Canadian National Vimy Memorial

| Canadian National Vimy Memorial Mémorial national du Canada à Vimy |

|

|---|---|

|

Historic Place of Canada Lieu patrimonial du Canada |

|

| Recognized since | 1997 |

| Type | National Historic Site |

| place | Vimy , France |

| Coordinates | 50 ° 22 '46 " N , 2 ° 46' 25" E |

| Recognized by | Canadian Federal Government |

| Approved by | Historic Sites and Monuments Act |

| Entry Canadian List of Monuments | |

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial is a memorial in France dedicated to the Canadian Expeditionary Force who died in World War I. It also serves as an honorable memorial for the Canadian soldiers of World War I who were killed or missing and who have no burial site. The monument is located in a 100 hectare, comparatively well-preserved part of the battlefield over which the Canadians carried out their attack during the " Battle of Vimy Ridge " as part of the Battle of Arras .

The Battle of Vimy Ridge marked the first occasion that all four divisions of the Canadian Canadian Expeditionary Force participated in battle as a single unit. This effort became a national Canadian symbol of a self-sacrificing national feat. France ceded the area on Vimy Hill to Canada indefinitely on condition that Canada erect an open air museum of the battlefield and a memorial. Wartime tunnels, trenches, explosion craters and unexploded ammunition run through the area, which for safety reasons is largely not allowed to be entered. There are several other monuments and cemeteries around the preserved trench lines that are integrated into the open-air museum.

The central monument occupied its artistic creator, the sculptor Walter Seymour Allward (1876 - 1955) for eleven years. The British King Edward VIII unveiled it on July 26, 1936 in the presence of French President Albert Lebrun and over 50,000 guests, including 6,200 visitors from Canada. After many years of renovation, Queen Elizabeth II re- inaugurated the monument on April 9, 2007 at a ceremony commemorating the 90th anniversary of the battle. The facility is maintained by Veterans Affairs Canada, the Canadian Department of War Veterans.

The Vimy Memorial is one of only two entries on the Canadian Monuments List that are outside of Canada. The second is the thematically related Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial for the victims of Newfoundland , which was a Dominion independent of Canada at the time of the First World War .

background

topography

Vimy Ridge (French: Crête de Vimy) is a ridge or a mountain ridge eight kilometers northeast of Arras , which is formed by a gradually rising stratum on the western edge of the Douai plain . The stratification level rises gradually on its west side (step surface) and drops more rapidly on its east side (front side). The strata is nearly seven kilometers long, 700 meters wide at the narrowest point and reaches a height of 145 meters above sea level. M. or 60 meters above the Douai plain, it allows an undisturbed view in all directions.

Conflicts before the Battle of Arras, 1917

The ridge came under German control in October 1914 when the Allied and German troops tried to cross each other in northeastern France during the race to the sea . The French Tenth Army attacked the German positions on the Vimy ridge and the St. Loretto height near Ablain-Saint-Nazaire during the Loretto Battle in May 1915 . During this attack, the French First Moroccan Division briefly managed to take the ridge where the Vimy Memorial stands today, but they could not hold it due to a lack of reinforcements. The French made another attempt during the autumn battle at La Bassée and Arras in September 1915, but again failed to conquer the ridge and suffered heavy losses of approximately 150,000 men.

In February 1916, the British XVII Corps replaced the French Tenth Army in this sector. On May 21, 1916, the German infantry attacked the British lines at a width of 1,800 meters to drive them from positions at the foot of the ridge. The Germans captured several British tunnels and mine craters and dug themselves into the position they had reached. The reason for the attack was the Germans' uncomfortable feeling about the progress of British tunnel construction and countermeasures to German mines. British counterattacks on May 22nd could not change the situation.

The battle for the Vimy ridge

In the Battle of the Vimy Heights, all four Canadian divisions were used together in a closed formation for the first time. The format of the task, however, exceeded the operational capabilities of the Canadian corps and required support from British units, including the British 5th Infantry Division and supplementary artillery and engineer units. The 24th Division of the British I. Corps supported the Canadian Corps on its northern, the XVII. Corps on the southern flank. The Canadians faced the ad hoc group Vimy , based essentially on the I. Bavarian Reserve Corps with three divisions under Karl Ritter von Fasbender .

The attack began on Easter Monday , April 9, 1917 at 5:30 a.m. Light field artillery fired barrages that were brought forward in fixed steps, mostly 90 meters every three minutes, while medium and heavy howitzers aimed permanent barrages against known defensive installations. The First, Second and Third Canadian Divisions quickly reached their first targets, but not the Fourth Canadian Division. The Canadian First, Second and Third Divisions reached their second destination for the day at 7:30 p.m. Since the Fourth Canadian Division had not achieved their first daily goal on the top of the ridge, the further advance was delayed, the Third Division also had to secure its northern flank, which tied up resources. Reserve units of the 4th Canadian Division renewed the attack on the German positions at the top of the ridge and forced the German troops to withdraw from Hill 145. The withdrawal also took place because the defenders ran out of ammunition.

On the morning of April 10, the Canadian Corps Commander Lieutenant-General Julian HG Byng moved in with three fresh brigades to support the attack. The fresh units were able to overcome the positions and captured the third line including hill 135 and the village of Thélus at 11:00. At 2 p.m., the First and Second Canadian Divisions were able to achieve their final goals. At that time only the so-called Pimple , a heavily defended hill west of Givenchy-en-Gohelle , was the only German position on Vimy Ridge. On April 12th, the 10th Canadian Infantry Brigade, with the support of artillery and the 24th British Division, attacked the buried German troops and was able to quickly overcome them. When darkness fell on April 12th, the Canadian Corps had control of the hill. The Canadian Corps suffered 10,602 casualties, 3,598 killed and 7,004 wounded. The German Sixth Army suffered losses of unknown amounts and around 4,000 men were captured.

While not considered Canada's greatest military feat, the battle holds considerable national standing for Canada. The notion that Canada's identity and national consciousness were born in this battle is a widespread belief in Canadian military and general historiography.

history

selection

In 1920 the Canadian government announced that the Imperial War Graves Commission had identified eight sites - five in France and three in Belgium - on which monuments were to be erected (Vimy, Bourlon , Le Quesnel , Dury and Courcelette in France and St. Julien , Hill 62 , and Passendale in Belgium). Each site represented significant Canadian participation, and the Canadian government initially determined that each battlefield should be treated equally and given identical monuments. In September 1920, the Canadian government formed the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission to promote the framework for a competition to design monuments in Europe. The commission met for the first time on November 26, 1920 and decided that the architectural competition should be open to all Canadian architects, designers, sculptors and artists.

The jury consisted of Charles Herbert Reilly from the Royal Institute of British Architects , Paul Philippe Cret from the Société centrale des architectes français and Frank Darling from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada . Each member of the jury was a leader in its field at the time. Interested parties submitted 160 drafts, the jury selected 17 drafts for closer examination and commissioned each finalist to produce a plaster model of their respective draft.

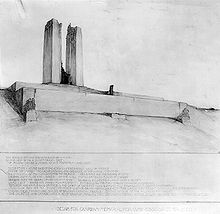

In a report to the commission dated September 10, 1921, the jury recommended that two of the designs should be carried out. In October 1921, the commission formally decided on the design by the sculptor and designer Walter Seymour Allward from Toronto ; the design by Frederick Chapman Clemesha was determined to be runner-up. Due to the complexity of Allward's design, it was not possible to use the design identically on every memorial. The approach of choosing a central memorial contradicted the recommendation of the architectural advisor to the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission Percy Erskine Nobbs, who advocated a number of smaller monuments. The consensus moved in Allwards direction, and its design received widespread support. The commission revised its original plan and decided to build two distinctive monuments - that of Allward and Clemesha - and six smaller identical monuments.

From the outset, the members of the commission discussed where Allwards winning design should be built. The jury was initially of the opinion that Allwards design would be better situated on a hill than on a steep slope like Vimy Ridge.

The committee of the commission recommended that the monument be placed on Hill 62 in Belgium , near the site of the Battle of Mont Sorrel , because the square offered an impressive view. This contradicted the request of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King , who in a speech in May 1922 in the House of Commons of Canada pleaded for a placement on Vimy Ridge. King's position received the unanimous support of Parliament and so the commission chose Vimy Ridge. After the commission made this decision, the government expressed a desire to purchase a larger piece of land along the edge of the property. Between the first and second sessions of Canada's 14th Parliament, Rodolphe Lemieux , Speaker of Canada's House of Commons, went to France to negotiate the purchase of more land. On December 5, 1922, Lemieux entered into an agreement in which France gave Canada "free and forever" the use of 100 acres of land on Vimy Ridge, including Hill 145, in recognition of Canada's war effort. The only condition associated with the donation was that Canada erect a monument on the property to commemorate the Canadian soldiers who fell in World War I and take over the maintenance of the monument and the surrounding park.

construction

According to the competition, Allward spent the remainder of 1921 and the spring of 1922 preparing for his trip to Europe. After selling his house and studio, he finally went to Belgium on June 6, 1922 and spent several months looking for a suitable studio in Belgium and then in Paris.

Allward originally hoped he could use white marble for the facing stone, but Percy Nobbs presented this as a mistake because marble was unsuitable for the climate in northern France. Allward took a two year tour to find a suitable stone with the right color, texture, and brightness. He found the right stone in the ruins of Diocletian's Palace in Split ( Croatia ).

He found there that the palace had not been weathered over the years, which Allward took as evidence of the stone's durability. This "Seget limestone " came from an old Roman quarry near Seget ( Split-Dalmatia County , Croatia ). The difficulties in mining, combined with complicated transport logistics, delayed the delivery of the limestone and thus the construction of the memorial. The first shipment didn't arrive until 1927, and the larger blocks intended for the human figures reached the site in 1931.

At Allward's urging, the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission commissioned Oscar Faber, a Danish structural engineer, in 1924 with the creation of foundation plans and general supervision of the foundation work. Faber had recently designed the substructure for the Menin Gate in Ypres, and he chose a design that used reinforced concrete in place to which the facing brick was to be glued. Major Unwin Simson served as the lead Canadian engineer during construction of the memorial and oversaw much of the day-to-day operations on the site. Allward moved to Paris in 1925 to oversee the construction and carving of the sculptures. Construction began in 1925 and took eleven years to complete. The Imperial War Graves Commission simultaneously employed French and British veterans to carry out the necessary road and off-road work.

While waiting for the first shipment of stone, Samson noticed that the battlefield landscape was starting to deteriorate. Seeing the opportunity not only to keep part of the battlefield but also to keep his staff busy, Samson decided to preserve a short section of the trench line and make the Grange Subway more accessible. Workers built and preserved sections of the sandbag ditch wall, on both the Canadian and German sides of the Grange crater group, by recreating the sacks in concrete. The workforce also built a new concrete entrance for the Grange Subway and installed electrical lighting after excavating part of the tunnel system.

Allward chose a relatively new construction method for the monument: limestone, which is connected to a cast concrete frame. A foundation bed made of 11,000 tons of concrete reinforced with hundreds of tons of steel served as a support bed for the memorial. Sculptors worked the 20 roughly twice as large human figures on site from large blocks of stone. The sculptors used plaster models Allward made in his studio, which are now on display at the Canadian War Museum , and an instrument called a pantograph to reproduce the figures to the correct scale. The sculptors performed their work year-round in temporary studios built around each figure. The inclusion of the names of those killed in France with no known grave was not part of the original draft, and Allward was unhappy when the government asked him to include them. The government acted at the request of the War Graves Committee, which was in charge of the memorial of all killed and missing Commonwealth soldiers and was willing to contribute to the cost of the memorial. Allward argued that including names was not part of the original assignment.

Pilgrimage and unveiling

In 1919, the year after the war ended, around 60,000 British tourists and mourners came to the Western Front. The transatlantic voyage from Canada was time consuming and expensive; many attempts to organize large pilgrimages failed, and the overseas trips were largely carried out individually or in small, unofficial groups. Delegates to the National Congress of the Royal Canadian Legion, a veterans' organization, passed a unanimous resolution in 1928 calling for a pilgrimage to the battlefields of the Western Front. A plan took shape in which the Legion would coordinate the pilgrimage with the unveiling of the Vimy Monument, due to be completed in 1931 or 1932. Due to construction delays at the memorial, the Royal Canadian Legion only announced a pilgrimage to former battlefields in July 1934 in connection with the unveiling of the memorial. Although the exact date for the unveiling of the memorial had not yet been set, the Legion invited veterans to make preliminary reservations at their Ottawa headquarters. The response from veterans and their families was enthusiastic - 1,200 inquiries by November 1934. The Legion announced that the memorial would be unveiled on July 1, 1936, although the government did not yet know when it would be ready.

The Legion and the government established areas for which they were responsible for event planning. The government was responsible for the selection of the official delegation and the program for the official unveiling of the memorial. The Legion was responsible for the more difficult task of organizing the pilgrimage. For the Legion, this included planning food, accommodation and transport for the largest single peace movement of people from Canada to Europe at the time. The Legion took the position that the pilgrimage would be funded by its members without subsidies or financial assistance from Canadian taxpayers, and by early 1935 they had determined that the price of the 3½ week trip, including all meals, accommodation, health insurance, was the price and sea and land transportation, costing Canadian dollars 160 per person ($ 2,814 in 2016 prices). Indirect help came in various forms. The government waived passport fees and provided pilgrims with a special Vimy pass at no additional cost. The state and the private sector also granted their employees paid leave. It was not until April 1936 that the government was ready to publicly commit itself to a date of disclosure, July 26, 1936. On July 16, the five transatlantic liners SS Montrose , SS Montcalm , SS Antonia , SS Ascania and SS Duchess of Bedford with about 6,200 passengers left the port of Montreal , accompanied by the warships HMCS Champlain and HMCS Saguenay and reached on the 24th and 25th July Le Havre .

The limited accommodation options made it necessary for the Legion to house pilgrims in nine cities in northern France and Belgium and to use 235 buses to transport the pilgrims between locations.

On July 26, the day of the ceremony, pilgrims spent the morning and early afternoon exploring the landscape of the memorial park before gathering at the memorial. The HMCS Saguenay sailors provided the honor guard for the ceremony . Also in attendance were the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery Band, French Army engineers, and Franco-Moroccan cavalry who fought on the site during the Loretto Battle . The ceremony itself was broadcast live over shortwave by the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission with support from the British Broadcasting Corporation . Senior Canadian, British and European officials including French President Albert Lebrun and over 50,000 people attended the event. However, Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was absent as he considered it more appropriate for a cabinet veteran to be present as minister.

Before the beginning of the ceremony, King Edward VIII , who was present as King of Canada , was introduced to the guests of honor and he also spent about half an hour with veterans. Two Royal Air Force and two French Air Force squadrons flew over the memorial and bowed their wings in salute. The ceremony itself began with prayers from chaplains representing the Church of England , the United Church of Canada, and the Roman Catholic Church . Ernest Lapointe , Canadian Minister of Justice, spoke first, followed by Edward VIII, who thanked France in both French and English for their generosity and assured those gathered that Canada would never forget its war. Regarding the memorial itself, he said, "It's an inspired expression carved in stone by a skilled Canadian hand, Canada's greeting to its fallen sons."

The King then pulled the Royal Union Flag from the central character Canada Bereft and the military band played The Last Post . The pilgrimage continued and most of the participants visited Ypres before being brought to London by the Royal British Legion . A third of the pilgrims traveled from London to Canada on August 1, while the majority returned to France as government guests for another week before returning home.

Second World War

In 1939 the Canadian government's concern for the general safety of the memorial was heightened by the increasing risk of conflict with Nazi Germany . Canada could do little more than protect the sculptures and the bases of the pylons with sandbags and await developments. When the war broke out in September 1939, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was sent to France and assumed responsibility for the Arras sector, which also included Vimy. In late May 1940, after the British retreat to Dunkirk after the Battle of Arras (1940) , the Germans took control of the memorial and kept the caretaker George Stubbs in an internment camp for Allied civilians in Saint-Denis , France. The alleged destruction of the Vimy Memorial has been widely reported in Canada and the United Kingdom. The rumors prompted the German Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda to formally reject allegations that Germany had damaged or desecrated the monument. To demonstrate that the memorial had not been desecrated, Adolf Hitler , who supposedly admired the memorial for its peaceful nature, was photographed by the press while touring it in person and visiting the preserved trenches on June 2, 1940. The undamaged condition of the memorial was not confirmed until September 1944, when British troops of the 2nd Battalion / Welsh Guards of the Guards Armored Division recaptured Vimy Ridge.

Post-war years

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, very little attention was paid to the Battle of Vimy Ridge or the Vimy Memorial. The Winnipeg Free Press and The Legionary , the magazine of the Royal Canadian Legion , were the only publications to mark the 35th anniversary of the battle in 1952. Only the Halifax Herald mentioned the 40th anniversary in 1957 . Interest in commemoration remained low in the early 1960s, but increased in 1967 with the 50th anniversary of the battle and the hundredth national holiday . A heavily attended ceremony at the memorial in April 1967 was televised live. The commemoration of the battle waned again in the 1970s, not returning until the 125th anniversary of the Canadian Confederation and the 75th anniversary of the battle in 1992. The 1992 ceremony at the memorial was attended by Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and at least 5,000 people. In 1997 and 2002, smaller ceremonies followed at the memorial.

Restoration and rededication

By the end of the century, the many repairs that had been made since the memorial was built had left a patchwork of materials and colors and a disturbing pattern of water leak damage to the joints. In 2005, the Vimy Memorial was closed for major restoration work. Veterans Affairs Canada led the restoration of the memorial in collaboration with other Canadian institutions such as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, as well as various consultants and specialists in military history.

The passage of time, wear and tear, and severe weather conditions resulted in many identified problems, with the most common problem being water damage . When building a monument out of poured concrete that was covered with stone, Allward hadn't considered how these materials would shift against each other over time. The builders and planners failed to leave enough space between the concrete and the stones, which resulted in water penetrating the structure through the walls and platforms and loosening the lime in the concrete foundation and masonry. At the water outlet points, lime was deposited on the outer surfaces and made many of the engraved names illegible. Poor drainage and water drainage from the monument also resulted in significant problems with the platform, terrace and stairs. The restoration project aimed to fix the causes of the damage and included repairs to the stones, walkways, walls, patios, stairs and platforms. In order to respect Allward's original vision of a seamless structure, the restoration team had to remove all foreign materials used in patchwork repairs, replace damaged stones with material from the original quarry in Croatia, and any minor displacements of stones caused by the freeze-thaw Changes were caused to correct. The underlying structural errors have also been corrected.

Queen Elizabeth II , accompanied by Prince Philip , inaugurated the restored monument on April 9, 2007 in a ceremony to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the battle. Other senior Canadian officials including Prime Minister Stephen Harper and French senior officials such as Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin attended the event, as did thousands of Canadian students, veterans of World War II and recent conflicts, and descendants of those who fought in Vimy . It was the largest event at this location since 1936.

Centenary commemoration

The centenary commemoration of the Battle of Vimy Ridge took place on April 9, 2017, which is also the time of the 150th anniversary celebrations of Canada. Pre-event estimates indicated that there would be up to 30,000 spectators in attendance. The Mayor of Arras , Frédéric Leturque, thanked the Canadians as well as the Australians and British, New Zealanders and South Africans for their role in the battles of the First World War in the region.

Canadian dignitaries present included Governor David Johnston , Prince Charles , Prince William, Duke of Cambridge , Prince Harry , and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau . President François Hollande and Prime Minister Bernard Cazeneuve represented France. Elizabeth II made a statement about the governor general.

The Canada Post and France's La Poste have jointly issued a stamp with the designed by each country monument commemorating the centenary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

description

The memorial is located approximately 8 kilometers north of Arras, surrounded by the small towns and cities of Vimy in the east, Givenchy-en-Gohelle in the north, Souchez in the northwest, Neuville-Saint-Vaast in the south and Thélus in the southeast. The place is one of the few places on the former western front where visitors can see the trench lines of a battlefield from the First World War and the associated terrain in a reasonably preserved condition. The total area of the site is 100 hectares, a large part of which is forested and inaccessible to visitors in order to ensure public safety. The rough terrain and hidden duds make cutting grass too dangerous for human workers, so sheep tend the meadows.

The site was established in honor of the Canadian Corps, but it also contains other monuments. These are dedicated to the French Moroccan Division, Lions Club International , and Lt. Col. Mike Watkins. There are also two Commonwealth War Graves Services cemeteries on site: No. 2 Canadian Cemetery and Canadian Cemetery on Givenchy Street. The place is not only a popular place for battlefield tours, but because of its preserved and largely undisturbed condition it is also an important place for the history of the First World War. The Memorial Interpretation Center helps visitors understand the Vimy Memorial, the preserved Battlefield Park, and the history of the Battle of Vimy in the context of Canada's participation in World War I. The Canadian National Vimy Memorial and Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial reportedly comprise nearly 80 percent of the surviving WWI battlefields and receive over a million visitors annually.

Vimy monument

Allward erected the monument on the lookout point of Hill 145, the highest point on the ridge. The memorial contains many stylized elements, including 20 human figures, which help the viewer see the structure as a whole. The front wall, usually confused with the rear, is 7.3 meters high and forms an impenetrable wall of defense. There is a group of figures at each end of the front wall, next to the base of the steps. The Breaking of the Sword is on the south corner of the front wall, while the Sympathy of the Canadians for the Helpless is on the north corner. Common to the two groups are The Defenders and represent the ideals for which Canadians gave their lives during the war. A cannon barrel is carved into a laurel wreath and olive branch above each group to symbolize victory and peace. In Breaking of the Sword there are three young men present, one of whom is sitting and breaking his sword. This statue represents the defeat of militarism and the general desire for peace. This grouping of figures is the most overt image of pacifism in the memorial, with breaking a sword being extremely rare in war memorials. The original plan for the sculpture included a figure crushing a German helmet with his foot. It was later decided to reject this element because of its overtly militaristic images. In Canadians' sympathy for the helpless , a man stands upright while three other figures plagued by hunger or illness crouch and kneel around him. The standing man represents Canada's sympathy for the weak and the oppressed.

The figure of a veiled young woman stands above and in the middle of the front wall and overlooks the Douai plain. Her head bowed, her eyes thrown down, and her chin in one hand. Below her is a sarcophagus wearing a Brodie helmet and sword and wrapped in laurel branches. The sad figure of Canada Bereft , also known as Mother Canada , is a national allegory of the young nation of Canada, who mourns their dead. Edna Moynihan served as a model, the statue itself being designed by the Italian Luigi Rigamonti. The statue, a reference to the traditional images of the Mater Dolorosa and in a similar style to Michelangelo's Roman Pietà , faces east, i. H. into the dawn of the new day. Unlike the other statues on the memorial, the stonemasons formed Canada Bereft from a single 30-ton block of stone . The statue is the largest single piece of the monument and serves as the focal point. The area in front of the memorial was transformed into a leafy space, what Allward referred to as an amphitheater, which was fanned out from the front wall of the memorial to a distance of 270 meters, while the battle-marked landscape around the sides and back of the memorial remained untouched.

The twin masts rise up to a height of 30 meters above the stone platform of the memorial; the one wearing the Maple Leaf (Maple Leaf) for Canada and the other the Fleur-de-lis of France, and both symbolize the unity and the sacrifice of the two countries. At the top of the pylons is a grouping of figures known collectively as the chorus . The oldest figures represent justice and peace . Peace stands with a raised torch, making it the highest point in the region. The pair are similar in style to Allward's previously commissioned Statues of Truth and Justice that sit on the outside of the Supreme Court of Canada in Ottawa . The rest of the chorus is just below the older figures: Faith , Hope, and Truth on the eastern pylon; and honor , charity and knowledge on the western pylon. Around these figures are shields from Canada, Great Britain and France. Large crosses adorn the outside of each pylon. At the foot of the pylons are the battle honors of the Canadian regiments in World War I and a dedication message to Canada's war dead in French and English. The spirit of the victim is at the base between the two pylons. In it, a young dying soldier looks up in a crucifixion-like pose and hands his torch to a comrade, which is supposed to be a reference to the poem In Flanders Fields by John McCrae .

The Grieving Parents , a male and a female figure, lie on either side of the western staircase at the rear of the monument. Representing the grieving mothers and fathers of the nation, they are likely modeled on the four statues by Michelangelo on the Medici Chapel in Florence . The names of the 11,285 Canadians killed in France, whose final resting place is unknown, are inscribed on the outer wall of the monument. Most Commonwealth War Graves Commission memorials present the names of the war dead in a descending listing format in a manner that allows modification as the remains are found and identified. Allward tried to make the names a seamless list instead, and decided to do so by inscribing the names in continuous bands, using both vertical and horizontal seams, around the base of the monument. As a result, it has not been possible to remove memorial names without breaking the seamless list, and as a result there are people who both have a known grave and are listed on the memorial. The memorial contains the names of four posthumous recipients of the Victoria Cross: Robert Grierson Combe, Frederick Hobson, William Johnstone Milne, and Robert Spall.

Memorial to the Moroccan Division

The Moroccan Division Memorial is dedicated to the French and foreign members of the Moroccan Division who died during the Battle of Loretto in May 1915. The memorial was erected by division veterans and inaugurated on June 14, 1925, after being erected without a building permit. In addition to various memorial plaques on the lower front facade of the memorial, the battles in which the division took part are listed in the left and right corner views. The department's veterans funded the installation of a marble plaque in April 1987, identifying the Moroccan department as the only department in which all subordinate units had been awarded the Legion of Honor .

The Moroccan division comprised units of different origins and although the name suggests otherwise, it did not include units that came from Morocco . Moroccans belonged to the marching regiment of the Foreign Legion , which included tirailleurs and zouaves mainly from Tunisia and Algeria . The French legionaries came, as a plaque attached to the memorial testifies, from 52 different countries, including American, Polish, Russian, Italian, Greek, German, Czech, Swedish and Swiss volunteers, such as B. the writer Blaise Cendrars .

In the battle, General Victor d'Urbal , commander of the French 10th Army , tried to storm the German positions on Vimy Ridge and Notre Dame de Lorette. When the attack began on May 9, 1915, the French XXXIII. Army Corps significant territorial gains. The Moroccan Division, part of the XXXIII. Army Corps moved quickly through the German defenses and advanced into the German lines within two hours. The division managed to get the height of the ridge, with small groups even reaching the other side of the ridge before retreating for lack of reinforcement. Even after German counterattacks, the division was able to maintain a territorial gain of 2100 meters. However, the division suffered heavy losses. Among those killed in the battle, remembered by the memorial, were the division's two brigade commanders.

Grange Subway

The Western Front of World War I comprised an extensive system of underground tunnels, rail links, and shelters. The Grange Subway is a tunnel system that is approximately 800 meters long and once connected the reserve lines to the front line. This allowed the soldiers to advance quickly, safely and invisibly to the front. Part of this tunnel system is open to the public as part of regular tours offered by Canadian student guides.

The Arras-Vimy sector was conducive to tunneling due to the soft, porous but extremely stable nature of the chalky subsoil. As a result, extensive underground warfare has been a feature of this sector since 1915. In preparation for the Battle of Vimy Ridge, five British tunneling divisions dug twelve subways along the front of the Canadian Corps, the longest of which was 1.2 km in length. The tunnel builders built the underground railways at a depth of 10 meters to ensure protection from large-caliber self-propelled howitzers. The subways were often dug at a speed of four meters per day and were up to two meters high and one meter wide. This underground network contained concealed railway lines, hospitals, command posts, water reservoirs, ammunition stores, mortar and machine gun positions, and communication centers.

Lieutenant-Colonel Mike Watkins Memorial

Near the Canadian side of the restored trenches is a small plaque dedicated to Lieutenant-Colonel Mike Watkins. Watkins was the head of the 11th Explosive Ordnance Disposal Regiment RLC in the Royal Logistic Corps, and a leading British expert in ammunition and bomb disposal. In August 1998, he died in a roof collapse near a tunnel entrance while conducting a detailed survey of the UK tunnel system on the grounds of Canada's National Vimy Memorial. Watkins had previously been active in the tunnel system at Vimy Ridge, in the same year he participated in the successful defusing of 3 tons of ammonal explosives under a road crossing on the site.

Visitor center

The memorial has a visitor center with Canadian student guides that is open seven days a week. During the restoration, the original visitor center near the monument was closed and replaced with a temporary one. The visitor center is now located near the preserved front trench line and many of the craters created by underground mining during the war and near the entrance to the Grange Subway. The new educational visitor center was opened on the 100th anniversary of the battle. The visitor center is a public-private partnership between the government and the Vimy Foundation and cost approximately 10 million Canadian dollars. To raise funds, the Vimy Foundation has granted sponsors naming rights in various halls of the visitor center, an approach that has met with controversy due to the fact that it is a memorial park.

Socio-cultural influence

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial has great socio-cultural significance for Canada. The view that Canada's national identity and nationality emerged from the Battle of Vimy Ridge is widely shared in Canada's military and general historiography. Historian Denise Thomson suggests that the construction of the Vimy Memorial marks the culmination of an increasingly confident nationalism that developed in Canada during the interwar period. Hucker suggests that the memorial goes beyond the Battle of Vimy Ridge and now serves as a permanent image of the entire World War I, while expressing the enormous impact of the war in general, and also believes that the 2005 restoration project is evidence for the determination of a new generation to remember Canada's contribution and sacrifice during World War I.

The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada recognized the importance of the memorial by recommending its designation as one of the National Historic Sites of Canada ; it received recognition in 1996 and is one of only two outside Canada. Remembrance has taken other forms as well: the Vimy Foundation, which was created to preserve and promote Canada's World War I legacy, symbolized by victory in the Battle of Vimy Ridge, and Vimy Ridge Day to help the dead and To commemorate those injured during the battle.

The memorial is not without its critics. Alana Vincent has argued that the components of the monument are in conflict and therefore the message that the monument conveys is not consistent. Visually, Vincent argues that there is a dichotomy between the triumphant pose of the figures at the top of the pylons and the mourning posture of those figures at the base. Textually, she argues that the inscription text celebrating the victory in the Battle of Vimy Ridge strikes a very different tone than the list of names of those missing at the foot of the monument.

The memorial is regularly the subject of or inspiration for other artistic projects. In 1931, Will Longstaff painted the Ghosts of Vimy Ridge , which depicts the ghosts of men of the Canadian Corps on Vimy Ridge around the memorial, although the memorial was still a few years from completion. The memorial has been the subject of postage stamps in both France and Canada, including a French series from 1936 and a Canadian series commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Armistice in 1918 . The Unknown Soldier for a Canadian Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was selected from a cemetery near the Vimy National Monument, and the Canadian Tomb of the Unknown Soldier design is based on the stone sarcophagus at the base of the Vimy Monument. The Never Forgotten National Memorial was supposed to be a 24 meter tall statue inspired by the Canada Bereft statue on top of the memorial before the project was canceled in February 2016. A Canadian historical novel ("The Stone Sculptors") by Jane Urquhart incorporates the characters into the design and design of the monument. In 2007 the monument was in the selection for the so-called Seven Wonders of Canada . The Royal Canadian Mint issued commemorative coins with the memorial several times, including a 5-cent silver coin in 2002 and a $ 30 sterling silver coin in 2007. The Medal of Sacrifice, a Canadian award from 2008, features the image of Mother Canada on the back of the medal. A permanent bas-relief carved image of the memorial is displayed in the gallery of the great room of the French Embassy in Canada to symbolize the close ties between the two countries. The memorial is depicted on the front and back of the so-called Frontier Series, a Canadian twenty dollar banknote issued by the Bank of Canada on November 7, 2012.

literature

- Peter Barton, Peter Doyle, Johan Vandewalle: Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers' War 1914–1918 . McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal & Kingston 2004, ISBN 0-7735-2949-7 .

- Lynne Bell, Arthur Bousfield, Gary Toffoli: Queen and Consort: Elizabeth and Philip - 60 Years of Marriage . Dundurn Press, Toronto 2007, ISBN 978-1-55002-725-9 .

- Michael Boire: The Underground War: Military Mining Operations in support of the attack on Vimy Ridge, April 9, 1917 Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. (PDF) In: Laurier Center for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies (Ed.): Canadian Military history . 1, No. 1-2, Spring 1992, pp. 15-24. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- Michael Boire: The Battlefield before the Canadians, 1914-1916 . In Geoffrey Hayes, Andrew Iarocci; Mike Bechthold: Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment. Waterloo 2007: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Pp. 51-61. ISBN 0-88920-508-6 .

- Gordon Bolling: Acts of (Re-) Construction: Traces of Germany in Jane Urquhart's Novel the Stone Carvers . In Heinz Antor, Sylvia Brown, John Considine; Klaus Stierstorfer: Refractions of Germany in Canadian Literature and Culture . Berlin 2003: de Gruyter. Pp. 295-318. ISBN 978-3-11-017666-7 .

- Lane Borestad: Walter Allward: Sculptor and Architect of the Vimy Ridge Memorial . In: Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada (Ed.): Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada . 33, No. 1, 2008, pp. 23-38.

- Laura Brandon: Canvas of War . In: Briton Cooper Busch: Canada and the Great War: Western Front Association Papers . Montreal 2003, McGill-Queen's University Press. Pp. 203-215. ISBN 0-7735-2570-X .

- Laura Brandon: Art or Memorial? : The Forgotten History of Canada's War Art . University of Calgary Press, Calgary 2006, ISBN 1-55238-178-1 .

- Eric Brown, Tim Cook: The 1936 Vimy Pilgrimage . In: Laurier Center for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies (Ed.): Canadian Military History . 20, No. 2, Spring 2011, pp. 33-54.

- David Campbell: The 2nd Canadian Division: A “Most Spectacular Battle” . In: Geoffrey Hayes, Andrew Iarocci, Mike Bechthold: Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment . Waterloo 2007, Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Pp. 171-192. ISBN 0-88920-508-6 .

- Richard Cavell: Remembering Canada: The Politics of Cultural Memory . In: Cynthia Sugars: The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Literature. Oxford University Press, 2015. pp. 64-79. ISBN 978-0-19-994186-5 .

- Tim Cook: The Gunners of Vimy Ridge: We are Hammering Fritz to Pieces . In: Geoffrey Hayes, Andrew Iarocci, Mike Bechthold: Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment. Waterloo 2007, Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Pp. 105-124. ISBN 0-88920-508-6 .

- Santanu Das: Race, Empire and First World War Writing . Cambridge University Press, New York 2011, ISBN 978-0-521-50984-8 .

- Robert A. Doughty. Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operation in the Great War. Cambridge and London 2005, Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-01880-X .

- Denis Duffy: Complexity and contradiction in Canadian public sculpture: the case of Walter Allward . In: Routledge (Ed.): American Review of Canadian Studies . 38, No. 2, 2008, pp. 189-206. doi : 10.1080 / 02722010809481708 .

- Serge Durflinger: Safeguarding Sanctity: Canada and the Vimy Memorial during the Second World War . In: Geoffrey Hayes, Andrew Iarocci, Mike Bechthold: Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment. Waterloo 2007. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Pp. 291-305. ISBN 0-88920-508-6 .

- Suzanne Evans: Mothers of Heroes, Mothers of Martyrs: World War I and the Politics of Grief . McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal February 9, 2007, ISBN 0-7735-3188-2 .

- Tony Fabijančić: Croatia: Travels in Undiscovered Country . University of Alberta, 2003, ISBN 0-88864-397-7 .

- Don Farr: The Silent General: A Biography of Haig's Trusted Great War Comrade-in-Arms . Helion & Company Limited, Solihull 2007, ISBN 978-1-874622-99-4 .

- Andrew Godefroy: The German Army at Vimy Ridge . In: Geoffrey Hayes, Andrew Iarocci, Mike Bechthold: Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment . Waterloo 2007. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Pp. 225-238. ISBN 0-88920-508-6 .

- Geoffrey Hayes. The 3rd Canadian Division: Forgotten Victory . In: Geoffrey Hayes, Andrew Iarocci, Mike Bechthold: Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment . Waterloo 2007, Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Pp. 193-210. ISBN 0-88920-508-6 .

- J. Castell Hopkins: Canada at War, 1914-1918: A Record of Heroism and Achievement . Canadian Annual Review, Toronto 1919.

- Jacqueline Hucker. The Meaning and Significance of the Vimy Monument . In: Geoffrey Hayes, Andrew Iarocci, Mike Bechthold: Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment . Waterloo 2007. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Pp. 279-290. ISBN 0-88920-508-6 .

- Jacqueline Hucker: Vimy: A Monument for the Modern World . In: Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada (Ed.): Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada . 33, No. 1, 2008, pp. 39-48.

- Mark Osborne Humphries. 'Old Wine in New Bottles': A Comparison of British and Canadian Preparations for the Battle of Arras . In: Geoffrey Hayes, Andrew Iarocci, Mike Bechthold: Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment . Waterloo 2007. Wilfrid Laurier University. Pp. 65-85. ISBN 0-88920-508-6 .

- Dave Inglis: Vimy Ridge: 1917-1992, A Canadian Myth over Seventy Five Years . Simon Fraser University, Burnaby 1995 (Retrieved May 22, 2013).

- David Lloyd: Battlefield tourism: pilgrimage and the commemoration of the Great War in Britain, Australia and Canada, 1919-1939 . Berg Publishing, Oxford 1998, ISBN 1-85973-174-0 .

- Duncan E. MacIntyre: Canada at Vimy . Peter Martin Associates, Toronto 1967.

- Heather Moran. The Canadian Army Medical Corps at Vimy Ridge . In: Hayes, Geoffrey; Iarocci, Andrew; Bechthold, Mike: Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment . Waterloo 2007. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. Pp. 139-154. ISBN 0-88920-508-6 .

- Desmond Morton; Glenn Wright (1987): Winning the Second Battle: Canadian Veterans and the Return to Civilian Life, 1915-1930 . Toronto 2007. University of Toronto Press.

- Gerald WL Nicholson: Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF), Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationary, Ottawa 1962 (accessed January 1, 2007).

- Gerald WL Nicholson: “We will remember…”: Overseas Memorials to Canada's War Dead . Minister of Veterans Affairs for Canada, Ottawa 1973.

- John Pierce: Constructing Memory: The Vimy Memorial Archived from the original on March 5, 2009 (PDF) In: Laurier Center for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies (Ed.): Canadian Military History . 1, No. 1-2, Spring 1992, pp. 4-14. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- Peter Pedersen: ANZACS on the Western Front: The Australian War Memorial Battlefield Guide . John Wiley & Sons, New York 2012.

- Antoine Prost: Monuments to the Dead . In Pierre Nora, Lawrence Kritzman, Arthur Goldhammer: Realms of memory: the construction of the French past . New York 1997. Columbia University Press. Pp. 307-332. ISBN 0-231-10634-3 .

- Ken Reynolds, “Not A Man Fell Out and the Party Marched Into Arras Singing”: The Royal Guard and the Unveiling of the Vimy Memorial, 1936 . In: Canadian Military History . 17, No. 3, 2007, pp. 57-68.

- Ken Reynolds: From Alberta to Avion: Private Herbert Peterson, 49th Battalion, CEF . In: Canadian Military History . 16, No. 3, 2008, pp. 67-74.

- Edward Rose, Paul Nathanail: Geology and Warfare: Examples of the Influence of Terrain and Geologists on Military Operations . Geological Society, London 2000, ISBN 0-85052-463-6 .

- Mart Samuels: Command or Control ?: Command, Training and Tactics in the British and German Armies, 1888-1918 . Frank Cass, Portland 1996, ISBN 0-7146-4570-2 .

- Nicholas Saunders: Excavating memories: archeology and the Great War, 1914-2001 . In: Portland Press (Ed.): Antiquity . 76, No. 291, 2002, pp. 101-108.

- Jack Sheldon: The German Army on Vimy Ridge 1914-1917 . Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley (UK) 2008, ISBN 978-1-84415-680-1 .

- Peter Simkins, Geoffrey Jukes, Michael Hickey: The First World War: The Western Front, 1917–1918 . Osprey Publishing, 2002, ISBN 978-1-84176-348-4 .

- Julian Smith: Restoring Vimy: The Challenges of Confronting Emerging Modernism . In: Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada (Ed.): Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada . 33, No. 1, 2008, pp. 49-56.

- Denise Thomson: National Sorrow, National Pride: Commemoration of War in Canada, 1918–1945 . In: Journal of Canadian Studies . 30, No. 4, Winter 1995-1996, pp. 5-27.

- Spencer Tucker (Ed.): The European powers in the First World War: an encyclopedia . Garland Publishing, New York 1996, ISBN 0-8153-0399-8 .

- Alexander Turner: Vimy Ridge 1917: Byng's Canadians Triumph at Arras . Osprey Publishing, London 2005, ISBN 1-84176-871-5 .

- Jonathan Franklin Vance: Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning, and the First World War . UBC Press, Vancouver 1997, ISBN 0-7748-0600-1 .

- Philippe Vincent-Chaissac: Moroccans, Algerians, Tunisians… From Africa to the Artois , They Came from Across the Globe, L'Echo du Pas-de-Calais, p. 3.

- Alana Vincent. Two (and two, and two) Towers: Interdisciplinary, Borrowing and Limited Interpretation . In: Heather Walton: Literature and Theology: New Interdisciplinary Spaces . Ashgate 2011. pp. 55-66. ISBN 978-1-4094-0011-0 .

- Alana Vincent: Making Memory: Jewish and Christian Explorations in Monument, Narrative, and Liturgy . James Clarke & Co, 2014, ISBN 978-0-227-17431-9 .

- Jeffery Williams: Byng of Vimy, General and Governor General . Secker & Warburg, London 1983, ISBN 0-436-57110-2 .

Web links

- Official website

- Vimy Ridge National Historic Site of Canada. Canadian Register of Historic Places, accessed August 11, 2018 .

- The Vimy Foundation

- Radio recording of King Edward VIII's speech at the opening

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWG): Vimy Memorial

- Canadians on Vimy Ridge 1940

- Return to Vimy

- Veterans Affairs Canada - Vimy Ridge 100th Anniversary

Individual evidence

- ↑ Farr 2007, p. 147; Rose & Nathanail 2000, pp. 396-397, Fig. 14.3.

- ↑ Boire 2007, p. 56; Tucker 1996, pp. 8, 68.

- ↑ Farr 2007, p. 147; Boire 1992, p. 15; Samuels 1996, pp. 200-202.

- ^ Cook 2007, p. 120; Nicholson 1962, p. 229; Turner 2005, p. 39; Williams 1983, p. 149.

- ↑ Nicholson 1962, p. 255; Campbell, p. 178 f .; Hayes 2007, p. 209

- ↑ Hayes 2007, p. 202 f.

- ↑ Godefroy 2007, p. 220; Sheldon 2008, p. 309.

- ↑ Campbell 2007, p. 179

- ↑ Campbell 2007, p. 179 ff.

- ↑ Campbell 2007, p. 182.

- ↑ Godefroy 2007, p. 220.

- ↑ Nicholson 1962, p. 263

- ↑ Nicholson 1962, p. 263.

- ↑ Moran 2007, p. 139.

- ^ Philip Gibbs: All of Vimy Ridge Cleared of Germans (PDF). In: The New York Times , The New York Times Company, April 11, 1917. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ↑ Inglis 1995, p. 1; Vance 1997, p. 233; Pierce 1992, p. 5.

- ↑ Inglis 1995, p. 2; Humphries 2007, p. 66

- ↑ Brandon 2003, p. 205.

- ^ A b Canadian Battlefields Memorials Committee . Veteran Affairs Canada. March 25, 2007. Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- ↑ Brandon 2003, p. 205.

- ↑ Vance 1997, p. 66.

- ↑ Hucker 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ Design Competition . Veteran Affairs Canada. March 25, 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ↑ Borestad 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Vance 1997, p. 67.

- ↑ Borestad 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Vance 1997, p. 67.

- ↑ Vance 1997, p. 66.

- ↑ Borestad 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Hucker 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ Pierce 1992, p. 5.

- ↑ Hucker 2007, p. 283

- ↑ Borestad 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Vance 1997, pp. 66-69.

- ↑ Inglis 1995, p. 61.

- ↑ a b Canada Treaty Information . Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. February 26, 2002. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved on January 4, 2008.

- ↑ Borestad 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Hucker 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ Hucker 2007, p. 286.

- ↑ Hucker 2007, p. 286.

- ↑ Fabijančić 2003, p. 127.

- ↑ Hucker 2007, p. 286.

- ↑ Hucker 2007, p. 285.

- ↑ Durflinger 2007, p. 292.

- ↑ Hucker 2007, p. 286.

- ^ The Battle of Vimy Ridge - Fast Facts . In: VAC Canada Remembers . Veterans Affairs Canada. n. d .. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ↑ Hucker 2007, p. 286.

- ↑ Business Information Group: [www.canadianarchitect.com/news/restaurierung-loss-at-vimy/1000204056/].

- ^ Design and Construction of the Vimy Ridge Memorial . Veterans Affairs Canada. August 12, 1998. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ↑ Duffy 2008, p. 197.

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, pp. 4, 42.

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, p. 41

- ↑ MacIntyre 1967, p. 197.

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, p. 42.

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, p. 42.

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, p. 42

- ↑ Reynolds 2007, p. 68.

- ↑ Cook 2017, pp. 258-261

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, p. 46.

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, pp. 37-38.

- ^ Tim Cook: The event that recast the Battle of Vimy Ridge . In: Toronto Star , April 2, 2017. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ↑ Evans 2007, p. 126.

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, p. 42.

- ↑ John Mold Diaries: Return to Vimy . Archives of Ontario . n. d .. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, p. 51.

- ↑ Morton, Wright 1987, p. 221.

- ↑ Brown, Cook 2011, pp. 46 f., 51 f.

- ↑ Durflinger 2007, p. 292 ff.

- ^ "The Canadian Unknown Soldier". After the battle. Battle of Britain Intl. Ltd. (109). ISSN 0306-154X.

- ↑ Inglis 1995, pp. 92, 107

- ↑ Patrick Doyle: Vimy Ridge 'sacrifice' forged unity PM explained . In: Toronto Star , April 10, 1992, p. A3.

- ↑ Tom MacGregor: Return To The Ridge . Royal Canadian Legion. September 1st, 1997. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Ceremony marks 85th anniversary of Vimy Ridge battle , Canadian Press. April 7, 2002.

- ↑ a b c d e f Michael Valpy (April 7, 2007): Setting a legend in stone . In: The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Accessed: August 9, 2018.

- ↑ Hucker 2007, p. 288

- ↑ Smith 2008, p. 52

- ^ Tom Kennedy, (April 9, 2007). National News. CTV Television Network.

- ↑ Alicja Siekierska: Toronto Photographer opens exhibition commemorating the Battle of Vimy Ridge . Toronto Star. March 31, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- ^ The Canadian Press: Canadian and French leaders pay homage to fallen soldiers on Vimy Ridge . National Newswatch Inc. April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ↑ Vimy Ridge: Royals remember the definition of the battle in the first World War . BBC. April 9, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2017.

- ^ François Hollande et Bernard Cazeneuve confirment leur venue à Vimy le 9 avril . Le Voix du Nord. March 25, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- ↑ Bruce Deachman: Governor General, French Ambassador unveils Vimy anniversary stamps . March 22, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ↑ Rose, Nathanail 2000, p. 216

- ↑ Lloyd 1998, p. 120

- ↑ Annual Report 2007–2008 (PDF) Commonwealth War Graves Commission. 2008. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ↑ Turner 2005, p. 7

- ↑ CWGC :: Cemetery Details - Canadian Cemetery No. 2, Neuville-St. Vaast . Commonwealth War Graves Commission. n. d .. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ↑ CWGC :: Cemetery Details - Givenchy Road Canadian Cemetery, Neuville-St. Vaast . Commonwealth War Graves Commission. n. d .. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ↑ Saunders, pp. 101-108

- ^ Interpretive Center at the Canadian National Vimy Memorial . Veterans Affairs Canada. March 22, 2007. Archived from the original on November 13, 2007. Retrieved on November 14, 2009.

- ^ Canadian Battlefield Memorials Restoration Project . Veterans Affairs Canada. January 19, 2007. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ↑ Pierce 1992, p. 6.

- ↑ Brandon 2006, p. 10

- ↑ Hopkins 1991, p. 188

- ↑ Hucker 2008, p. 46.

- ↑ Brandon 2006, p. 10.

- ↑ Brandon 2006, p. 13

- ↑ Brandon 2006, p. 12.

- ↑ Vincent 2011, p. 59.

- ↑ Duffy 2008, p. 194.

- ↑ Nicholson 1973, p. 33.

- ↑ Brandon 2006, p. 12

- ^ Victoria Cross (VC) Recipients . Veterans Affairs Canada.

- ↑ a b Stéphanie Trouillard: Grande Guerre: la Division marocaine qui n'avait de marocaine que le nom . France May 24th, 6th 2015.

- ^ Monument aux morts de la division marocaine . Lens-Liévin Tourist Information and Cultural Heritage Office. n. d ..

- ^ Forgotten Heroes North Africans and the Great War 1914-1919 . Forgotten Heroes 14-19 Foundation. Archived from the original on October 19, 2014.

- ↑ Vincent-Chaissac, p. 33.

- ↑ Vincent-Chaissac, p. 33.

- ↑ Das 2011, p. 316

- ↑ Vincent-Chaissac, p. 33.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p. 159.

- ↑ Simkins, Jukes, Hickey 2002, p. 48.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, p. 159.

- ↑ Boire 2007, p. 56.

- ↑ Barton, Doyle, Vandewalle 2004, p. 200.

- ↑ Rose, Nathanail 2000, p. 398.

- ^ Paul Beaver: Obituary: Lt-Col Mike Watkins . In: The Independent . August 14, 1998. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- ↑ Visitor information . Veterans Affairs Canada. n. d .. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved on February 10, 2016.

- ↑ Pedersen, Chapter 7

- ^ Vimy Ridge Memorial in France to get visitor center . Global News. May 14, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Blair Crawford: Corporate branding will be 'subtle' and 'tasteful' at new Vimy Ridge center in France . Ottawa Citizen. January 11, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ↑ Hucker 2007, p. 280.

- ↑ Mission . Vimy Foundation. n. d .. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Will Longstaff's Menin Gate at midnight (Ghosts of Menin Gate) . Australian War Memorial. n. d .. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ↑ Mick Bister: The 1936 'Vimy Ridge' Issue (259). Journal of the France and Colonies Philatelic Society, March 2011.

- ^ Designing and Constructing . Veterans Affairs Canada. May 5, 2000. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ Parks Canada backs out of controversial 'Mother Canada' was a memorial project in Cape Breton . In: National Post . February 5, 2016. Retrieved February 8, 2016.

- ↑ Cavell 2015, p. 68 f.

- ^ Vimy Memorial, France . Canadian Broadcasting Corporation . Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ New military medal to honor combat casualties . Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. August 29, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ↑ Embassy of France in Canada, virtual visit . Embassy of France in Canada. January 2004. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ↑ Twenty Dollar Bill . CTV. n. d .. Retrieved May 6, 2012.