Brocken witch

Brocken witches are fictional figures of popular belief who are connected to the Brocken through their supposed gatherings on the Brocken , especially on the Witches Sabbath on Walpurgis Night . The legends about witches meeting, which take place in places called Blocksberg , are said to have their origin in Slavonic .

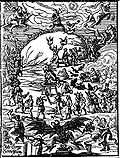

Up until the first half of the 16th century, the mountain was only occasionally referred to as "Blocksberg" and a place for witch meetings. Since the second half of the 17th century, the Brocken has been the main meeting place for witches from all over Germany . The dissemination and popularization of the Brocken as a mountain of witches came about primarily through the popular work Blockes-Berg's Verführung (1668) by Johannes Praetorius ; through Goethe's Faust. In a tragedy (1808), which Praetorius' book used, the motif of the witch's dance became part of national education on May 1st. The educational tourism initiated by Praetorius and then especially by Goethe has led to annual Walpurgis Night festivities including the sale of relevant souvenirs since the Brocken was opened up for traffic .

Development in literature

A poem from the year 1300 is about ghost beings who drive to the "Brochelsberg" and have their meeting there. It should be noted, however, that the term "witch" has only spread since the 16th century.

The idea of a witch's sabbath on the Brocken has appeared in learned treatises since the 16th century. The authors include the Greifswald doctor and professor Franziskus Joel in 1580 and the denial of this idea by the Rostock lawyer Johann Georg Gödelmann in 1592 .

At the beginning of the 17th century, the Brocken received greater popularity as a witch mountain through Mons Veneris from Heinrich Kornmann. The most important work of this time is Blockes-Berg's performance by Johannes Praetorius in 1668. He also made the name Blocksberg popular for the Brocken. In the last third of the same century, the Brocken was known as Hexenberg as far as German-speaking Switzerland . With this importance, it gained further dissemination through travel literature.

Since the 18th century, more and more literature about Walpurgis Night appeared on the Brocken. Johann Friedrich Löwen combined in his work Die Walpurgis Nacht in 1756 . A poem in three chants the Walpurgis celebration for the first time with the Fauststoff . In almost all books about the Harz from the 18th century, there are at least mentions of witch meetings on the Brocken. The Brocken also appears as a meeting place for witches in reference works such as the Large Complete Universal Lexicon by Johann Heinrich Zedler and the Complete Geography by Johann Hübner .

Through Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's work Faust. A tragedy from 1808, which contains a scene of a Walpurgis Night, increased the popularity of the witches on the Brocken considerably. Through this work he became known as Hexenberg outside of Germany.

Finally, in the 20th century, the myth of the witch's meeting on the Blocksberg was popularized in a friendly way by children's books such as Die kleine Hexe by Otfried Preußler or the radio play series Bibi Blocksberg .

Witch hunt

The Harz formed a focus of the witch hunt in the region of what is now Saxony-Anhalt . The Brocken had an outstanding supraregional importance as a witches' meeting place. Even before Goethe published his work Faust I , the mountain was considered a meeting place for witches.

In 1540, in a protocol of a regional witch trial, the time Walpurgis Night appears for the first time in addition to the location Brocken. Further statements of this kind can be found above all in trials at the end of the 16th and 17th centuries. However, until the first half of the 17th century, the mountain had not yet established itself as a witch's mountain with far-reaching importance. Up to the second half of the 16th century, the Venusberg , the Heuberg and the Staffelberg were named with a similar meaning alongside the Brocken . When the witch trials were abolished in the 17th century, the fables of Walpurgis Night gained in importance and spread.

Real place of worship

Since the beginning of the 18th century, the Brocken has been associated in literature with old cult sites of real festivals. At the end of the same century this view took hold; they still serve to explain the Witches' Sabbath to this day.

It is described how the Saxons pursued pagan sacrificial festivals despite being Christianized by Charlemagne . They did this in remote places so as not to attract attention. After Charlemagne found out about this, he had Christian guards set up to control the activities, especially on festive days. However, the Saxons disguised themselves in order to drive away the guards and to be able to carry out their rituals. The guards then spread rumors about figures flying to the Brocken at night.

With this depiction it was initially controversial that the Saxons disguised themselves and expelled the guards. The fact that there were pagan festivals at least before Christianization was recognized until the end of the 20th century. As early as the 19th century, some authors questioned whether the Brocken ever served as a pagan place of worship, as the weather conditions on the mountain are very bad, it is difficult to reach, far from civilization, and no archaeological finds have been made. Recent archaeological investigations confirmed the assumption that the Brocken was not a sacrificial mountain from pre-Christian times.

The name of the venerated deity differs in the individual works, however. In the descriptions, particular emphasis is placed on female participants in the Witches' Sabbath. Sometimes the Walpurgis celebration was also associated with Easter, so that the origin of the Easter fire was seen in the May festival .

Faith

Since the Middle Ages , the population has believed that magic women gather on the Brocken at night. The origin of this belief has been assumed among the Saxons since the 19th century , which cannot be proven historically.

The majority of the population who lived in the immediate vicinity of the Brocken did not believe in witches' meetings on the mountain. Especially in the 17th century, belief in magical beings decreased. Count Heinrich zu Stolberg (1551–1615) had the accusers arrested in a trial in 1611 in which a woman was accused of witchcraft.

In his Quaestio Nona in 1659, the lawyer and diplomat Justus Oldekop, in his pamphlet (463 p.) Against Benedict Carpzov, particularly addresses the meeting of the devil and the "corporalem exportationem Veneficorum et sagarum (poisoners and witches) in montem Bructerorum, uffm Blocksberge" and presents these things - as in earlier writings - as empty fantasy and clumsy superstitions, which must lead him from one “nullity” to another.

Geographical names

Some rock formations on the Brocken have names relating to witches and the Walpurgis Night. In the first half of the 18th century, the names "witch altar" and " devil's pulpit " were created. In all likelihood, they were introduced by the Brocken guides, who usually accompanied visitors to the Brocken and wanted to create new attractions. Since the end of the same century, the names can also be found in the travel literature of the Harz. So the rocks became part of many Brocken visits.

A travel guide from 1823 traced the origin of the names back to a well-known fable. According to this, the devil holds a big festival on the Brocken, at which he preaches to the guests from the devil's pulpit. He has the dishes prepared for them on the witch's altar. The Walpurgis Night Celebration is presented similarly in other travel books.

In the first half of the 18th century there were already other names for various rock formations. Brocken landlord Eduard Nehse (management of the Brockenhaus: 1834–1850) brought out a Brockenkarte in 1849, on which the “ Hexentanzplatz ”, the “Hexenmoor”, the “Hexenteich” and the “Hexenbrunnen” are also marked. He also made up the story that the witch's washbasin keeps filling up with water by itself.

Other names in the Harz include the “Hexenbank” near Hahnenklee , the “Hexen Mother” and the “Hexentreppe” near Thale , the Hexenritt descent in Braunlage and the “Hexenküche” in Okertal . Names that refer to the devil include the " Devil's Baths " and the " Devil's Hole " near Osterode , the "Devil's Bridge" that leads over the Bode , the "Devil's Hole" and "Devil's Wall" near Blankenburg , the "Devil's Mills" on the Ramberg and "Teufelstal" in the Okertal. Since 2003 you can cross the Harz via the Harz Hexenstieg .

Walpurgis night celebrations

Every year around 100,000 people celebrate the Walpurgis Festival in and around the Harz Mountains; some estimates put it at 150,000. Little is known about the history of the festival. The celebrations for Walpurgis Night have only been mentioned in regional literature since the 1920s. The general literature deals with the subject only since the end of the 20th century.

history

The forerunners of these celebrations are, on the one hand, recitations by some visitors to the Brocken from Goethe's Walpurgis night scene from Faust. A tragedy . On the other hand, the first Brocken landlord Johann Friedrich Christian Gerlach (1763–1834; hotel management: 1801–1834) initiated musical performances on the Brocken, to which people danced with broomsticks or similar things. Which are already reported Hans Christian Andersen , who had participated in such an event in 1831st For both, however, there was no fixed time and was preferably carried out in warmer seasons, as it is very cold on the Brocken on May 1st, so that hardly any visitors came to the Brocken.

The first Walpurgis Night celebration on the Brocken was organized in 1896 by Rudolf Stolle , a publishing bookseller from Bad Harzburg and a member of the Harz Club branch association Bad Harzburg. The festival consisted of a celebration in the Brocken Hotel and a procession to the Teufelskanzel at midnight with a speech. Only male guests were present. For a few years later, Geibel's Mailied was sung in company . From 1901 special trains of the Brocken Railway ran up the Brocken. In 1902 almost 150 guests met for the Walpurgis celebration.

In 1903 the celebration took place for the first time on a larger scale on the initiative of the Walpurgis Society of Bad Harzburg, so that the year later is considered the date of foundation. For the first time, a large number of women were among the 500 attendees.

Prince Christian Ernst zu Stollberg-Wernigerode, to whom the Brocken belonged at that time, banned celebrations in a similar manner from 1905 as in the previous year. The Walpurgis Night Celebration took place again to a lesser extent until 1907. At this time, festive events for Walpurgis Night also developed in the surrounding hotels.

In 1908 the Walpurgis Festival on the Brocken was organized by the Wernigerode Municipal Transport Office, founded on April 27, 1908, together with Rudolf Schade , who had been Brocken landlord since April 1, 1908. This and celebrations in the following years were associated with much more customs than the previous festivals. For example, the Brocken Railway was festively decorated and sweets were thrown from the train. This was holding Schierker pastor Dietrich Vorwerk the speech, which was a model for the following year. The last public Walpurgis celebration for the time being took place in 1939.

In the First World War, no official celebrations were held on Walpurgis Night. In 1932, which was also the 100th year of Goethe's death, the “30th Walpurgis celebration on the Brocken ”. The event was broadcast on Fox Tönender Wochenschau . At the time of National Socialism , besides “May has come”, the Germany song was also sung. In 1934, parallel to the Walpurgis Festival, the Hitler Youth met at the beginning of National Labor Day. Because of this, the “Devil's” address could not be given outdoors. From 1936, the Walpurgis Night celebration was moved to the Saturday of the first week of May to enable participation in the celebrations of the Hitler Youth on May 1st.

After the Second World War , the Brocken belonged to the Soviet occupation zone . There were no celebrations in the style of previous years in the GDR ; the Brocken was a restricted area from 1961 . Instead, there were parades and speeches on Walpurgis Evening , the international struggle and holiday of the working people for peace and socialism .

In West Germany , Walpurgis celebrations were organized in more and more places in the western Harz region. After the reunification , the custom of this festival quickly spread throughout the Harz. Since then, there have been no public Walpurgis celebrations on the Brocken for environmental reasons. Since 1997, smaller events have been organized on the mountain again; in 1998 the Brockenbahn rode again for the first time to celebrate on the summit.

criticism

The focus of the festival is on happiness and entertainment. Unpleasant aspects of the past, such as the witch trials, would be left out, so that only the beautiful customs would be revived. The trivializing way of dealing with the subject of witch hunt is criticized.

After the Second World War, the ritual of burning witch dolls became widespread. This should symbolically represent the victory of good over evil and spring over winter. However, this custom has been criticized since the 1960s. The problem with the burning of witches was the revival of the horrific time of the Inquisition and the witch trials for the fun of those present. So the burns were gradually abolished. Instead, other legends such as the Wild Hunter, the Gittelder Hexe or the King Huebich were performed in a playful way.

souvenir

The exact time since witch souvenirs have been produced and sold in the Harz is not known. The objects manufactured by Brocken landlord Rudolf Schade (1868–1927; hotel management: 1908–1927) are seen as their forerunners . He was already making pins for the Walpurgis celebration in 1910. He also carried the stamp “Official postcard. Brocken “. Later there were also so-called Brocken vouchers and Brockengeld, including with witch motifs. The great popularity of the witch souvenirs probably only arose after the Second World War .

Witch representations and dolls

The witches depicted ride a broom; the Brocken is often shown in the background. Sometimes the Harz motto "Let the fir tree green, the ore grow, God give us all a happy heart" is also printed. The proverb was originally a miner's saying from the Ore Mountains .

The witches are very different in their appearance. There are both old and young; these range from ugly to beautiful. The clothing is often patched. Some also wear glasses and slippers, traditionally mostly a headscarf, more recently a pointed hat.

Today the witch is an advertising symbol of the Harz and the best-selling souvenir in the Harz. It is presented on many souvenir items and has other symbol of the Harz displaced, such as the Wilden Mann , which is about to of the logo resin Association for History and Archeology is, or the Green pine still a symbol of today resin clubs is.

Postcards

| year | Copies sold |

|---|---|

| 1878 | 6491 |

| 1895 | 137.046 |

| 1896 | 134.046 |

| 1903 | 265.185 |

| 1906 | 314,325 |

The spread of the Brocken witches on postcards began with the advent of the postcard as a means of communication. However, the first copies appeared as early as the 1880s. The early maps referred exclusively to the Brocken and the Walpurgis celebration on Walpurgis Night on the mountain. This changed over time, so that the representations of the witches vary greatly; the Brockenhotel is also often shown.

literature

- Ines Köhler-Zülch : Witch phenomena and tourism. Souvenir - legend - custom. In: Leander Petzoldt , Siegfried de Rachewiltz, Petra Streng (eds.): The image of the world in the folk tale (= contributions to European ethnology and folklore. Series B: Conference reports and materials. Vol. 4). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1993, ISBN 3-631-44136-3 , pp. 275-319.

- Ines Köhler-Zülch: Witches and Walpurgis Night in the Harz Mountains. Realized imaginations. In: Gudrun Schwibbe, Regina Bendix (Hrsg.): Night - ways into other worlds. Schmerse, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-926920-35-1 , pp. 157-174.

- Thomas P. Becker: Myth Walpurgis Night, notes from a historical perspective . In: ezw-materialdienst 4/07

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Eduard Jacobs : The Brocken in History and Sage (= Historical Commission of the Province of Saxony. New Year's Papers . Bd. 3, ZDB -ID 1433506-2 ). Pfeffer, Halle 1879.

- ↑ Johannes Praetorius: Blockes-Berg's performance or detailed geographical report of the high, excellent old and famous Blockes-Mountains: same from the witch's ride and magic sabbath, so on such mountains the monsters from all over Germany. To put on Walpurgis nights; Composed from many Autoribus and adorned with beautiful rarities sampt associated figures; Besides an appendice from the Blockes-Berge as well as the Alten Reinstein and Baumans Höle am Hartz. Disk, Leipzig; Arnst, Frankfurt am Main 1668. ( Digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- ↑ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust. - A tragedy. Cotta'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Tübingen, 1808 ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- ↑ Blocksberg, blocker Mountain, Mountain Blox, Brock Mountain, Mountain Brocker. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 4, Leipzig 1733, column 176 f (here column 177 with reference to Praetorius).

- ↑ Thomas P. Becker: Myth Walpurgis Night. 2007 ( full text ( memento of August 24, 2004 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Joachim Lehrmann : For and against the madness - witch hunt in the Hochstift Hildesheim '', and "A contender against the witch madness" - Lower Saxony's unknown early enlightener (Justus Oldekop). Lehrte 2003, 272 pp., ISBN 978-3-9803642-3-2 , pp. 194-242.

- ↑ a b Gerhard Eckert : The Brocken, mountain in the middle of Germany. yesterday and today. 3rd, revised edition. Husum Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft, Husum 1994, ISBN 3-88042-485-3 .

- ↑ a b c d e Georg von Gynz-Rekowski, Hermann D. Oemler : Brocken. History, home, humor. Gerig Verlag, Königstein / Taunus 1991, ISBN 3-928275-05-4 .

- ↑ Thorsten Schmidt, Jürgen Korsch: The Brocken. Mountain between nature and technology. 2nd, heavily revised edition. Schmidt-Buch-Verlag, Wernigerode 1998, ISBN 3-928977-59-8 .