Beach (island)

In the Middle Ages and the early modern period, beach denoted a stretch of coast and later an island in the North Frisian Wadden Sea . The most famous place in Strand was the trading place of Rungholt . From the coastal landscape, after several storm surges in the 14th century, the cartographically known island of Strand (also known as Alt-Nordstrand ) emerged. In the Burchardi flood in 1634, the island was finally torn apart. The islands of Nordstrand , Pellworm and Hallig Nordstrandischmoor formed their remains .

Before the first big mandrank

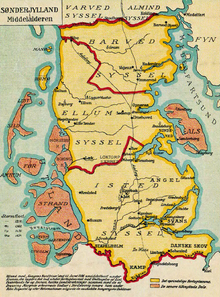

Before the flood disaster in the middle of the 14th century, Strand was part of the Frisian Uthlande, which belonged to the Duchy of Schleswig . Is mentioned for the first time beach as the diocese Schleswig associated provost in two letters of Pope Innocent III. 1198, who criticized the poor roads to the provost. A Rectory also included Foehr , which was then at low tide was still reachable on foot, Amrum and the Halligen . The Waldemar-Erdbuch from 1231 names five Harden , the Beltringharde , the Edomsharde , the Pellwormharde and the Wiriksharde as well as the Lundenbergharde to the southeast . Even then, the fertile arable and pasture land was protected by dykes and the moors were drained by drainage channels .

The little ice age in the 14th century led to cold, wet summers, bad harvests and diseases on the beach. In addition, the sea level rose and several severe storm surges inundated the country and caused permanent damage. The Second Marcellus Flood or Grote Mandränke of 1362 hit the beach hard. Especially in the Edomsharde numerous places, including Rungholt , were destroyed. All wooded areas were lost. The previously only narrow and shallow mudflats between the individual pieces of land were deeply washed away. The Heverstrom dug deep into the land from the south. The island (old) north beach was created from the remains of the land. It was surrounded by a large number of Halligen, in the south near Rungholt Südfall , Nübel and Nieland, to the north of the island a whole chain of unpaved small islets emerged. The Lundenbergharde was cut up and in the following years the greater part was connected to the mainland by dikes. In old maps this area is called South Beach. Only the main town Morsum and two smaller villages remained at Nordstrand.

Between the first and second mandrank

Storm surges

In the centuries that followed, the beach was repeatedly threatened by storm surges. Tax lists of the diocese and the king sometimes show large land losses in the 15th and 16th centuries. Overall, the Schleswig Cathedral Chapter Register recorded the loss of 24 parishes on the beach from 1450 . It was possible to regain individual flooded areas and to restore a sea dike, and several parishes could be rebuilt. After 1456, the Trindermarsch, which had been an island since the Marcellus flood, was diked again. In 1551 the Pellwormharde, which was demolished during the All Saints flood in 1436 , was reconnected to the rest of the beach, giving the island the horseshoe-shaped shape it has on the maps of the 17th century.

But all attempts to reconnect the beach with the mainland or to dam the Rungholt Bay across the Hallig Südfall failed. Instead, the Heverstrom widened the sound, which is why entire villages and churches had to be moved inland again and again. The Halligen remained completely insignificant, and many went down again in later storm surges. The chroniclers counted the All Saints Flood in 1532 as one of the most serious floods in the 16th century , in which eleven dike breaches occurred and 1,500 people drowned.

Political events

In 1350 the first stallion on the beach is attested, a governor appointed by the king. One of the most important Staller families descended from Ingmar, who fought the Wogemänner , whose most famous representative in the 15th century was Laurens Leve from Morsum, who is still present in Schleswig-Holstein's cultural history through his spiritual foundations.

In 1423 three Strander Harden, Pellworm, Beltring and Wiriksharde, together with the Föhrer Harden, Sylt , the Wieding- and the Bökingharde, closed the Siebenharden siege .

In 1528 the Reformation was introduced on Nordstrand, mediated by a number of Stranders who had studied in Wittenberg . The first evangelical preacher was Jürgen Boie at the old church in Pellworm in 1525 . Several schools were established so that the beaches were well educated. By 1600 there were few illiterate people and 14 of the island's 25 or so preachers were born in the country. The Strander were considered stubborn, contentious and only concerned about the well-being of their own family.

When the land was divided in 1544, Nordstrand fell to Duke Johann (Hans) of Schleswig-Holstein-Hadersleben . Duke Hans stayed on the island frequently, personally took care of the improvement of the coastal protection and gave the island its own church ordinance in 1555 and the right to spadeland in 1557 . The Nordstrander Landrecht of 1572 largely took over the norms of Siebenhardenbeliebungs, but abolished the obligation to vengeance . It lasted until 1900. After Duke Hans' death in 1581, Nordstrand fell to his brother Adolf and thus to Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf .

In 1593 the Harden of the Nordstrand landscape were redistributed, with the remnants of the severely shrunken Lundenberg and Wiriksharde being incorporated into the three remaining Harden.

During the Thirty Years War , the Strander sat down against their Duke Friedrich III. and the compulsory billeting of imperial troops for defense. They argued with their high cost for coastal protection, which did not allow an additional burden from foreign soldiers. Although Strand belonged to Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf, the Stranders paid homage to the Danish King Christian IV near Gaikebüll in 1629. With his support, they fought back first an imperial and then a ducal army, but were ultimately defeated by the duke. The maintenance of the dykes suffered from these battles.

Life around 1600

Around 1600 the island was secured by sea dikes all around and divided into several cogs . Matthias Boetius , pastor of the Strander municipality Eversbüll, named the island Strand in 1623, in contrast to Südstrand , the land-made remnants of the Lundenbergharde, Nor (d) strandia . In his little book De Cataclysmo Norstandico , he described them as flat, boggy and treeless. Heather and peat were therefore used as fuel . Wood as a building material had to be imported from afar. The latter meant great difficulties in procuring the amount of wood required for the stack dikes that were common at the time . Even then, with the exception of a few recently diked mounds such as the Amsinckkoog and the large moor in the north of the island , the land was lower than the sea level at high tide . If dike breaches occurred during storm surges , these often had the consequence that the land up to the next central dike was flooded twice a day before the dykes could be repaired. The result was deep flooding and several years of crop failures.

Even so, the beach was considered fertile and prosperous. The majority of the 8610 inhabitants in 1779 households worked in agriculture, either as free farmers or as farm workers. In addition, numerous craftsmen lived on the island, as well as day laborers and servants who were not counted as permanent residents. Boetius' contemporary, the Odenbüller pastor Johannes Petersen (or Peträus) raved about the rich yields of the fertilized bog soils and the fertile clay . Besides the cultivation of grain, ox fattening and dairy farming were important branches of the economy. In addition, salt was extracted from salt peat , which increased the prosperity of the inhabitants, but caused the land within the dikes to sink further. The proceeds were exported from several small ports.

The catastrophe

Situation at the beginning of the 17th century

At the beginning of the 17th century, the beach was hit by several severe storm surges that eventually led to the island's sinking. Boetius describes a series of floods as particularly bad in 1612, in which the country was under water from September to December, and the great flood of 1615, which hit around 40 wells in the dykes, even damaging the bog dyke through the middle of the island, 300 Killed people, destroyed three churches and flooded almost the entire area between the present-day islands of Pellworm and Nordstrand. It was not until three years later that the dyke breaches were closed again, although the duke had granted generous loans and appointed Johann Clausen Rollwagen, his most capable man, as dikemaster . The churches of Ilgrof and Stintebüll were rebuilt, but the parish of Brunock in between was given up.

Other heavy floods that occurred almost annually between 1617 and 1631, especially the Carnival flood of 1625 , an ice flood , led to more and more damage to the dikes, often before previous damage could be repaired. According to Boetius, disputes over responsibilities also delayed the work, while at the same time reclaiming new land at Pellworm tied up workers elsewhere. The central dykes in particular were neglected. The burden of billeting in the Thirty Years' War and the loss of manpower due to the plague , which raged from 1598 to 1603 and again in 1630, made matters worse . In addition, the repayment of the ducal loan from 1615 tied the residents' financial resources.

Burchardi flood

In the Burchardi flood on the night of October 11th to 12th 1634, the then 220 km² large island broke apart. Within a few hours, a hurricane drew in, which initially blew from the southwest and then turned northwest at spring tide . The water only entered the Rungholter Bay from the south, where a wind build-up formed which the already damaged dikes at Ilgrof and Stintebüll could not withstand. After the wind had turned, the dikes in the north and east of the island also broke. The water broke through the bog dyke from both sides, creating a path across the island. All of the kays were flooded within a few hours. Around 6,400 residents, more than two thirds of the population, drowned, plus an unknown number of foreign dike and harvest workers. 1,339 houses, 28 windmills and six bell towers were driven away, over 50,000 head of cattle perished and the entire harvest was lost.

The Norderhever (Fallstief) formed between the eastern and western parts of the former old northern beach. The fun hole was created north of Pellworm . Since the penetrated water could not run off because of the low location of the land, rather the dike breaches were steadily enlarged by the daily tide , the flooded cultivated land quickly turned into watts . Therefore, land losses were greater on Nordstrand than in the also flooded mainland areas.

consequences

Most of the flooded areas could not be reclaimed. Only on Pellworm did the survivors succeed in re-fortifying the dykes with the help of Dutch dyke builders and regaining four keds by 1637. To do this, however, they had to sell a lot of land to the Dutch. The rest of the country was exposed to the sea for over 20 years. 18 parishes had to be abandoned. Residents who initially on their mounds persevered and vain Wiedereindeichung had tried were compelled to migrate because although Duke Frederick III. In 1635 he banned the rural exodus, he did not provide any support. Services at several churches that had initially stood still were also suspended until 1640. The buildings, which soon became dilapidated due to the daily washing, were demolished and rescued inventory was sold to other churches. So the bell donated by “Hertoch Hans” and Jürgen Boie in 1562 came from Buphever to Osterhever , the Evensbüller pulpit came to Ockholm , the altar from Rörbek to Bordelum .

Already in 1642 Johannes Heimreich, the father of the chronicler Anton Heimreich , and the land clerk Novogk created a new administrative order, according to which the Pellwormharde remained the only administrative unit. The Edomsharde went under with the exception of Odenbüll and parts of Gaikebüll, today Nordstrand . No parish was left of the Beltringharde. Most of the Halligen, which were remnants of the north-eastern coastline, still sticking out of the water after the flood, were also removed in the following decades. Only the Hamburger Koog, won only a few years earlier, remained as Hamburger Hallig .

While some survivors settled on the moor, today's Hallig Nordstrandischmoor , and the Hallig Gröde , Langeneß and Hooge , where churches were now also being built, many left the country, which they could not afford to reclaim on their own, and migrated to Holland or in the Uckermark . According to the report of the Gaikebüller preacher Matthias Lobedantz, only 400, at most 1000 people remained. At the latest the Octroy of Duke Friedrich III., Who recruited dike workers from Brabant to win new imposed kings from the remains of the Edomsharde , displaced the Frisian population from Nordstrand. The island's dialect, Strander Frisian , in which some of the earliest written evidence of the North Frisian language is written, died out.

literature

- Matthias Boetius: De Cataclysmo Norstandico ; 1623

- Boy Hinrichs / Albert Panten / Guntram Riecken: flood disaster 1634. Nature history poetry ; Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster 1991 (2nd edition) ISBN 3-529-06185-9

- Hans Nicolai Andreas Jensen : Attempt at church statistics of the Duchy of Schleswig: Containing the provosts of Tondern, Husum with Bredstedt, and Eiderstedt ; Flensburg 1841; Pp. 643-667

- Dirk Meier / Hans Joachim Kühn / Guus J. Borger: The coastal atlas. The Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea in the past and present ; Boyens (Heide) 2013

Web links

- Enken Johannsen: Development history of Pellworms and the Halligen with special consideration of the large storm surges. Geographical Institute of the University of Kiel , archived from the original on June 7, 2008 .

- Nordstrander story. North Beach Tourism

- Manfred Karl Adam: The Buphever bell in the sound of local history: A small contribution to the great history of Alt-Nordstrand. In: Insel-Museum.de. Archived from the original on November 26, 2011 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Coastal Atlas , p. 75

- ↑ Coastal Atlas , p. 87 f.

- ↑ Johannes Peträus († 1602), quoted in after Albert Panten: Life in North Friesland around 1600 using the example of North Beach ; in: Hinrichs / Panten / Riecken: flood catastrophe 1634 ; Pp. 65-80; P. 70

- ↑ Boetius: De Cataclysmo Norstandico ; P. 15

- ↑ Coastal Atlas , p. 99

- ^ Panten: Life in North Friesland around 1600 using the example of North Beach ; Pp. 67-69

- ↑ Coastal Atlas , pp. 104–110

- ↑ after Boy Hinrichs: The land perishable flood of sin. Experience and representation of your catastrophe ; in: Hinrichs / Panten / Riecken: flood catastrophe 1634 ; Pp. 81-105; P. 85

Coordinates: 54 ° 32 ' N , 8 ° 47' E