Church history

The church history is a branch of theology and the science of history . It deals with the history of dogmas and the history of Christian theology as well as with the sociological and (ecclesiastical) political development of the churches . This also includes legal , economic , settlement and social-historical aspects as far as they are related to the development of the churches.

The working methods of church historians correspond to the general science of history , the epochs are also assigned the same. The partisan view previously associated with the historian's denominational affiliation only plays a subordinate role today. There are also numerous ecumenical church history projects. Nevertheless, church history is institutionally settled in the theological faculties or institutes of a university . Some controversial theological topics within the history of the Pope, the history of the Council or the history of the Reformation are dealt with more strongly in dogmatics . The fact that research into the history of a particular church (even today) is predominantly carried out by the historians belonging to this particular church is related to the corresponding interest and access to sources. In the German-speaking countries, the history of the Eastern Churches in the Orthodox Churches has been outsourced as a separate part since the Great Schism in 1054 and is not part of general theological training.

overview

The Christianity was born - the Christian year census and the now internationally most widely used calendar accordingly - in the 1st century from the faith of a minority in Palestinian Judaism to the divine sonship of Jesus of Nazareth . Original Christians such as Paul of Tarsus and the Evangelist John also developed this belief using terms from Greek philosophy . Since then, the new religion spread throughout the Roman Empire despite persecution . After the end of state persecution in 311, it later became its state religion and finally - in relation to the number of its believers - the largest world religion of our time. The formation of churches with a hierarchy of officials ( clergy ) was accompanied by dogmatic issues that sometimes led to church divisions and the formation of new denominations .

After 300 years, about 10 to 15 percent of the population of the Roman Empire had become Christian. The theological centers of this expansion were in Asia Minor , Syria and North Africa. After it was first tolerated in the Roman Empire in the time of Constantine and then even became the state religion under Justinian I , it spread so widely within Greco-Roman culture that it was identified with it outside of the Roman Empire. In the late late antiquity its expansion included that of the Roman Empire and some neighboring areas such as Armenia or Ethiopia ; in the Sassanid Empire, too , it slowly spread in the form of the Nestorian belief system.

However, the extensive Christianization of the Roman Empire did not lead to a single Christian culture. In addition to the imperial church with a Latin focus in Rome and a Greek one in Constantinople , there were various Monophysite churches and the Assyrian Church of the East , especially in the Middle East and Egypt, all of which were and remained firmly anchored in the local language and culture.

From the 6th to 10th centuries Christianity experienced its worst setbacks in its history. The Roman Empire collapsed under the Germanic onslaught (see Migration and Late Antiquity ). The original Christian heartlands, the Middle East and North Africa, were overrun by Islam (see also: Islamic expansion ), as were Sicily and Hispania . An expansion of the Western Church , especially in the Frankish Empire , was followed by an absolute low point for the Roman papacy in the 9th and 10th centuries. The eastern branches of the Assyrian Church, which had reached the Empire of China , almost all went down in the Mongol storm .

This decline was followed by an astonishing upswing. In the west, wandering monks and monasteries emanated renewal movements that gradually Christianized the whole of western Europe and united under the Roman Church and won back Spain and Sicily. From Constantinople the Balkans and European Russia were Christianized and new patriarchates developed . The Assyrian Church spread again as a minority religion along the Silk Road to the Chinese coast.

In the late Middle Ages further setbacks followed: Konstantin Opel was the Turks overrun, which until Vienna arrived. In Asia the Christian settlements disappeared apart from a few remains in India . In the West, the papacy was again at an organizational and moral low point, largely due to a great schism , and was partially ousted by humanism , especially in the heartland of Italy .

In the 16th century there was the Protestant Reformation and, parallel to it, a profound reform of the Catholic Church. At the same time, Christianity spread in Latin America . This Catholic spread was followed by a similar worldwide spread of Protestantism by the Dutch and English in North America and Australia in the 17th and 18th centuries . The Russian Orthodox Church expanded into northern Asia , particularly Siberia and Japan . In consequence of colonialism and the Africa mission Christianity eventually spread in many parts of Africa from.

Church history is often divided into four major periods:

- Old church. From the Easter events to roughly the fall of the Western Roman Empire. This also includes the area of patristics.

- Middle Ages. From the fall of the Roman Empire to the time of the Reformation.

- Reformation. From the time of Luther and the Counter Reformation to the Thirty Years War and roughly the beginning of the Enlightenment.

- Modern times. From the Enlightenment until today. The time of the church struggle is a separate topic.

The history of the Eastern Churches is structured differently due to the different history since the secession.

Old church

Early Christianity

Church history begins in the first century with the emergence of a church or congregation of followers of Jesus of Nazareth. The early Christianity or apostolic age refers to approximately the hundred years from 30 AD to about 130 AD.Some churches were still led by apostles and their direct disciples at this time , for example the church in Jerusalem of James the Righteous , the church in Ephesus by the Apostle John and the church in Alexandria by John Mark . Testimonies such as the apparitions of the risen Christ in Galilee (Mk 14.28; Mk 16.7) lead theologians like Norbert Brox to speculate about very early Christian communities that may have existed outside Jerusalem before the crucifixion, “primitive Christianity “So it should not be thought of as an early Christian community in Jerusalem from which the later development started. Under this assumption, early Christianity did not begin on the first feast of Pentecost, but with the first callings of the disciples in Galilee .

Christianity spread quickly through the Greek-speaking “ Hellenists ” to Samaria and Antioch , where the followers of the new religion were first called Christians ( Acts 11:26), then to Cyprus , Asia Minor , North Africa , Greece and Rome . The individual churches were connected to one another by letters and traveling missionaries.

In the 1st century Christianity gradually separated from Judaism , with a sharp cut after the Roman conquest of Jerusalem in 70, and even before that there were disputes between Jewish Christians and Gentile Christians , which essentially concerned how far non-Jewish Christians were are bound by Jewish law. These disputes found a first solution in the apostles' council .

The letters, gospels and other writings of the New Testament were also created during this time and gradually came into liturgical use, parallel to the writings of the Old Testament used from the beginning .

Apostolic Fathers

Apostolic Fathers are the early church fathers who still had direct contact with apostles or were strongly influenced by them.

The sources regarding this time are quite limited. Relatively few texts and biographies have survived.

During this time the church developed into an episcopal church, with the bishops at that time being heads of a local congregation. The New Testament writings circulated in various collections in the churches.

Christianity was gradually perceived by the Roman state as an independent non-Jewish group. There was persecution of Christians under Domitian (81–96) and Trajan (98–117).

Persecution of Christians

The first persecution of Christians and martyrs occurred during internal Jewish disputes with temple priests and Pharisees ( Stephen , James the Elder , James the Righteous ), then also in the Roman Empire ( Simon Peter , Paul of Tarsus) under Nero .

In the time of the Apostolic Fathers, the persecution of Christians fell under Trajan (98–117), who fell victim to Ignatius of Antioch , for example .

His correspondence with Pliny the Younger has survived from the time of Trajan , from which it emerges that the Roman state did not systematically search for Christians of its own accord, but gave people who were reported as Christians the choice of sacrificing to the emperor to bring, that is, to renounce Christianity, or to be executed. However, anonymous advertisements were not taken into account. This resulted in permanent legal uncertainty for Christians, which made them dependent on the goodwill of non-Christian neighbors. The Roman Empire didn't really know how to deal with Christians; it developed no logical procedure: not being a Christian, only remaining a Christian was punished.

During the following decades there was widespread local persecution of Christians, partly by the authorities, partly directly by the population. In such local persecutions of Christians, Polycarp of Smyrna in 155 in Asia Minor and Justin the Martyr in Rome were martyred. Under Marcus Aurelius there were massive persecutions in Lyon and Viennes as a result of several natural disasters.

After the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180, the Christians lived in relative peace until the persecution of Christians under Decius (249-253) and Valerian (253-260). In contrast to earlier, these took place throughout the empire and were aimed at eradicating Christianity. The use of torture to induce apostasy was common. In particular, bishops and priests were killed, Christian property was confiscated, and Christian scriptures were destroyed.

The most massive persecution of Christians took place at the beginning of the fourth century under Diocletian . It was particularly bloody in the east of the empire, in Asia Minor, Syria and Palestine.

Apologists

As a reaction to the persecutions and sarcastic writings of pagan writers ( Celsus ), apologists appeared in the 2nd century who defended the Christian faith in their writings. The most important were Justin the Martyr , Tatian and Athenagoras in the middle of the 2nd century , and Origen and Tertullian in the early 3rd century .

Theological debates in the 2nd century

The most important discussion of young Christianity in the second century was that of Gnosticism , a syncretistic intellectual movement that arose around the turn of the century and was widespread in the Roman Empire , which combined a rich palette of philosophical and cultic traditions and also incorporated Christian traditions, so that a Christian variant of the Gnosis also emerged, some of which have survived, for example the Gospel of Thomas . In contrast to the secret doctrine represented by Gnosis, which is only accessible to the initiated, the Fathers of the Church represented the Apostolic Succession , in which the same doctrine was preached that the apostles had also preached.

Around the middle of the second century Marcion founded his own church, which also partly contained Gnostic ideas and represented a radical distancing from the Jewish tradition. Marcion recognized only a few of the New Testament scriptures, primarily the Pauline letters .

Also around the middle of the second century, Montanus appeared in Phrygia , the founder of Montanism , an ecstatic end-time movement with charismatic features, strict church discipline , asceticism and a ban on marriage .

In response to Marcion's reduction of the New Testament writings and the new legendary or gnostically influenced writings, various lists of writings were created that were officially used in the liturgical context of the Christian communities in communion with one another . From these lists the New Testament canon gradually evolved over the next two hundred years .

Another reaction of the apostolic tradition against the various interpretations of the New Testament was the emergence of " symbols " (baptismal confessions) in which the Christian faith was summarized in short form. One of the earliest surviving confessions is the Old Roman Creed .

Church fathers

From the last quarter of the second century the first important church fathers appeared: Irenaeus of Lyons in Gaul, Tertullian in Africa. The first Christian theological school emerged in Alexandria under Pantaenus and Clemens of Alexandria , which was made famous by Origen for its allegorical interpretation of the Bible.

Cyprian defended the general, inclusive Church against Novatian , who advocated a rigorous excommunication of sinners and apostates.

Eusebius of Caesarea describes in ten volumes the history of the Christian church from its origin to around 324.

Theological questions in the 3rd century

Following the persecution of Decius, the Church was faced with the question of how to deal with Christians who had apostatized under the pressure of persecution - and, more generally, Christians who had sinned badly after being baptized. This question of ecclesiology was to occupy the West in particular for the next 150 years. A faction under Novatian was one of the first groups to call for a rigorous excommunication practice for the sake of the purity of the Church, an attitude that was also represented by the Donatists . In contrast, Cyprian in the 3rd century and Augustine of Hippo in the late 4th century represented a church that, like its founder Jesus Christ, should turn to sinners.

The second question, which was discussed by various sides in the third century, concerned Christology , in particular the relationship of Jesus Christ to God the Father. Sabellius was the most prominent exponent of modalist monarchianism , who took the view that the one God revealed himself successively as Creator, Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit. In contrast, Paul of Samosata and, after him, Lucian of Antioch , who in turn was the teacher of Arius and Eusebius of Nicomedia , represented dynamic monarchianism , which saw Jesus Christ entirely as a person who had been adopted by God at his baptism . Both doctrines were condemned by synods of bishops. However, the christological disputes continued into the 6th century.

In the interpretation of the Bible, two different schools developed, the Antiochene School , which concentrated on the exploration of the actual sense of writing, taking into account the subtleties of vocabulary and grammar, and the Alexandrian School , which, following Origen, had the focus in the allegorical interpretation of the Bible . The contrast between Antioch and Alexandria was to have further effects later in politics and dogmatics.

In the liturgy, sayings from Hippolytus have been handed down that are still in use today in the Orthodox, Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran liturgies, for example the beginning of the Eucharist:

“The Lord be with you

and with your spirit!

Lift up your hearts!

We raise them to master.

Let us give thanks to the Lord our God.

That is worthy and right. "

Imperial Church in the Roman Empire

The greatest persecution of Christians under Diocletian (303-311) ended with Emperor Galerius in 311 passing the Nicomedia Edict of Tolerance , which essentially ended the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. Two years later, Emperor Constantine I and Licinius , Emperor of the East, extended this edict in the Edict of Tolerance of Milan , which guaranteed everyone in the Roman Empire free religious practice.

After the Constantinian turn , the number of Christians, who before the Diocletian persecution comprised around ten percent of the Roman population (probably more in the east, rather less in the west), increased sharply - however, there were also conversions for political reasons during this period, especially in the vicinity of the imperial court, where Christians were strongly preferred by Constantine and his successors - in the fourth century, however, mostly Christians of the Arian tendencies . The attempt of Emperor Julian's (ruled from 361 to 363) to reverse the Constantinian turning point proved to be a failure.

In the media (Time Magazine, Der Spiegel) it is erroneously claimed that Constantine made Christianity the state religion. Although the relationship between Constantine and the Church was very close, it was not until the Emperor Theodosius I issued laws in the years 380 and 390/391 that the Christian faith was prescribed, which historians often interpreted as the elevation of Christianity to the state religion. Theodosius was forced by Ambrose of Milan under threat of excommunication to a public penance of several months for the massacre of Thessaloniki (see the religious policy of Theodosius I ).

His son Arcadius, on the other hand, banished John Chrysostom , the patriarch of Constantinople, when he reproached his wife Eudokia . The Arian-minded Constantius II threatened the bishops at the Council of Milan (355) with the sword in order to get a council decision. In fact, Christianity became the state religion under Justinian I , who represented the unity and close cooperation between the Church (which dealt with divine matters) and the Empire (which governed morality). He is venerated as a saint by the Orthodox Church. The hymns he composed are still used today in the Orthodox liturgy.

Structure of the church

While in the years of persecution there were essentially local churches with local bishops with more or less equal rights who were in communion with one another (or who broke off communion in the event of significant differences in doctrine), a hierarchy of bishops is now developing. Early on, the bishops of major churches had a certain authority over their colleagues, but in the 4th century the bishops of provincial capitals, referred to as metropolitans in the First Council of Nicaea , had a clear leadership role, with the bishops of Alexandria, Antioch, and Rome be specially mentioned. In fact, in the 4th century, the personality of a metropolitan was often more decisive than the rank of the city - bishops such as Ossius of Córdoba , Eusebius of Nicomedia , Basil of Caesarea . Hilary of Poitiers , Ambrose of Milan or Augustine of Hippo played a theological and ecclesiastical role in the church of the fourth century more important than most of their colleagues in Antioch, Rome and Alexandria.

While local synods had already decided on doctrinal issues in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, there were ecumenical councils for the first time in the 4th century - the first council of Nicaea in 325 and the first council of Constantinople in 381 - which, according to the perspective of the time, had the highest authority in Questions of doctrine and church organization came up, although such an authority was by no means always recognized by the losing side.

Monasticism

In response to the increasing secularization of Christianity, there was a sharp increase in monasticism in the fourth century, which referred to the ascetic traditions of early Christianity. In monasticism, too, one can see how Christian life differs in the West and the East. In the east the monks strove for a hermitic life in the desert. In the West, however, Benedict of Nursia developed a coexistence with other monks that avoided ascetic extremes. The basis of such coexistence was the obedience of the individual to the abbot. The monks renounced property and paid attention to the balance between work and prayer. Science was important as work in Benedictine monasteries and so the ancient ideas could be passed on through the schools and clerks in the monasteries over several centuries. One focus was Egypt, where Antony the Great and Pachomios founded the first hermit communities or monasteries at the beginning of the 4th century; others formed in Asia Minor, greatly encouraged by Basil of Caesarea . In the west, monasticism spread in the 4th century through Johannes Cassianus and Martin von Tours in Gaul, from the 5th century through Patrick of Ireland in Ireland and Scotland, in the 6th century through Benedict of Nursia in the area of the Roman Empire.

Christology and the Trinity

The question of the Trinity (threefold) of God gained importance in the early phase of Christianity. A group of Arian Christians referring to the presbyter Arius took the view that God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are not of the same essence (Greek ὁμοούσιος), but that the son and spirit are only similar to the Father (Greek ὁμοιύσιος). From the Arian point of view, only the Father was God. Spirit and Son exist from the beginning, but created by God and thus only images of God.

This question about the figure of God also touched on the quality of Christianity as monotheism and was therefore of central importance for early Christianity.

Non-Chalcedonian churches

The Assyrian Church of the East separated from the other churches in the Nestorian dispute at the Council of Chalcedon (451), but without actually advocating Nestorianism.

The Nestorians were the predominant Christian church in the Persian Empire and under the Abbassids. It was Nestorian Christians who translated the ancient Greek philosophers into Arabic at the courts of the caliphs, who centuries later came from the Arabs into the European Middle Ages. The Nestorians were very active in mission: there were many Nestorian congregations and bishops along the Silk Road and in 635 they came to China, where they founded monasteries and appointed a metropolitan. By the millennium, however, these communities had given way to Islam and Buddhism. Only in southern India and Ceylon did Nestorian communities survive.

The Miaphysite churches, u. a. The Coptic Church and the Armenian Apostolic Church did not recognize the decisions of the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451 and then separated. The reasons for this were partly theological and partly political.

The patriarchates of Alexandria (including Ethiopia) and Jerusalem were largely Miaphysite and renounced the imperial church, even if there were parallel minorities everywhere who stayed with the imperial church.

The Armenian Church continued to exist under the rule of the Sassanids and Arabs and contributed significantly to the Armenian identity and had its own literature and architecture, numerous monasteries and schools and its own art direction. It spread mainly through Armenian colonies and traders.

middle Ages

Byzantine imperial church

Hesychasm

brown : up to 600; green : up to 800; red : up to 1100; yellow : up to 1300

Hesychasm is a form of spirituality that was developed by Orthodox Byzantine monks. Its starting point is the behavioral rules of late ancient monasticism. With it the ideas of serenity and inner peace are connected. Persistent practice within the framework of a special prayer practice serves to achieve hesychia. The praying hesychasts repeat the call to God of the Jesus prayer over long periods of time. The medieval Hesychastic movement had its center in the monasteries and skiing on Mount Athos . In its heyday in the late Middle Ages, it also spread to the northern Balkans and Russia. After the destruction of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottomans in the 15th century, hesychastic practice in the former Byzantine areas took a back seat. The tradition did not break off, however, and was also continued in early modern Russian monasticism.

Christianization of Europe

Roman Catholic Mission

The Latin-speaking countries of Western Europe belonged to the Christianized Roman Empire. Even after the collapse of the Western Empire, the majority of the population remained in the Roman Catholic Orthodox faith, even where they were temporarily ruled by Arian Germanic tribes during the Great Migration .

Iro - Scottish monks and the influences of Rome played a prominent role in the early medieval proselytizing of Central Europe around the 6th century . It was promoted by the missionaries Gallus , Columban , Bonifatius and Kilian , among others , although this activity was by no means safe. Charlemagne defeated the Saxons in northern Germany around 800 and issued the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae .

When the Christianization of a region or a group was completed and from when the pre-Christian cults continued only in customs and superstition, can usually hardly be determined exactly.

Orthodox mission

The Christianization of Eastern Europe essentially took place from Constantinople .

Photius I sent the first missionaries to Russia in the ninth century. In the middle of the tenth century there was a Christian church in Kiev and the Grand Duchess Olga of Kiev was baptized. It was only under her grandson Vladimir I (960-1015) that there was a mass conversion of Kiev and the surrounding area. In 991 the population of Novgorod was baptized. When Vladimir died in 1015 there were three dioceses in Russia. In the twelfth century, Christianity spread along the Upper Volga . The mission was primarily carried out by monks and numerous monasteries were founded.

The peoples of the Baltic States , the Prussians , Wends , Latvians and other Baltic tribes , as well as the Estonians , were not forcibly Christianized until the 10th to 13th centuries as part of the German settlement in the east , whereby the Grand Duchy of Lithuania could not be conquered and only became part of the 14th Converted to Christianity in the 20th century.

Oriental schism

By the middle of the 9th century , despite all these differences, the Eastern and Western Churches were in full communion with one another. The first serious conflict arose in 862. Pope Nicholas I convened a council in Rome in 862, which deposed Patriarch Photios of Constantinople and conveyed this decision in the tone of an absolute ruler to Constantinople, where he was ignored by the patriarch and the emperor. Photios was very involved in the Slav mission - he sent Cyril and his brother Methodius , the two Slav apostles , to Moravia. The conflict between him and Rome arose when Pope Nicholas I supported Frankish missionaries in Moravia who taught the creed with the filioque introduced in Spain - so far Rome had been neutral or even against the filioque question. Photios, a brilliant theologian, countered with a sharp encyclical and convened a council in Constantinople, where Nicholas was excommunicated.

There had been further turning points between the Eastern and Western Churches, including:

- allegedly at the establishment of the East Franconian-German Empire by Otto I ( 962 ),

- then the "schism of the two Sergioi" Pope Sergius IV. (1009-1012) and Patriarch Sergius II. (1001-1019), in the years 1011 / 1012 .

The break occurred when the Normans conquered the previously Byzantine and largely Greek-speaking southern Italy over a period of several decades in the 11th century . Pope Leo IX promised help to the Byzantine governor of the province, on condition that the previously eastern churches in this area should adopt the western rite . The governor agreed, the clergy in no way. The imperious Cardinal Humbert von Silva Candida , leading theorist of absolute papal rule, was sent to Constantinople as envoy. However, he did not even try to resolve the conflict: he denied the title of ecumenical patriarch, doubted the validity of his ordination , insulted a monk who defended Eastern customs, etc. In the end, on July 16, 1054, Humbert laid a bull with the excommunication of Kerullarios and other Orthodox clergy on the altar of Hagia Sophia . In this bull the Orthodox Church is referred to as the "source of all heresies". After Humbert's quick departure, he and his companions were in turn excommunicated by Kerullarios and a council (Humbert and companions, not the Pope). The remaining Eastern Patriarchs clearly sided with Constantinople and also rejected Rome's claims.

Cluny abbey reform

From the Cluny Abbey went to the early 10th century from a comprehensive reform movement. The main ideas of the reform were strict observance of the Benedictine Rule and the deepening of the piety of the individual monk in connection with a reminder of the transience of the earthly . In addition, there was a reform of the monastery economy and the detachment of the monasteries from the bishops' claim to rule; the monasteries were placed directly under the protection of the Pope.

The Investiture Controversy

The investiture controversy describes the escalation of the rivalry between ecclesiastical (papacy) and secular (imperial or kingdom) power in the High Middle Ages. Specifically, it was about the appointment of clergy - so-called investiture - by secular power. From 1076 onwards, the ( Hoftag in Worms ) escalated between Gregory VII, known as the reform pope, and Henry IV. Gregory asserted his claim to power against King Heinrich by deposed him in 1076, thus causing the defection of most of the German bishops and princes . This provoked Heinrich's penitential walk to Canossa in 1077 , whereupon he was reinstated. After half a century of conflict, in which u. a. came to the appointment of an antipope by Heinrich, the Worms Concordat in 1122 brought the solution to the conflict: The German emperor had to renounce the investiture of the pope, but was still allowed to be present at the election of bishops and to give speeches.

Crusades

The crusades were religiously motivated wars between 1095/99 and the 13th century started by Christians in the west. In a narrower sense, the Crusades are only understood to mean the Orient Crusades that were conducted at this time and that were directed against the Muslim states in the Middle East . After the First Crusade , the term "crusade" was expanded to include other military actions that did not target the Holy Land .

Age of Reformation

In the Middle Ages, numerous innovators rebelled against a morally depraved church. They wanted to correct the erroneous history (Latin corrigere ), restore the early church ( restituere ), renew an encrusted doctrine ( renovare ) and redesign the ecclesiastical offices ( reformare ).

Lutheran Reformation

Martin Luther (1483–1546) was the theological originator of the Reformation. As a professor of theology belonging to the Augustinian hermits, he rediscovered God's promise of grace in the New Testament and henceforth oriented himself exclusively to Jesus Christ as the “Word of God made flesh”. According to this standard he wanted to overcome undesirable developments in the history of Christianity and in the church of his time.

His emphasis on the gracious God, his sermons and writings and his translation of the Bible, the Luther Bible, changed the society dominated by the Roman Catholic Church in the early modern period. Contrary to Luther's intention, the church split, the formation of Evangelical Lutheran churches and other denominations of Protestantism.

See also: Philipp Melanchthon and Magdeburg Centuries

Reformed Calvinist Reformation

Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) was the first Zurich reformer. While Luther only wanted to remove grievances in the church that contradicted his understanding of the Bible (e.g. the indulgence trade ), Zwingli only accepted in the church what was expressly in the Bible. In the Marburg religious discussion (1529) between Luther and Zwingli, the biblical foundations of the doctrine of the Lord's Supper were discussed. Despite smaller approaches, however, it was not possible to move the previously irreconcilable positions towards one another.

The theology of Zwingli was continued in the second generation by Heinrich Bullinger (1504–1575). With the Consensus Tigurinus between Bullinger and Johannes Calvin (1509–1564), the reformer who worked in Strasbourg and Geneva, the Reformed churches came into being .

In addition to the Reformed churches, Calvinism also had a more or less strong effect on almost all other churches in the Anglo-American region. The Church of England's Creed , the 39 articles , is mainly influenced by Calvin. The same applies to the Baptists and Methodists .

Anglican Reformation

The Anglican national churches see themselves as parts of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church, which are committed to the tradition and theology of the English (and partly Scottish) Reformation. However, the Anglican Church understands its “Reformation” not as a break with the pre-Reformation Church, but as a necessary reform of the Catholic Church in the British Isles. This means that the Anglican Church is both a Catholic Church and a Reformation Church, although since the Reformation it has developed a consciously independent Christian-Anglican tradition and theology.

In Anglican doctrine there is a wide spectrum between the High Church ( Anglo-Catholicism ), which is close to the other Catholic churches in liturgy and teaching, and the Low Church , which is close to Protestantism , especially Calvinism .

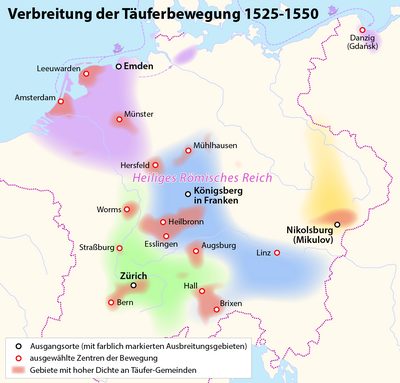

Radical Reformation and Anabaptists

Thomas Müntzer combined the reform of the church with the demand for a revolutionary upheaval in political and social conditions. This is where the theological roots of the German Peasants' War lay , which Martin Luther rejected. The Eternal Council was also founded in Thuringia to enforce the political and social demands of the peasants.

The Anabaptists formed an important movement within the Reformation. Their reputation was soon overshadowed by the radical Anabaptist Empire of Munster , which ended in 1535. The baptism of believers practiced exclusively by them , which their opponents misleadingly called rebaptism , was the result of their ecclesiology . For them, “church” was the community of believers in which social barriers had fallen. They practiced the common priesthood and democratically elected their elders and deacons within the wards. They advocated the separation of church and state and demanded general religious freedom (not just for themselves). Many of them refused to do military service and to take the oath . These include the Hutterite and Mennonite religious communities that still exist today .

Another group of the radical Reformation formed the anti-Trinitarians who, like the Anabaptists, were persecuted by the state and other churches. There was also some overlap between Anabaptist and anti-Trinitarian approaches. The Unitarians initially only formed permanent churches in Poland-Lithuania and Hungary-Transylvania. Today there are Unitarian churches all over the world, although some of them have opened up to non-Christian views.

The group called "enthusiasts" by its opponents was less tangible in its structures . The spiritualists were related to the Anabaptist movement and partly arose from it. They represented a deeply internalized belief. Its primary goal was not to form a visible and authoritative church. Sebastian Franck and Kaspar Schwenckfeld were among its important representatives . There is still a Schwenkfeld Church founded by German immigrants in the USA today .

The groups mentioned were persecuted with great severity by the Catholic, Lutheran and Reformed authorities - regardless of their different goals and teachings. Thousands of peaceful Anabaptists have been imprisoned, tortured, and burned alive or drowned for their beliefs. One speaks therefore - parallel to the genocide - meanwhile also of an ecclesiocide , which was perpetrated on the Anabaptists.

Catholic Counter-Reformation

Counter-Reformation is the general term used to describe the reaction of the Roman Catholic Church to the Protestant Reformation that took place in the field of Catholic theology and the Church.

The term Counter-Reformation also describes a process within the Roman Catholic Church, which tried in the course of the Council of Trent from around 1545 to push back the Protestantism, which was both politically and institutionally established.

Witch hunt

In the late Middle Ages and especially in the early modern period, women and men were repeatedly accused of being witches or sorcerers. In the witch trials, the defendants usually had no real chance of proving their innocence. The judgments were mostly based on denunciation and confessions obtained under torture. The convicts were usually burned at the stake. They were also often forced to denounce alleged accomplices on their part. Witch hunts were pursued by both church authorities and government officials. Even if they were justified religiously, they cannot simply be traced back to the churches. Often the local population also contributed.

In the older research discussion, the number of victims of several million people assumed has been significantly reduced today due to the better source situation; tens of thousands of witches and sorcerers were executed. There are clear regional focuses. Waves of persecution occurred especially in the Alpine region and in Central Europe. In southern Germany, for example, a number of bishops emerged in the late 16th century. In contrast, in Spain, for example - despite the very powerful Inquisition there - there were almost no executions.

Modern times

Main development

In modern times, all churches are essentially developing separately.

Lutheran Orthodoxy

The phase of Lutheran Orthodoxy follows on from Martin Luther's work and the Reformation and describes the phase of consolidation of Lutheran theology, from around 1580 to 1730. It is characterized by the development of extensive and small-scale teaching systems and dogmatics , such as those of Martin Chemnitz and Johann Friedrich König or Abraham Calov . During the High Orthodoxy, the dogmatic approach changed from the Loci method, which goes back to Melanchthon , to the analytical Ordo method, which goes back to the theological Aristotelianism . Lutheran orthodoxy was replaced in many places by Pietism and the Enlightenment, but was revived in the Neo-Lutheranism of the 19th century.

Pietism

Pietism is the most important piety and reform movement of Protestantism after the Reformation. Pietism was influenced by mystical spiritualism , English puritanism , the works of Luther, and Lutheran orthodoxy . The term established itself towards the end of the 17th century, in the course of the conflict between Lutheran orthodoxy and Philipp Jakob Spener and his followers. In Halle Pietism these represented the internalization of religious life with conversion and rebirth , the development of personal piety with new forms of communal life and detachment from the authorities. Spener's Pia desideria from 1675 served as the programmatic script. At the height of development around 1700, August Hermann Francke tried to push through the renewal movement from Halle against Orthodoxy and the Enlightenment. From 1740 onwards, the Württemberg pietism spread . The Herrnhuter Brethren , founded in the 1720s by Nikolaus Ludwig Graf von Zinzendorf , is also counted as Pietism .

enlightenment

The Enlightenment considerably weakened Christianity politically in the 17th and early 18th centuries. The most significant change was the partial distance between church and state. Since then it has been possible in many countries to openly reject the views of the respective church or to resign from the church. The criticism of religion that grew with the Enlightenment and its results cannot, however, be limited to the process of secularization. In addition to secularization, religious movements also emerged from the 17th century, which critically questioned the dogmas of the official churches and instead developed their own forms of belief, such as Pietism. The individual connection of the believer to God moved more and more into focus. In the course of the Enlightenment, neology , a radical criticism of dogma and the Bible, developed. Its main representative, Johann Salomo Semler, is considered the founder of the historical-critical method . The Roman Catholic Church was opposed to this method until the Second Vatican Council . Gotthold Ephraim Lessing noted in the course of the fragmentation dispute as a “nasty wide gap” between accidental historical truths and necessary historical truths.

Roman Catholic Church of the Modern Era

After the upheavals of the Enlightenment, the Roman Catholic Church also had to adapt to social reality. The time of the ecclesiastical principalities ended in Germany with the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss 1803. In the restoration phase , the Roman Catholic Church was on the conservative side of the restorers and anti-modernism . This culminated in the First Vatican Council , at which the infallibility dogma was formulated in 1870 . This led to the secession of the Old Catholics , who rejected the infallibility of the Pope. During the industrialization , the Roman Catholic Church criticized the inhuman exploitation of the workers and Pope Leo XIII. formulated an extensive social doctrine .

At the time of the First World War , the Roman Catholic Church tried to remain neutral. In 1933 Pius XI signed the Reich Concordat , which regulated the relationship between the Roman Catholic Church and the German Empire. The Second Vatican Council from 1962 to 1965 marked the beginning of tentative but extensive modernization measures and the opening towards modernity.

Individual side developments

Christianity worldwide

In the 16th century, Christianity spread more than ever in Latin America and along the coasts of Africa and Asia through the monastic orders that followed the Spanish and Portuguese explorers . This Catholic spread was followed in the 17th and 18th centuries by a similar worldwide spread of Protestantism by the Dutch and English and by emigrants who belonged to Protestant minority denominations . The Russian Orthodox Church expanded into northern Asia , particularly Siberia and Japan .

In the 19th century, Protestantism spread throughout North America, was the dominant religion in Australia , expanded in Latin America, and had missions in almost every African and Asian country.

In the 20th century the focus of Christianity shifted again. The heartland of the Protestant churches was now the United States . By 1965 Christians were split equally between Western and non-Western countries, and in the decades that followed, Third World Christians became the majority. New, local churches of the charismatic direction - not the traditional churches - had a particular boom there .

Ottoman Empire

The Oriental Christians were integrated into the Millet system in the Ottoman Empire and enjoyed a certain autonomy against payment of a special tax, during which the Christian churches were represented as an ethnic group at court. The Orthodox churches were seen as a common patriarchate that was dominated by the Greeks, which contributed to the independence of the Slavic peoples under Ottoman rule. The Millet system has survived in a little changed form in some of the successor states of the Ottoman Empire (not including Turkey).

Ecumenical and interchurch cooperation

The ecumenical movement ideally strives for worldwide unification and cooperation between the various Christian churches. Its institutional form is above all within the framework of the World Council of Churches . Various global and local working groups have also been set up. They include the Worldwide Evangelical Alliance , the Conference of European Churches , the Association of Evangelical Free Churches and the Working Group of Christian Churches in Germany .

time of the nationalsocialism

Protestant church

On July 23, 1933, the German Christians won a landslide victory in the church elections with National Socialist support. Their illegal actions in the usurpation of the Protestant church leadership and the spread of false doctrines called the Confessing Church (BK) on the scene. On May 31, 1934, the latter presented their objection in the Barmen Theological Declaration at the first nationwide Confessional Synod .

After the Dahlem Confession Synod of October 1934, the Reich Brotherhood Council was set up on November 22, 1934 by a “Provisional Church Administration” (VKL) of the German Evangelical Church . This VKL turned to the Führer and Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler with its Gravamina on April 10, 1935 .

The 3rd Confessional Synod of the Evangelical Church of the Old Prussian Union , which met on September 26, 1935 in Berlin-Steglitz, impressively defended itself in its message to the congregations, The Freedom of the Bound, against state attacks.

On May 28, 1936, Wilhelm Jannasch handed a letter of protest from the second provisional leadership of the German Evangelical Church to Chancellor Hitler in the Reich Chancellery "into the hands of the then State Secretary Meißner ".

The increasing rejection of a “ positive Christianity ” by ideological forces around Alfred Rosenberg , who promoted the myth of the 20th century , led to the declaration of the 96 Protestant church leaders against Alfred Rosenberg because of his writing Protestant Rome Pilgrims on Reformation Day 1937 .

In 1939, with the approval of three-quarters of the leadership of the German Evangelical Churches (now predominantly dominated by German Christians), the Eisenach " Institute for Research and Elimination of the Jewish Influence on German Church Life " was founded. This institute had the main task of compiling a new “people's testament” in the sense of the “Fifth Gospel” demanded by Alfred Rosenberg in the myth of the 20th century , which was supposed to proclaim the myth of the “Aryan Jesus”. Thanks to the opposition of the Confessing Church, this new type of “Bible” did not have the success hoped for by the German Christian founders (and partly also promoted by Confessional Christians). In the processing of this people's will, consideration was also given to biblical criticism of the time (removal of a wage penalty morality and other things). These aspects and this phase of the evangelical church history and Christianity history have not yet been dealt with historically.

The merit of the Confessing Church, its historical achievement, can best be described as the church historian Kurt Dietrich Schmidt did it succinctly and impressively in his great church fight lecture shortly before his death in 1964:

- “If this natural national and racial religion had triumphed” - with its blood and soil ideology, with its theological justification of the Nazi state as a new revelation of God, with its God in the depths of the German soul, with its abolition of the old Testament and essential parts of the New Testament, with their rejection of so-called world Protestantism, i.e. ecumenism, if this religion had triumphed on a broad front and overrun the entire Protestant church - “it would be about the being of the Protestant church in Germany had happened. So this is the first and probably also the greatest thing that the initially small minority, which then became the BK, achieved, that the Protestant Church remained 'Church' ... It was only a small minority who started with the slogan ' The church must remain the church, and through much misunderstanding, disgrace and suffering it has had to prove this slogan. Therefore it is indeed something great that she has achieved 'her goal' ”.

And the philosopher Volker Gerhardt sums up the outcome of the church struggle as follows:

- " Resistance to the attempted extermination of faith by a totalitarian policy is one of the most important theological events of the 20th century."

Roman Catholic Church

Before the seizure of power , the German episcopate distanced itself from National Socialism by forbidding Catholics to become involved in the NSDAP and forbidding NS associations to march in church processions . In 1932, all dioceses in the German Reich felt compelled to declare membership of the NSDAP “incompatible with the Christian faith”. In the predominantly Catholic Rhineland and in Bavaria , the NSDAP hardly achieved more than 20 percent of the votes cast, compared to sometimes over 60 percent in Protestant regions.

After Hitler expressed himself church-friendly several times and in his government declaration on March 23, 1933, described the two large Christian churches as “the most important factors in maintaining our nationality”, the Catholic Church relativized its previous criticism. The bishops withdrew their incompatibility resolutions. On July 20, 1933, the Curia surprisingly concluded the Reich Concordat.

Free Churches

The patriotic attitude of many Germans at the time also existed among the members of the free churches. In addition, the Hitler government was seen as a bulwark against the dangers of Soviet communism . The free churches had few members compared to the large popular churches. Thus, from the outset, they saw themselves not in a position to issue influential statements, even if they noticed questionable events. Because of this small size, the free churches were rather insignificant for National Socialist control bodies such as the Gestapo , so that they had some freedom in their worship services. It was even possible that a Baptist preacher like Arnold Köster often criticized features of the National Socialist worldview .

See also

Web links

- "Association of Church Archives in the Working Group of Archives and Libraries in the Protestant Church" (AABevK)

- VKWB - an amalgamation of around 100 ecclesiastical academic libraries of the Protestant regional churches and other ecclesiastical institutions in Germany and Switzerland. Book inventory totaling around four million volumes

literature

- See also the literature on the individual main articles. For church history, see Church history (literature) .

swell

- Adolf Martin Ritter (Ed.): Church and theology history in sources . Vol. 1: Old Church & Vol. 2 Middle Ages, 8th edition. Neukirchen-Vluyn 2007-2008.

- Volker Leppin (Ed.): Church and theology history in sources . Vol. 3: Reformation, 2nd edition. Neukirchen-Vluyn 2005.

- Martin Greschat (Ed.): Church and theological history in sources . Vol. 4: From denominationalism to modernity. Neukirchen-Vluyn 2008.

- Martin Greschat (Ed.): Church and theological history in sources . Vol. 5: The Age of World Wars and Revolutions. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1999.

introduction

- Georg Denzler , Carl Andresen : Dictionary church history . dtv, Munich 1982; 5th updated edition 1997; Licensed edition Matrix, Wiesbaden 2004.

- Manfred Heim : Small encyclopedia of church history . CH Beck, Munich 1998.

- Edward Norman: History of the Catholic Church. From the beginning until today . Theiss, Stuttgart 2007.

- Bernd Moeller : History of Christianity in Basic Features . 10th edition. UTB, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 3-8252-0905-9 .

- Lenelotte Möller , Hans Ammerich : Introduction to the study of church history. WBG (Scientific Book Society), Darmstadt 2014 (introduction to theology), ISBN 978-3-534-23541-4 , 160 pp.

- Wolfgang Sommer , Detlev Klahr: Church history revision course . 5th edition, UTB, Göttingen 2012.

Lexicons

Basic information on individual topics and people can usually be found in general theological and other relevant dictionaries, including:

- Theological real encyclopedia ,

- Lexicon for Theology and Church ,

- Religion past and present ,

- Biographical-Bibliographical Church Lexicon ,

- Dictionnaire d'histoire et de geographie ecclésiastiques ,

- Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity ,

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas ,

- Historical Dictionary of Philosophy ,

- Pauly-Wissowa .

- The scientific Bible dictionary on the Internet

Manuals

- Raymund Kottje , Bernd Moeller (Ed.): Ecumenical Church History. Matthias Grünewald Verlag, Mainz 1970 (3 volumes).

- Thomas Kaufmann , Raymund Kottje, Bernd Moeller, Hubert Wolf : Ecumenical Church History. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2007/08 (3 volumes).

- Karl Heussi : Compendium of Church History. 18th edition, Tübingen 1991.

- Norbert Brox : Church history of antiquity . 3rd edition Patmos, Düsseldorf 2006.

- Isnard Wilhelm Frank : Church history of the Middle Ages . Patmos, Düsseldorf 2008.

- Heribert Smolinsky , Klaus Schatz: Church history of the modern age. Patmos, Düsseldorf 1993, ( Guide Theology. 21, 2 volumes).

- Carl Andresen : Handbook of the history of dogmas and theology. 2nd Edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1999.

- Wolf-Dieter Hauschild : Textbook of church and dogma history in 2 volumes. Gütersloh publishing house, Gütersloh 1999.

- Johannes Wallmann : Church history in Germany since the Reformation. 6th edition, UTB, Tübingen 2006.

Rows

- History of Christianity ("Blue Series") Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1975.

- Ulrich Gäbler , Johannes Schilling (Hrsg.): Church history in individual representations ("black row"), 39 volumes. Evangelical Publishing House, Leipzig.

- Martin Greschat (Hrsg.): Gestalten der Kirchengeschichte , 14 volumes. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1993.

- History of Christianity , 14 volumes. Herder Verlag , Stuttgart 2004.

- Approaches to church history . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1987 ff.

Individual evidence

- ^ Norbert Brox: Church history of antiquity , 3rd edition, Düsseldorf 2006, p. 10.

- ↑ Cf. Möller, Geschichte des Christianentums in Grundzügen , 8th edition. Göttingen 2001, pp. 154-161.

- ↑ Burkhard Weitz: What does the Reformation mean? . In: chrismon special. The Protestant magazine for Reformation Day, October 2012. Retrieved on March 31, 2013.

- ↑ cf. the essay by Wolfgang Krauss : Growing from the roots - Telling our story further ( Memento from September 19, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Following the Protestant historian Leopold von Ranke

- ^ Albrecht Beutel : Enlightenment in Germany . Göttingen 2006, p. 213, p. 232; Kaspar von Gruyeres : Religion and Culture. Europe 1500-1800 . Gütersloh 2003, p. 291, p. 297; Hartmut Lehmann : Religious Awakening in Time Far from God: Studies on Pietism Research . Göttingen 2010, p. 7; Annette Meyer: The Age of Enlightenment . Berlin 2010, p. 147.

- ^ Johannes Wallmann : Church history of Germany after the Reformation , 6th edition. Tübingen 2006, p. 161.

- ↑ Printed in: Kurt Dietrich Schmidt (Ed.): Documents des Kirchenkampf II / 1 , Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 1964, p. 705 f. geschichte-bk-sh.de: The freedom of the bound - message of the 3rd Synod of Confession of the Evangelical Church of the Old Prussian Union to the communities of September 26, 1935

- ↑ Online at geschichte-bk-sh.de

- ^ Wilhelm Jannasch: German Church Documents. The attitude of the Confessing Church in the Third Reich , Zollikon-Zurich: Evang. Verlag 1946, pp. 20–31 (in long version, but without IV. “Deconfessionalization” and without appendices). Copy of the original version (without attachments): online at geschichte-bk-sh.de .

- ↑ August Marahrens , Friedrich Müller , Thomas Breit : Declaration against Rosenberg (October 31, 1937) , in: Joachim Beckmann (Hrsg.): Kirchliches Jahrbuch für die Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland 1933–1944 , Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn 2nd edition 1976, Pp. 211–213 (online at geschichte-bk-sh.de) . Under the title The declaration of the 96 Protestant church leaders against Alfred Rosenberg first printed in: Friedrich Siegmund-Schultze (Hrsg.): Ökumenisches Jahrbuch 1936–1937 , Zurich and Leipzig: Max Niehans 1939, pp. 240–247. This yearbook also contains a presentation of the development of the situation in the German Evangelical Church from 1935 to 1937 , written in 1938 by an unnamed emeritus theologian of the Confessing Church (p. 224–239; online at geschichte-bk-sh.de ) .

- ↑ Members of the Confessing Church also temporarily advocated such an approach in the hope that at least this would put a stop to the church leaving movement from 1937 to 1940 and persuade people to remain in the churches.

- ↑ See for example the history workshop: The Confessing Church in Schleswig-Holstein and its impulses for the design of the church after 1945 with detailed sources and references to the processing of this phase of church history in a federal state (online at geschichte-bk-sh.de ).

- ^ Kurt Dietrich Schmidt: Introduction to the history of the church struggle in the National Socialist era. [A series of lectures, typewritten. 1960, with handwritten corrections until 1964; posthumously] edited and provided with an afterword by Jobst Reller, Hermannsburg: Ludwig-Harms-Haus 2nd edition 2010, p. 257 f. Quoted from: Karl Ludwig Kohlwage : The theological criticism of the Confessing Church of the German Christians and National Socialism and the importance of the Confessing Church for the reorientation after 1945 , printed in: Karl Ludwig Kohlwage, Manfred Kamper, Jens-Hinrich Pörksen (eds.) : "What is right before God". Church struggle and theological foundation for the new beginning of the church in Schleswig-Holstein after 1945. Documentation of a conference in Breklum 2015. Compiled and edited by Rudolf Hinz and Simeon Schildt in collaboration with Peter Godzik , Johannes Jürgensen and Kurt Triebel, Husum: Matthiesen Verlag 2015, ISBN 978-3-7868-5306-0 , p. 34.

- ↑ Volker Gerhardt: The sense of the sense. Experiment about the divine , Munich: CH Beck 2014, p. 336.

- ^ Writings of the initiative group of Catholic lay people and priests in the Diocese of Augsburg e. V .: The struggle for the school cross during the Nazi era and today ( Memento from August 24, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) 1st edition 2003, Prof. Dr. Konrad Loew

- ^ Deutsches Historisches Museum: Churches in the Nazi regime