Eye for eye

Eye for eye ( Hebrew עין תּחת עין ajin tachat ajin ) is part of a legal sentence from the Sefer ha-Berit (Hebrew covenant book ) in the Torah for the people of Israel ( Ex 21,23-25 EU ):

"[...] you should give life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, brand for burn, wound for wound, welt for welt."

According to the rabbinical and predominantly historical-critical view, the law requires appropriate compensation from the perpetrator for all crimes of bodily harm , in order to make the blood revenge that was widespread in the ancient Orient illegal, to replace it with a proportionality of offense and punishment and equality before the law for men and women, the poor and create empires.

In the history of Christianity, the legal sentence was often translated as "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth ..." and interpreted as a Talion formula (from Latin talio , " retribution "), which calls on the victim or his representative to "pay back" or "repay" the perpetrator with like with like . to atone for his offense ("as you me, so I you"). However, the biblical context and Jewish tradition contradict this interpretation.

Both views have influenced the history of religion and law.

Precursors and analogies in antiquity

The legal principle comes from an older ancient oriental legal tradition. The Codex Ešnunna (around 1920 BC), one of the earliest known legal texts from Mesopotamia , regulated bodily harm with precisely graduated fines:

“When a man bites off a man's nose and cuts it off, he pays a mine of silver. He pays one refill for one eye, half a refill for a tooth, half a refill for an ear, ten shekels of silver for a blow on the cheek [...]. "

The Babylonian King Hammurabi (1792–1750 BC) collected offenses and the corresponding judgments as case studies ( casuistry ). His Codex Hammurapi , discovered in 1902, summarized them in 282 paragraphs and made them publicly accessible on a stele . There is also a number of precise penalties for bodily harm:

“Assuming that a man has destroyed the eye of a freeborn, then one will destroy his eye ...

Assuming that a man has knocked out a tooth from another man who is equal to him, then one will knock out his tooth ...

Suppose he has destroyed an eye of a slave or broken the bone of a servant, he pays a mine of silver. "

Hammurapi can thus have introduced the Talion principle (Latin ius / lex talionis ) for these cases or made existing customary law legally binding. The Babylonian class law applied different standards to slaves than to property owners: Those who injured dependents could buy themselves out, but whoever injured a free full citizen should suffer corporal punishment of the same kind . This should fix, centralize and tighten older, orally handed down law. It is controversial whether this innovation came from nomadic clan law and reflected actual jurisprudence.

Other law reformers of antiquity tried since the 7th century BC. To limit violence and arbitrariness and to standardize criminal law: This is how Drakon made a distinction in Athens in 621 BC. Like the Torah, intentional and unintentional killing and referred the examination to special courts of law. Demosthenes (384–322 BC) narrates a about 650 BC. Law issued by Zaleukos from the southern Italian colony of Lokroi :

"If someone knocks out an eye, he should suffer that his own eye is knocked out, and there should be no possibility of material compensation."

Zaleukos was considered the first Greek to set laws in writing. He apparently wanted to counteract perversion of the law, corruption and social contradictions by setting the sentence and excluding ransom.

In Roman law , on the other hand , a perpetrator could prevent punishment on indictment of the victims' relatives ( Actio arbitraria ) by making amends for the damage, for example through in rem restitution . Thus the Twelve Tables Law required around 450 BC Chr. In panel VIII, sentence 2:

"If someone breaks a limb, the same thing will happen [Latin talio esto ] if he does not come to an agreement [with the victim]."

Hebrew Bible (Tanakh)

After a long oral tradition, the formula “eye for eye” found its way into the Torah at the latest when it was around 700 BC. Their writing began. Around 250 BC This part of the Hebrew Bible ( Tanach ) was finally canonized. The formula appears once in each of its three most important sets of commandments: the covenant ( Exodus 22–24), the holiness law ( 3rd book Moses 17-26) and the Deuteronomic law ( Deuteronomy 12-26).

Federal Book

“ 22 When men argue with each other and hit a pregnant woman and cause her to miscarry without causing further harm, the perpetrator should pay a fine imposed by the woman's husband; he can make the payment according to the judgment of arbitrators. 23 If further damage has occurred, then you must give: life for life, 24 eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, 25 stigma for stigma, wound after wound, welt for welt. 26 If someone knocks out one of his slave's eyes, let him go free for the knocked out eye. 27 If he knocks a tooth out of his slave, he should release it for the knocked out tooth. "

The formula is in the context of bodily harm resulting in death (v. 22): A woman loses her unborn child as a result of a fight between men, but does not suffer any permanent injury herself. The loss should be compensated with an appropriate fine: tachat (Hebrew תחת) means in the Bible instead of, instead of, representative (e.g. in Gen 4,25 EU and 1 Kings 20,39 EU ).

The aggrieved husband may determine the amount of the compensation, but a judge should mediate the payment. An orderly legal process is required. Whether the damage was caused intentionally, negligently or inadvertently is not expressly stated and is apparently not relevant here, since the uninvolved injured party is always entitled to compensation.

A permanent physical impairment, including the death of bystanders, should also be adequately compensated (v. 23): "... so you should give ..." This legal principle addresses the person who caused the damage, not the person who has suffered damage. He confirms to him the lawful claim of the injured party for compensation appropriate to the damage. The enumeration of each individual wound (v. 24f) aims to indicate a measurement of the compensation: what is required is a sense of proportion and an exact correspondence between punishment and damage.

The following example (v. 26 f.) Confirms that it is not the injured party who is asked to mutilate the perpetrator. Rather, the polluter should repay the consequences of the damage by releasing the permanently injured slave who could only perform his service to a limited extent. Also Ex 21.18 f. EU talks about compensation for bodily harm:

"If men get into an argument and one hits the other with a stone or a pick, so that he does not die but becomes bedridden, can get up again and go out with his stick, then the one who hit him should not be punished, but pay him what he has missed and give the medical fee. "

How bodily harm resulting in death can be replaced remains open here. These different Ex 21.28 to 32 EU an accident of negligent homicide : A man who knew his stößiges cattle people at risk to die if the ox someone comes to death (v 29). If he could have avoided the accident, the perpetrator would have to stick with his life; only in the event of the death of a slave can he compensate his owner with money (v. 32).

Holiness law

“ 17 Whoever kills a person deserves death. 18 Whoever kills a head of cattle must replace it: life for life. 19 If someone injures a fellow citizen, do what he did to him: 20 break for break, eye for eye, tooth for tooth. The harm that he has done to a person should be done to him. "

Here, too, the Talion formula is related to compensation: one should replace a dead animal with a living head, i.e. give life, not take it. In the case of bodily harm, however, the perpetrator should suffer damage that corresponds to his act. The active translation suggests corporal punishment; but there is a passive in the original text:

"And if someone injures his neighbor - just as he did, let it happen to him."

As a passive divine (not naming God, but meaning passive), it demands that the execution of the commandment be left to God's disposition (connection between doing and doing ).

Human life is definitely irreplaceable. Murder and manslaughter cannot therefore be compensated for with a fine. For this, the Torah provides for the death penalty , which is also formulated in the passive divinum :

“Whoever kills a head of cattle must replace it; but whoever kills a person will be killed. "

Verse 22 expressly applies this command to everyone, including strangers. The pricelessness of human life is justified in the Noachidic commandments with the permanent likeness of every human being:

“Whoever sheds blood of a person, for that person's sake his blood will also be shed. Because he made man as the image of God. "

Deuteronomy

" 16 If a wicked witness appears against someone to accuse him of a wrongdoing, 17 both men should appear before YHWH in this dispute , before the priests and judges at that time, 18 and the judges should investigate thoroughly. And if the false witness has given a false testimony against his brother, 19 you should do to him as he intended to do to his brother, so that you can remove evil from your midst, 20 so that others will listen, be afraid and no longer do such evil things in your midst. 21 Your eye should not spare him: life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot. "

A false charge and perjury should therefore be treated according to the principle of talion: What the plaintiff wanted to inflict on the accused should be demanded of him. Addressed here is the court, which is supposed to uphold the law and deter witnesses from willful defamation . The context is legal protection for murderers wrongly persecuted as murderers by places of asylum ( Dtn 19.4–7 EU ) and the rule that death sentences are only legally valid for at least two independent eyewitnesses of the crime ( Dtn 19.15 EU ). It is all the more difficult for the Torah to attempt to destroy this protection with false accusations.

The Tanakh does not hand down any corporal punishment that was justified by the Talion command, and no court judgments that allowed such punishments. Chastisement is generally limited to a maximum of 40 strokes in the case of judicially established guilt in order to protect the honor of the convicted ( Dtn 25.1–3 EU ). This ruled out a literal application of the Talion Law. The commandment to love one's neighbor expressly excludes hatred and revenge as a motive for punishment and instead requires reconciliation with the opponent ( Lev 19,17f EU ). Accordingly, Spr 24.29 EU demands to forego retaliation:

"Do not say: 'As someone does to me, so I will do to him too and reward everyone for what he does.'"

The preceding verse equates this resolution of retaliation with lying and deceiving one's neighbor.

Jewish interpretations

The Talion formula was discussed intensively in Judaism even before the turn of the century. In the 1st century, the Pharisees established a legal practice that stipulated precisely graduated fines (Hebrew tashlumim: "serving peace") for all cases of bodily harm, including those resulting in death - except murder . The main idea was the restoration of the legal peace between the injured and the injured, conflict management and prevention of further consequences of violence.

According to the Antiquitates Judaicae of Flavius Josephus , physical retribution in Judaism was only carried out if the injured party was not satisfied with a fine on the perpetrator. This corresponded to Roman legal tradition. Then financial compensation would have been the rule back then, corporal punishment the exception. Therefore, the British Judaist Bernhard S. Jackson assumed that the damages had replaced corporal punishment before the end of the Tanach (around 100).

According to the Chronicle Megillat Ta'anit , the Sadducees and Rabbi Elieser (around 90) took the Talion formula at least theoretically partially literally. Rabbi Hillel , on the other hand, taught that reparation must restore the original state (restitution); his attitude continued in the first century against the stricter school of Shammai through. The Mishnah (around 200) therefore does not deal with corporal punishment in the Bawa Qama (BQ 8.1) treatise , but names five areas in which compensation is to be paid: compensation (neseq), compensation for pain and suffering (zaar), treatment costs (rifui), compensation for lost work ( schewet) and shame money (boschet).

In the comments of various rabbis on this (BQ 83b – 84a) the literal application of the Talion Law is discussed but expressly rejected. In conclusion, the tract follows the opinion of Rabbi Hyya:

"'Hand for hand' means something that is passed from one hand to the other, namely a cash payment."

Nonetheless, it remained controversial whether “life for life” in Ex 21.23 as well as in Lev 24.17 demands the death penalty, because human life is irreplaceable. The treatise Ketubboth (35a) in the Babylonian Talmud discusses the fundamental difference between the penalties for killing an animal and a person. While the former always imposes a fine, the latter always overrides this obligation.

Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808–1888), one of the leading rabbis of neo-orthodox Judaism in the German Empire, understood Ex 21.23 in contrast to v. 22 ("but there is no death") as an accident resulting in death:

"But if there is a death, you have life for life to give."

Then no compensation is possible; Life is irreplaceable in any case. The German rabbi and biblical scholar Benno Jacob (1862–1945), on the other hand, argued that wherever the term tachat appears, there is an obligation to pay compensation. He translated the same verse:

"But if an accident happens, you should give life substitute for life."

He also took into account that a human life for the Torah is the highest of all goods worthy of protection and never outweighed with money. But he interpreted the pregnant woman's child loss as an example of a tragic accident ( Asson v. 22), not as negligent homicide, manslaughter or murder. Therefore the right of the injured party to a monetary payment comes into play here as well. They would not have to take advantage of this, but the judges would definitely have to award compensation to the man of the injured party: “This is how you should give”, referring to the judge in the previous verse.

The writing (1926–1938) by the Jewish theologians Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig translated the Talion Law as follows: "If the worst happens, give life substitutes, eye replacements for eyes, dentures for tooth ..."

Historical-critical interpretations

The Old Testament science classifies the Talion formula on the one hand in the inner-Israelite, on the other hand in the ancient oriental legal and social history. The main questions are their origin, the period of their inclusion in the Torah, the relationship between legal norms and practical application and their theological significance. As in Judaism, the individual exegesis revolves on the one hand around the presupposed case study in Ex 21:22: What do the two arguing men have to do with the pregnant woman; the injured husband is one of them; is the death of the unborn child to be understood as an accident or negligent homicide? On the other hand, the tension of the Talion formula v. 23f is explained differently: Who is addressed here with "you", how does the personal address relate to the anonymous if-then formulation in the frame verse, which case is meant by "permanent damage" ?

Usually the isolated formula is understood as limiting the blood revenge: This archaic clan law allowed the relatives of a dead or injured person to retaliate. Where a member of the group was harmed, this required harm to the group of perpetrators in order to balance the balance of power between the two. This could degenerate into a generation-long spiral of violence and mutual attempts at extermination, as suggested by Gen 4,23f EU :

“And Lamech said to his wives: […] I killed a man for my wound and a boy for my lump. Cain is to be avenged seven times, but Lamech seventy-seven times. "

It is widely assumed that the Talion formula was intended to curb this widespread imbalance between offense and punishment: Instead of arbitrarily and unlimited revenge for injustice suffered, the injured party or his relatives were only allowed one life for one life, one eye for one, in court Eye to ask for a tooth for a tooth. In order to avoid the escalating blood revenge and to protect the survival of the clan, it was important that the perpetrator could be demanded for each degree of damage in return.

The origin of the formula is controversial, as both the older Babylonian and the more recent Greco-Roman legal texts use it differently from the Bible. Albrecht Alt assumed in 1934 that “life for life” originally referred to the replacement of human sacrifice by animal sacrifice. Hans Jochen Boecker contradicted this in 1976: The formula has nothing to do with the Israelite cult of sacrifice and the relationship to God, but comes from nomadic family law that was widespread throughout the ancient Orient. It is not a general principle of retribution in the Torah, but refers exclusively to specific cases of bodily harm and damage to property. Compensation for this was not negotiated between victims and perpetrators, but in public court proceedings. Boecker understood “life for life” as the heading for the following facts, which followed the anatomy of the body from top to bottom: eye - tooth - hand - foot. Only the last items in the list, branding - wound - welt, are without an ancient oriental model. The Bible authors would have added it to apply the formula to minor bodily harm.

In 1987, Frank Crüsemann denied the acceptance of general oriental legal progress from blood revenge over corporal punishment to damages in kind and / or fines. Conversely, he understood the Talion formula extended in Ex 21:24 as a late insertion into an older law on damages. In the event of bodily harm resulting in death, compensation is excluded: This aims to provide legal protection for the weak, which Chapter 21 is about. In contrast to the examples in its context, the Talion formula makes no distinction between slaves and free people; in the Bible it applies to all people. It prevents the slave owner from buying himself out, and instead demands the release of a slave who has been injured by him, and in the event of his death even the liability of the perpetrator with his life.

Some Old Testament scholars such as Hans-Winfried Jüngling and Ludger Schwienhorst-Schönberger agreed with the rabbinical tradition of interpretation, according to which the formula in the Tanach itself was based exclusively on compensation for bodily harm. They understood the ranking of the formula as in the Codex Eschnunna as a "tariff table" which only required the financial graduation of the sanction appropriate to the damage "(you should give ...)."

Eckart Otto, on the other hand, understood the 1991 formula again as a requirement for real corporal punishment, which should replace the blood feud. But it has been around since 1000 BC. Chr. For their part gradually replaced by a conflict settlement and at the time of their inclusion in the Pentateuch was no longer practiced. It is only cited as a relic of what the perpetrator actually deserves. However, this was revoked by the specific examples of replacement services in their context.

New Testament

In the so-called antitheses of the Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5: 1–7, 28f.) - originally scattered, situational, oral interpretations of the Ten Commandments and other important Torah commandments - Jesus of Nazareth also refers to the Talion formula ( Mt 5: 38f EU ):

“You have heard that it was said, an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.

But I tell you: Don't resist anyone who does you harm,

but if someone hits you on the right cheek, then hold the other out to him too. "

The Hebrew tachat is translated here according to the Septuagint with the Greek anti , which has a similar range of meanings. However, here Jesus is not addressing the perpetrator about his obligation to pay damages, but the victims of violence. He relates the formula not only to individual bodily harm, but to the situation of the entire Jewish people at that time, affected by violence and exploitation (Mt 5: 1–11). He characterizes this as "evil", which should not be resisted with counterviolence , but rather countered with love for one's enemies (Mt 5,44ff).

At that time, the poor with no rights could not assert their claims in court because Israel was under Roman occupation law. In the prophetic tradition, hardship and foreign rule were always understood as the result of collective disregard for the will of God. Accordingly, Jesus removes the legal principle of "eye for eye" from the damage settlement and relates it to Israel's total damage, the rule of evil: Since the kingdom of God is at hand, Jews should forego claims for compensation and meet hostile violent criminals with benefits in order to "disarm" them. and to become “God's children” with them. In it they should depict God's perfection.

Like other Torah sermons of Jesus, this one does not question the validity of the commandment, but tries to preserve his original sense of direction in a concrete situation: unlimited counter-violence that the Talion formula wants to ward off can now only be avoided by renouncing compensation. The obvious but deadly reaction pattern, which demands reparation according to one's own standards and enforces it arbitrarily, is to be replaced by behavior geared towards conflict resolution and legal peace with the opposing party.

This was in keeping with biblical tradition. Prov 15.18 EU praises the virtue of the believer to avoid a legal dispute through an amicable settlement and to achieve reconciliation in advance ( Prov 17:14 EU ), as the commandment of charity ( Lev 19.17ff EU ) not only applies to Jews, but also non-Jews ( Lev 19.34 EU ) required. Jesus reminded of this in Mt 5:24 EU . In the lamentations of Jeremiah ( Klgl 3,30 EU ) it is also demanded: "He offer the cheek to those who strike him, he will be satisfied with the shame." In Isa 50,6 EU the prophet says that he fulfills this commandment and did not resist the disgrace of slaps in the face, but held out his cheek.

In Romans, Paul of Tarsus confirms the correspondence between Jesus' teaching and the Torah by alluding to his commandment to love one's enemy and justifying it with the biblical prohibition of vengeance ( Deut. 32.35 EU ) ( Rom. 12.17-21 EU ):

"Do not retaliate evil with evil [...] but overcome evil with good."

Christian interpretations

The Sermon on the Mount emphasizes the contrast between the renunciation of rights and retribution, love of enemies and hatred of enemies (Mt 5:43). Such a command to contrast is unknown in the Tanakh and in Judaism of that time; the evangelist contrasts the Jesuan commandment with the zealot interpretations of the commandment of retribution in the case of murder (Gen. 9.6). On this basis, Christian interpreters often understood the biblical commandment of the Talion as a central point of difference between Jesus and the Pharisees, the New and Old Testaments, Christianity and Judaism.

Martin Luther translated the sentence as “an eye for an eye”, where “around” could also mean replacement. However, he related the legal sentence to the judging, punishing “law” of God and compared it with the “ gospel ” of God's unconditional grace . In the public sector, the God decreed authorities should exercise strict retaliation on criminals and rebels, only in the ecclesiastical and private sector there is room for forgiveness , grace and love of enemies (see doctrine of the two kingdoms ). This separation encouraged the misunderstanding that the Talion law was a logic of retribution, which Jesus wanted to replace with a logic of forgiveness that was only valid for the believers and in the kingdom of God beyond.

John Calvin commented on Mt 5.43 LUT, contrary to the facts known from the Talmud, in his Institutio Christianae Religionis IV / 20.20: "This is how the Pharisees instructed their disciples to seek vengeance." But he emphasized more than Luther the role of the Talion law in limiting violence as a basic principle of all public law:

“A fair proportion must be observed, and ... the extent of the punishment must be regulated immediately, whether it is a tooth or an eye or life itself, so that the compensation corresponds to the injury done ... as if his Knocked out his brother's eye, or cut off his hand, or broke his leg in order to lose his own eye or hand or leg. In short, as a goal of preventing all violence, compensation in proportion to the injury must be paid. A fair proportion instead of escalating acts of violence: That is the law, and the germ of this thought has always been at the center of law. "

In 19th-century Christian theology, the Talion Law was mostly seen as an expression of a primitive spirit of vengeance and god of vengeance, limited to Israel's national self-assertion, to whom Jesus contrasted the image of the loving God and a completely new ethic of general human love . This stylized it as the epitome of the difference between Judaism and Christianity:

“Other laws, on the other hand, are branded as 'cruel Old Testament' or even as 'Jewish'. For example the famous Talion Law (§ 124): an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. The New Testament Gospel was and is opposed to this law, and indeed is opposed to it. With the spirit of the gospel, Christians would have overcome the rigid Jewish law. Law is equated with death, the gospel with life. The whole construction goes hand in hand with a latent, especially in our century but also virulent anti-Judaism , which is still having an impact today. "

Today's exegetes like Thomas Schirrmacher emphasize that Jesus did not want to revoke the right of the injured party. At the time of Jesus, the Talion requirement was generally fulfilled by a fine limited to the damage. For a long time, this civil law had only to be enforced in state courts, as stated in the Torah. The authorities therefore remain in the NT despite the commandment of love according to Rom. 13.4 "God's servant, an avenger for punishment for those who do evil". Jesus does not override this duty of the state to provide legal protection in Mt 5: 38-48, but rather presupposes it, since Mt 5:40 mentions a court, Mt 5:25 "judge", "bailiff", "prison".

That is why Schirrmacher understands Mt. 5,39 "Do not resist evil ..." not as a principle prohibition of self-defense and legal entitlement, but as a situation-related waiver: from the insight that the insistence on one's own right given in the concrete Persecution of the addressed can exacerbate the violence and increase the damage. It presupposes a clear distinction between good and bad, so it does not make right and wrong indifferent. Evil (personal or neuter) means violence, hitting, insulting and disenfranchising, which Mt 5: 39-41 illustrates:

“The statement of Jesus would then be that a Christian does not get himself right by means of the principle of judgment, the 'lex talionis', but lets himself suffer injustice. For the sake of peace, a Christian is not only able to forego a court hearing, but also to allow what is wrongly demanded by him to an even greater extent than demanded. "

The attempt at arbitration, mediation, even reconciliation, is biblical and for Christians should always come before proceeding with legal means, as these do not always lead to the desired clarification. The personal willingness to lose out should always be present. This is not an alternative, but a necessary addition to the lawful procedure.

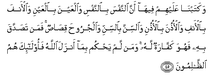

Koran

The Koran quotes the biblical Talion formula in Sura 5:45 . This is addressed to the people of the book (Jews and Christians) to remind them of the true revelation of God which they have falsified:

“And we have prescribed for them: life for life, eye for eye, nose for nose, ear for ear, tooth for tooth;

and retribution also applies to the wounds.

But whoever gives this as alms, it is an atonement.

Those who do not judge by what God has revealed are the ones who do wrong. "

The quote emphasizes the fundamental right to retaliate in the event of serious and minor bodily harm, which is mentioned separately. Victim members can, however, forego the retribution due to them and thus obtain atonement for their own sins. It is unclear whether this "alms" means compensation for the perpetrator. Whoever forbids retribution or exceeds the stipulated equality, but also whoever excludes the possibility of forgiveness, breaks a law revealed by God for the Koran and thus becomes a criminal himself.

Sura 2 , 178f makes the commandment of retribution binding for all Muslims:

“Oh you who believe! Retaliation is prescribed for you in the event of manslaughter: one suitor for one free, one slave for one slave and one woman for one woman. "

The following verse allows the victim relative entitled to kill the perpetrator to request compensation instead:

“If something is slacked off by your brother, then the collection [of the blood money ] should be done in the right way and the payment to him should be done in a good way. Let this be a relief from your Lord and a mercy. "

In general, however, the following applies:

"In retaliation, life lies for you, oh you discerning ones, so that you may become God-fearing."

This emphasizes the importance of this commandment for the life and faith of all Muslims. Retribution thus takes on theological status: It corresponds to the obedience-rewarding, injustice punishing justice of God.

Sura 17 , 33 relates this to the breach of the prohibition of killing:

“Do not kill the person whom God has declared inviolable, unless authorized to do so.

If someone is killed unjustly, we give authority to his closest relative (to avenge him).

Only he should not be excessive in killing; he will find support. "

This gives the relatives of a murder victim the right to retaliate. It remains open whether the promised assistance relates to God or a judge.

The Qur'an thus sets clearly different accents than the Torah: It also relates “one life for one life” to murder, whereby it does not emphasize the equality of punishment and harm, but the equality of victim and perpetrator. From this he derives the victims' direct right to atonement. This passage does not mention renouncement, possible forgiveness and the atonement allowed as replacement according to sura 2,179. Instead of listing and compensating each individual damage, there is a warning to be moderate.

Islamic legal tradition

The Sharia regulates the application of the Koran suras to the Talion law for all offenses against the life and limb of other people ( Qisās ) . The right of the victims' relatives to retaliate is linked to conditions:

- An Islamic court must determine the culprit's guilt. The testimony of the victim and another witness, but also circumstantial evidence, are sufficient for the conviction.

- If there is a judgment, the victim or his family may inflict exactly the same harm on the perpetrator under the supervision of the judge that he inflicted on the victim.

- In homicides, there is only trial if the victim's next male relative requests it in court.

- The perpetrator and victim must also be “the same”: only one other man may be killed for a man, another woman for a woman, and a slave for a slave. The execution of Muslims for the death of non-Muslims ( dhimmis and harbīs ) is excluded because the Talion only applies between Muslims who are regarded as "equal".

- If inequality between perpetrator and victim excludes a death sentence, the victims' relatives can claim a blood price (diya) . A judge determines this according to the severity of the offense.

- The punishment for the offender is then at his discretion and can range from acquittal to the death penalty.

- In addition, the perpetrator must definitely do a good deed for God, such as fasting or making a donation, or release a slave earlier.

- Proceedings are stopped immediately if the victim or his relatives forgive the perpetrator or if the perpetrator shows credible and lasting remorse.

In Islamic states, the Sharia can be interpreted very differently because of different schools of law; the jurisprudence depends on the consensus of opinion and action of the theologians ( ijma ). However, corporal punishments such as hand amputation for theft etc. a. Common in Saudi Arabia , Iran and Yemen to this day. Sections 121, 297, 300, 881 of the Iranian Civil Code and Section 163 of the Constitution differentiate the law for Muslims and non-Muslims in murder cases.

European legal tradition

While the Jewish legal tradition has hardly gained any influence in Europe since the turn of Constantine and was only cultivated autonomously in isolated Jewish communities, Romanization influenced all of Europe for centuries. In the Middle Ages, Roman legal systems merged with legal conceptions from Germanic tribal law . In the north, feuding practices were increasingly being replaced by catalogs of penalties that the authorities established. These, however, represented situational individual regulations rather than general codifications .

Up until the High Middle Ages , criminal law in the case of bodily harm was mainly based on private penalties: an injured person or his relatives could demand a statutory atonement from the perpetrator. In the 13th century, however, two related tendencies opposed this:

- Criminal and civil law were separated: the private penal law was more and more replaced by the official "embarrassing punishment" for life and limb.

- This blood jurisdiction became a matter for the respective sovereigns and lost its uniformity.

The Sachsenspiegel of 1221 still allowed the replacement of bodily mutilation by penance, although it already made the former the rule. In the period that followed, corporal punishments and death sentences increased. They were also justified by the biblical commandment to talion. The reasons for this lay in small states and feudalism : the sovereigns reacted to economic misery, monetary devaluation and the increase in the number of robbers with ever more severe penal catalogs.

In modern times , Kant and Hegel justified absolute penal theories with the principle of retribution, understood as the principle of retribution , which justify essential aspects of today's normative sentencing :

- Only the proven perpetrator is punishable insofar as he culpably committed the act.

- A punishment must be based on the seriousness of the criminal act: minor bodily harm is punished less than severe, both less than manslaughter, this less than murder.

- The same offenses are to be punished with the same penalty regardless of the person's reputation.

In contrast to the law of German-speaking countries, Anglo-Saxon law has a “punitive damage claim” beyond civil law damages, which is characterized by the idea of atonement and deterrence of other perpetrators and which can be asserted in addition to material damage ( punitive damages ).

Colloquial language and cliché

Contrary to its original intention to rule out revenge and limit violence, the quotation from the Bible is often used without reflection in colloquial language as an expression of merciless retribution. In this meaning it appears today, for example, in media reports on war campaigns, as a novel or film. The corpus linguistics shows which terms are most often associated with the phrase (see chart).

The “vengeful Jew”, who relentlessly follows the alleged Old Testament principle of retaliation “an eye for an eye”, is a classic stereotype of the extreme right , which they use in particular to ward off memories and guilt with regard to the Holocaust , as Jews and Israel are positive for them Stand in the way of identification with the German nation.

The colloquial reception of the phrase is also shown by book and film titles: for example, the novel Eye for an Eye by Anthony Trollope , written in 1879, about a relationship conflict in the Victorian era, or the 1995 film Eye For An Eye by John Schlesinger on the subject of vigilante justice . The novel-like docudrama An Eye for an Eye by John Sack (1993) describes acts of revenge by individual Holocaust survivors against Germans in Stalinist labor camps in Upper Silesia after 1945. Some German reviewers criticized the book in 1995 as a perpetrator-victim reversal. The non-fiction book Eye for Eye - Death Penalty Today (2006) by Silke Porath and Matthias Wippich documents reports of death row inmates in US prisons (see Death Penalty in the United States ).

See also

literature

Rabbinical exegesis

- Ezekiel E. Goitein : The retribution principle in biblical and Talmudic criminal law. A study. J. Kauffmann , Frankfurt am Main 1893. (also dissertation, Halle / Saale 1891)

- Benno Jacob: An eye for an eye. An Inquiry into the Old and New Testament. Philo, Berlin 1929.

Historical-critical exegesis

- Frank Crüsemann : "An eye for an eye ..." (Ex 21,24f). On the social-historical meaning of the Talion Act in the Federal Book . In: Evangelical Theology. New series 47, no. 5, (1987), ISSN 0014-3502 , pp. 411-426, doi : 10.14315 / evth-1987-0505 .

- Klaus Koch: About the principle of retribution in religion and law of the Old Testament. (= Ways of research , 125). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1972, ISBN 3-534-03828-2 .

- Ludger Schwienhorst-Schönberger: The Federal Book (Ex 20.22-23.33). Studies on its genesis and theology. De Gruyter, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-11-012404-1 .

- Susanne Krahe: An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth? Examples of biblical culture of debate. Echter, Würzburg 2005, ISBN 3-429-02669-5 .

- Joseph Norden: "An eye for an eye - a tooth for a tooth". A controversial passage from the Bible. Philo, Berlin 1926. (Reprint: Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation in Wuppertal (ed.), Supporting Association for the Meeting Place Old Synagogue Wuppertal e.V. , Wuppertal 2003, ISBN 3-9807118-4-6 )

Sermon on the Mount

- James F. Davis: Lex talionis in early Judaism and the exhortation of Jesus in Matthew 5.38-42 (= Journal for the study of the New Testament. Supplement series, Volume 281). T&T Clark International, London 2005, ISBN 0-567-04150-6 .

- Susanne Schmid-Grether: An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. Texts from the Sermon on the Mount scrutinized on the Jewish background. JCFV, Schoresch CH 2002, ISBN 3-9521622-6-4 .

Legal history

- Charles KB Barton: Getting even. Revenge as a form of justice. Open Court, Chicago Ill. 1999, ISBN 0-8126-9401-5 .

- William Ian Miller: Eye for an Eye. CUP, Cambridge 2006, ISBN 0-521-85680-9 .

- Kurt Steinitz: The so-called compensation in the Reich Criminal Code. Paragraphs 199 and 233.Schletter , Breslau 1894. (Reprint: Keip, Frankfurt am Main 1977, DNB 204926327 )

Others

- Peter Wetzels, Katrin Brettfeld: An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth? Migration, religion and violence of young people, an empirical-criminological analysis of the importance of personal religiosity for experiences, attitudes and actions of violence by Muslim young people compared to young people of other religious denominations. LIT-Verlag, Münster 2003, ISBN 3-8258-7192-4 .

Web links

Torah exegesis

- Göran Larsson: "An eye for an eye" - The law of damage.

- Marcus Cohn: Jewish criminal law. Retrieved May 10, 2017 (article from the Jewish Lexicon from 1930).

- Yung Suk Kim: Lex Talionis in Exod 21: 22-25: Its origin and context. (English, PDF; 327 kB)

- Manfred Oeming: An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. March 2003.

NT exegesis

- Manfred Schäfer: Renunciation of violence and disengagement.

- Thomas Schirrmacher: Can a Christian go to court? (PDF; 279 kB) In: Additions to Ethics. Martin Bucer Seminar, 2004, archived from the original on September 29, 2007 ; accessed on August 13, 2017 .

- James Davis: Jesus and the Law of Retaliation (Lex Talionis). Matthew 5: 38-42. (English)

- Brigitte Gensch: “An eye for an eye”, not “an eye for an eye”.

- Friedhelm Wessel: An eye for an eye ... A biblical clarification.

Koran exegesis

- H. Ibrahim Hatip: Rights of Victims - in Islam and in Western Legal Systems. A comparative analysis. Archived from the original on February 10, 2005 ; Retrieved August 29, 2006 .

- Michael Muhammad Abduh Pfaff (German Muslim League): How much tolerance can we endure? (PDF) Lecture on the Koranic Talion Law. May 27, 2005, archived from the original on October 27, 2007 ; accessed on August 13, 2017 .

Single receipts

- ↑ The Codex Hammurapi: An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth - early sense of justice .

- ↑ quoted from Frank Crüsemann: An eye for an eye ... (Ex 21:24) . In: Evangelische Theologie 47 (1987), ISSN 0014-3502 , p. 417.

- ↑ Max Mühl: The laws of Zaleukos and Charondas . In: Klio. 22 (1929), pp. 105-124, 432-463.

- ↑ Twelve Tables Act, Table 8: Criminal Law .

- ↑ Quoted from Nechama Leibowitz: An eye for an eye .

- ↑ IV / 8.35; written at 90.

- ^ Bernhard S. Jackson: Essays in Jewish and Comparative Legal History . Brill, Leiden 1975, pp. 75-107.

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud: Treatise Baba Kamma, Chapter VIII, Folio 84a (English) .

- ↑ Benno Jacob: An eye for an eye. An Inquiry into the Old and New Testament. Berlin 1929. Quoted from Brigitte Gensch: "An eye for an eye", not an "eye for an eye"

- ↑ Pinchas Lapide: Reading the Bible with a Jew. LIT, Münster 2011, ISBN 3643112491 , p. 48

- ^ Albrecht Alt: To the Talion formula . In: Kleine Schriften I ; Munich 1968 4 ; Pp. 341-344.

- ^ Hans Jochen Boecker: Law and Law in the Old Testament ; 1984 2 ; P. 150 ff.

- ↑ Frank Crüsemann: An eye for an eye ... (Ex 21,24f) . In: Evangelical Theology. 47 (1987), pp. 411-426.

- ↑ Hans-Winfried Jüngling: An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth: Comments on the meaning and validity of the Old Testament Talion formulas . In: Theology and Philosophy. 59: 1-38 (1984).

- ↑ Ludger Schwienhorst-Schönberger: An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth: To an anti-Jewish cliché . In: Bible and Liturgy. 63: 163-175 (1990).

- ^ Ludger Schwienhorst-Schönberger: Ius Talionis . In: Lexicon for Theology and Church . Volume 5.

- ↑ Eckart Otto: The story of the Talion in the ancient Orient and Israel: Harvest what one sows . In: Festschrift for Klaus Koch. 1991; Pp. 101-130.

- ↑ Martin Hengel: On the Matthew Sermon on the Mount and its Jewish background . In: Theologische Rundschau. 52 (1987), p. 327ff.

- ↑ Wolfgang Stegemann: Jesus and time . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, pp. 290-295.

- ↑ Pinchas Lapide: Living Disenfranchisement? Gütersloher Verlagshaus 1993, ISBN 3-579-02205-9 .

- ↑ Martin Hengel, Anna Maria Schwemer: Jesus and Judaism . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-16-149359-1 , p. 450.

- ↑ John Calvin: Harmony of the Law , Volume III, Commentary on Leviticus 24: 17-22 ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library, original texts in English.

- ↑ Thomas Staubli: Companion through the First Testament. 2nd edition, Patmos, Düsseldorf 1999, p. 139.

- ↑ Thomas Schirrmacher: Can a Christian go to court? (PDF; 279 kB) In: Additions to Ethics. Martin Bucer Seminar, 2004, archived from the original on September 29, 2007 ; accessed on August 13, 2017 .

- ^ Regina Goebel, University of Trier: ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: The criminal law of the Sharia ).

- ↑ Report by Maurice Copithorne, Special Rapporteur for the UN Human Rights Commission, for 1998.

- ↑ Hans Thieme: About the purpose and means of the Germanic legal history. In: JuS . 1975, pp. 725-727.

- ↑ Martin Arends: History of the law. 2006.

- ^ Vocabulary module of the University of Leipzig .

- ^ Fabian Virchow : Against civilism: International relations and the military in the political conceptions of the extreme right. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; Wiesbaden 2006.

- ↑ Dorothea Hauser (Der Spiegel, March 13, 1995): Contemporary history: Too hot to touch? ; Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, Jürgen Zinnecker: Between Forced Labor, Holocaust and Expulsion: Polish, Jewish and German Childhoods in Occupied Poland. Beltz Juventa, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7799-1733-5 , p. 40.