures of 10 to 15°C in the northwest and the Himalayan region. The mean temperatures increase towards east and south, where it is between 20 to 25°C.

In northwest India, October and November are cloudless. This leads to a high diurnal range of temperatures during these months. It ranges between 16 to 20°C in northwest India as well as across much of Deccan Plateau, and 12 to 14°C in the coastal strip. The entire Himalayan range, from Kashmir to Arunachal Pradesh in northeast India, receives significant snowfall. However, the rest of north India, including the Indo-Gangetic Plain, does not receive snow. However, the minimum temperature in the plains falls below freezing occasionally, though not for more than a couple of days in December and January. Highs in Delhi range between 16 °C (61 °F) to 21 °C (70 °F). Nighttime temperatures range between 2 to 8°C. Further north in the Punjab region the low does fall below freezing in the plains: to around −6 °C (21 °F) in Amritsar. Frost sometimes occurs, but the hallmark of the season is the notorious fog, which frequently disrupts daily life; fog grows thick enough to substantially hinder visibility and disrupt air travel an average of 15–20 days annually.[1]

Northern India does receive some rainfall due to the "Western Disturbances", or warm, moist winds originating in the Mediterranean Sea. As these disturbances travel eastwards, their passage is steadily blocked by the Himalayas; unable to ascend their crest, they drop their rain over northern India instead.

Eastern India has a much milder climate. It has mild days and cool nights. Highs range from 23°C in Patna to 26 °C (79 °F) in Kolkata (Calcutta); lows average from 8 °C (46 °F) in Patna to 14 °C (57 °F) in Kolkata. The cold winds over the Brahmaputra River lower the temperatures.

In South India, the Maharashtrian hinterland, Madhya Pradesh, and parts of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, somewhat cooler weather prevails. Minimum temperatures in western Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh hover around 10 °C (50 °F); they correspondingly reach about 16 °C (61 °F) in the southern Deccan Plateau. Coastal areas and low-level interior tracts are warm with highs of 30 °C (86 °F) and lows of 21 °C (70 °F). The Nilgiri range is exceptional; there, lows can fall below the freezing point.

Summer

Summer in northwestern India lasts from April to July, and in the rest of the country from March to June. The temperatures in the north rise as the vertical rays of the Sun reach the Tropic of Cancer. The hottest month for the western and southern regions of the country is April, while for the northern regions it is May. By May, most of interior India experiences mean temperatures over 32°C and maximum temperatures exceeding 40 °C (104 °F). Temperatures of 49 °C (120 °F) and higher have been recorded in parts of India during this season. In cooler regions, hailstones may fall. Near the coast the temperature hovers around 36 °C (97 °F), and the proximity of the sea increases the level of humidity. In southern India, the temperatures are higher on the east coast by a few degrees compared to the west coast.

Altitude affects the temperature to a large extent, with the higher parts of the Deccan Plateau and hills being relatively cooler. The Himalayan and Nilgiri hill stations, with average maximum temperates of around 25 °C (77 °F), offer some respite from the heat.

Monsoon

The southwest summer monsoon, borne on maritime winds predominating from the southwest, bring much-anticipated relief from the scorching heat and parched landscape of the summer months. These inflows of moist air masses are ultimately the result of a northward shift of the local jet stream, which itself results from rising summer temperatures over Tibet and the Indian subcontinent. The void left by the jet stream, which switches from a route just south of the Himalayas to one tracking north of Tibet, then attracts the aforementioned tropical air masses, which have been moistened by the Indian Ocean.[2]

The rains bring down average daily temperatures and make the countryside lush and green. The monsoons are intricately linked to the Indian economy: since agriculture employs 600 million Indians and comprises almost 20% of the national GDP,[3] a good monsoon often correlates with a booming economy, while weak or failed monsoons (droughts) result in widespread agricultural losses, substantially slowing overall economic growth.[4][5][6] The rains also recharge groundwater tables and reinvigorate rivers and lakes.

The southwest summer monsoon, which usually breaks over the Indian mainland beginning around 1 June,[7] supplies over 80% of India's annual rainfall. There are two branches to the monsoon: the Bay of Bengal branch; and the Arabian Sea branch, which extends to the low pressure area over the Thar Desert in Rajasthan. The Arabian Sea branch is roughly three times stronger than the Bay of Bengal branch. A related phenomenon, the northeast (or "retreating") monsoon period is not a true season as such. Many textbooks however, refer to this as a separate season. Depending on location, this period lasts from October and November, after the southwest monsoon has peaked. Less and less precipitation occurs, and vegetation begins to dry out. In most parts of India, this period marks the transition from wet to dry seasonal conditions. Average daily maximum temperatures range between 28°C and 34°C.

In India, the monsoon appears by around the end of May. It begins around 29 May, hitting the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. It then strikes the mainland around the Malabar Coast of Kerala by 1 June. By 9 June, it reaches Mumbai; it appears over Delhi by 29 June. The Bay of Bengal monsoon moves in a northwest direction whereas the Arabian Sea monsoon moves northeast. By the first week of July, the entire country experiences rain. During the season, South India usually receives more rainfall than North India. However, Northeast India receives the most precipitation from the monsoon. Indeed, Cherrapunji, in Meghalaya, is officially the world's wettest place, receiving 10,000 millimetres (394 in) of rainfall annually. The monsoon clouds begin to retreat from North India by the last week of August. It withdraws from Mumbai by 5 October; after the air over India cools further during September, the monsoon gradually departs India altogether, usually by the end of November.[2]

Natural disasters

India is prone to several types of climate-related natural disasters that are responsible for massive losses of life and property. These include droughts; flash floods, and widespread and destructive flooding from monsoonal rains; severe cyclones; landslides and avalanches brought on by torrential rains; and snowstorms. Other events include frequent summer dust storms, which usually track from north to south and cause extensive property damage in northern India.[8] These storms bring with them large amounts of dust from arid regions. Hail is also common in parts of India, and cause severe damage to standing crops like rice and wheat.

Floods and landslides

Floods are the most common natural disaster in India. When the monsoon season arrives, the heavy rainfall that follows the dry winter months may cause rivers to distend their banks, often flooding the surrounding areas. One example is the Brahmaputra River is prone to perennial flooding during the monsoon season. But while the seasonal floods are often responsible for killing thousands and displacing millions, they also are relied upon by rice paddy farmers for irrigation. Nevertheless, excess, erratic, or untimely monsoon rainfall may still wash away or otherwise ruin crops.[9][10] With the exception of a few states, almost all of India is prone to flooding.

Landslides are common in the Lower Himalaya, owing to labile rock formations due to the young age of the hills. Deforestation, resulting from both rising population pressure and tourism-related and other development, has been been implicated as a major factor in exacerbating the extent of landslides, since tree cover impedes the flow of monsoon rains down hillsides.[11] Parts of the Western Ghats also suffer from low-intensity landslides. Avalanches occur in Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Sikkim.

Cyclones

Tropical cyclones, severe storms spun off from the Intertropical Convergence Zone, affect thousands of Indians living in coastal regions annually. Tropical cyclogenesis is particularly common in the northern reaches of the Indian Ocean in and around the Bay of Bengal. Cyclones bring with them heavy rains, storm surges, and winds that often cut affected areas off from relief and supplies. The cyclone season in the North Indian Ocean Basin runs from April to December, with peak activity falling between May and November.[12] Each year, an average of eight storms with sustained wind speeds greater than 63 km:h[convert: unknown unit] form; of these, around two strengthen into true tropical cyclones, which have sustained gusts greater than 117 km:h[convert: unknown unit]. On average, a major (Category 3 or higher) cyclone develops every other year.[13][14]

Due to very active weather systems and intense heating in the Bay of Bengal, cyclones form during this season. Many powerful cyclones, including the 1737 Calcutta cyclone, the 1970 Bhola cyclone, the 1991 Bangladesh cyclone, and Cyclone 05B have led to widespread devastation along parts of the eastern coast of India and neighboring Bangladesh. Many deaths and widespread destruction of property are reported every year in exposed coastal states like Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal. On the more placid west coast and Arabian Sea, cyclones are rare, mainly affecting Gujarat and, to an even lesser extent, Kerala.

One notable example is Cyclone 05B, a supercyclone that struck Orissa on 29 October 1999; in terms of damage and loss of life, it was the worst in more than a quarter century. With peak winds of 160 mi:h[convert: unknown unit], the equivalent of a Category 5 hurricane.[15] Around 1.67 million people homeless;[16] another 19.5 million people were affected by the cyclone to some degree.[16] A total of 9,803 people officially died from the storm,[15] though unofficial estimates place the death toll at over 10,000.[16]

Droughts

Indian agriculture is heavily dependent on the monsoon as a source of water. In some parts of India, the failure of the monsoons results in water deficiency in the region causing extensive crop losses. Drought-prone regions include southern Maharashtra, northern Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, Gujarat, and Rajasthan. In the past, monsoon failures have causing great damage to Indian agricultural yields, at times leading to famines. Notable examples include the Bengal famine of 1770, in which up to one third of the population in the affected area died; the 1876–1877 famine, in which over five million died; the 1899 famine, in which over 4.5 million died; and the Bengal famine of 1943.[17][18]

Many such episodes of drought-related famine correlate with occurences of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).[19] El Niño-related droughts have also been implicated in periodic declines in Indian agricultural output.[20] Nevertheless, ENSO events that have coincided with abnormally high sea surfaces temperatures in the Indian Ocean—in one instance during 1997 and 1998 by up to 3 °C (5 °F)—have resulted in increased oceanic evaporation, resulting in unusually wet weather across India; such anomalies have occurred during a sustained warm spell that began in the 1990s.[21] A related phenomenon is that, instead of the usual high pressure air mass over the southern Indian Ocean, an ENSO-related oceanic low pressure convergence center forms; it then continually pulls dry air from Central Asia, dessicating India during what should have been monsoon season. This reversed air flow thus results in India's sporadic droughts.[22]

Extremes

The highest temperature recorded in India was 50.6 °C (123 °F) in Alwar in 1955. The lowest was −45 °C (−49 °F) in Kashmir. Recently, claims have been made of temperatures touching 55 °C (131 °F) in Orissa;[1] these have been met with some scepticism by the Indian Meteorological Department, which has questioned the methods used in recording such data.

The average annual precipitation of 11,871 millimetres (467 in) in the village of Mawsynram, in the hilly northeastern state of Meghalaya, is the highest recorded in Asia, and possibly on Earth.[23] The village, which sits at an elevation of 1,401 metres (4,596 ft), benefits from its proximity to the Himalayas. However, since the village of Cherrapunji, 5 kilometres (3 mi) to the east, is the nearest town to host a meteorological office (none has ever existed in Mawsynram), it is officially credited as being the world's wettest place.[24]

Climate change

Several aspects of climate change, including steady sea level rise, increased cyclonic activity, and changes in ambient temperature and precipitation patterns, have impacted or are projected to impact India. For example, ongoing sea level rises have submerged several low-lying islands in the Sundarbans, displacing thousands of people.[25] Furthermore, as temperatures steadily rise on the Tibetan Plateau and Himalayan glaciers retreat, the long-term flow of the Brahmaputra River, upon which hundreds of thousands of farmers depend, could be jeopardized. In the short term, increased landslides and flooding are projected to impact such states as Assam.[26] In stark contrast, according to a 2007 World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) report, the Indus River may run dry as a result of the ongoing melting of Himalayan glaciers.[27]

The Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research has reported that, if the predictions relating to global warming made by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change come to fruition, climate-related factors could cause India's GDP to decline by up to 9%; contributing to this would be shifting growing seasons for major crops such as rice, production of which could fall by 40%. Around 7.1 million people are projected to be displaced due to, among other factors, submersion of parts of Mumbai and Chennai, if global temperatures were to rise by a mere 2 °C (36 °F).[28]

References

- ^ "Air India Reschedules Delhi-London/New York & Frankfurt flights due to Fog". Air India. 17 December 2003. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Burroughs, William J. (1999). The Climate Revealed. Cambridge University Press. pp. p. 138–139. ISBN 0-521-77081-5.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "CIA Factbook: India". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ "The Impacts of the Asian Monsoon". BBC Weather.

- ^ "India's forgotten farmers await monsoon". BBC News. 20 June 2006.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "India records double digit growth". BBC News. 31 March 2004.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Southwest Monsoon: Normal Dates of Onset".

- ^ Balfour, Edward (1976). Encyclopaedia Asiatica: Comprising Indian Subcontinent, Eastern and Southern Asia. Cosmo Publications. pp. p. 995. ISBN 8170203252.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Template:Harvard referenceAllaby 1998, p. 42.

- ^ Allaby 1998, p. 15

- ^ Allaby 1998, p. 26

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: When is hurricane season?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

AOML FAQ G1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What are the average, most, and least tropical cyclones occurring in each basin?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ^ a b "Tropical Cyclone 05B" (PDF). Naval Maritime Forecast Center/Joint Typhoon Warning Center.

- ^ a b c "1999 Supercyclone of Orissa". BAPS Care International. 2005.

- ^ *Template:Harvard reference. pp. 22-23.

- ^ *Template:Harvard reference. Collier 2002, p. 67.

- ^ *Template:Harvard reference. p. 121.

- ^ Caviedes 2001, p. 259.

- ^ Nash 2002, pp. 258–259.

- ^ Caviedes 2001, p. 117.

- ^ "Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation". National Climatic Data Center (NCDC). 9 August 2004. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Giles, Bill. "Deluges". BBC. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- ^ Harrabin, Roger (1 February 2007). "How climate change hits India's poor". BBC News.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|=ignored (help) - ^ Dasgupta, Saibal (3 February 2007). "Warmer Tibet can see Brahmaputra flood Assam". Times of India. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Rivers run towards 'crisis point'". BBC News. 20 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sethi, Nitin (3 February 2007). "Global warming: Mumbai to face the heat". Times of India. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)