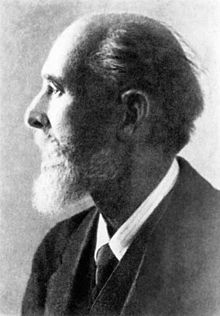

Peter Carl Fabergé

Peter Carl Fabergé ( Russian Петер Карл Фаберже ; born May 18 . Jul / 30th May 1846 greg. In St. Petersburg ; † 24. September 1920 in Pully in Lausanne ) was a Russian goldsmith and jeweler . He achieved fame for his extremely artistic and masterfully crafted pieces of jewelry and decorative objects, in particular the so-called Fabergé eggs .

Life

Family and youth

Fabergé's father was the goldsmith and jeweler Gustav Fabergé (1814–1893), whose Huguenot ancestors had emigrated from Picardy to Schwedt in Brandenburg in 1685 and to the Russian Baltic region of Livonia around 1800 . His mother Charlotte Marie, née Jungstedt, was the daughter of a Danish painter. In 1842, his father had opened a goldsmith's workshop and jewelry store on 12 Bolshaya Morskaya Street in St. Petersburg. In his hometown, Fabergé attended the German-speaking Protestant Annenschule .

The family moved to Dresden in 1860 , where their two sons Peter Carl and Agathon (1862–1895) received their education. Peter Carl Fabergé was confirmed in 1861 in the Kreuzkirche . He attended the Dresden business school in order to prepare for the commercial management of the business and regularly visited the treasures of the Green Vault . This was followed by educational trips to well-known jewelers in England, Italy and above all Paris (including Cartier and Boucheron ), studies at the Paris commercial school and a short goldsmith apprenticeship in Frankfurt. Fabergé returned to St. Petersburg in 1864, where he continued his training with Hezekiah Pendin, friend and partner of his father. Finally, in 1872, he took over the management of his father's jewelry store himself. In the same year he married Augusta Julia Jacobs (1851-1925), daughter of the Swedish-born court carpenter Gottlieb Jacobs, with whom he had four sons.

Career as a jeweler

At first Fabergé worked as a jeweler, next to it in the St. Petersburg Hermitage . Together with his brother, he repaired the extensive jewelry collection, restored numerous pieces, valued their value and cataloged them. This activity inspired the Fabergés to recreate jewelery in the old Russian style and to make them in their own workshop, sometimes as true-to-original copies. This business strategy brought them their first successes.

The breakthrough came with the Fabergés after they had some valuable works on the Emperor Alexander III at the All-Russian Exhibition in Moscow in 1882 . could sell. For the first of the Fabergé eggs, he awarded Peter Carl Fabergé a gold medal. The atelier owed this honor, among others. Eric Kollin, a Finnish goldsmith who had the idea of combining traditional Russian Easter customs with goldsmithing.

As a result, a Fabergé egg was created for every Easter festival , which was given as a gift to Empress Maria Fjodorovna, née Dagmar of Denmark . Fabergé won renowned master jewelers such as Michail Jewlampjewitsch Perchin and Henrik Wigström . After 1895, Alexander's son and successor Nicholas II had two eggs made each, which he gave to Empress Alexandra Fjodorovna, née Alix von Hessen-Darmstadt, and his mother.

With the crown jewels , the official coronation gifts to Nicholas II and many works commissioned by the tsar's family, mostly true-to-original copies - not even the tsar himself could distinguish his tobacco box from a replica for use in the summer residence - most of the works were created by 1916 Fabergés, who now bore the title of Imperial Court Jeweler . At the height of its success, when Fabergé made silverware , table clocks and decorative sculptures as well as metal carvings based on models of Russian folk art - but also cheap costume jewelry in "Western" style from series production with rhinestones and base metals - the family had branches in Moscow , Odessa , Kiev and London with more than 700 employees, including 500 at the headquarters in Saint Petersburg. Around 150,000 pieces were made between 1882 and 1917. In 1897 the Swedish royal family awarded Peter Carl Fabergé the title of Royal Court Goldsmith. In 1898 he made a huge silver, richly gilded and enameled vase in "old Russian style" for Émile Zola . It had been commissioned by officers of the garrison in Orel as well as by large landowners and bore a Russian inscription (translated: "Long live Zola! Long live law and truth!").

His work was Russia's contribution to the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900 .

Exile and death

The October Revolution of 1917 made it impossible to continue the business: Fabergé was expropriated and its factories and shops were "nationalized". In 1918 he was forced to flee to Finland and later to Wiesbaden . His life's work was destroyed, which weighed heavily on him and dramatically worsened his health. Fabergé died in Lausanne , Switzerland and was buried with his wife Augusta at the Cimetière du Grand Jas in Cannes . His sons Eugène and Alexander re-founded the jewelry company after his death.

Fabergé in the 20th and 21st centuries

The Fabergé tradition was taken up again from 1989 to 2009 by the Pforzheim jewelery manufacturer Victor Mayer - as the only Fabergé authorized master craftsman - after a long break. During these two decades, workpieces were created using the same craft techniques, which are now extremely rare.

The first Fabergé egg to be officially returned to the Kremlin after the October Revolution was the “Gorbachev Peace Egg”, which was presented to the former President of the Soviet Union in 1991 when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize . The Gorbachev Peace Egg, made of gold, silver, enamel , diamonds and rubies , is limited to five copies. Only two copies are exhibited worldwide: Gorbachev's personal copy in the Kremlin armory in Moscow and the factory copy that was handed over to the Schwabach City Museum in 1993 .

The reintroduction of Fabergé in Russia was celebrated at Easter 2001 on April 12th at a gala event in the Kremlin Armory. The exhibits in the armory of the Kremlin also include the most elaborate egg object ever created by foreman Victor Mayer for Fabergé: the "moon phase egg". It took the artisans more than 18 months to complete. The work of art shows the phases of the moon in a dome made of cut rock crystal , the hours are displayed in a small viewing window made of rock crystal.

In 2009, Fabergé ended the licensing practice and took direct control of the design, manufacture and distribution . Victor Mayer remains an important supplier for Fabergé.

One of the most important private collections of Fabergé eggs was that of the American media entrepreneur Malcolm Forbes . In 2004, his heirs sold the nine eggs to the Russian businessman Wiktor Wekselberg for around 90 to 120 million US dollars . Together with other items from his Link of Times collection, the eggs will be exhibited in the Shuvalov Palace in Petersburg.

The Fabergé Museum in Baden-Baden was opened on May 9, 2009 .

literature

- John Booth: The art of Fabergé . Quantum Books, London 2005, ISBN 1-84573-069-0 .

- Christopher Forbes et al .: Fabergé. The imperial ceremonial eggs . Prestel, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7913-3019-5 .

- Géza of Habsburg-Lorraine: Fabergé - Cartier. Rivals at the Tsar's court . Hirmer, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-7774-9830-0 .

- Géza von Habsburg-Lothringen: Fabergé yesterday and today . Hirmer, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-7774-2465-X .

- Géza von Habsburg-Lothringen et al .: Precious Easter eggs from the Tsarist Empire. From the AP Goop collection, Vaduz . Hirmer, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-7774-8020-7 .

- Kenneth Snowman: Carl Fabergé, goldsmith to the imperial court of Russia . Faber & Faber, London 1979, ISBN 0-905649-13-3 .

- Elsebeth Welander-Berggren: Carl Fabergé . National Museum, Stockholm 1997, ISBN 91-7100-539-0 .

- Catalog of the pictorial works 1780–1920 of the Stadtmuseum Berlin Foundation (LETTER Schriften Vol. 14), edited by Knut Brehm, Bernd Ernsting, Wolfgang Gottschalk and Jörg Kuhn, Cologne 2003 (including portraits of Carl and Eugene Fabergé by Josef Limburg ).

- Knekties, Ina: Fabergé. The Ivanov Collection . In collector's journal 2013, issue 3, pp. 24–31

Web links

- Literature by and about Peter Carl Fabergé in the catalog of the German National Library

- Baltic Historical Commission (ed.): Entry on Peter Carl Fabergé. In: BBLD - Baltic Biographical Lexicon digital

- Official website of FABERGÉ

- Peter Carl Fabergé at Google Arts & Culture

- Fabergé Museum Baden-Baden

- Stadtmuseum Stadt Schwabach, Folklore Egg Collection Department "Heer-Maynollo"

- Fabergé works in museums in the USA

- Fabergé - magic made of gold and precious stones - report on 3sat

Individual evidence

- ^ A. Kenneth Snowman: The Art of Carl Fabergé. Faber and Faber, London 1953, p. 29.

- ↑ Toby Faber: Faberge's Eggs. One Man's Masterpieces and the End of an Empire. Macmillan, 2008.

- ^ A. Kenneth Snowman: The Art of Carl Fabergé. Faber and Faber, London 1953, p. 30.

- ↑ Political Review. In: Bregenzer Tagblatt / Vorarlberger Tagblatt , March 12, 1898, p. 1 (online at ANNO ).

- ^ Factory copy of the Gorbachev peace ice cream in Schwabach

- ↑ From Forbes to Wechselberg. ( Memento from July 28, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: art - Das Kunstmagazin . Issue 4/2004. P. 126 - Link is no longer active

- ↑ History of the collection on www.fabergemuseum.ru (English)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Faberge, Carl Peter |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Fabergé, Peter Carl; Фаберже, Петер Карл (Russian) |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Russian goldsmith and jeweler |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 30, 1846 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | St. Petersburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 24, 1920 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Lausanne |