Charley Patton

|

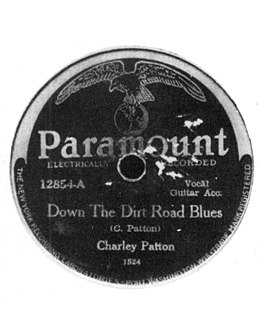

| Down The Dirt Road Blues , label, 1929 |

Charley Patton , also Charlie Patton (* April (?) 1891 near Bolton , Mississippi , USA ; † April 28, 1934 in Indianola , Mississippi) was an American blues musician . He is considered the "father of the Delta Blues ".

Patton was active as a musician from around 1907 until his death, and from 1912 onwards, his influence on other blues musicians became apparent. In the early 1920s he was able to leave behind being a traveling musician and became the first star of the young genre. He recorded most of his well-known repertoire in three recording sessions in 1929 and 1930, through which he was able to increase his popularity even further. After a slump in his career due to the global economic crisis, he was given the opportunity to record again in 1934, but died shortly after this session. A total of 54 pieces by Patton have been preserved; they were all published (along with extensive other materials) in 2001 in the work edition Screamin 'and Hollerin' the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton . This box set was awarded three Grammys and made Patton known beyond professional circles for the first time.

The critic Robert Santelli wrote of him: “Patton's role in the history of the blues is immense; no country blues musician, save Blind Lemon Jefferson , had a greater impact on the future of the genre and the generation of stylists that followed than Patton. Everyone from Son House , Howlin 'Wolf , Tommy Johnson and Robert Johnson to Muddy Waters , John Lee Hooker and Elmore James can trace their blues style back to Patton. "

Life

Childhood and youth

Patton was the third oldest child of Bill and Annie Patton, most likely born in Bolton, Mississippi in April 1891 and had eleven siblings, eight of whom died during childhood and adolescence. The family was of mixed Native American, African American, and white origins.

Sam Chatmon claimed to be Patton's biological brother, pointing out that his father Henderson Chatmon had a relationship with Annie Patton in the early 1890s. Most likely one of the Pattons' sons was actually a child of Henderson Chatmon, but which of the three it was can no longer be definitely decided. The fact that William “Will C.” Patton (* 1895) is not listed as a child of the Pattons in the census records of 1900, however, allows the conclusion that Bill Patton did not name him as an illegitimate son and thus dismissed Charley Patton gone.

Between 1901 and 1904, Bill Patton and his family moved (after a brief interlude near Edwards in the mid-1990s) to the Dockery Plantation near Ruleville in the Mississippi Delta, which was reclaimed at that time, because of the considerably better income opportunities . The plantation was over sixty square kilometers, employed several hundred workers who lived with their families on the site and had its own, village-like infrastructure, including a dry goods store, a furniture store, a church, a cemetery and even a train station. There, the hard-working Bill Patton achieved relative prosperity, which for Charley also meant that his father enabled him to have a good upbringing - for his time and social position - he attended school up to ninth grade.

In addition to the school education, the father, himself an elder of the Baptist Church of Dockery Plantation, also attached great importance to a solid religious education for his children. Charley Patton attended Sunday School regularly, was Bible versed, and occasionally gave lay sermons. This religious training had a strong influence on Patton. He was drawn to the profession of preacher throughout his life, and religious themes also played an important role in his repertoire.

Patton began to play the guitar when he was seven years old and first had to fight for his love of music against his pious father, who even tried to drive it out by whipping him with a bull whip , since dance music was considered a sin for him as a Baptist. Ultimately, however, he gave in and gave Charley his first own guitar around 1905. His playing remained amateurish, however, until he met Henry Sloan on the Dockery Plantation , the earliest blues musician known by name, whose student he became and whom he accompanied for several years as a second guitarist. Another teacher from Patton was Earl Harris , whose influence on Patton cannot be precisely determined.

Patton occasionally played waltzes , ragtime , minstrel and also square dance music with the Chatmon Brothers , who later had great success as The Mississippi Sheiks . In 1906, when he was just under fifteen, he left his parents' home, probably due to drastic differences and arguments between him and his brother Willie.

Career start

Patton was active as a musician around 1907, Ernest Brown reports that he gradually became a local notoriety over the next four years. It is also interesting to note that Patton was already playing "the same kind of music as when he was making records" ( "He [was] playin 'the same kind of music like he did when he put out them records." ). The oldest compositions of his recorded repertoire date back to this time ( Pony Blues, Banty Rooster Blues, Mississippi Bo Weavil Blues, Down The Dirt Road ), by 1910 he had already composed almost all of the pieces that he was supposed to record at his first recording session in 1929. Around 1912 he stayed a lot in the small town of Drew, where he met numerous other musicians who would later become known (Howlin 'Wolf, Willie Brown , Tommy Johnson, Roebuck Staples ). John Fahey suspects that this was the beginning of his massive influence on the emerging Delta Blues. A few years later, a black US soldier shot a white man in Drew, which quickly worsened the climate for the musicians and ultimately had to leave the city. This excerpt from the musicians who were directly influenced by Patton meant that the style he had a decisive influence on spread widely in Mississippi.

In 1916, WC Handy offered him the opportunity to join his band, which he turned down because he could not read notes. During an examination for his suitability for service as a soldier in World War I , he learned that he had a heart defect ( mitral stenosis ) and was released from military service. In the course of the 1920s he became a well-known and popular solo musician in the southern United States, who - unlike his wandering colleagues - was already booked and paid for performances. Patton started out at juke joints , on street corners or in front of shops, at house parties (a private apartment or a house turned into a juke joint for one night), and at picnics that white farmers occasionally hosted for their black employees in his career sometimes for medicine shows , birthdays and weddings.

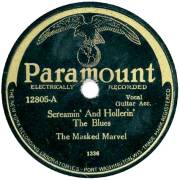

The first recording session

In 1929 the talent scout HC Speir had heard of him , presumably through Bo Carter , went to see him and, after a first test recording, tried to convey him to Victor Records . But Victor showed no interest in Patton and so Speir put him in charge of $ 150 commission to Paramount Records , which invited Patton to his first recording session in Richmond , Indiana . All fourteen pieces recorded there on June 14th (and 15th?) Were released within the next few months by Paramount, and one of the oldest pieces in his repertoire was released as a debut, the more than twenty year old “Pony Blues” . It should be his biggest sales success. Patton's second record, "Screamin 'And Hollerin' The Blues / Mississippi Bo Weavil Blues" , was released as a publicity stunt under the pseudonym "The Masked Marvel" , and whoever guessed Patton's identity could get a free record from the range win from Paramount.

Patton traveled to this session with Buddy Boy Hawkins , who had his last session here; on one of the songs that Hawkins recorded ( "Snatch It And Grab It" ) Patton can be heard singing and calling in the background.

The second recording session

Since Patton's first recordings had sold extremely well, he was brought in by Paramount for further recordings in November / December 1929, this time in Grafton , Wisconsin. He was accompanied by the multi-instrumentalist Henry Sims , who was not a recognized blues musician at the time, but whom he had known since his youth and had brought him to Paramount. Patton recorded twenty-four pieces, on six he is accompanied by Sims on the fiddle , in return he can be heard as guitarist on Sims' four recorded pieces.

The high number of recorded pieces - compared to other contemporary blues musicians - shows on the one hand his professionalism (normally only around four to eight pieces by a musician were recorded in one day, an average that Patton far surpassed in these sessions) and on the other hand his outstanding position that he had in Paramount's portfolio, such a high number of recordings by an artist in such a short time was absolutely unusual. With the death of Blind Lemon Jefferson in December 1929, Patton finally became Paramount's most prominent and successful artist, and thirteen records were to appear in the following year, more than any other blues artist.

The third recording session

Patton's third recording session also took place in Grafton in August 1930 and lasted four to six days. It was the last one for Paramount Records, which was already in financial difficulties due to the global economic crisis and the resulting lack of buyers for their records and had to close two years later. At the same time it was Patton's "smallest" session, he only recorded four pieces there, on which he is accompanied by Willie Brown as the second guitarist and which are often counted among his best recordings (the small number of recordings was probably due to this that Paramount wanted to contract Patton for a further year at this meeting).

At the request of Art Laibley, Paramount's production manager, Patton had brought more musicians to this session, all of whom were also given the opportunity to record (for which Patton received $ 100). Son House (whom Patton had only recently met) was able to make his first and only recordings for decades, as did Willie Brown (who never recorded again after his four pieces). Other lesser-known artists Patton brought with her were singer and pianist Louise Johnson (a brief lover of Patton who also recorded four pieces) and the a capella gospel group Delta Big Four .

Career slump

Due to the global economic crisis, poverty spread among the Afro-American population, which left little money for leisure activities and records. Patton did not get any further recording opportunities for the time being and gave guitar lessons at times. Remarkably, he played more often than ever before in front of a white audience, which on the one hand still had more financial means for festivities of all kinds and among whom he became increasingly popular in the last years of his life.

Last recording session and death

In 1933 the American record industry had recovered to some extent from the crisis and Patton, who had no record label, was offered a contract by the American Record Company (ARC) in January 1934 . Patton therefore traveled with his then partner Bertha Lee to his last recordings from January 30th to February 1st in New York and recorded 29 tracks there, partly together with Bertha.

Due to the fact that ARC records were barely available in Mississippi, the main focus of Patton's fame, Patton's releases were slow to sell, with only 12 of the 29 tracks appearing on Vocalion Records , a budget sub-label of ARC. His last (posthumous) publication, Hang It On The Wall , appeared in April 1935. The masters of the unpublished seventeen pieces are lost.

The recordings of this last session are audibly overshadowed by Patton's poor health. He had a bad cold and his voice was attacked (in 1933, a listener in Holly Ridge who understood the lyrics of a Patton song as an attempt to get on with his partner tried to cut his throat. Patton only barely survived but left a large scar on his throat back.). In addition, Patton had had severe heart problems shortly before his trip to New York, but made the trip regardless.

|

Don't the moon look pretty,

Shinin 'down through the tree? "Poor Me" |

Doesn't the moon look pretty

How does it seem down through the tree? |

His voice had become short of breath and brittle, it lacked the previous volume and flexibility. On the guitar he was no longer as powerful and fast as before, albeit more nuanced; many of the pieces were quieter, more introverted, and more serious. In some pieces Patton seems to want to end with the life he sang so wildly so far, lines like "Oh Death / I know my time ain't long" ( Oh Death ) or verses from Poor Me (see box on the right ) seem to indicate that Patton foresaw his impending death.

His restless lifestyle, combined with the increasing symptoms of a then untreatable mitral stenosis (which could be traced back to either syphilis connata or a rheumatic fever in his childhood), had drained Patton's physical resources over the years, and his health became increasingly worse. About two months after his last recordings, on April 28, 1934, Patton died of heart failure after a week's agony and constant preaching about the Revelation of John . His death went blank in the press and although many attended his funeral, no blues musician was present. His tombstone today honors him as “The Voice of the Delta” and “The foremost performer of early Mississippi Blues, whose songs became cornerstones of American music.” (“The leading artist of the early Mississippi Blues, whose Songs became the cornerstones of American music. ”).

Around the time of Patton's death, the country blues began to decline, many former venues relied on jukeboxes rather than unknown live artists, numerous musicians went to the cities and developed the new styles of urban blues there , a development that was reinforced by the adaptation of the electric guitar.

Family relationships

Patton, who is described as charismatic and handsome (he was about 5 feet tall, weighed around 65 pounds, had light brown skin and curly hair) and was both successful and relatively wealthy, was very attractive to women according to contemporary reports. He had numerous affairs, an unexplained number of so-called "common-law wives" (steady life partners, with whom he was not officially married, however - as was often the case with African-American couples at the time) and was married six times. However, the sources in this regard can only be described as confused; in addition to the six mentioned marriages, there may have been more, and there are indications for at least two. His first marriage was in 1908 with Gertrude Lewis, but the marriage was very short-lived, because in the same year he married Millie Bonds (unproven), who gave birth to a daughter, Willie Mae, known as China Lou. Although the "marriage" lasted only a few years, he remained in (loose) contact with her and China Lou. He married Dela Scott in 1913, Roxie Morrow in 1918 (with whom he had his longest marriage), Minnie Franklin in 1922, Mattie Parker in 1924 and Bertha Reed in 1926.

In addition to China Lou, Patton had numerous other children, two sons (* 1916 and 1918) with Sallie Hollins, with Martha Christian a daughter Rosetta (* 1917) (Patton's last surviving child, according to the birth certificate she was born in wedlock, a marriage certificate exists However not). Nothing else is known about the two children who emerged from his marriage to Bertha Reed, nor about a boy who is said to have died in early childhood.

Probably in late 1929 he met his last wife and occasional singing partner Bertha Lee Pate, known as Bertha Lee, a cook who was only thirteen at the time. From 1930 he lived with her in a spirited relationship that was partly marked by mutual violence, but both considered positive. A particularly tough argument at a house party between the two even led to a brief imprisonment for both of them in Belzoni prison (the story dealt with Patton in "High Sheriff Blues" ). In 1933 he moved in with her in Holly Ridge, Mississippi, and they stayed together until shortly before his death.

personality

Patton is portrayed in reports from relatives and contemporaries as generally humorous to the point of silliness but aloof, valiant, stubborn, and argumentative. Under the influence of alcohol (Patton drank a lot and often) these traits seem to have taken to extremes, his humor became caustic and mean and although he usually did not provoke physical arguments, he did not avoid them.

He avoided close relationships, he always kept a certain distance in his few friendships and rarely became private, his partnerships were obviously mostly fleeting in nature and without great emotional depth. He behaved condescendingly and disdainfully towards his partners in words and deeds, exploited some financially, and again and again he suffered from - sometimes extreme - domestic violence.

He was mostly dismissive and distant towards other musicians. If he had been drinking, he began to disturb and irritate other musicians more often with appearances by constant, apparently cheering interjections. During Louise Johnson's recording session in August 1930, he even did this in the studio, together with Son House, can be clearly heard in the fourth verse of "Long Way From Home", as Johnson then stutters due to the constant interruptions.

Patton was not a sedentary person, he changed his place of residence frequently in his life, but ( apart from two stays in Arkansas in the early 1910s and Memphis in the early 1930s) he always stayed in the extended surroundings of Dockery Plantation or his place of birth, which were his main living quarters . His travels took him to numerous places in Mississippi and the neighboring states, but occasionally further away from home (including Milwaukee , Chicago , St. Louis and Albany ).

Throughout his adult life, Patton worked exclusively as a musician and avoided physical labor. Being a musician made him free from any outside control and at the same time proved to be extremely profitable. Due to the frequency of his performances and his fame, he was arguably the only Delta Blues musician at his wedding who could live exceptionally well on his music alone, projections put his income from the recordings for 1929 alone as almost on the level of an American college professor ($ 2850 to $ 3150 ). Patton owned a car, several guitars, always wore suits and was able to support his family financially. His fame and popularity was not limited to a black audience, his name was also well known among the white population, occasionally he played with white musicians and performed in front of white audiences, in the last years of his life they made up the majority of his audience.

Despite his success, however, his social status was low. Blues musicians were generally considered sinful by the very religious, "decent" majority of the Afro-American population because of their music, but also their way of life. The deep roots of belief in the population made this idea and its consequence, an afterlife in hell, a reality for the musicians themselves, which brought them into conflict with their own existence over and over again. For example, Palmer reports that Patton regularly withdrew from music and his "vicious" lifestyle, studied the Bible and wanted to take up the profession of preacher, but these resolutions only lasted for a short time.

plant

Patton's surviving solo work consists of a little over fifty pieces in almost sixty takes , which were created in four recording sessions between 1929 and 1934, just over forty pieces of which, the equivalent of a good three LPs, were recorded within just one year, 1929/1930. No blues musician before him has left such an extensive oeuvre. Patton also accompanied other musicians on their recordings, this part of his work also includes 10 to 20 pieces.

However, his repertoire was considerably larger and included (unusually) not only blues pieces, but also ragtimes, religious songs, folk pieces of white and black origins and popular music of the time, so Patton stood in the tradition of the so-called songsters of the turn of the century. Apart from religious pieces, however, this material has hardly been recorded by him and is therefore beyond further investigation.

All recordings that have survived have remained unaffected by creative interventions by the record companies. This was mainly due to the basic lack of understanding of the white employees of the record companies about the blues, which were perceived as primitive, as a rule, what the musician offered and hoped for success was simply recorded, published and sold, a targeted market strategy did not exist. The creative control was entirely up to the artist himself, which allows today's listener to get an almost undisguised look at Patton's work.

It should be noted, however, that the recordings received only ever show a section of the respective piece. The running time of the recordings at that time was limited to three minutes, so that longer pieces had to be split into two parts, there was hardly any room for longer solos or improvisations, and the up to thirty minutes long, highly repetitive passages that he presented live remained undocumented.

Influences

Little can be said about the influences on Patton's work, as he was stylistically established well before 1910, making him one of the earliest ever recorded blues artists, and comparisons with previous generations of musicians are hardly possible. It is very likely that his most important teachers, Henry Sloan and Earl Harris, influenced his playing, nothing is known about other influences from his early days. However, the rhythm and percussive style of playing, especially in his early pieces, shows many similarities to the ostinatian two-stroke pow wow music of the American Indians, with which he was most likely familiar from childhood through his Cherokee grandmother. It is known that with the advent of the first blues records from 1923/1924 he followed the market very closely and oriented himself towards successful pieces when composing new ones. B. Ma Rainey's Booze and Blues from 1924 as Tom Rushen Blues , he used the text of Ardelle Bragg's Bird Nest Blues in a modified form in Bird Nest Bound and used the Cryin 'Blues of Hound Head Henry as the basis for his Poor Me , as well as Sittin 'On Top Of The World the Mississippi Sheiks was the template for his Some Summer Day . His admiration, probably also because of his considerable success, went to the extremely successful pioneer of the country blues on record, Blind Lemon Jefferson.

Texts

In general, Patton's lyrics are considered the weakest element of his work. John Fahey described his texts as often characterized by " disconnection, incoherence, and apparent 'irrationality" , stated "stanzaic disjunction" , and summed up that in "Various unrelated portions of the universe are described at random" to them, however, also notes that such lyrical incoherence was a typical feature of the country blues itself. David Evans attributes this to the fact that Patton's texts (like his pieces as a whole) were not fixed in themselves, but were spontaneously improvised during the game using a few key lines, mostly of traditional origin and a basic idea in terms of content.

There are two main focuses in Patton's texts: In a large part the life of Patton is reflected, in some cases this goes so far that the texts have a downright autobiographical character. They are individualistic, closely tied to everyday experiences, offered the contemporary listener the opportunity to identify and are valuable contemporary documents of black everyday history from today's perspective. In these texts, Patton also transcended the thematic narrowing to love and the blues in the sense of an emotional constitution, which is often found in the blues. Although these topoi can of course also be found, Patton also addresses traveling, death or nature. However, the lyrics always maintain the character of light music, allusions to social grievances are extremely rare and are always limited to Patton's personal experiences, socially critical texts, such as criticism of racism, are completely absent.

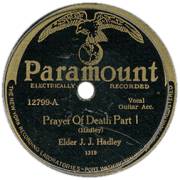

Another focus is on pieces that express Patton's deep religiosity, such as I'm Goin Home , Jesus Is A Dying Bed-Maker , Lord I'm Discouraged and especially the double-sided published under the pseudonym Elder JJ Hadley for reasons of credibility Prayer Of Death . The religious pieces only make up around a quarter to a third of his work, but many of the secular pieces also contain religious elements, from brief allusions to entire stanzas.

His singing style meant that the lyrics were often only understandable in fragments, even for contemporaries. To this day, many of the texts of his pieces are not fully understood or are interpreted differently, this is reinforced by the poor quality of the recordings received (which is not only due to the wear and tear of the decades, the Paramount company also used a very inferior material for pressing Plates).

music

Patton only played in the open tuning G ( Spanish ) or the standard tuning, according to his recordings , only one track in the open tuning D is known ( Spoonful Blues ). His guitar style was extremely percussive, during performances he occasionally used the body of the guitar over long periods as a pure percussion instrument. His bottleneck playing , which can be heard on around a third of his recordings, established this style as an integral part of the Delta Blues repertoire. Patton was a thoroughly virtuoso guitarist, but his resources were limited to what was necessary for his repertoire. He mastered the so-called fingerpicking excellently, but could hardly play chords; he was also unable to read music. Occasionally he let his guitar "speak" (heard clearly in the chorus of "A Spoonful Blues" , where he lets his guitar sing spoonful instead of his voice ). His pace was so fast that even a tech- savvy sideman like Willie Brown would occasionally complain about it. However, he did not master any other instruments; before 1916 he had tried unsuccessfully to learn to play the violin.

He sang Patton in a hoarse, growling, but surprisingly voluminous baritone voice that spanned over an octave (audible in pony blues ) and that was said to carry 500 yards without amplification . Sleepy John Estes called her "the loudest voice I've ever heard" and David Edwards said of her that she broke them country houses down . Often syllables were drawn out or extremely short pauses inserted into the lines in order to either adapt them to the meter or to achieve unusual rhythmic effects.

As he played, he rhythmically stamped his feet on the wood of the floor, putting the full weight of his legs into the steps, reinforced by metal nails under his shoes. According to Richard Harney , he achieved a volume “as if five or six people were stamping” ( “like it's five or six people in there stompin '” ). As was common in the early days of the blues, he sometimes played a figure on the guitar for well over half an hour in order to achieve a hypnotic effect (a method that is reminiscent of African music and Indian Pow Wow music as well as modern music genres such as Techno ).

Volume was an essential factor for success, as his audience could consist of several hundred people and the juke joints were already at a high volume level, so a musician was forced to assert himself by means of his volume.

Live presentation

Noteworthy was Patton's showmanship, which he practiced excessively and occasionally caused irritation among listeners. While he was sitting on a chair (as was customary at the time), he hit the strings and the body of the guitar with his fists and hands, threw them in the air and caught them - while his companion kept the beat - in time to get back in, played them behind his Head, between the knees, under the legs or on the back. These deposits were traditionally to be found in minstrel shows as early as the 19th century and were actually considered obsolete by 1910. As an entertainer, Patton was also prepared to make musical sacrifices to this show, an anecdote handed down by John Fahey describes this very vividly: when he played Patton records in 1965, which had heard Patton play countless times and was even present at recording sessions, he was surprised by the quality of his game: “I didn't know that he could play so well.” ( “I never knew he could play that good.” ). The experience here had overlaid what had been heard.

From around 1926 on, Patton was often accompanied by Willie Brown, who, however, moved to Son House in 1929. After that, Patton mostly played solo, but was occasionally accompanied by Henry Sims on the fiddle.

reception

Contemporary reception

Patton was the most influential artist at the wedding of the Delta Blues, his students, admirers and companions included numerous important blues musicians, as well as a handful of Patton imitators who played mainly in regions where Patton himself rarely or never performed. Howlin 'Wolf, who was inspired by Patton's performance to play the blues himself, had guitar lessons with him, performed as a Patton imitator in the early 1930s and later still followed him vocally. Son House owed his first recordings to Patton; Bukka White said that as a child, his goal was "to come to be a famous man, like Charley Patton" . Willie Brown, who was friends with him and was his most important sideman from 1915 until his death , also learned a lot from him. He also influenced Tommy Johnson (who covered two of his pieces), Big Joe Williams and Roebuck "Pops" Staples as well as many blues musicians of the second line, such as B. Booker Miller , Kid Bailey , Buddy Boy Hawkins or David Honeyboy Edwards . The young Robert Johnson, who gave Johnny Shines to Patton as inspiration and started as a Patton impersonator, also stayed a lot around Patton around 1930, but received no approval because he was considered a passable blues harp player but a bad guitarist (a judgment that was however revised by Brown and House after Johnson's famous year of traveling). Patton's fame made Dockery Plantation a meeting place for all these musicians and so famous as the "birthplace of the Delta Blues".

But not only was Patton's influence on other musicians unparalleled in his time in the blues, his status with the audience was also unique. Before Patton, musicians in the Delta were semi-anonymous service providers with no special, individual status, they played - similar to today's solo entertainers - without being asked for their name. Patton, on the other hand, built a reputation for himself during his career that (as numerous reports from contemporaries testify) meant that audiences came to an event just for him.

In 1947 (and without mentioning Patton as the author), the country musician Hank Williams recorded Patton's piece Going to Move to Alabama under the title Move It on Over and thus achieved its first national success, Williams' play reached number 4 in Billboard Country Singles charts, he is commonly credited with having a strong influence on emerging rock'n'roll.

Rediscovery

As with almost all country and delta blues performers, Patton's work was only rediscovered late. Despite the publication of two compilations in the 1960s, his extraordinary influence on subsequent blues artists in particular was little appreciated for a long time. Above all, the long shadow of the "myth" Robert Johnson, who had a disproportionately higher rank in the reception of the white audience, blocked the view of Patton for a long time. Although it was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame when it was founded in 1980 , its importance was only increasingly recognized outside of specialist circles with the appearance of the first editions of the work in the early 1990s. In 2001, after several years of work , the American small label Revenant Records published a comprehensive complete edition of all of its recordings, including previously unpublished pieces and two extensive volumes of material on life and work. The critically acclaimed edition ( “It truly is the last word, and one of the most impressively packaged box sets in all of popular music.”) “That is truly the last word and one of the most impressively packed box sets in all popular music. ”) was awarded three Grammys in 2003 ( Best Album Notes, Best Boxed Or Special Limited Edition Package, Best Historical Album ) and was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2006 as a Classics of Blues Recording (album) . Rare original 78s from Patton are now sold at auctions for prices between $ 15,000 and $ 20,000. Patton's 1929 song "Pony Blues" was entered into the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress by the United States' National Recording Preservation Board in 2006

Bob Dylan said of Patton, "If I was making records for my own enjoyment, I would only record Charley Patton songs" and in 2001 he dedicated the track "High Water (For Charlie Patton)" to him . Even Chris Rea appeals to him. In an interview he described his key experience “... that's when I heard Charley Patton for the first time. It was kind of a spiritual experience for me. I was absolutely caught up in the way he sang, played, and conveyed that particular emotion. I hadn't played guitar until then [...] This episode changed my entire life! ”. The American comic book writer and blues connoisseur Robert Crumb honored Patton in 1984 with a biography in the form of a comic, based on the biography of Wardlow and Calt.

Despite his self-image as an entertainer and his focus on success (regardless of the occasional critical view of Patton's artistic seriousness) no scholarly author denies his enormous importance for the blues. Fahey praised him with the words "for me he was the most exciting guitarist and blues singer I had ever heard" ( "to me he was the most exciting guitar player and blues singer ever heard" ) and Gayle Dean Wardlow referred to him As “an innovator, the first great delta bluesman” ( “an innovator, the first great delta bluesman” ), however, the question is whether there was a tradition of (delta) blues before Patton, from which Patton's style emerged organically developed (Evans, Fahey, Palmer) or whether Patton actually invented this style (Wardlow, Calt). The problem is that there are no records from the generation of musicians before Patton that could validly decide this question.

The enormous importance of Patton was recognized more and more in the early 21st century, so musicologist John Troutman summarized in 2017:

“Blues connoisseurs are far from agreeing on everything, but if you could lock them all up in one room and they should agree on who was the most important blues guitarist, singer and songwriter, simply the greatest in the early 20th century , everyone would probably say: Charley Patton. "

research

Research on Patton suffers - typical of the pre-war blues - from the fact that there are virtually no written sources about him and just as few personal testimonies. Almost everything that is known about Patton comes either from his work (where interpretations are always confronted with the possibility of the literary self ) or from the statements of people around him, who were usually only interviewed in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s Reliability is therefore often low. A striking example of such misleading oral testimony are the statements by Son House, which shaped research for a long time and in which House painted a very negative image of Patton, both personally and musically.

During its incipient rediscovery in the 1960s, research focused primarily on Patton's biography. Its pioneer was Bernard Klatzko , who in 1964 for the second part of the fundamental compilation The Immortal Charlie Patton on a trip to the Mississippi Delta, during which he interviewed friends and relatives about Patton, collected the first biographical information about Patton.

In the same year Son House was rediscovered, in an interview he portrayed Patton as contentious, selfish, greedy, alcoholic and stingy, negligent towards his music, as an illiterate and philanderer. In an article accompanying the interview and in later publications, the authors Gayle Dean Wardlow and Stephen Calt deepened the image of Patton as a "degenerate sociopath", but revised it in their detailed biography in 1988 and suspected that Son House was increasingly a caricature motivated by resentment Designed by Patton.

It was not until the musician, musicologist and blues lover John Fahey turned to the study of text and music in Patton's work in his master’s thesis in 1970, in addition to a brief biographical description. He drew Patton as a pure entertainer who lacked depth and sensitivity in terms of content, a judgment that he later corrected in his text accompanying the 2001 Complete Edition. For the biographical data he made extensive use of existing material, but supplemented it with his own research (inter alia, interviews with Bertha Lee and Sam Chatmon).

Robert Palmer corrected the biographical picture of Patton in his 1981 book Deep Blues , which (concerning Patton) had previously disregarded interviews with Joe Rice Dockery (then owner of Dockery Plantation ), Hayes McMullen , Howlin 'Wolf and Roebuck Staples. in which he placed the incriminated character traits in the social context of the Mississippi Delta at the beginning of the century and made it clear that promiscuity, violence and alcohol were an integral part of the juke joint subculture, so Patton's behavior was by no means out of the role.

In 1984, on the fiftieth anniversary of Patton's death, an international symposium took place in Liège under the title The Voice of the Delta - Charley Patton And the Mississippi Blues Traditions . in the field of black American popular music "( " un des plus grands artistes [...] dans le domaine de la musique populaire négro-americaine " ).

In the symposium volume, David Evans corrected in his biographical essay "The Conscience Of The Delta" - in his opinion mainly based on the statements of Son House - heavily distorted personal image of Patton and supplemented it with a lot of information, attesting to his artistic seriousness and sensitivity. The essay was slightly revised and updated in 2001, republished as part of the work edition and awarded a Grammy.

Pictorial evidence

For a long time Patton was only known to have drawn or roughly rastered representations from advertisements. All of these images were obviously always based on the same image, which was only changed with graphic means. For example, the image for the Masked Marvel campaign shows a blindfolded Patton , the image for the Spoonful Blues shows a restaurant scene in which Patton is sitting at the table, the ad for the 34 Blues shows a man sitting on the chair with his legs crossed was holding a guitar lying on his lap. It was not until 2003 that the original photo of all these drawings was discovered by John Tefteller, owner of one of the largest private blues collections in the world, who still owns the picture to this day. Patton had this picture taken by himself and intended to use it on announcements for performances, a very professional and at the time absolutely unusual practice. Another photo of Patton in 1908 as a young man with a mustache shows little agreement and was not re-published after its first publication in the monograph by Calt and Wardlow.

Music samples

Discography

Original 78s

This is a complete listing of all of Charley Patton's original recordings in chronological order. Due to the sensitive shellac , only a few specimens have survived; the American collector and expert John Tefteller estimates the total number of preserved pieces to be no more than 100.

| title | Catalog number | publication | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paramount | |||

| Pony Blues / Banty Rooster Blues | Paramount 12792 | July 1929 | |

| Prayer of Death Pt.1 / Prayer of Death Pt. 2 | Paramount 12799 | Pseudonym as Elder J. Hadley | |

| Screamin 'and Hollerin' the Blues / Mississippi Bo Weavil Blues | Paramount 12805 | temporarily pseudonym as The Masked Marvel | |

| Down the Dirt Road Blues / It Won't Be Long | Paramount 12854 | ||

| A Spoonful Blues / Shake It and Break It But Don't Let It Fall Mama | Paramount 12869 | ||

| Pea Vine Blues / Tom Rushen Blues | Paramount 12877 | ||

| Lord I'm Discouraged / I'm Going Home | Paramount 12883 | ||

| High Water Everywhere Pt. 1 / High Water Everywhere Pt. 2 | Paramount 12909 | April 1930 | |

| Rattlesnake Blues / Running Wild Blues | Paramount 12924 | ||

| Magnolia Blues / Mean Black Cat Blues | Paramount 12943 | July 1930 | |

| Mean Black Moan / Heart Like Railroad Steel | Paramount 12953 | August 1930 | |

| Green River Blues / Elder Greene Blues | Paramount 12972 | September 1930 | |

| Jesus Is a Dying-Bed Maker / I Shall Not Be Moved | Paramount 12986 | October 1930 | |

| Hammer Blues / When Your Way Gets Dark | Paramount 12988 | November 1930 | |

| Moon Going Down / Going to Move to Alabama | Paramount 13014 | December 1930 | |

| Some Happy Day / You're Gonna Need Somebody When You Die | Paramount 13031 | ||

| Circle Round the Moon / Devil Sent the Rain Blues | Paramount 13040 | Late 1930 / early 1931 | |

| Dry Well Blues / Bird Nest Bound | Paramount 13070 | Spring 1931 | |

| Some Summer Day Pt. 1 / Jim Lee Blues Pt. 1 | Paramount 13080 | Spring / summer 1931 | |

| Frankie and Albert / Some These Days I'll Be Gone | Paramount 13110 | Early 1932 | |

| Joe Kirby / Jim Lee Blues Pt. 2 | Paramount 13133 | Early 1932 | |

| Vocalion | |||

| 34 Blues / Poor Me | Vocalion 02651 | ||

| High Sheriff Blues / Stone Pony Blues | Vocalion 02680 | April 15, 1934 | |

| Love My Stuff / Jersey Bull Blues | Vocalion 02782 | September 1, 1934 | |

| Oh Death / Troubled 'Bout My Mother | Vocalion 02904 | with Bertha Lee | |

| Hang It on the Wall / Revenue Wall Blues | Vocalion 02931 | April 15, 1935 | |

Work edition

- Screamin 'and Hollerin' the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton , Revenant Records No. 212, 2001, (seven CDs with all recordings in all versions of Patton as a soloist and accompanying musician, the recordings of the artists he has arranged and two volumes of material)

Remarks

- ↑ This does not mean the mouth region of the Mississippi south of Baton Rouge , Louisiana , but a region on the Mississippi in the state of the same name, see → Lower Mississippi Delta Region # Mississippi Delta, Mississippi

swell

- Stephen Calt, Gayle Wardlow : King of the Delta Blues. The Life and Music of Charlie Patton . Rock Chapel, Newton NJ 1988, ISBN 0-9618610-0-2 .

- David Evans : Charley Patton Biography . In the volume accompanying the 2001 edition, online ( Memento from January 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- John Fahey : Charley Patton . Studio Vista, London 1970, ISBN 0-289-70030-2 , ( Blues paperbacks ).

- Robert Palmer : Deep Blues . Penguin Books, New York NY 1995, ISBN 0-14-006223-8 .

- Robert Sacré (Ed.): The Voice of the Delta. Charley Patton and the Mississippi Blues Traditions. Influences and Comparisons. At International Symposium . Presses Universitaires de Liège, Liège 1987, ISBN 2-87014-163-7 .

- Robert Santelli: The Big Book of Blues. A Biographical Encyclopedia . Penguin, New York NY et al. a. 1993, ISBN 0-14-015939-8 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Robert Santelli: The Big Book Of Blues , pp. 323-324

- ↑ a b c d e f g David Evans : Charley Patton Biography . In the volume accompanying the 2001 edition of the work, paramountshome.org ( Memento from January 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Stephen Calt & Gayle Wardlow, King of the Delta Blues , p. 96

- ↑ John Fahey, Charley Patton , p. 20

- ↑ Pat Howse, Jimmy Phillips: Godfather Of Delta Blues - HC Speir - An Interview with Gayle Dean Wardlow , in: Peavey Monitor, 1995, pp. 34-44. Online: Archive link ( Memento of the original from August 5, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ David Luhrssen, Blues in Wisconsin: The Paramount Records Story. , in: Wisconsin Academy Review, 45 (Winter 1998–1999), p. 21

- ↑ digitaljournalist.org A photo of Rosetta from 1996.

- ↑ Stephen Calt & Gayle Wardlow, King of the Delta Blues , 195

- ^ Robert Palmer: Deep Blues. P. 52.

- ↑ Anna Hoefnagels, “Northern Style Powwow Music: Musical Features and Meanings,” Canadian Journal for Traditional Music / Revue de musique folklorique canadienne vol. 31 (2004): 10-23.

- ^ John Fahey, Charley Patton , p. 60

- ^ John Fahey, Charley Patton , p. 62

- ^ John Fahey, Charley Patton , p. 65

- ^ John Fahey, Charley Patton , p. 23

- ^ John Fahey, Charley Patton , p. 29

- ↑ a b John Fahey, Charley Patton , pp. 36-37

- ^ Stephen Calt & Gayle Wardlow, King of the Delta Blues , p. 164

- ↑ Stephen Calt & Gayle Wardlow, King of the Delta Blues , p. 22

- ↑ Stephen Calt & Gayle Wardlow, King of the Delta Blues , p. 21

- ↑ Stephen Calt & Gayle Wardlow, King of the Delta Blues , p. 23

- ↑ John Fahey, Charley Patton , p. 31

- ↑ Tony Burke, Norman Darwen: "Who May Your Regular Be?", Interview with David "Honeyboy" Edwards, in: Blues & Rhythm: The Gospel Truth , 156, pp. 4-8

- ↑ See the list under: Archive link ( Memento of the original from March 5, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Richie Unterberger, AllMusicGuide [1]

- ↑ a b Amanda Petrusich: They've Got Those Old, Hard-to-Find Blues . In: The New York Times, July 12, 2009, p. AR15 / New York Edition, July 8, 2009; Retrieved March 18, 2010

- ↑ 2003 National Recording Registry Choices

- ↑ Dietmar Hoscher, Blues Talk - Episode 27: Roots without Borders: Chris Rea, Otis Taylor, Willy DeVille . In: Concerto , No. 1, February 2003, online: Archived copy ( memento of the original from January 23, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Robert Crumb: R. Crumb Draws the Blues , ISBN 0-86719-401-4

- ↑ Stefan Grossmann, Interview with John Fahey, online: Archive link ( Memento of the original from September 2, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Patrick Howse: Blues Researcher Gayle Dean Waldlow Talks About Delta Blues and the Robert Johnson Mystery. , in: Peavey Monitor 10, # 3 (1991): 30-39. Online: Archive link ( Memento of the original dated November 15, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ John Troutman in: Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World , Documentation, 2017, Director: Catherine Bainbridge, Alfonso Maiorana, 26:04 - 26:55

- ↑ David Evans on the Patton picture of Wardlow and Calt, in: David Evans, Charley Patton Biography , companion volume for the 2001 edition, online: Archivlink ( Memento of the original from February 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and still Not checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Stephen Calt & Gayle Wardlow, King of the Delta Blues , p. 19

- ^ Robert Sacre, Avant Propos , in: Robert Sacré (Ed.), The Voice of the Delta - Charley Patton and the Mississippi Blues Traditions , p.9

- ↑ David Evans: The Conscience Of The Delta , in: Robert Sacré (ed.), The Voice of the Delta - Charley Patton and the Mississippi Blues Traditions , pp. 111-214

- ↑ Figure see here

Web links

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Patton, Charley |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Patton, Charlie |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American blues musician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1891 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | near Bolton , Mississippi, USA |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 28, 1934 |

| Place of death | Indianola , Mississippi |