Jonah

|

Book of the Twelve Prophets of the Tanakh Old Testament Minor Prophets |

|---|

| Names after the ÖVBE |

Jonah (also Jonas ; Hebrew יוֹנָה Jônâ ; Greek Ἰωνᾶς Iōnâs ; Latin Jonas ; Arabic يُونُس, DMG Yūnus ) is the name of the prophet of a book in the Tanach that tells of him. It belongs to the Book of the Twelve Prophets and forms a special literary genre, because it is not a collection of prophetic words, but a biblical story about a prophet, his mission to Nineveh and his instruction by YHWH , the God of Israel. Close parallels to this are the stories about Elijah and Elisha in the 1st Book of Kings .

Emergence

Linguistic, religious and motivational observations clearly indicate a much later origin than stated in the narrative itself, so that the overwhelming majority of exegetes dated the book to the Persian or Hellenistic period , i.e. the 5th - 3rd centuries. Century BC BC, date. Earlier dates are only rarely represented, mostly based on the historical date of 612 BC. BC documented the destruction of the city of Nineveh, which cannot be found in the text. A clear line is drawn towards the bottom: On the basis of Sir 49.10 EU , where the "Twelve Prophets" are mentioned as a collection, the Book of Jonah is dated to the time after approx. 190 BC. No longer possible.

Continuous efforts were made to divide the book of Jonah in several literary layers, since the name of God YHWH and the like lohim be used side by side. Since the 19th century, attempts have been made to derive a multilayered structure in the Book of Jonah , analogous to the separation of sources in the Pentateuch . Given the recognizable literary uniformity of the book, all these attempts can now be regarded as having failed.

Text and structure

structure

The book of Jonah is divided into two parts. The first describes the flight of the prophet from his mission, the second the - at least outwardly - fulfillment of this mission. Each of these parts is divided into three scenes, of which the second and third each comprise three stages of action.

- Cape. 1–2 Part One: At Sea - The Outward Escape

- 1.1–3 EU : God's first commission, Jonas Flucht

- 1,4–16: On the sea in the ship - the sailors' fear of God and Jonas resistance

- 2.1–11: In the sea, in the belly of the whale

- Cape. 3–4 Part Two: The City of Nineveh - The Inner Escape

- 3.1–3 EU : God's second commission, Jonas Aufbruch

- 3, 4–10: In Nineveh - repentance of sinners and Jonas resistance

- 4.1–11: In and near Nineveh - The teaching of the prophet

Both parts begin with the word event formula : "And the word of YHWH went to Jonah ..." Both times Jonah turns to go - first of all towards the west, only the second time he goes to Nineveh. Parallels can also be found in the place of the action (sea - Nineveh and surroundings) and in the characters (seafarers and captains - city dwellers and king). Each of the two scenes following the word event formula has three episodes. The first describes a God-sent (real or perceived) emergency; the second a prayer and accompanying acts; the third an answer from God.

Table of contents

- 1st chapter

The story begins with Jonah receiving an order from God to go to Nineveh and threaten the city and its inhabitants with a judgment of God because of their wickedness . Jonah is on his way, but not east to Nineveh (today's Iraq ), but to Jaffa (Jafo) , where he gets on a ship to Tarsis ( Tarshish , presumably Tartessus in today's Spain); So seen from Israel he is fleeing in the opposite direction. God kindles a huge storm that puts the ship in distress. Lot unmasked Jonah as the person responsible, who confesses his guilt and proposes to be thrown into the sea. After the seamen tried unsuccessfully to get ashore by rowing, they throw Jonah into the sea. Since the storm stops instantly, the seafarers are converted to YHWH.

- 2nd chapter

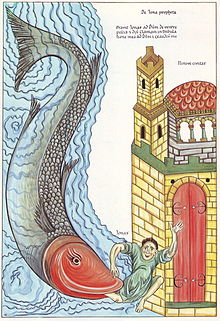

Jonah is devoured by a large fish. He prays in its belly and is spat out on land after three days and three nights.

- 3rd chapter

Jonah now receives the same assignment as at the beginning; this time he actually goes to Nineveh to announce that there are only forty days left until the city is destroyed. This announcement triggers a penance movement among the Ninevites, which includes the entire population, including animals. The repentance means that God pardoned the town, so the announced court is not enforced.

- 4th chapter

In Jonah, this pardon for the city causes great anger. He set out to flee to Tarshish because he knew that God is a gracious and merciful God who will ultimately not carry out judgment on the city. Now, after the pardon of Nineveh, he wishes for death.

Apparently in a flashback it is told how Jonah left the city after the Annunciation in Nineveh and built a tabernacle outside to await what was to come. God made a castor tree grow over this hut , providing shade and joy for Jonah. But the next morning God let the castor wither. In addition, he let a hot east wind rise, which made Jonah swoon and the desire to die. Looking at this "castor oil episode", God now asks the prophet, angry about the pardon of Nineveh:

“You lament the bush, which you did not care for, nor did you raise it, which was made in one night and perished in one night; and I shouldn't complain. Nineveh, such a big city, with more than 120,000 people who don't know what is right and left, and also many animals? "

This ends the narrative without any answer or other reaction to Jonas being reported to this question.

theology

Historical background

The main character probably refers to that Jona Ben Amittai , who after 2. Kings 14.25 EU had predicted the restoration of the old Israelite northern border by King Jeroboam II (781-742 BC). In the biblical calendar, the time of Jonah is to be set before or during the reign of Jeroboam II, who became king of Israel in the fifteenth year of his brother Amaziah's reign (800–783 BC). Both father was King Jehoash (around 840-801 v. Chr.). His home was therefore the place Gat-Hefer in Galilee . So far there are no extra-biblical written evidence for the historicity of Jonah. Apparently his grave is in the village of Nebi-Junis.

The Assyrian city of Nineveh was founded in 612 BC. And became synonymous with a godless or godforsaken city for Jews and Christianity.

However, neither the characters nor the scenes shown show any historical-individual profile. “The name, nationality and god of the 'King of Nineveh' are not mentioned, so that the narrative is accordingly not anchored in a specific time. Both the political dimension and religious details are missing. "

Literary peculiarities

The final rhetorical question in 4.10–11 EU suggests that the Book of Jonah is a religious teacher narration. This generic definition is almost universally accepted in research today. Had the narrator been primarily concerned with reporting past events, such as a dramatic experience from the life of the prophet Jonah, he would certainly have chosen a rounded conclusion and clarified how Jonah reacts to God's question.

The fact that the Book of Jonah does not provide a historical account is evident from a number of historical inconsistencies - apart from the open ending.

This includes first of all the entanglement of Jonas by the big fish, which was ridiculed by critics of the early church in antiquity and whose historicity should be secured in modern research by sometimes very strange explanations. Some eighteenth-century researchers suspected that Jona had been picked up by a ship called the “Big Fish” or that he had stayed in a hostel called “Zum Walfisch”. The explanation of the intertwining as a dream experience, already advocated in the 18th century, is less bizarre, but it has no basis in the text either. Attempts to make Jonas' entanglement historically probable by referring to parallel cases have also not convinced the majority of research. In the Anglo-Saxon world, the case of a certain James Bartley, an American whale hunter, was discussed at the beginning of the 20th century, who was devoured by a sperm whale off the Falkland Islands in 1891 , but was rescued alive by his comrades from the stomach of the hunted whale. Bartley is said to have been unconscious when he was rescued and attacked by the gastric juice of the whale. This has little to do with the depiction of the Book of Jonah (Chapter 2), according to which Jonah prays a psalm in the stomach of the big fish and is apparently spit on land unharmed. The devouring episode can be understood more appropriately if one takes from it instead a pictorial statement about God (cf. below the paragraph “On the devouring episode”).

Another unhistorical feature is the portrayal of Nineveh. Nineveh is considered the residence of a king in the Book of Jonah (chap. 3), but in fact the city was only the central Assyrian residence since Sennacherib , which was also perceived as such in Israel, i.e. after 705 BC. And thus long after the historical Jonah. Apart from that, in the Nineveh depiction of the Book of Jonah, in addition to the Assyrian elements, some can be found that belong to the ancient concept of the Persians . The combination of Assyrian and Persian elements suggests that there is no historically accurate representation of Nineveh, but a picture of Nineveh that comes from a time in which both the Assyrian and Persian empires were already in the past.

The explanation of the book of Jonah as a teacher narration - and not as a representation of history - is not only predominant in the field of historical-critical biblical studies . Even in evangelical circles, which are usually hostile to historical-critical biblical research, there is a certain openness to this basic understanding of the Jonah story.

Interpretative approaches

The open final question encourages readers to understand the justification of God's compassion for Nineveh. So far the concern of the text is clearly understandable. The real problem has not yet been grasped, however, as it is not yet clear what difficulty this pardon might entail. In relation to the character level of the narrative, this means: The interpretation has to clarify why Jonah first tries to evade the mission to Nineveh and why he is angry to death after Nineveh has been pardoned.

Various interpretive approaches have been proposed to explain Jonah's extreme reactions:

a) Jonah does not want the pardon of Nineveh because he does not grant non-Israelite peoples the gracious attention of God . The Ninevites stand as a symbol for the non-Israelite peoples ("heathens") in general, the Jonah figure is understood as a representative of an Israelite exclusivism that wants to see God's grace restricted to the people of Israel chosen by God. Of course, Jonah has to learn from the castor oil that this restriction does not apply. God is not only there for Israel, he cares for all peoples. With this approach, the Jonah narrative can be viewed as a satire , with the Jonage figure as a narrow-minded joke at its center. Their experiences reveal the impossibility of a narrow-minded religious attitude.

b) A second interpretation is based on the assumption that Jonah does not want to appear as a false prophet , because he suspects from the beginning that the judgment he is supposed to announce will not come. After the judgment did not arrive, which God ultimately forced him to announce, he sees himself disavowed by God and therefore wants to die.

c) A third approach suggests that Jonah does not want the pardon of Nineveh because he is jealous for God's righteousness and is therefore repugnant to his grace .

d) If one takes more into account than in the interpretation approaches b) and c) that Jonah is sent to a distant metropolis (the problem of true and false prophecy as well as that of God's justice and grace could also - less noticeable in the Old Testament environment - in a Mission to an Israelite king), and if at the same time, in contrast to the interpretation approach a), Nineveh is not understood as pars pro toto for the non-Israelites at all, but according to the other Old Testament findings initially as the capital of Assyria, i.e. a world power that is one for Israel was a dangerous opponent and who ultimately brought Israel under their hegemony, then a fourth interpretation approach offers itself: Jonah tries to evade the mission to Nineveh, because he does not want to contribute by issuing a court warning to the dangerous Nineveh repenting. He knows that in this case the gracious God will pardon Israel's enemies and that such a possible threat to Israel continues . This interpretation is based on the assumption that the Book of Jonah deals with a deep disappointment that must have existed in Israel after it was under the domination of foreign great powers for centuries. This was the case after the Babylonian exile , when Israel came under Persian and then Hellenistic supremacy. The book of Jonah reflects the changing predominance of foreign great powers insofar as not only Assyrian, but also Persian elements are present in its depiction of Nineveh. The Nineveh of the Book of Jonah stands as a symbol for all the great powers that ruled over Israel. For pious Israelites, in view of the continued predominance of foreign powers, the question had to be asked why God does not end this predominance over the chosen people. The scope of this conflict becomes clear when one considers that Israel had experienced through the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem and the exile of large parts of the population how existence-threatening the domination of foreign great powers can be.

All four interpretive approaches have been represented in different variations and are worth considering. In addition, there are exegetical statements according to which the Book of Jonah is deliberately kept ambiguous, so that the commitment to a certain interpretation approach does not do justice to the full meaning of the text.

In all four approaches, the solution to the conflict must result from concerns about the final question ( Jonah 4, 10–11 EU ).

For interpretation approach a) it follows from the final question that God is the creator of the whole world, who cares for all his creatures, including the non-Israelites, for whom the people of Nineveh stand, and also for their animals. A limitation of God's gracious care to Israel is not possible due to his all-embracing creator.

For interpretation approach b) it can be inferred from the final question that God as the Creator has compassion for all his creatures, so that he does not insist on the fulfillment of a prophecy - even if, as in Jonas' case, he himself shared the prophet with the Proclaiming this prophecy.

The fact that God has compassion for all of his creatures is also important for interpretation approach c); Because of this compassion, the pardon of guilty people is more important to God than the basic implementation of his justice.

With interpretation approach d), as with interpretation approach a), it is important that the final question justifies the pardon of Nineveh with the fact that God is the creator of all living beings; thus the great powers that rule over Israel are also designated as its creatures. However, this does not yet provide a solution to the problem. The fundamental question of why God does not end the supremacy of foreign great powers over his chosen people requires information about what, despite this supremacy, Israel's continuing prerogative consists of. A hint to this can probably be found in the conspicuous remark that the people of Nineveh do not know where right and left is ( Jonah 4:11 EU ). By denying Nineveh this knowledge, it should be indirectly reminded that Israel has a knowledge of right and left. From other Old Testament passages this statement can be recognized as an allusion to the fact that Israel knows the law revealed by God, the Torah . From this it follows that Israel will continue to exist as God's chosen people even under the domination of foreign great powers, whose symbol is Nineveh, if it adheres to the law that God gave it through Moses.

To the devouring episode

The most powerful episode of the narrative is the devouring and spitting of the big fish in chapter 2. Viewing the episode in isolation has been of great importance to Christendom, who saw in the devouring and salvation Jonas a symbol of the death and resurrection of Jesus. This aspect of the history of the impact begins with the word of Jesus handed down in Matthew 12.40 EU

"For as Jonah was in the belly of the fish for three days and three nights, so the Son of Man will be in the womb of the earth for three days and three nights."

Jonah is represented as a resurrection symbol on many ancient Christian sarcophagi, as well as on baptismal fonts.

In research on the Jonabuch, the devouring scene attracted particular interest. In the paragraph on the literary genre (cf. above) it was already mentioned that modern research on the book endeavored from the beginning to prove its historicity, which for its part had already been contested in antiquity. After this project had proven to be fruitless and research increasingly began to understand the Book of Jonah in terms of literature and tradition (as the result of certain legends or narrative traditions), many parallels from myths, legends and stories from around the world were collected, and the Against this background, the devouring episode was seen as the processing of a widespread solar myth. Depth psychological interpretations were also undertaken. The fact that the devouring episode plays such an important role in the perception of the Jonah tale, although it is more of a transit scene in the book itself, is undoubtedly due to the fact that it can be combined with basic human experiences of the end and new beginning.

Looking at the history of the entanglement episode, it hardly makes sense to think of the processing of an original solar myth; on the contrary, it seems plausible that it was influenced by Indian substances that came to the eastern Mediterranean after Alexander the Great made his move to India. In the context of the Book of Jonah, the devouring episode expresses the power of God as the Creator of heaven and earth (cf. Jonas Confession in Jonah 1,9 EU ): By describing that God saves Jonah through the big fish, it leaves the fleeting prophet Experience God's power in the depths of the sea - at the same time, the story of Jonah lets us experience the overwhelming power he sought to oppose.

Impact history

The protagonist of the Book of Jonah has been recognized as a prophet in Judaism since the formation of the canon , and his figure also plays a role in many Jewish legends.

Christianity

In the Christian churches, Jonah (sws) is venerated as a saint or viewed as a memorable witness of faith. The Book of Jonah is one of the most popular biblical stories in Christianity .

The Christian memorial days are:

- Evangelical: September 22 on the calendar of the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod

- Roman Catholic: September 21

- Orthodox: September 21 and September 22

- Armenian: September 22

- Coptic: September 22nd

Islam

In Islam , Yūnus , his Arabic name, is regarded as the prophet and forerunner of Muhammad ; the Sura 10 is named after him. The prominent importance of the devouring episode in the perception of the Jonah story is also shown in the fact that Jonah is called "the man of the fish" ( Sura 21 , 87) or "the one with the fish" ( Sura 68 , 48) in the Koran . Many Islamic legends have grown up around him.

Bahaitum

Like the miracles of Jesus , the Jonah story is also interpreted allegorically in the Baha'i religion : the fish stands for the environment of the prophet Jonah and the hostility of the people. To be saved from the fish's belly is to carry out his teachings and lead people to faith. Likewise, in the Baha'i religion the miracles of the central figures of the religions are interpreted allegorically.

Modern culture

In addition, the Jonabuch has given literature, the visual arts and the entertainment industry numerous suggestions, for example for Herman Melville's novel Moby Dick .

literature

Exegetical literature

- research paper

- Claude Lichtert: Un siècle de recherche à propos de Jonas. Revue Biblique 112 (2005), 192-214; 330-354.

- For introduction and further literature indexing

- Erhard Blum : The Book of Jonah. In: HV Geppert (Hrsg.): Große Werke der Literatur II. Augsburg 1992, pp. 9–21.

- Meik Gerhards : Studies on the Jonabuch. Biblical-theological studies 78, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2006, ISBN 3-7887-2181-2 .

- Rainer Kessler : Jona. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 3, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-035-2 , Sp. 629-632.

- Hans Walter Wolff : Studies for the Jonabuch. With an appendix by Jörg Jeremias : The Jonabuch in research since HW Wolff. Third expanded edition of Wolff's monograph, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2003, ISBN 3-7887-1865-X .

- Comments (since 1990)

- Friedemann W. Golka : Jona. Stuttgart 1991 = 2nd edition Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-7668-3949-7 .

- Jörg Jeremias : The prophets Joel, Obadja, Jona, Micha. ATD 24/3, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-51242-5 , pp. 75-112.

- Jack M. Sasson: Jonah. Anchor Bible, New York a. a. 1990.

- Other exegetical literature

- Jean-Gérard Bursztein : Ancient Hebrew Healing Experience and Psychoanalysis. The book of Jonah. Vienna: Turia + Kant 2009. ISBN 978-3-85132-552-2

- Hartmut Gese : Jona ben Amittai and the book of Jonah. In: ders .: Old Testament Studies. Tübingen 1991, 122-138. (Rejection of the interpretation as satire or a narrow-minded interpretation of the Jonah figure)

- Klaus Koenen : Biblical-theological considerations on the Jonabuch. In: New Testament Journal. 6: 31-39 (2000). (clear rejection of a decision for a single interpretation approach)

- WS La Sor / DA Hubbard / FW Bush: The Old Testament. Origin, history, message. Edited by H. Egelkrauth, Gießen (et al.) 1989. ISBN 3-7655-9344-3 (This is an evangelical "introduction" to the Old Testament, which in the chapter on the Book of Jonah [pp. 409-418] compared to the basic understanding as a teacher narration - and not as a history report - is open)

- Rüdiger Lux : Jonah. Prophet between “denial” and “obedience”. FRLANT 162. Göttingen 1994.

- Beat Weber : Jonah. The stubborn prophet and the gracious God (BG 27), Evangelische Verlagsanstalt , Leipzig 2012. ISBN 978-3-374-03050-7

- To the devouring episode

- Meik Gerhards: On the motif-historical background of the entanglement of Jona. In: Theologische Zeitschrift (Basel) 59 (2003), 222–247.

- Hans Schmidt: Jonah. A study of the comparative history of religion, research on religion and literature in the Old and New Testament. 9, Göttingen 1907. (assuming evolutionist thinking that is outdated in today's narrative research, assumes that the entanglement motif of the Jona book is a variant of an ancient, widespread solar myth; the book is still important today as a collection of material for parallels to the entanglement episode)

- AJ Wilson: The Sign of Jonah and its modern Confirmation. In: Princeton Theological Review. 35: 630-642 (1927). (Attempt to underpin the historicity of the entanglement with reference to parallel cases, including J. Bartley)

- To the history of the impact

- Uwe Steffen : The mystery of death and resurrection. Forms and changes of the Jonah motif. Göttingen 1963. (Material-rich collection on the history of motifs and effects of the entanglement motif with depth psychological interpretation)

- Uwe Steffen: The Jona story. Their interpretation and representation in Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Neukirchen-Vluyn 1994, ISBN 3-7887-1492-1 .

Comparative literature science

- Simone Frieling: The rebellious prophet. Jonah in modern literature. Vandenhoeck Collection , Göttingen 1999. ISBN 3-525-01225-X (Collection of texts and text excerpts as well as two essays: Jona and the poets by Dieter Lamping and Jona - a never-ending story by Rüdiger Lux )

Fiction

- As a quote within a work

- Herman Melville : Moby Dick . Chapter 9: The Sermon (by Father Mapple)

- As a motif within a work

- Carlo Collodi : Pinocchio . Chapter 35: Pinocchio discovered in the body of the shark ... Whom? (As in the Jonah book, the devouring fish, here as a "basking shark", represents the final purification of the protagonist.)

- As an independent variation of the Jonah book

- Ulrich Karger : Kindskopf - A visitation . Novella . EA Berlin 2002. New TB edition. Edition Gegenwind , Norderstedt 2012; ISBN 978-3-8448-1262-6 (Tied closely to the sequence and dynamics of the Jona book, the protagonist tries to escape his wife's desire for children.)

See also

Web links

- bibleserver.com Text of the Book of Jonah (you can choose between different translations)

- The Book of Jonah - Against God . Commentary and interpretation including the text of the revised standard translation - published within the Bible project of the Archdiocese of Cologne "In Principio"

- zum.de Collection of materials for religious educators

- Meik Gerhards: Jonah / Jonabuch. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- The Jonabuch bibelwissenschaft.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Jörg Jeremias : The prophets Joel, Obadja, Jona, Micha. ATD 24/3, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-51242-5 , p. 80

- ↑ See Erich Zenger et al. a .: Introduction to the Old Testament. 5th edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-17-018332-X , p. 550

- ↑ See Erich Zenger et al. a .: Introduction to the Old Testament. 5th edition. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-17-018332-X , p. 549 f.

- ↑ Cf. U. Simon: Jona. A Jewish comment. In: Stuttgarter Biblische Studien 157 (1994) 50.

- ↑ a b Thomas Söding : Jona and others: The "small prophets". (PDF; 127 kB) (No longer available online.) 2005, p. 13 , archived from the original on February 4, 2018 ; accessed on April 30, 2017 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Wilhelm Litten: Persian honeymoon. Georg Stilke, Berlin 1925, p. 161

- ↑ a b c d e Meik Gerhards: Jona / Jonabuch. In: The Bible Lexicon. German Bible Society , April 2008, accessed on April 30, 2017 (Section 6.).

- ↑ U. Simon: Jonah. A Jewish comment. In: Stuttgarter Biblische Studien 157 (1994) 31. Quoted from Erich Zenger u. a .: Introduction to the Old Testament , p. 548

- ↑ Cf. Jörg Jeremias: The prophets Joel, Obadja, Jona, Micha. ATD 24/3, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-51242-5 , p. 92f.

- ↑ See: Edward B. Davis: A Whale of a Tale: Fundamentalist Fish Stories. In: Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, 43. 1991, pp. 224–237 , accessed on May 8, 2017 (English).

- ↑ Jörg Jeremias: The prophets Joel, Obadja, Jona, Micha. ATD 24/3, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-51242-5 , p. 99

- ↑ a b Jörg Jeremias: The prophets Joel, Obadja, Jona, Micha. ATD 24/3, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-51242-5 , p. 110

- ↑ Jörg Jeremias: The prophets Joel, Obadja, Jona, Micha. ATD 24/3, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-51242-5 , p. 78

- ↑ Cf. Jörg Jeremias: The prophets Joel, Obadja, Jona, Micha. ATD 24/3, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-51242-5 , p. 79

- ↑ See Hans-Peter Mathys: Dichter und Beter. Theologians from the late Old Testament period. Saint-Paul, Freiburg i. Üe. 1994, ISBN 3-525-53767-0 , p. 219, note 4

- ↑ Cf. Jörg Jeremias: The repentance of God. Aspects of the Old Testament conception of God (= BThSt 31). 2nd edition Neukirchen-Vluyn 1997, p. 103