De coniuratione Catilinae

De coniuratione Catilinae or Bellum Catilinae ( Latin for On the Conspiracy of Catiline or The War of Catiline ) is a monograph by the Roman historian Sallust . It comprises 61 chapters and was written around the year 41 BC. In it, Sallust describes the conspiracy of Lucius Sergius Catilina , who began in 63 BC. BC tried to usurp power in the Roman Republic by means of a coup , which was thwarted by the consul Marcus Tullius Cicero . In addition to his speeches, this first work by Sallust is the most important source about these events, as well as in the original language since the Middle Ages "school material" of Latin lessons.

content

In the Proömium , which comprises the first four chapters of his work, Sallust describes the gloria , fame , as the meaning of human existence . Sallust looks back on his own failed career as a politician and justifies his now intellectual activity as a historian in comparison to the vita activa of a politician or military leader. In the fifth chapter follows a characteristic of his protagonist, who is certified as having good dispositions, but who is demonized in his moral depravity.

A first digression follows , in which Sallust describes a general decline in morality as the cause of the crisis in the Roman Republic . Instead of virtus , the virtue or bravery that made Rome great in the past centuries, since the end of the Punic Wars more and more avaritia and luxuria have spread, greed and waste . Catiline is portrayed as the ideal representative of these two vices .

The actual action only begins with the prehistory of Catiline's activities in chapters 17 to 22. After describing the so-called first Catilinarian conspiracy of 65, Catiline gave a speech to his followers. Sallust also reproduces the horror tale that Catiline gave his followers a mixture of wine and human blood to confirm their oath of loyalty. In chapters 23 to 24 he tells how Fulvia, the mistress of Quintus Curius , betrayed the conspiracy, which contributed to Catiline failing to be elected consul for 62. Chapter 25 is then an excursus on Sempronia , which is described as the female counterpart to Catiline. In the next chapters a description of the concrete preparations for the uprising follows, which is interrupted in chapters 36 to 39 by a further excursus in which Sallust is based on the pathology of the Polis of Thucydides (Peloponnesian War, 3.82–84). Here Sallust complements his moral analysis of the crisis with social analyzes of the supporters of Catiline and with a sharp criticism of the two parties of the late Roman Republic: The optimates are accused of using only false phrases to fight for their own power, but also the popular ones , He does not spare Sallust himself as a follower of Caesar : They are portrayed as irresponsible demagogues who use populist slogans to incite the people against the traditional rule of the Senate .

The plot continues in chapters 39 to 49: the conspiracy is exposed through the betrayal of the Allobrogians , Gauls with whom Catiline hoped to ally; the followers of Catiline, who himself had already left the city, are being interrogated. This is followed in Chapters 50 to 55 with a detailed description of the Senate deliberations on the question of how to proceed with them. While Caesar pleads for the conspirators to be punished with confiscation of their property and imprisonment in the country towns of Italy, Marcus Porcius Cato the Younger wins with his motion to execute them. In the last six chapters of the work, the military smashing of the conspiracy in the Battle of Pistoria is told.

research

Intention and tendency

For a long time, Sallust research was under the impression of Theodor Mommsen's judgment , according to which the work was a “political tendency writing ” with which the author tried to cleanse the image of his former mentor Caesar “from the blackest stain that adhered to it ", Namely on the suspicion of being involved in the Catiline conspiracy. At the same time, Sallust wanted to denounce the nobility:

"The fact that the skilled writer lets the apologetic and accusatory character of these of his books recede does not prove that they are not, but that they are good party writings ."

Since the work of Friedrich Klingner and Hans Drexler in 1928, however, the interpretation has prevailed that Sallust was not a party man, but a serious history thinker who was concerned about the traditional values of the res publica , the mos maiorum . Accordingly, the real theme of the Bellum Catilinae was less the preparation and exposure of the historically insignificant machinations of Catiline and his followers than the crisis of the Roman Republic and the civil wars of Sallust's time. Catiline is drawn anachronistically as its anticipated symbol . The author already suggests this at the end of the Proömium, where he writes that he has chosen his subject sceleris atque periculi novitate because of the novelty of the dangerous crime - this implies that coups d' états , coups and civil wars are no longer novel in the following period or were rare.

Sallust found the division of the Roman nobility into optimates and populars, which finally escalated in the civil wars, as a tragedy . This is shown not only in the party excursion, which is placed almost exactly in the middle of the book, which underlines its importance for the overall work, but also in the great speech duel between Caesar and Cato, the two prominent opponents in the civil war of 49 to 46 Sallust compares them in detail in Chapter 54, but this does not do justice to their importance at the time: Compared to the consul Cicero, whose role Sallust takes more into the background, Caesar and Cato, as former aedile and former quaestor, were certainly not among the most important politicians of the year 63 BC In a detailed comparison, Sallust evaluates both equally positively, but complementary in their virtues. The references to the present become particularly clear in the description of the battlefield of Pistoria, with which the work closes. Here Sallust does not deny the arch villain Catilina respect for his bravery - Catilina's corpse is said to have been found far from his own in the midst of slain enemies - Sallust also paints the whole horror of a civil war:

“Multi autem, qui e castris visundi aut spoliandi gratia processerant, volventes hostilia cadavera amicum alii, pars hospitem aut cognatum reperiebant; fuere item, qui inimicos suos cognoscerent. ita varie per omnem exercitum laetitia, maeror, luctus atque gaudia agitabantur.

But many who visited the battlefield from the camp out of curiosity or the desire to plunder found, when they turned the corpses of the enemy, partly a friend, partly a host or relative. But some also recognized their personal enemies. So there was joy and pain, lamentation and jubilation throughout the entire army in a colorful alternation. "

The ancient historian Ronald Syme, on the other hand, gives several arguments for the fact that a tendency can be discerned in Sallust's work : It is directed against the dictatorial rule of the second triumvirate , which was concluded in November 43 shortly before the writing of De coniuratione Catilinae , and above all against Caesar's heir Octavian , who called himself Gaius Iulius Caesar after his adoptive father. As evidence, Syme cites the comparison of Caesar with Cato, in which he is portrayed more positively, but above all the role that Sulla plays in the text. In the years 82 to 79, after a first civil war, he had established a dictatorship and, like the triumvirs in Sallust's presence, proclaimed thousands of political opponents outlawed and had them killed. Syme reads the numerous and always negative mentions of the dead dictator (e.g. in Chapters 5, 11, 16, 21, 28 and 37) as a hidden criticism of his present, which is also marked by atrocities and civil wars.

As the deeper causes of these civil wars, Sallust does not primarily analyze the increasing social tensions within society, the overstretching of the empire or the relatively new institution of the army clientele , with which modern historiography explains the failure of the Roman Republic. In a way that seems “naive” today, he explains the crisis more morally : it was caused by a disintegration of the concordia , the unity that had to rule within the community. The very existence of two parties struggling for leadership in the state is already pernicious for him; he can only explain it with a decline in general morals. He attributes this decadence to the blind rage of fate (chap. 10, 1: saevire fortuna et miscere omnia coepit ). Since resistance against fate is impossible, the author does not offer any possible solutions for the crisis of the Roman Republic. In this sense, his view of history ultimately remains fatalistic and thus unhistorical.

Historical reliability

Sallust evidently had access to more sources than Cicero and is therefore able to offer information that is otherwise not available. For example, in chapters 33 and 35 he quotes letters from Catiline and his officer Manlius , which Cicero could not yet have available to him when he was writing his speeches, since they were only accessible after the conspiracy had been discovered. These documents, which researchers consider to be largely genuine, allow conclusions to be drawn about the socio-historical background of the uprising and about Catilina's personal motivation, who felt his dignitas , his personal dignity, offended by the repeated failures in the elections .

On the other hand, there are several, in some cases serious, historical errors or falsifications , which go well beyond the use of fictional speeches and documents customary in ancient historiography: In Chapter 17, the beginning of the conspiracy is postponed by a full year to the year 64. The so-called first Catilinarian conspiracy, about which Sallust reports in chapter 18, is now unanimously held by scholars to be an afterthought. Also incorrectly dated is the Senatus consultum ultimum , which Sallust puts on November 8th in Chapter 29 with Cicero's first speech against Catiline - in truth the Senate had already declared a state of emergency on October 21st.

The classical philologist Ludwig Bieler explains this obvious historical unreliability in Sallust's monograph with his a priori view of history and his deductive working method:

“Sallust approaches his subject as a dogmatist , with a philosophy of history that has grown together from life and reading , which he repeatedly sees confirmed in the special events. He has no real or immediate interest in the facts as such. "

Language and style

The shortcomings in terms of historical reliability in De coniuratione Catilinae are often explained by the fact that it is at least as much a linguistic work of art as it is a work of history. This high artistic desire can be recognized in the novel -like , rondo-like composition of the work around the three central characters Catilina - Caesar - Cato. Above all, however, Sallust's style is praised, which he developed for the first time in De coniuratione Catilinae . The radical style will that permeates the entire work down to the linguistic details is compared by the classical philologist Karl Büchner with that of a “virtuoso composer who knows what he is playing with every note and who must therefore be heard accordingly. “In Catiline it shows itself in inconsistencies , a deliberate brevity of expression, which is often pointed to concise sentences , but which is opposed to asyndetically lined up, abundant expressions elsewhere , a tendency towards rare, sought-after vocabulary and archaic forms. The classical philologist Will Richter called this style mannerism , insofar as Sallust wanted to consciously express things anomalously, to prefer the artificial and sought-after to the obvious and natural, in order to surprise and astonish his readers again and again.

For this mannerism in the language of De coniuratione Catilinae different motives are given by research, which need not be mutually exclusive: On the one hand, Sallust followed the language of his historiographical predecessors, namely the older Cato and Lucius Cornelius Sisenna , whose history he later worked on linked with his histories . On the other hand, it is argued that the reason is the linguistic orientation to Thucydides , who as one of the oldest of the Attic writers wrote a comparatively archaic Greek. Thirdly, it is stated that Sallust had internal reasons for his mannerism: in his deliberately anti-classical style, it was important to him to distinguish himself linguistically from his present, in which the Ciceronian model of the balanced, far-reaching period was the recognized style ideal . According to this interpretation, in De coniuratione Catilinae, the content of the philosophy of history and the linguistic form are remarkably mutually dependent, which is why Ludwig Bieler judges that Sallust's art of historical representation deserves “undivided admiration”.

reception

The small monograph already met with great admiration in antiquity, although initially less as a work of history than for its rounded composition and bold style. The rhetorician Quintilian even put its author on the same level as Thucydides (Institutio oratoria II / 18; X / 101) and regularly cites examples from De coniuratione Catilinae , although it did not correspond to the stylistic ideal of Cicero that he propagated. The historian Tacitus oriented himself strongly to Sallust's work and adopted both his style and the pessimistic view of history. In his Annales he praises Sallust as "rerum Romanarum florentissimus auctor", as "the most important Roman historian" (III, 30).

The church father Augustine referred to Sallust not only as "lectissimus pensator verborum", i. H. “Extremely exemplary weighing of his words” ( De beata vita 31), but even as “nobilitatae veritatis historicus”, as “historians of recognized love for truth” ( De civitate Dei I, 5). He often quoted it in his great apologetic work De civitate Dei from it (e.g. II, 17f.21; III, 2.10.14) because he wanted to prove that pagan Rome had been desolate and corrupted until itself its inhabitants converted to Christianity.

De coniuratione Catilinae was taught in schools as early as the Middle Ages . The appreciation of the script, which was so highly praised by Augustine, can also be measured by the fact that more than twenty manuscripts have survived. The first printed edition appeared in Venice as early as 1470. Shortly afterwards, the humanist Angelo Poliziano wrote his Pactianae coniurationis commentarium (report on the Pazzi conspiracy ), which was based in style and statement closely on Sallust's De coniuratione Catilinae . In 1513 the first German translation was printed in Landshut under the title: "The highly fluffy Latin historian Sallustii got two histories, namely of Catilinan and Jugurthen".

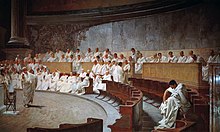

Since then, Catiline and Sallust's text, on which the idea of him is largely based, has become an integral part of Western intellectual life. De coniuratione Catilinae is an integral part of Latin lessons , the fresco by the otherwise insignificant Italian history painter Cesare Maccari from 1888, which in the drawing of the physiognomy of Catiline clearly refers to Sallust's work, is depicted in many school books and thus shapes the idea of how it is to this day received in a Senate meeting. Bismarck's coined term “Catilinarian existence” for someone who has nothing to lose and therefore dares everything has become a popular phrase . Friedrich Nietzsche confessed that his own sense of style and epigrammatic brevity was awakened "instantly when he met Sallust", and in Bertolt Brecht's 1949 novel The Business of Mr. Julius Caesar there are numerous traces of a Sallust reading: Brecht took over for example, almost literally whole passages about the description of the battle of Pistoria from Sallust's work.

Text editions and translations

- C. Sallustius Crispus: Catilina, Iugurtha, Historiarum Fragmenta Selecta; Appendix Sallustiana . Edited by LD Reynolds , Oxford 1991, ISBN 978-0-19-814667-4 .

- C. Sallustius Crispus: De Catilinae coniuratione . Commented by Karl Vretska , 2 vol., Heidelberg 1976.

- C. Sallustius Crispus: De coniuratione Catilinae / The Conspiracy of Catilina . Latin / German. Translated and edited by Karl Büchner , Reclam, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-15-009428-3 .

- C. Sallustius Crispus: The Conspiracy of Catiline . Latin-German. Edited, translated and commented by Josef Lindauer . 3. Edition. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-05-005751-4 .

literature

- Carl Becker : Sallust , in: The rise and fall of the Roman world . Vol. I, 3rd edition. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York 1973, pp. 720–754.

- Viktor Pöschl (Ed.): Sallust . (= Paths of Research . Vol. 94). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1970.

- Ronald Syme : Sallust , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1995, ISBN 3-534-04355-3 (The English original edition was published in 1964).

- Klaus Bringmann : Sallust's handling of historical truth in his portrayal of the Catilinarian Conspiracy. In: Philologus 116 (1972), pp. 98-113.

- Gabriele Ledworuski: Historiographical contradictions in Sallust's monograph on the Catilinarian Conspiracy (= Studies on Classical Philology. Vol. 89). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1994, ISBN 3-631-47221-8 (also: Berlin, Freie Universität, dissertation, 1992).

- Yanick Maes: Sallust. E. Bellum Catilinarium. In: Christine Walde (Ed.): The reception of ancient literature. Kulturhistorisches Werklexikon (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 7). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2010, ISBN 978-3-476-02034-5 , Sp. 809-826.

Web links

- Full Latin text

- Latin text with German translation and abstract

- Thorsten Burkard: Current research: Sallust. A research report, in: Pegasus Online Journal IV / 1 (2004)

Remarks

- ↑ Theodor Mommsen: Roman History, Volume Three, Chapter 5 - The Party Struggle During Pompey's Absence (footnote) , 6th edition 1895, p. 195 ( online )

- ↑ Friedrich Klingner: About the introduction to the histories of Sallust , in Hermes 63 (1928), pp. 571-593; Hans Drexler: Sallust , in: New year books for science and youth education 4 (1928), pp. 390–399; both accessible today in: Viktor Pöschl (Ed.), Sallust. Ways of Research , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1970, pp. 1-44.

- ^ Karl Vretska : The structure of the Bellum Catilinae , in: Hermes 72 (1937); available today in: Viktor Pöschl (Ed.), Sallust. Ways of Research , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1970, pp. 95ff. That the Bellum Catilinae not only resembles a tragedy in terms of content, but also as it is structured in five acts, which u. a. Richard Reitzenstein asserted (the same, Hellenistic miracle stories , Leipzig 1906, pp. 84-89), has been disputed more recently, Karl Büchner , Sallust , Heidelberg 1960, pp. 246f.

- ^ Karl Christ: Crisis and Downfall of the Roman Republic , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1979, p. 264ff.

- ^ German translation by Egon Gottwein

- ^ Ronald Syme: Sallust , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1995, pp. 117–124.

- ↑ Thomas F. Scanlon: Spes Frustrata. A Reading of Sallust , Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1987, p. 63.

- ↑ Richard Mellein: De coniuratione Catilinae in: Kindler Literaturlexikon ., Vol 4, Kindler Verlag, Zurich 1965, p 2398th

- ^ Walter Wimmel : The temporal anticipations in Sallusts Catilina , in: Hermes 95 (1967), p. 192ff.

- ↑ Ronald Syme: Sallust , Darmstadt 1995, p. 88ff; R. Seager, The First Catilinarian Conspiracy , in: Historia 13 (1964), pp. 338-347.

- ↑ Ludwig Bieler: History of Roman Literature , 4th Edition, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York 1980, Part I, p. 137.

- ^ Ronald Syme: Sallust , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1995, p. 6.

- ^ Gaius Sallustius Crispus: De coniuratione Catilinae. The Conspiracy of Catiline, Latin and German , translated and edited by Karl Büchner, Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 1972, p. 119.

- ↑ Will Richter: The mannerism of Sallust and the language of Roman historiography , in: Rise and decline of the Roman world . Vol. I, 3. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York 1973, pp. 755-780.

- ^ A b Ludwig Bieler: History of Roman Literature , 4th Edition, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York 1980, Part I, p. 139.

- ↑ C. Sallusti Crispi Catilina, Iugurtha, Fragmenta ampliora post AW Ahlberg edidit. Alphonsus Kurfess , Teubner Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig 1981, p. XXXII; Rosamund McKitterick, The audience for Latin historiography in the early middle ages. Text transmission and manuscript dissemination , in: Anton Scharer and Georg Scheibelreiter (eds.), Historiography in the Early Middle Ages , R. Oldenbourg Verlag, Vienna and Munich, p. 100ff.

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche, Götzen-Dämmerung, in: Works in three volumes, ed. v. Karl Schlechta, Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1997, Vol. 2, p. 1027.

- ^ Hans Dahlke: Caesar with Brecht. A comparative consideration , Berlin / Weimar 1968, p. 136.