Second Marcellus flood

The second Marcellus flood , also: Mandrankels , Grote Madetuen or Grote Mandrenke ("great drowning"), describes a devastating storm surge that affected the German North Sea coast from East Friesland to North Friesland . According to later tradition, it began on January 15, 1362, reached its peak on January 16 - the day of Marcelli Pontificis , i.e. the day of the canonized Pope Marcellus I , after which it was named Marcellus Flood - and only fell off on January 17th . In this flood, the North Frisian Uthlande are said to have been torn apart. Around 100,000 hectares of the best cultivated land were lost. Around 200,000 people died between the Elbe and Ripen . Rungholt , the largest trading center in the north at the time, was lost.

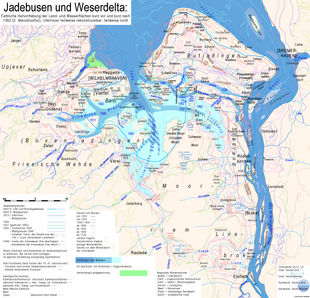

The creation of Dollart , Leybucht and Jadebusen was also associated with this date. Contemporary sources in England, Holland and Bremen only report a storm from the west, southwest and south that will have spared the southern North Sea coast. In the German coastal research of the 20th century, however, the storm surge has played a key role since Carl Woebcken , where it was made responsible for a large part of the land loss in the late Middle Ages. The Dutch coastal researcher Elisabeth Gottschalk was, at least for the Netherlands, "extremely skeptical [because she] could not find a single authoritative contemporary source" that provided evidence of the massive impact of this storm surge.

Sources and dating

At first there were only oral records about the second Marcellus flood. Although no other flood has "engraved itself so deeply in people's memories", the chronical records, which date back to the 15th century at the earliest, are "to be enjoyed with caution". In his work De Cataclysmo Norstandico (1615), for example, Matthias Boetius dated the sinking of Rungholt in 1300 and the Marcellus flood itself to 1354 according to local reports. The Husum town preacher Peter Bokelmann spoke in a festive sermon from 1564 about the Man-Drenkelß of 1354. Other chroniclers such as Neocorus and Peter Sax put the Marcellus flood at 1300. The rupture of the North Frisian Uthlande was dated to 1338 by Peter Sax and the Nordstrander chronicler Johannes Petreus . The latter was very critical of his sources. The folklorist Bernd Rieken therefore considered it possible that the day was passed down correctly because such a devastating storm surge fell on Marcellus Day a second time after 1219 , but the exact year was not preserved in the oral tradition. However, dating to the Marcellus day only became established quite late. Other chronicles reported from Latare (1362 March 27th) or the Birth of Mary (September 8th). The Dutch climate researcher Jan Buisman, who has evaluated almost all contemporary chronicles of Northwest Europe, therefore warned against hasty conclusions:

“It cannot be ruled out that accidents have occurred on the north German coast, especially in the area of the Jade Estuary, as has been claimed for centuries, but there is no irreproachable evidence for this. Perhaps there was a local dike breach on the Lower Weser. It is possible that floods have occurred further north, on the islands or on the coast of North Friesland, where the storm may have been stronger from the west or north-west. But even in these areas we will get no further than speculation without further studies. [...] It is time to put an end to the uncertainties and assumptions that have prevailed for decades. "

More recently, the comparison of data has shown correlations with storm surge events such as B. be produced on the British coast: Large parts of the port city of Dunwich were therefore probably destroyed a day before Rungholt.

The preconditions

Levees

In the 11th or 12th century the inhabitants of the marshes began to protect themselves from the tides with dikes . Most of them only stayed low dikes to protect the fields during the growing phase, each dyke construction, however, has the consequence that the diked areas by natural or artificial drainage through sluices to sag, which no longer sedimentation is compensated at regular flooding. At the same time, the tidal range usually increases in dammed creeks .

Land use

The mining of salt peat to obtain fuel and salt caused the land to sink further, often below sea level , so that after a dike breached the water could no longer drain away. Plowed soil offers the water a larger area to attack than continuous vegetation. Floods lead to erosion . In addition, arable farming requires drainage , which in turn promotes subsidence of the soil. The island of Nordstrand largely consisted of reclaimed high moor that gradually sank and was consumed. Up until the early modern times there were locally raised bog layers three to five meters high. These were often lifted up by the floods and - if they did not collapse - moved to other places.

Previous storm surges

Although the water level in the North Sea probably fell by a few decimeters between 1000 and 1400 , the North Sea coast was hit by many severe storm surges in the 13th and 14th centuries , often with large land losses. B. in the years 1287 and 1347. The following floods in particular caused severe damage, even at lower altitudes, when they hit dykes that were deepened (as a result of the strong currents caused by the storm surges).

The 14th Century Crisis

A climate change , the beginning of the so-called Little Ice Age , had caused poor harvests in the coastal areas in the decades before the flood, so that the inhabitants were less wealthy than at the beginning of the 14th century. The " Black Death ", the great European pandemic (mostly known as the plague epidemic), which also spread along the North Sea coasts, decimated the population even more. In 1349/1350 there had been a devastating plague epidemic. The weakened population was no longer able to maintain the dykes. Only twenty years before the Marcellus flood, the Magdalen flood in 1342 , a devastating heavy rain event, devastated large parts of Central Europe.

The flood in North Frisia

The floods partially pierced the marshes as far as the Geestrand . The old coastline with its protective spits was completely destroyed, the tidal creeks , previously only shallow, dry lows between the marsh islands lying close together, deepened into tidal currents that let the water penetrate deeper into the land with each subsequent tide. The first Halligen emerged in North Friesland . How much land was lost up to the middle of the 15th century cannot be exactly reconstructed, since no exact maps exist from this time. The names of the lost churches and places in North Friesland can be deduced from the Waldemar earth book and church registers from 1305 and 1462. About 24 churches were on the north beach and the Halligen (as far as they already existed), the rest on the mainland. However , the land probably did not reach as far to the west as the reconstruction by Johannes Mejer around 1650 shows.

The oldest source about the storm surge in 1362 comes from a copy of the lost Schleswig city book, where the entry can be found:

In 1666, three centuries after the flood, the chronicler Anton Heimreich described from older sources that the stormy West Sea had passed four cubits (about 2.4 meters) over the highest dykes in North Friesland . The flood caused 21 dike breaches, the town of Rungholt and seven other parishes sank in the Edomsharde and 7600 people perished. This last number can be found at Neocorus . For the entire west coast from the Elbe to Ribe, the chronicles speak of 100,000 dead, a number that is certainly very much exaggerated.

Johannes Petreus read in the chronicles that God had punished the inhabitants because they did not want to recognize him. Many people and cattle died and the dikes could not have been restored because of a lack of people and bread grain. Since the residents were unable to rebuild the dykes in the years after the flood, more land was lost in the floods of the following decades, so that - according to a report by Bishop Nikolaus Brun - a total of 44 churches and parishes in North Friesland were affected were. The Norderhever was created as a large tidal creek in the mudflats, which after the Burchardi flood of 1634 tore the remains of Strand in two.

East Frisia and Oldenburg

In East Friesland , the Leybucht and Harlebucht were enlarged by different floods since the second half of the 14th century . At the Jade Bay , the formed Black Brack between Ellens , sand and Neustadtgödens , Butjadingen and Stadland became islands. At the beginning of the 15th century the Emsdeich broke near Emden on the opposite side , which led to the first dollar slump and the downfall of the village of Janssum. The church village Otzum and other villages near Harle Bay were lost. The island of Juist was probably separated from Borkum around this time .

The Marcellus Flood was probably hardly to blame for this. Only the Norder Annalen report that on Marcellus Day 1361 many solid houses and church towers , including the tower of the Dominican monastery from the north , were blown over by the wind. Many large trees were uprooted and the dikes on the Westermarsch were leveled by water, drowning many people and cattle in their homes. This corresponds to the effect of a storm from the southwest. All that is reported from Butjadingen is that two rectories and thirty farms in the Banter parish were blown over. Almost all the villages that perished here in the 15th century were still there around 1420.

On the Stollhammer dike in the Wesermarsch district, near the northeast corner of the Jadebusen , the remains of a village urt from the 11th or 12th century were discovered, which - as is believed - fell victim to the second Marcellus flood. The finds, which were made under a 1.3 meter thick layer of clay, consist of broken bricks and basalt (millstone), wood, ceramics, leather, metal and bone objects, cinder and cloth.

The consequences

Large areas of cultivated land were lost in the flood.

After this flood, the first land reclamation measures began in North Frisia, that is, people tried to wrest the lost land from the sea by organizing dykes. Up to this point, only low summer dykes had been built, which only protected the built-up land from the mostly lower storm surges in summer. The life of man and cattle was protected from the violence of the sea primarily by the construction of terps . After the devastating flood, new sediments were deposited on the higher and more protected areas of the submerged land, creating new layers of fertile marshland. This "growth" was gradually diked and won to new kings .

The effect of the flood was remembered as so devastating that the Burchardi flood , which destroyed large parts of the remaining island of Alt-Nordstrand , was also referred to as the Second Grote Mandränke . The story of Rungholt has often been exaggerated mythically, best known probably through Detlev von Liliencron's poem Trutz, Blanke Hans . Only when the remains of the historic Rungholt were found in 1938 did historical science recognize the real former existence of the place.

See also

literature

- Marcus Petersen, Hans Rohde: Storm surge. The great floods on the coasts of Schleswig-Holstein and in the Elbe , Neumünster 1977

- Lower Saxony State Office for Monument Preservation : Archeology in Germany. 4/99, pages 39-40

Web links

- Fateful floods: The Grote Mandränke as an NDR report from January 16, 2012

Individual evidence

- ^ "North Friesland - then and now", Ingenieurbüro Strunk-Husum, printed by Bogdan Gisevius, Berlin West (with maps of North Friesland around 1240, 1634 and today, which the Husum cartographer Johannes Mejer created in 1649).

- ↑ Jan Buisman: Duizend jaar weer, wind en water in de Lage Landen , Dl. 2: 1300-1450, Franeker 1996, pp. 207-213. Reimer Hansen: Contributions to the history and geography of North Frisia in the Middle Ages. In: Journal of the Society for Schleswig-Holstein History 24 (1894), pp. 1–92, esp. Pp. 12–16, 31–44

- ^ Carl Woebcken: Dykes and storm surges on the German North Sea coast , Bremen / Wilhelmshaven 1924, Neudr. Leer 1973, pp. 75–76. The emergence of the Dollart , Aurich 1928, pp. 35–36

- ^ MK Elisabeth Gottschalk: Stormvloeden en rivieroverstromingen in Nederland . Vol. 1, 1977, p. 375

- ↑ Bernd Rieken: North Sea is Mordsee: Storm surges and their significance for the history of mentality of the Frisians , Nordfriisk Instituut Volume 187. Münster 2005; Pp. 169-170

- ^ Rieken: North Sea is Mordsee , p. 207

- ↑ Buisman: Duizend jaar weer, wind en water , Vol. 2, pp. 210, 213.

- ↑ - ( Memento from February 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ "Rungholt. Mystery of the Atlantis of the North Sea ”. The causes of the flood , scinexx, April 25, 2008

- ↑ See the representations in Jürgen Newig: The coastal shape of North Friesland in the Middle Ages according to historical sources ( PDF , 1.23 MB, accessed on May 20, 2012)

- ^ Albert Panten: The North Frisians in the Middle Ages . In: Nordfriisk Instituut (Hrsg.): History of North Friesland . Heide Boyens & Co 1995. ISBN 3-8042-0759-6 , p. 72

- ↑ "Grote Mandränke" brings death and misery ( page no longer available , search in web archives ). Article in the Nordwest-Zeitung from January 16, 2012.