Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (* around 138 BC; † 78 BC ; briefly Sulla , sometimes also written Sylla or Silla) was a Roman politician, general and dictator in the late phase of the republic .

Corruption as well as conflicts over land distribution and civil rights had led the Roman Republic into a state of internal violence. In this crisis, Sulla rose to be an important commander. As quaestor of the general Gaius Marius , he ended the Yugurthin War and, after his successes in the war of allies, became consul of the year 88 BC. Elected. In the following years he urged Mithridates VI. back from Pontus . As a leading representative of the conservative aristocratic party ( Optimates ) he marched in the years 88 and 83 BC. On Rome to eliminate his popular opponents.

After the victory in the civil war, Sulla settled in 82 BC. Appoint dictator. On the basis of his unlimited competence legibus scribundis et rei publicae constituendae ("to give laws and to regulate the state") he carried out the first proscriptions of Roman history and had thousands of Roman nobles killed. His constitutional reforms were aimed at the sustainable restoration of Senate rule and the weakening of democratic institutions such as the people's tribunate . In 79 BC Sulla put down the dictatorship and withdrew into private life. His reign of terror could only briefly halt the civil war and the downfall of the old republic. Sulla's name is synonymous with cruelty and terror to this day.

Life until dictatorship

Early years

Sulla came from the patrician dynasty of the Cornelier . In contrast to the successful branches of the Scipions and Lentuli , since the second consulate was dressed by Publius Cornelius Rufinus in 277 BC No one from the branch of the Cornelier family, to which Sulla belonged, rose to the highest state office. Rufinus' son, who is said to have been the first to run the Cognomen Sulla , was flamen Dialis (priest of Jupiter ), which precluded a political and military career. Sulla's grandfather held the praetur in 186 BC. BC, while it is disputed whether his father, Lucius Cornelius, was also a praetor.

Sulla grew up with his brother Servius Cornelius and a sister. Since his mother died at an early age, Sulla was mostly under the care of a wet nurse . His father entered into another marriage to a wealthy woman. All that is known about him is that he left so little behind Sulla that he lived as a young man in a tenement house with freed slaves. At the age of fifteen Sulla received the toga virilis .

As a child and a young man, Sulla witnessed the Gracchian attempts at reform that would decisively shape his later political goals. The reason for the reforms were the changes that had taken place with the rural economy and the appropriation of the state - the so-called ager publicus . The ager publicus arose from the great conquests. Any Roman citizen was allowed to take possession of land if he paid a small usage fee. The small farmers were therefore ousted by the large landowners, who were able to appropriate more land. The two Gracches, Tiberius and Gaius Sempronius Gracchus , tried to implement an agrarian reform against the Senate in order to give the small farmers more land again. A family should have no more than 1,000 yokes of land. The tribune Tiberius Gracchus did not even submit a law to the Senate, but addressed the people's assembly immediately . The constitution was broken when Tiberius had a tribune of the people who interceded against the law removed. In order to raise money for new settlers, Tiberius confiscated the legacy of King Attalus of Pergamon, which had been bequeathed to the Romans , which represented a further breach of the constitution and an encroachment on the financial sovereignty of the Senate. When Tiberius, contrary to Roman tradition, wanted to apply for the tribunate again next year, there were tumults on election day. Tiberius Gracchus and his followers were slain, the bodies thrown into the Tiber.

When Gaius Gracchus resumed his brother's reform project a few years later, the Senate declared a state of emergency . For the first time, the military was used against its own citizenship. Gaius fled and let himself be killed by a slave in a hopeless situation.

Groupings analogous to the party formed, the Optimates , who stood up for the interests of the conservative nobilitas , mostly the patrician nobility, and above all worked to strengthen the Senate in the power play of the Roman institutions, and the Populars , who represented the interests of the people. With the events in the years 133/132 BC The age of civil wars began, which was to end about a hundred years later with the transformation of the republic into the empire .

Sulla spent his youth away from these political conflicts. In the theater environment and in dealing with jugglers and actors, he maintained a permissive lifestyle. In addition to the marriage with an Ilia, who died early, and an Aelia, of whom only the name is known, Sulla had a relationship with the prostitute Nikopolis, who even appointed him as heir. But it wasn't until he inherited his stepmother's fortune that Sulla had the means to embark on a professional career.

The Jugurthin War

After an intense election campaign, Sulla was elected in 107 BC. Chr. To Quaestor selected. He was assigned to the army of Gaius Marius , which operated in North Africa and was supposed to bring the war against the Numidians , which was overshadowed by the corruption of the senators, to a successful end.

The conflict with Numidia, a Roman vassal kingdom, began after the death of King Micipsa in 118 BC. When a dispute for the throne broke out between the two biological sons Adherbal and Hiempsal I. Jugurtha , who, as an illegitimate son, had the lowest claims in the line of succession, tried to use this dispute and to usurp all power in Numidia. When Jugurtha waged war against Adherbal and defeated Adherbal at Cirta , he became an enemy of Rome, since a large number of Romans and Italians had been killed in the attack. The contract negotiations that followed soon after in Rome failed. In the now decided war against Jugurtha, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Numidicus was able to bring about some successes, but no final decision, since Jugurtha's fast cavalry repeatedly withdrew from the fight with the Romans. Jugurtha had also succeeded in winning Bocchus of Mauritania on his side.

In this situation, Sulla was able to prove himself in the first military commands that fell to him. He led the very weak and inferior Roman cavalry reinforcements from his allies and from Latium and handed them over to the general Marius. After Cirta was conquered by Roman troops, Bocchus feared for his rule and started negotiations with the Romans. These peace negotiations were conducted on the Roman side by Sulla, who was able to win Bocchus' trust earlier when he advised and generously supported a Mauritanian embassy during their trip to Rome. Thanks to this trust, the unsuspecting and unarmed Jugurtha was lured into an ambush and captured by means of a staged negotiation, thus ending the war. By openly claiming the end of the Jugurthin War by making a signet ring and minting coins, Sulla achieved some fame that secured both his social position in Rome and his further career. However, this behavior worsened his relations with Marius, the actual general of the war, lastingly.

Nonetheless, Marius was seen as the victor in Rome and he was granted a triumph in which he had Jugurtha carried along. In the eyes of the Senate, the victory enabled Marius to stop the threatening German invasion, and he was therefore approved for the year 104 BC. And elected consul for the following four years. The army reform of Quintus Caecilius Metellus, which had already begun in the Yugurthin War, led Marius to a conclusion by converting the Roman military into a professional army. Since the wars against Carthage , Italian farmers returning home from the war have found it increasingly seldom possible to earn a living on the family estates that have since been deserted. The latifundia , which increased in size at the same time , were mostly managed by slaves. After twenty years of service, the veterans' pension was only guaranteed if their general provided them with land. As a result, the soldiers' loyalty was permanently tied to the general and not to the Res Publica . The resulting concentration of power was an important factor in the genesis of the civil war .

Cimbri and Teutons

The conflict with the Germanic peoples had already broken out during the Numidian War. As a result of the devastating floods, a number of tribes that were resident in Jutland and the north German plains sought new settlement areas. These tribes included the Cimbri , the Teutons , the Ambrones, and the Haruds . The Roman army suffered numerous defeats against the powerful Germanic migrant tribes who traveled through all of Gaul and even parts of Spain , lost in a battle at Arausio on October 6, 105 BC. 80,000 Romans allegedly lost their lives.

In the German war of 104 BC In BC Sulla, who served as a legate and military tribune under Marius, was able to capture Copillus, the leader of the Tectosages , and secure Roman supremacy. As a military tribune, he drew in 103 BC. By negotiating the tribe of the Martians on the side of the Romans. Due to the deteriorating relationship with Marius, Sulla was transferred to the two legions of Quintus Lutatius Catulus in northern Italy. But while Marius was in the summer of 102 BC. BC defeated the Ambrons and the Teutons, the army of Catulus and Sulla could not hold their position and had to retreat behind the Po . The time of year was too far advanced for Roman troops to defeat their opponents in northern Italy.

For the year 101 BC BC Marius gathered all available troops and in the summer of that year pushed 55,000 men against the Cimbri, who were defeated in the Raudian fields near Vercellae . Through the German War and his service under Catulus, Sulla strengthened the connection to the Optimates.

Provincial politics

It was initially difficult for Sulla to continue his political career. He had reached the bursary as soon as possible. He did not aspire to the office of aedile , as this included administrative tasks and jurisdiction, which, in view of the domestic political situation, quickly put the incumbent between the fronts. He therefore applied in 98 BC. BC, at the earliest possible point in time, around the praetur , remained unsuccessful. In the following year he applied again for the office. This time he was able to win the election of praetor urbanus by buying votes and promising the people that he would hold games as the future praetor . He had the ludi Apollinares - games in honor of Sulla's favorite god Apollo - held generously .

As a praetor he gained insight into jurisprudence and administration. Cilicia was transferred to him in the following year as governor connected with the office , whether as a propaetor or as a legate with proconsular authority, remains a matter of dispute. Sulla's area of responsibility there crossed with the interests of the Pontic king Mithridates VI. who wanted to expand his influence in that area at the time. After the fall of the Cappadocian royal dynasty of the Ariarathids , Mithridates had driven Ariobarzanes I from Cappadocia and installed his confidante Gordius as ruler. Ariobarzanes fled to Rome and asked the Senate for assistance.

In the summer of 96 BC Sulla raised an army to force the repatriation of the Cappadocian king. In Cappadocia he met the army of Mithridates VI, consisting of Cappadocian and Armenian units, which he pushed back to the Euphrates in the same year . There he reached Orobazos, an envoy of the Parthian king Mithridates II , who wanted to bring about a fundamental settlement between the two states on a peaceful basis with Sulla. It was the first contact between the two empires. Sulla was able to present himself skillfully by taking a seat in the middle during the negotiations, so that only the two side seats were left for Ariobarzanes and the Parthian ambassador. During these events a Chaldean seer is said to have predicted a great future for him.

The first consulate

As a promagistrate in Cappadocia, Sulla had confiscated substantial sums of money and was suspected of unlawful personal enrichment. After his return to Rome, probably in 92 BC. A certain Censorinus formally accused him. Legal prosecution was unsuccessful, however, presumably because a majority of the Senate wanted to build Sulla as an opponent to Marius.

Nevertheless, the procedure had drastically reduced Sulla's chances of getting a consulate, so that he initially decided not to apply. At Sulla's request, and probably with the consent of the Senate, Sulla's confidante in the Yugurthin War, Bocchus I, presented his services in 91 BC. Chr. An elaborate monument as a consecration gift on the Capitol Hill , which Sulla represented as the victor in the Numidian War. Although Marius Sulla accused Sulla of having wrongly adorned himself with the glory of victory, there was initially no serious argument due to the impending alliance war.

Marcus Livius Drusus had himself 91 BC. To be elected to the tribune of the people in order to deal with the problems of the so many disadvantaged Italians and to give them citizenship . Furthermore, the jury should be formally reassigned to the Senate and filled with 300 knights . In addition, he wanted to enforce old popular demands, such as the cheaper distribution of grain to Roman citizens, new settlements and the establishment of colonies . The Senate and supporters of the nobility opposed this plan in the strongest possible terms. Finally, the consul Lucius Marcius Philippus declared the laws to be illegal. A little later Drusus was murdered.

The death of Drusus led to the outbreak of the alliance war . Sulla joined the army of Lucius Julius Caesar as a legate , making the fight against the Samnites , who played one of the main roles in this conflict, a personal matter, like his ancestors. Rome's general suffered numerous failures. Thus, Marcus Claudius Marcellus failed to prevent the city of Venafrum from falling away from Rome. Even Sulla was not immune to failure when he was surprised by the Samnites and their allies and had to withdraw with his army. The Roman failures, apart from Nuceria and Accerae , caused numerous cities to secede from Rome. In view of the worsening situation, Lucius Julius Caesar, who in late autumn 90 BC After returning to Rome in the 3rd century BC, he incorporated the lex Iulia de civitate sociis danda , with which all allies who had remained loyal up to now were granted Roman citizenship.

In order to win the rebels for the Roman cause, the tribunes Marcus Plautius Silvanus and Gaius Papirius Carbo brought soon after taking office in 89 BC. BC introduced the lex Plautia Papiria , through which all insurgents who reported within 60 days were granted citizenship. In the same year, the military leadership reorganized. Sulla took over military command from Lucius Iulius Caesar, who was elected censor , while Marius was replaced by Lucius Porcius Cato due to his age and his lack of decisiveness in waging war . Sulla's conquests of Stabiae and Herculaneum enabled him to attack the heavily fortified city of Pompeii . The commander of the federal army, Gaius Papius Mutilus , sent a relief army under the direction of Lucius Cluentius against Sulla's troops. In the battle that followed Cluentius was crushed. The army awarded Sulla the grass wreath for his military successes . Pompeii, which now had no outside help, surrendered in the autumn of 89 BC. Finally, Sulla took Bovianum , the capital of the Samnites.

His military successes in the civil war and his good knowledge of Cilicia qualified Sulla for the war against Mithridates VI. of Pontus, and he was therefore easily found in the year 88 BC. Elected consul with Quintus Pompeius Rufus , whose son of the same name had married Sulla's daughter from his first marriage. After his election, Sulla allied himself with the powerful Meteller family by separating from his third wife Cloelia due to infertility and marrying Caecilia Metella Dalmatica , the widow of Marcus Aemilius Scaurus , who was one of the leading figures of the republic, in his fourth marriage . From the Meteller's point of view, a connection with Sulla was interesting, as he formed a counterweight to Marius and the Popularen thanks to his military skills . Through the consulate, Sulla received the province of Asia by lot and thus the supreme command in the war against Mithridates.

The first march on Rome

Sulla needed funds for his war plans. In addition, the war of allies had not yet completely ended and Sulla was forced to resume the siege of Nola, in the course of which he also conquered the Samnite camp. But the new citizens question forced Sulla to return to Rome.

Publius Sulpicius Rufus took on the interests of the allies and wanted to incorporate the new citizens and freedmen who had fought on the Roman side into the 35 existing tribes . The Senate, on the other hand, wanted to assign the new citizens to their own tribe with unequal voting rights. Furthermore, Sulpicius demanded not only the exclusion of over-indebted members of the Senate, but also that Sulla be withdrawn from command in the Mithridatic War and transferred to the popular Marius, who now lives as a private citizen.

The consuls Sulla and Pompey Rufus tried in vain by a religion-based business down the holding of a public meeting, to be voted in the laws of Sulpicius to prevent. There was a riot. Both consuls had to flee. Sulla sought protection in the house of Marius and had to agree to the Sulpic laws under threat of violence. He then withdrew to his army, which was already under his command in the alliance war, to Nola . In the meantime, through Sulpicius' initiative, Marius had received supreme command of this army for the war against Mithridates. When two military tribunes wanted to take over Sulla's army at Nola according to the decision of the people's assembly, they were stoned by Sulla's soldiers. Sulla is said to have previously reminded his soldiers in a speech that Marius could go to war with another army and withhold the rich booty in the east from them, who had served loyally in the war of allies. After the death of the military tribunes, his soldiers appealed to Sulla to march against Rome, whereupon all officers except one quaestor refused to obey. Sulla was the first Roman (since the legendary Coriolanus ) to lead an army against the capital.

The city of Rome with its largely outdated defenses could hardly resist such a large army, which Sulla had divided into several groups to attack. The capture of Rome represented Sulla as the salvation of the state. He ordered the Senate to declare twelve persons of the political and military leadership of the Popularen to be enemies of the state and to call them to be searched and executed, although he did not do so without asking the people and appointing a jury was authorized. The persecuted were also denied the right to provoke . All laws and orders of Sulpicius were annulled. He himself was captured and killed while Marius managed to escape to the province of Africa .

Sulla has now passed some laws to install the Senate as the final decision-making body and to curtail the influence of the People's Tribunate. For example, the Senate had to give its approval to bills from the tribunes, and decision-making was shifted from the tribute committees to the central committees . This not only significantly increased the influence of the knights and members of the Senate in elections and votes, but also after violent disputes in the year 241 BC. Adopted voting procedure unceremoniously withdrawn. The Senate was also expanded by 300 optimistic members. In addition to these three laws mentioned by Appian , a law on the establishment of colonies and a debt law are mentioned.

Sulla's further action was probably of a provisional nature, as immediate action against Mithridates was absolutely necessary in order to preserve the credibility of Rome in the east. However, he recognized that the political structures needed a time-consuming reorganization. Under pressure from his followers, Sulla had consular elections for the year 87 BC. Perform, which, however, showed its declining popularity with the Roman people and with their followers. Because in addition to Gnaeus Octavius , who was favored by Sulla , Lucius Cornelius Cinna, a declared supporter of Sulpicius, prevailed. The failure of the attempt to have the army of the proconsul Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo handed over to his counterpart Quintus Pompeius Rufus was also reflected in Sulla's declining support, as Pompey Rufus was killed by the soldiers a few days after taking command. In the conflict with Cinna, Sulla contented himself with his oath not to commit any hostile acts and, as proconsul, crossed with his army from Brundisium to Epirus .

Rome and Italy 87–84 BC Chr.

Cinna broke his oath and brought out Sulpicius' legislative initiative to assign new citizens to the tribes. His fellow consul Octavius mobilized the people against Cinna's plans. In street battles, Cinna's followers were defeated by Octavius, and Cinna was declared a hostis , an enemy of the state. He fled via Praeneste to Nola, where he was able to win over the troops and the new citizens for his cause by means of large bribes and called back the aged Marius from exile in North Africa.

Towards the end of the year 87 BC Cinna and Marius took Rome. A number of aristocrats fell victim to the terror that followed, so Octavius was murdered as well as Marcus Antonius , while Quintus Lutatius Catulus escaped Marius' vengeance by suicide. Sulla's wife Caecilia Metella and Aemilia , her daughter from her first marriage, and the newborn twins Cornelia Fausta and Faustus Cornelius Sulla went to Greece in the camp of her husband. Sulla's house was destroyed, his property confiscated and he himself ostracized. The Victory Monument on the Capitol was razed to the ground.

In the year 86 BC Cinna and Marius were elected consuls. Marius was able to take up his seventh consulate before succumbing to pneumonia a few days later and being replaced by Lucius Valerius Flaccus . Cinna became the most powerful figure in Rome for the next three years: Laws were no longer passed by calling the people's assembly, but by Cinna's decision. Cinna appointed his fellow consuls directly. He himself held the consulate continuously from 87 to 84 BC. But Cinna knew that his future depended on the outcome of Sulla's fighting in the east. He had an army of two legions raised and, under the command of Valerius Flaccus, in the summer of 86 BC. To Greece. After Flaccus was murdered by his troops, his successor Gaius Flavius Fimbria continued his operations against Mithridates independently of Sulla. Cinna itself was born in 84 BC. Slain by mutinous groups in Ancona .

The First Mithridatic War

Mithridates VI., King of Pontus , continued his father's policy of expansion purposefully and on an even larger scale. Since the inhabitants of the province of Asia were exploited by the Roman administration and the alliance and civil war paralyzed the Roman clout, Mithridates saw the time had come to begin his major offensive. To justify himself, he proclaimed himself the liberator of the Greeks from the Roman yoke. To fill his war chests, Mithridates ordered the murder of all Italians and Romans. According to Valerius Maximus , followed by Memnon of Herakleia , 80,000 Italians and Romans lost their lives by this blood command from Ephesus . The break with Rome was thus final. Mithridates VI. offered at the beginning of the year 88 BC An army of 250,000 infantrymen, 40,000 riders and 130 sickle chariots. It consisted of uncoordinated, ethnically inhomogeneous associations.

In the spring of 87 BC BC Sulla crossed over to Epirus with five legions and a small number of horsemen. Sulla moved slowly through Aetolia to Thessaly , in order to persuade the fallen Greek cities to surrender by the presence of a large army. Before the summer of 87 BC Sulla had large parts of Greece under control again and forced the commanders of Mithridates, Aristion and Archelaus , to retreat to Athens and Peiraieus . A first attack by Sulla on the Pontic base of Peiraieu failed, however. To be able to take the city, Sulla had a siege ring drawn around the Peiraieus. Sulla met less resistance in Athens, where he learned that a section of the wall was no longer adequately occupied. Through this breach, Sulla's troops were able to escape in March 86 BC. To enter the city unhindered. Aristion managed to escape. Only when the murder and plundering of the city went too far for some Roman senators did Sulla stop his soldiers.

In the meantime the popular army under Fimbria advanced further into Asia Minor, subjugated individual associations of Mithridates of Pontus and sacked Ilion . Fimbria even succeeded in locking Mithridates himself at Pitane , but on Sulla's instructions, the fleet commander Lucullus let him escape at sea.

After Athens had been taken, Sulla finally succeeded in conquering Peiraieus with a larger number of troops with considerable Roman losses. This enabled him to bring the base of operations of the Pontic troops on the Greek mainland under his control. In the spring and autumn of 86 BC Sulla faced the Pontic troops at Chaironeia and Orchomenos . In both battles he had wide trenches dug to obstruct the Pontic cavalry and chariots. Thanks to his vast military experience and the discipline of his army, Sulla was able to defeat the outnumbered enemy in fierce battles.

Reorganization of Asia Minor and confrontation with Fimbria

With the Battle of Orchomenos, Roman rule over the Greek city-states was defended. The remnants of the Pontic army were in Euboea and Chalkis . However, since Sulla had no fleet, it was not possible for him to take Evia. Under these circumstances, a continuation of the war against Mithridates in Asia Minor and especially in its Pontic base could have lasted years and thus kept Sulla away from Rome. On the other hand, a determined opposition to Mithridates formed in many cities in Asia Minor, which Rome was able to use for itself. In this stalemate, the war was ended by the peace treaty of Dardanos in 85 BC. Ended. Sulla granted the Pontic ruler a favorable peace: he had to give up his conquests, pay 2,000 talents and hand over 70 fully equipped warships. Mithridates was even honored with a hug and kiss as a Roman ally, while Sulla demanded 20,000 talents from the cities in Asia that had joined him.

Ephesus was particularly severely punished for having followed Mithridates too readily. The city lost parts of its territory, the leaders of the anti-Roman party were executed and the city was sacked. Klazomenai , Miletus and Phocaea lost their freedom, and Pergamum , the residence of the Pontic king, suffered badly from Sulla. In addition to Sulla's violent measures, the cities were also heavily burdened financially. First Sulla quartered his army in the cities and obliged them to take care of the soldiers. The common soldier cost the citizens 16 drachmas a day, a centurion received a wage of 50 drachmas a day. Furthermore, the cities had to pay the back taxes for the years 88–84 BC within one year. Chr. Pay. In addition, the cities of Asia Minor had to bear the costs of the war and the reorganization of the province, which were estimated at 20,000 talents. As massively as Sulla punished the Greek cities that had taken part in the war against Rome, the loyal cities were generously rewarded. Ilion, Chios and communities in Lycia and Rhodes were granted considerable privileges.

After the reorganization of Asia Minor, Sulla moved against Fimbria and met him at Thyateira . Sulla asked him to hand over his army to him, as he was not legally in command. When Fimbria in return questioned the legality of Sulla's authority, Sulla had the siege of Thyateira prepared. The size of his army and his prestige caused the soldiers of Fimbria to overflow into Sulla's camp. Fimbria, who could no longer persuade his soldiers to be loyal and whose attempt to murder Sulla failed, fled to Pergamon, where he committed suicide.

The Second March on Rome

After the peace treaty of Dardanos and his victory over the popular army of Fimbria, but also thanks to the possession of large sums of money and resources, which ensured the loyalty of the army to the general, Sulla was now able to deal with the domestic opponent.

According to Appian , the army with which Sulla met at the beginning of 83 BC. Was embarked on allegedly 1,600 warships to Brundisium, a strength of 40,000 men. The opposing commanders, the proconsul Papirius Carbo and the incumbent consuls from 83 BC BC, Gaius Norbanus and Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus , with their armed forces of 100,000 soldiers did not resist the landing of Sulla. In doing so, they gave up the opportunity to confront the invaders in Calabria , Apulia and Lucania and to push into Sulla's attack formations while they were being formed. Many soldiers ran over to Sulla's army. Marcus Licinius Crassus , the later triumvir and richest man in Rome, offered an army formation from Africa , and Gaius Verres , Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Lucius Sergius Catilina also joined the Sulla cause. Even former opponents sought their salvation in defection, such as Publius Cornelius Cethegus, the consular Lucius Marcius Philippus and the knight Quintus Lucretius Ofella.

In Rome the consuls of 83 BC organized BC, Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus and Gaius Norbanus, the defensive battle against Sulla. The first major battle took place in the spring of 83 BC. At Mount Tifata north of Capua . In the following battle Norbanus was defeated and had to retreat to Capua with the remnants of his army. Sulla received favorable news from other fronts as well. Pompey had been able to strengthen his troops in Picenum and defeat popular armies in several battles, including the army of Carbo at Ariminum , which had occupied a central position in the Gallia cisalpina . Meanwhile, Scipio lost his army through desertion, and Crassus was able to carry out recruits for Sulla's army in the tribal area of the Martians. In addition to the shortage of soldiers, the popular leadership faced financial problems, as the long war period had emptied the state coffers and now the temple treasures had to be used to finance the war.

In 82 BC In BC Carbo and Gaius Marius the Younger were elected consuls because they were hoped for new accents in the battles against Sulla. The younger Marius faced Sulla at Sacriportus and was defeated in the following battle near Signia and driven back to Praeneste . Quintus Lucretius Ofella was entrusted with the blockade of the city , the fighting spread mainly in Etruria as far as Gaul . In numerous other battles, the Sullan commanders Crassus, Metellus and Pompey prevailed. After their defeats, Carbo and Norbanus gave up and fled, Carbo to Africa and Norbanos to Rhodes. The associations that had become leaderless disbanded or were destroyed by Pompeius.

The Samnites and Lucanians , allies of the Populares, realized that they were now in serious danger. They marched from their position in Praeneste to Rome and set up camp near the Porta Collina . Sulla, observing the enemy movements, moved to Rome and met them at the Porta Collina. In bitter fighting, the left wing under Sulla's leadership broke in, and Sulla's only success remained in rallying the demoralized troops in the camp. On the other hand, the right wing under Crassus was able to achieve a complete victory and throw the Samnites and Lucanians back to Antemnae .

Because of Sulla's military superiority, the assembled senators could not avoid confirming him in his proconsular office. At the same time, all of Sulla's resolutions in the east and all of his measures against domestic opponents were approved. On November 3rd, several thousand Samnites were trapped on the Field of Mars in Rome and killed with spear throwing. The slaughter of the opponents on the sacred ground of the Martian field could have been religiously motivated and thus intended as a human sacrifice , which had only been officially prohibited a few years earlier. A few years earlier Marius had ritually killed domestic political opponents, later Caesar and Augustus were to repeat this in civil war situations. After Sulla's victory at the Porta Collina, Praeneste could no longer be held as the last base of the Popularen under the command of the younger Marius. Marius himself chose suicide after a failed attempt to escape. Those trapped in Praeneste, who finally surrendered, were mostly killed and the city plundered.

dictatorship

Establishment of the dictatorship

With the death of the two consuls Gaius Marius the Younger and Gnaeus Papirius Carbo in 82 BC. The state was deprived of its leadership. In this case, there was the authority of Interrex (“intermediate king”) as the regulating body, whose responsibility it was to hold consulate elections as quickly as possible. For Sulla it was crucial that the chosen Interrex would serve his interests completely. For this reason, Sulla helped Lucius Valerius Flaccus to the office of Interrex in the Senate meeting on November 5 . In a letter that has only survived from Appian, Sulla informed the Interrex Flaccus that whoever would be elected could remain in office until the situation in Rome and Italy were rearranged. At the end of the letter, Sulla agreed to take on this important position.

During this process, Sulla stayed outside Rome to maintain the appearance that the people were choosing dictatorship voluntarily. Due to the temporary nature of its office, Interrex was not able to create exceptional political power without a time limit. That is why Interrex introduced the lex Valeria, a law to establish a dictatorship, before the popular assembly . After the adoption of the law by the popular assembly, Sulla was appointed dictator by the Interrex Lucius Valerius Flaccus . The lex Valeria regulated competence and duration of the office. With regard to competence, Appian passed on what is known in Latin as legibus scribundis et rei publicae constituendae (“to give laws and to regulate the state”), with regard to the duration of the dictatorship, that it was unlimited in time.

Criticism of this authority, which was not compatible with old Roman law, was severely punished by Sulla, even in her own family. So he forced 82 BC His newlywed and pregnant stepdaughter Aemilia for divorce because her husband Manius Acilius Glabrio had expressed himself critical of his politics, and she married his protégé Pompeius.

Legitimacy of the dictatorship

Sulla tried to legitimize his future actions before and during his dictatorship through incomparable honors. This includes the award of the Cognomen Felix to Sulla. The exact date of the award is controversial: Appian reports that Sulla received the nickname even before his appointment as dictator; According to Plutarch, on the other hand, Sulla is said to have acquired this surname as a dictator by edict. With the cognomen Felix Sulla wanted his dictatorship to be understood more as the logical consequence of divine will and less as the result of a planned action towards it. Since he was given the felicitas by the gods , he should be able to save the community and consolidate the state. Furthermore, with this nickname, he was able to allude not only to past military, but also to domestic political achievements to be made, which were foreseeable as a result of his "luck". As the patron goddess of Rome, Felicitas has been venerated since the royal era because of her responsibility for the size and security of the res publica . This self-assessment as a favorite of divine happiness was reflected in the naming of his before 86 BC. Fourth marriage twins born in BC, whose nicknames Fausta and Faustus also mean "happy".

As a further honor, Sulla had a golden equestrian statue set up on the forum; this distinction was also spread on coin images. That statue was near the statues of the dictator Marcus Furius Camillus and the Samnite victor in the 4th century BC. BC, Quintus Marcius tremulus . Formally, this honor was justified with the victory over the Samnites in front of the Porta Collina, whereby the material, gesture and the traditional location of the statue were intended to underline Sulla's claim to leadership. At the end of January of the year 81 BC In BC Sulla celebrated a triumphal procession over Mithridates VI., Which could also be understood as a triumph over the opponents defeated in the civil war - a unique event until then, as the ritual-bound triumph was only necessary for a victory in a just war, a bellum iustum , granted. The triumph, like the other honors, was part of Sulla's propaganda concept, since Mithridates was neither conquered in battle nor carried along in triumph. With the triumph, however, it was suggested to the Roman people that the agreement with the Pontic ruler was equated with a victory. Through the triumph, Sulla was praised by the people as “Savior and Father”.

The triumph also distracted from the ongoing proscriptions and presented the population with the rich booty of the war. Despite all the honors, Sulla knew that the Roman people, the plebs urbana , were fickle and would by no means support their policies. He remembered the benefits he had drawn from carrying out the ludi Apollinares in earlier times . At that time Sulla had celebrated the Games generously in order to become praetor. So he now used the games for his own purposes and had the ludi victoriae Sullanae held, which, which was a novelty, was to be celebrated not just once, but annually in the future from October 26th to November 1st. In order to inspire the Roman people, these games were celebrated particularly lavishly and Sulla is said to have been extremely generous. He had food and drink brought in in abundance, so that later the remains had to be thrown into the Tiber . Sulla wanted with these games equally to his victories over the Italians and Mithridates VI. recall.

Proscriptions

Even before his appointment as dictator, Sulla had initiated the proscriptions . The legal basis of the proscriptions was subsequently created with the lex Valeria , which also regulated Sulla's appointment as dictator. It contained both the approval of the proscriptions that had already taken place and the authorization to continue the mass killing of political opponents.

As one of his first official acts as dictator, Sulla introduced a law at the end of December that was to regulate the legal consequences of the proscriptions in detail. In terms of content, the law stipulated that the proscribed could be killed by anyone. A reward of 12,000 denarii was offered on the head of a proscribed person . Aid to a proscribed person was subject to the death penalty.

The proscriptions ended on June 1, 81 BC. According to tradition, the number of those killed was 4,700 Roman citizens. The list entry did not offer any legal security, as the lists were not checked and therefore supplemented at will. Some people who had fallen victim to robbery were also added to the list.

Sulla saw the deceased Marius as the main person responsible for the humiliation he experienced. The tomb of Marius was desecrated and his remains thrown into the Anio . Sulla had the victory monuments of Marius demolished. The later dictator Caesar was also persecuted by Sulla and only pardoned through the mediation attempts of the Vestal Virgins and Sulla's friends. The persecution of the political opponents was not limited to their person, but Sulla's revenge did not stop at the children and grandchildren of the outlaws, who lost the political privileges of their class; the entire family was to be wiped out of political life.

Sulla's proscriptions also changed ownership. The goods of the slain proscribed and Sulla's enemies were sold. So much land went under the hammer at the auctions that prices plummeted. This enabled Sulla's followers to amass large assets and vast land holdings. One of the most successful was Marcus Licinius Crassus , who rose to become the richest Roman through proscriptions. Also Chrysogonos , a freedman of Sulla, enriched himself considerably. He was able to acquire the goods of Sextus Roscius for the three thousandth part of their value. As can be seen in the defense speech of the young speaker Marcus Tullius Cicero for Sextus Roscius, Chrysogonus's greed for money was responsible for murder and expropriation in this case too. Plutarch judged: “and those killed out of hatred and enmity were only a tiny minority compared to those killed for money; yes, the murderers dared to say that one person was killed by his large house, another by his garden, and another by his hot baths. ”A total of 350 million sesterces reached the state treasury through the auctions .

Constitution

Sulla's body of law was aimed at strengthening the Senate, weakening all other institutions and finally securing the system across the board. It should take back the Gracchian reform attempts .

Sulla turned the criminal courts over to the senators and created seven new quaestiones to serve as permanent courts. He opposed any form of politicization of the equestrian order initiated by Gaius Gracchus, which had the aim of building an estate that rivaled the Senate. Rather, Sulla wanted to integrate loyal members of the knightly class into the ruling class by accepting them relatively generously into the Senate.

He tried to compensate for the weakening of the Senate as a result of the losses suffered in the civil war and through the proscriptions, which contradicted the major role that the Senate was to play in Sulla's draft constitution, by increasing the number of senators from 300 to 600. The enlargement of the Senate was also necessary in order to have enough senators available to fill the courts. After the Senate was enlarged, almost three-quarters of the committee consisted of political newcomers whose families were not traditionally among the leaders of the republic. Sulla's changes were an epochal upheaval in the personal structure of the Senate that had never happened before.

Sulla also changed the modalities of admission to the Senate. Up until now , the censors had decided on admission to the Senate based on their lifestyle and financial situation and, thanks to the nota censoria (“reprimand of the censors”), could remove someone from the committee. However, since this process was highly subjective, Sulla determined that access to the Senate should be automatically granted if the candidate held the bursary. At the same time he increased the number of quaestors from about 10 to 20. Since the censors were thus deprived of almost all competences, in the period from 86 to 70 BC, No more officials appointed.

Sulla gave the consulate an important role. In his constitution he laid down the official career path Quaestur - Praetur - Consulate binding. Because the candidates had often tried to skip the praetur in order to reach the consulate as quickly as possible and to avoid the unpopular praetur, for which a multitude of sayings and laws had to be mastered. It was no longer possible to skip the praetur. For this, the number of annual office holders of the bursary and praetur was increased. Furthermore, Sulla set the minimum age for the office. The bursary as the entry office could be filled from the age of 30, the praetur from the 40th and the consulate from the 43rd year of life. Re- application for the office of consul ( iteration ) was only possible after 10 years. The first victim of this new arrangement was Quintus Lucretius Ofella . He had made a military contribution to the siege of Praeneste and applied for the consulate, although he had held neither the bursary nor the praetur. When Ofella refused to accept Sulla's veto, the dictator had him killed.

In the provincial administration, Sulla stipulated that the two consuls and the praetors, who had now increased to eight posts, would do their one-year service in the capital and then assume governorship as proconsuls or proprata. The propaetors were entrusted with the governorship of one of the smaller provinces for one year. Sulla wanted to prevent an abuse of power by the governors. The Senate therefore regulated the distribution of the provinces. The governors had to leave the province within 30 days of the arrival of the successor. Crossing the provincial borders and thus conducting a war that was not approved by the Senate was forbidden to them, as was irregular leaving the area of responsibility.

With the strengthening of the Senate, Sulla also severely restricted the powers of the People's Tribunate. With immediate effect, the assumption of the position of the people's tribune prevented a further rise in the system of magistrates, and the people's tribunes had to have the Senate confirm every legislative proposal they wanted to submit to the people's assembly. Also, the tribunes could no longer veto any state measure, but only when a citizen needed support against the order of a magistrate. Through these measures, the people's tribunate was again limited to the basis of direct assistance to fellow citizens, as it was at the beginning of the class struggles in the 5th century BC. Was the case. The regulation was intended to prevent politically ambitious and talented applicants from using the People's Tribunate as a platform for their further policy. Only his respect for the institutions of the res publica - which was strongly influenced by an optimistic attitude - and his fear of excesses by the urban Roman population probably prevented Sulla from completely abolishing the office.

Although Sulla had assumed the role of dictator legibus scribundis et rei publicae constituendae (dictator for the drafting of laws and the reorganization of the state), he had the Comitia Centuriata vote on all his Leges Corneliae in accordance with the Roman constitution . But after the radical elimination of political opponents, resistance to Sulla's legislative initiatives was hardly to be expected.

Constitution of order

Sulla took numerous measures to secure his reform work. He put many political friends in influential positions. Sulla intended to bind entire families and their power to his own person, primarily through a targeted marriage policy. These people were also called Sullani because of their close ties to the dictator .

Military and social security should be provided by veterans' settlements. According to Appian, 23 legions were provided with land. Sulla's soldiers were rewarded for their actions through the veterans' settlements. Sulla largely renounced the establishment of colony, since he settled his soldiers in those Italian cities that had fought him on his conquest. The soldiers were provided with the land and houses of Sulla's opponents who had been driven out, dispossessed or killed. The land was probably not handed over to the veterans as private property (ager privatus optimo iure) , but rather it probably had the legal status of ager publicus and was therefore subject to a ban on sale.

To further support the system, Sulla granted civil rights to over 10,000 young slaves of the proscribed. From then on they bore his name and were known as Cornelii . Sulla thus had numerous followers among the free population.

Abdication and death

At the beginning of the year 79 BC BC Sulla laid down the dictatorship before the Roman people's assembly . He communicated his decision to the assembled people and agreed to give an account. Various considerations have been made in research about the specific reasons for resigning from office. Political, personal, and religious-spiritual motives come into consideration. On the one hand, it is assumed that Sulla's resignation was in line with constitutional tradition because he saw his mandate, the restoration of the constitution, as successfully completed. Karl Christ also assumes that Sulla wanted to avoid the negative precedent of an excessively long dictatorship by abdicating. In addition, he argues that the long years of civil war and the subsequent domestic political quarrels caused Sulla to become disaffected with politics, even in view of his old age, so that he turned to rural life. According to Plutarch , a Chaldean is said to have once predicted that he would die after a glorious life on the peak of happiness, from which, according to Hans Volkmann , Sulla heard the warning to finish his work as soon as possible if he wanted days of rest .

After the abdication, Sulla and his fifth wife Valeria left Rome to return to the permissive lifestyle of the early years on his property at Posillipo near Puteoli . In addition to hunting and fishing, he wrote his memoirs in 22 books, which have not survived but were used as a source by later authors. He also ended the clashes in Puteoli between the old citizens and the veterans who had settled there by giving the city a new constitution. In 78 BC Sulla died of a hemorrhage , allegedly due to his conflict with Granius , the duumvir of Puteoli. On the initiative of the consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus and Pompey, the Senate decided on the first state funeral of the late Roman Republic. According to Karl Christ, his funeral served partly as a model for the later burials of Caesar and the Roman Principes.

effect

Just eight years after his death, Sulla's important laws were withdrawn. Thus the legislative initiative of the People's Tribune was fully restored. The people's tribunate, which since the Gracches had often triggered socially motivated violence and since then has developed into an instrument of power for popular politicians, again represented an opposition to the Senate. The exclusive appointment of the courts of justice with senators was repealed. The censorship was also restored, which made restructuring of the senatorial class possible. Sulla solved the urgent domestic political problem of veterans' care in his favor, but did not create a permanent settlement; because the sale ban introduced, which pursued the purpose of securing the beneficiaries of the Sullan order in the long term, failed. Many veterans got into debt and found ways and means to sell the assigned land again.

Sulla's reform of the senatorial office career lasted to a large extent. As entry into the Senate, the bursary remained just as binding as the governorship, which was linked to the two highest offices. Augustus made few changes to the Senate order inherited from Sulla, and he reduced the number of senators back to 600 after Caesar had temporarily increased it to 900. Sulla's systematic order of the administration of criminal justice and some of his laws were effective well into the imperial era.

Antique picture of Sulla

Sulla's image in antiquity was shaped by his memoirs, which with their self-portrayal and justification continued into the 2nd century AD. However, the new activation of the Marians initiated by Caesar reinforced old anti-Sullan tendencies. These contradicting positions are reflected in the ancient sources insofar as positive elements and achievements were recognized up to Sulla's victory at the Porta Collina, but afterwards the dictator was discredited as the classic embodiment of the crudelitas (cruelty) of a tyrant.

Historians who write in Latin do not offer a comprehensive and closed image of Sulla. The two main sources about the Sullan era are the Greek-language works of Appian and Plutarch. In Plutarch's parallel biographies, in which the moral and ethical criteria of classical and Greek philosophy predominate, Sulla is often viewed as a typical Greek tyrant, whereby his bravery and martial arts are positively valued. On the other hand, the depiction of Sulla in Appian, who identified himself with the principate and empire out of conviction, is consistently cheap.

In research is Cicero's relationship has often been discussed to Sulla. One group saw him as a partisan, while others saw him as a neutral observer. On the one hand, Cicero resolutely rejected the absolute power position of an individual, as it would inevitably lead to their abuse, on the other hand he recognized that Sulla's dictatorship was inevitable as a means of reorganizing and saving the res publica . As 49 BC When the new civil war broke out, the memory of Sulla was present again. The consul Lucius Cornelius Lentulus Crus boasted of becoming a different Sulla, the word formation sullaturire - "to imitate the Sulla" - became a common expression.

Caesar distanced himself from Sulla's politics. He called Sulla politically illiterate because of the resignation of the dictatorship. He also contrasted his policy with his mildness, the proverbial clementia Caesaris , with which he distanced himself from Sulla's cruelty. But Caesar's policy of leniency did not work. The triumvirs Marcus Aemilius Lepidus , Marcus Antonius and Octavian again resorted to Sulla's methods with the proscriptions and justified their approach with the consequences of Caesar's generous policy of clementia . In the later Principate of Augustus, the enmity between optimates and populares was dissolved.

Strabo , who wandered through the landscapes of Samnium three generations later, recorded what the Sullan crusade had done to this country: “Sulla did not rest until he murdered or expelled all who bore the name Samnites from Italy; but to those who criticized such an anger, he said that he had convinced himself through experience that not even a Roman would ever have peace as long as the Samnites continued to exist as an independent people ”. For Strabo, this goal had been achieved so consistently that he did not want to grant the name "city" to any of the remaining villages in Samnium. The philosopher Seneca used Sulla as a deterrent example in his treatises on the gentleness of the ruler and called him a tyrant because of his mass killings. Plutarch accused Sulla of having made himself dictator and thus committed a breach of the constitution.

Under Octavian , Galba , Vitellius , Vespasian , Septimius Severus , and especially in the time of the soldier emperors and in late antiquity, there were new marches on Rome. However, only Septimius Severus openly confessed to Sulla's policy of harshness and violence in AD 197. His son Caracalla , who shared this conviction, had Sulla's tomb renewed. In the 5th century, Augustine of Hippo justified the military downfall of the Christianized Empire, pointing out that Sulla's proscriptions had exceeded the current murders of the Gauls and Goths .

Research history

A large number of special studies were presented in the research, but only a few summarizing biographies. An assessment of Sulla therefore took place primarily in the general accounts of Roman history.

Theodor Mommsen was fascinated by Sulla, who acted consistently for the cause of his class and did not succumb to the individual enjoyment of power. Mommsen's judgment on Sulla was accordingly positive from the beginning of his Roman history in the middle of the 19th century. He praised Sulla as "the noblest and bravest officer". Mommsen consistently differentiated his dictatorship from the previous form of dictatorship and concluded with the following: “Sulla is indeed one of the most wonderful, perhaps we can say one single phenomenon in history.” Leopold von Ranke, on the other hand, honored Marius in his world history to a higher degree as Sulla and saw the latter as the first monarch in republican Rome.

In the 1930s, publications appeared with particular frequency and with very different ratings. In 1931, Jérôme Carcopino , in his work Sylla ou la monarchie manquée, took the view that Sulla had striven for a military monarchy from the start. The resignation of the dictatorship had been forced in a new domestic political crisis, particularly under pressure from the consuls Appius Claudius Pulcher and Publius Servilius Vatia , but also from Pompey and a group of senators. Helmut Berve tried in 1931 to show Sulla's nature and importance of the caste of urban Roman aristocrats. He designed his Sulla picture in conscious confrontation with Theodor Mommsen and drew a negative conclusion: "In the cold impersonality and rigid monumentality of his work, in his class and political bias, he appears as the last old Roman." On the other hand, Hugh Last gave in 1932 in the Cambridge Ancient History handbook series describes the history of events closely based on the representations of Appian and Plutarch. On the one hand, Last praised the social brilliance of the bon vivant, but on the other hand did not hide his contempt for all human values.

During the National Socialism, Sulla was classified by Wilhelm Weber in the New Propylaea World History with words such as “race”, “blood” and “living space” in the national socialist ideology.

In the English-speaking world, Ernst Badian in particular emerged from the 1950s with several special studies in which he dealt primarily with prosopographical and chronological questions. Badian pointed out that Roman domestic politics were only known in outline anyway. In the 1960s, Alfred Heuss placed sober constitutional aspects at the center of his presentations. According to his student Jochen Bleicken , Sulla subjected the constitution of the Roman Republic to a thorough analysis. With the help of "a completely new form of dictatorship" he began to remedy deficiencies in the constitution. Sulla's person was of little interest in the history of the German Democratic Republic , as the Spartacus uprising overshadowed the importance of the senatorial restoration under Sulla. In the French-speaking world, François Hinard's most important works were published in the 1980s. Hinard wrote a biography of Sulla and described the peculiarity of his dictatorship by comparing it with modern dictatorships.

The ancient historian Karl Christ (2002) turned in his monograph against a one-sided typological classification (the “last old Roman”, “monarch”, “revolutionary”, “restorative reformer” or “restoration terrorist”) Sulla. For a characterization, Christ put the emphasis on Sulla as a military and as a politician as well as on his relationship to the transcendental realm. Christ certified Sulla a "never challenged military authority" and honored him as one of the most successful military generals in Rome. In politics, Christ noted numerous improvements in administration and jurisdiction. Nevertheless, for Christ, Sulla was not an “outstanding statesman and politician”. During his dictatorship, Sulla assumed "two cardinal misjudgments". The ruling structure as senate and class rule could no longer permanently meet the requirements of the size of the Roman Empire in the first century BC. Chr. Correspond. In addition, the Roman ruling class was internally torn and no longer showed the unity of the classical republic. In Sulla's relationships in the transcendental realm, Christ noted that the coin designs fit into the republican tradition and do not indicate sole rule.

An isolated look at Sulla's political reform work reveals serious efforts to secure the republican constitution and Sulla appears as the “last republican”. However, many studies on Sulla take into account the fact that the excesses of violence of the proscriptions cannot be decoupled from his political activities.

Artistic reception

The best-known arrangement of the Sulla material is Mozart's opera Lucio Silla , which illustrates the generosity of an absolute ruler in Roman garb. Even George Frideric Handel in his opera treated Lucio Cornelio Silla historical person.

Christian Dietrich Grabbe described in his youth fragment Marius and Sulla (1813–1827) Sulla's doubts about his own work, the contempt for people and the world, and finally his resignation from power and his retreat into solitude. Grabbe admired in Napoleon the type of a power man and saw the despotism of the great individual embodied in Marius and Sulla.

The resistance fighter Albrecht Haushofer , who was murdered in 1945, staged life in a dictatorship in his 1938 drama Sulla and depicted the development of the self-confident general and dictator into an irritating ruler.

Fiction adaptations after 1945 come from Colleen McCullough in her novels The Power and Love and A Crown of Grass , which are based on the conflict between Marius and Sulla, as well as favorites of the gods over Sulla's dictatorship. Jutta Deegener wrote the novel Sulla. Novel about the late period of the Roman Republic .

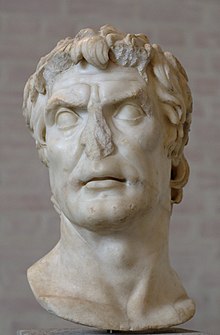

portrait

The first pictorial representation of Sulla known from literary tradition was a statue, which King Bocchus of Mauritania 91 BC. Was built on the Capitol in Rome. Sulla received numerous statues during his time in the East, and after his victory in the civil war in Italy too. The best known was a gilded equestrian statue in the Roman Forum. None of these statues has survived. The only inscribed portrait is on a coin, which Sulla's grandson Quintus Pompeius Rufus probably 55 BC. BC, more than 20 years after the dictator's death.

Numerous attempts have been made to identify an anonymous representation with Sulla by comparing it with the coin portrait. Most recently, Volker Michael Strocka has dealt with the question in detail and, like Klaus Fittschen , suggests viewing a portrait head in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen as Sulla's portrait, which is likely to come from the eastern Mediterranean. Strocka sees replicas in a statue in the Vatican, a bronze head from Verona and several late Republican gems.

Further portraits identified by individual scientists with Sulla are in turn in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek ("Sulla Barberini" and another head), the Glyptothek Munich (see beginning of the article; identification last mainly represented by Götz Lahusen ), again in the Vatican (two different Heads), Venice and Malibu.

swell

- Appian : Civil Wars . German translation: Roman history, part 2: The civil wars . Published by Otto Veh / Wolfgang Will , Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-7772-8915-9 . English translation by LacusCurtius

- Plutarch : Sulla . German translation: Great Greeks and Romans . Translated by Konrat Ziegler . Volume 3. dtv, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-423-02070-9 . (English translation)

- Sallust : Bellum Iugurthinum / The war with Jugurtha . Latin / German. Edited, translated and commented by Josef Lindauer, Düsseldorf 2003, ISBN 3-7608-1374-7 .

- Velleius Paterculus : Roman History. Historia Romana . Translated and edited in Latin / German by Marion Giebel, Reclam, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-15-008566-7 , ( Latin text with English translation ).

literature

- Holger Behr: Sulla's self-portrayal. An aristocratic politician between a claim to personal leadership and solidarity with class (= European University Theses Series 3: History and its auxiliary sciences. Volume 539). Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1993, ISBN 3-631-45692-1 (also: Frankfurt am Main, University, dissertation 1991).

- Karl Christ : Sulla. A Roman career. Beck, Munich 2002. Unchanged reprint, 4th edition 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-61724-9 .

- Hermann Diehl: Sulla and his time in the judgment of Cicero (= contributions to classical studies. Volume 7). Olms et al., Hildesheim et al. 1988, ISBN 3-487-09110-0 (At the same time: Göttingen, Universität, dissertation, 1987).

- Alexandra Eckert: Lucius Cornelius Sulla in ancient memory. That murderer who called himself Felix (= Millennium Studies. Volume 60). De Gruyter, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-045413-0 .

- Franz Fröhlich: Cornelius 392 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume IV, 1, Stuttgart 1900, Sp. 1522-1566.

- Jörg Fündling : Sulla. Scientific book society. Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-534-15415-9 . ( Review )

- Ursula Hackl : Senate and magistrate in Rome from the middle of the 2nd century BC Until Sulla's dictatorship (= Regensburg historical research. Volume 9). Lassleben, Kallmünz 1982, ISBN 3-7847-4009-X (also: Regensburg, University, habilitation paper, 1979).

- Theodora Hantos : Res publica constituta. The constitution of the dictator Sulla (= Hermes individual writings. Volume 50). Steiner, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-515-04617-8 .

- Karl-Joachim Hölkeskamp : Lucius Cornelius Sulla - revolutionary and restorative reformer. In: Karl-Joachim Hölkeskamp, Elke Stein-Hölkeskamp (ed.): From Romulus to Augustus. Great figures of the Roman Republic. 2nd edition, unchanged reprint. Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-61203-9 , pp. 199-218.

- Arthur Keaveney: Sulla. The Last Republican. Croom Helm, London 1982, ISBN 0-7099-1507-1 . Also: 2nd edition. Routledge, London et al. 2005, ISBN 978-0-415-33660-4 (Partly at the same time: Hull, University, dissertation, 1978).

- Wolfram Letzner : Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt of a biography (= writings on the history of antiquity. Volume 1). Lit, Münster et al. 2000, ISBN 3-8258-5041-2 .

- Federico Santangelo: Sulla, the elites and the Empire. A study of Roman policies in Italy and the Greek East (= Impact of Empire. Volume 8). Brill, Leiden u. a. 2007, ISBN 978-90-04-16386-7 . ( Review )

- Hans Volkmann : Sulla's March on Rome. The decline of the Roman Republic (= Janus books. Volume 9). Oldenbourg, Munich 1958. Reprint: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1969.

Web links

- Literature by and about Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix in the catalog of the German National Library

- Historical novels about Sulla

Remarks

- ↑ Based on the Greek transcription Σύλλα of the name, which can be found, for example, in the two main sources on Sulla, Plutarch and Appian . For the meaning of the name, see Sulla (Cognomen) .

- ^ Plutarch, Sulla 1.

- ↑ Sallust, De bello Iugurthino 102-113.

- ↑ Velleius 2,12,5.

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 5.3.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 73.

- ^ Plutarch, Sulla 5.

- ^ Plutarch, Sulla 5.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 1.51.

- ↑ Valerius Maximus 9,7,1.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 1.57.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 1.57.

- ^ Wolfgang Kunkel with Roland Wittmann : State order and state practice of the Roman Republic. Second part. The magistrate . Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-33827-5 (by Wittmann completed edition of the work left unfinished by Kunkel). Pp. 654-659 (650).

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 1.59.

- ↑ Valerius Maximus , Facta et dicta memorabilia 9.2, Externe 3 ( German , Google Books).

- ↑ Memnon of Herakleia 22.9 .

- ↑ Plutarch , Sulla 24.4 , names 150,000 Italians and Romans killed in a single day. Axel Niebergall also considers the figure of 80,000 (given that Ephesus has a maximum population of 200,000) to be exaggerated: Many Italians had fled to Rhodes or Delos before Mithridates' invasion . Appian also only describes temple murders, not in private homes. Cf. Axel Niebergall: Local elites under Hellenistic rulers. In: Boris Dreyer, Peter Franz Mittag (eds.): Local elites and Hellenistic kings: between cooperation and confrontation. Heidelberg 2011, pp. 55–79, here: p. 59. Michael Rostovtzeff also speaks in his social and economic history of the Hellenistic world. Volume 2, Darmstadt 1998, p. 645 Doubts about the basis of this calculation.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 151.

- ^ Appian, Mithridateios 30.

- ↑ Appian, Mithridateios 38.

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 14.8.

- ↑ For an overview of the damage see Christian Habicht: Athens. The history of the city in Hellenistic times. Munich 1995, p. 307ff.

- ^ Appian, Mithridateios 56-58.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 1.79.

- ↑ Valerius Maximus 9.2.1–2 with Yan Thomas: Revenge on the forum. Family solidarity and criminal trial in Rome (1st century BC - 2nd century AD). In: Historical Anthropology. Volume 5 (1997), pp. 183-186. Prohibition in 97 BC Chr.

- ^ JS Reid: Human Sacrifices at Rome and other Notes on Roman Religion. In: The Journal of Roman Studies Volume 2 (1912), pp. 41-45.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 246f.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 1,98,459. In addition Heinz Bellen: Sulla's letter to the Interrex L. Valerius Flaccus. On the genesis of the Sullan dictatorship. In: Historia 24, 1975, pp. 555-569.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 1,98,460.

- ^ Wolfgang Kunkel , Roland Wittmann : State order and state practice of the Roman republic. Second section: The Magistratur (= Handbook of Classical Studies . Department 10, Part 3, Volume 2, Section 2). Munich 1995, p. 705.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 1,99,462.

- ^ Appian, Civil Wars 1,3,9.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 1,97,451f.

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 34.2.

- ↑ Holger Behr: The self-portrayal of Sulla. An aristocratic politician between personal leadership and solidarity. Frankfurt 1993, p. 149.

- ↑ Holger Behr: The self-portrayal of Sulla. An aristocratic politician between personal leadership and solidarity. Frankfurt am Main 1993, p. 102.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 265f.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 119.

- ↑ Holger Behr: The self-portrayal of Sulla. An aristocratic politician between personal leadership and solidarity. Frankfurt am Main 1993, p. 136.

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 34.1.

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 35.1.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 267.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 1,95,441.

- ^ Roland Wittmann: Res publica recuperata. Basics and objectives of the sole rule of L. Cornelius Sulla. In: Dieter Nörr , Dieter Simon (Hrsg.): Gedächtnisschrift für Wolfgang Kunkel. Frankfurt am Main 1984, pp. 563-582, here pp. 570 f. Herman Bengtson, however, judged the proscriptions differently. For him, the proscriptions had no legal basis, but were pure arbitrariness on the part of Sulla: Hermann Bengtson: Römische Geschichte: Republik und Kaiserzeit: Republik und Kaiserzeit bis 284 AD Munich 1985, p. 159.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 250f. The concrete title of the law has not been passed down, so that various assumptions have been made in research. In the most recent special study on proscriptions, the law was called lex Cornelia de hostibus rei publicae : François Hinard: Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine , Paris 1985, p. 75. Other researchers assume the name lex Cornelia de proscriptione : Karl Christ : Caesar: Approaching a dictator. Munich 1994, p. 30; Roland Wittmann: Res publica recuperata. Basics and objectives of the sole rule of L. Cornelius Sulla. In: Dieter Nörr, Dieter Simon (Hrsg.): Gedächtnisschrift für Wolfgang Kunkel. Frankfurt am Main 1984, pp. 563-582, here p. 571.

- ↑ Velleius 2.28.3 ; Plutarch, Sulla 31.7 . Karl Christ: Caesar: Approaching a dictator. Munich 1994, p. 31.

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 31.7.

- ↑ Valerius Maximus 9.2.1.

- ↑ Alfred Heuss : The Age of Revolution. In: Propylaea World History . Volume 4, Berlin 1963, pp. 175-316, here p. 225.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 117 f.

- ↑ Velleius 2,28,4.

- ^ Klaus Bringmann: History of the Roman Republic. From the beginning to Augustus. Munich 2002, p. 268.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 115.

- ^ Cicero, Pro Sex. Roscio Amerino .

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 31.5.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 258.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 283.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 127.

- ^ Theodora Hantos: Res publica constituta. The constitution of the dictator Sulla Stuttgart 1988, p. 52f.

- ^ Bernhard Linke: The Roman Republic from the Gracchen to Sulla. 2nd, reviewed and bibliographically updated edition. Darmstadt 2012, p. 133.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 280.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 125.

- ^ Theodora Hantos: Res publica constituta. The constitution of the dictator Sulla. Stuttgart 1988, p. 34.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 277.

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 33.4.

- ^ Bernhard Linke: The Roman Republic from the Gracchen to Sulla. 2nd, reviewed and bibliographically updated edition. Darmstadt 2012, p. 131.

- ^ Klaus Bringmann: History of the Roman Republic. From the beginning to Augustus. Munich 2002, p. 272.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 273.

- ^ Bernhard Linke: The Roman Republic from the Gracchen to Sulla. 2nd, reviewed and bibliographically updated edition. Darmstadt 2012, p. 128.

- ^ Wolfram Letzner: Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attempt a biography. Münster 2000, p. 300.

- ↑ Werner Dahlheim: The coup d'état of the consul Sulla and the Roman Italian policy of the eighties. In: Jochen Bleicken (Ed.): Colloquium on the occasion of the 80th birthday of Alfred Heuss. Kallmünz 1993, pp. 97-116, here p. 114.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 1,100,470.

- ↑ Werner Dahlheim: The coup d'état of the consul Sulla and the Roman Italian policy of the eighties. In: Jochen Bleicken (Ed.): Colloquium on the occasion of the 80th birthday of Alfred Heuss. Kallmünz 1993, pp. 97-116, here pp. 114f.

- ^ Helmuth Schneider: The emergence of the Roman military dictatorship. The crisis and decline of an ancient republic. Cologne 1977, p. 127.

- ^ Elisabeth Erdmann: The role of the army in the time from Marius to Caesar. Military and political problems of a professional army. Neustadt / Aisch 1972, p. 113.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 1.104.

- ^ Wolfgang Kunkel, Roland Wittmann: State order and state practice of the Roman republic. Second section: The Magistratur (= Handbook of Classical Studies. Department 10, Part 3, Volume 2, Section 2). Munich 1995, p. 711.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 134.

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 37 .

- ↑ Hans Volkmann: Sulla's March on Rome: The Decay of the Roman Republic. Munich 1958 (ND. Darmstadt 1969), p. 87.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, pp. 137f.

- ↑ Hans Volkmann: Sulla's March on Rome: The Decay of the Roman Republic. Munich 1958 (ND. Darmstadt 1969).

- ^ Christian Meier: Res publica amissa. A Study of the Constitution and History of the Late Roman Republic. 3rd edition, Frankfurt am Main 1997, p. 250.

- ^ Hermann Diehl: Sulla and his time in the judgment of Cicero. Hildesheim 1988, p. 97.

- ^ Suetonius, Caesar 77.

- ↑ Strabo 5,11,249.

- ↑ Seneca, De clementia 1, 12, 1-2.

- ↑ Plutarch, Sulla 33.1.

- ↑ Augustine, De civitate dei 3,27ff.

- ^ About the Sulla reception in modern times Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, pp. 167-194.

- ^ Theodor Mommsen: Roman history. Volume 2. 9th edition, Berlin 1903, p. 153.

- ^ Theodor Mommsen: Roman history. Volume 2. 9th edition, Berlin 1903, p. 367.

- ^ Leopold von Ranke: Weltgeschichte. Volume 2. 5th edition, Munich et al. 1922, p. 276.

- ^ Jérôme Carcopino: Sylla ou la monarchie manquée. Paris 1931.

- ^ Helmut Berve: Sulla (1931). In: Ders .: Formative forces of antiquity. Essays and lectures on Greek and Roman history. 2nd, greatly expanded edition, Munich 1966, pp. 375–395, here: p. 394.

- ^ Hugh Last, R. Gardner: Sulla. In: The Cambridge Ancient History. Volume 9. Cambridge 1982, pp. 261-312.

- ^ Wilhelm Weber: Roman history up to the fall of the world empire. In: Willy Andreas (ed.): The new Propylaea world history. Volume 1, Berlin 1940, pp. 273-372.

- ↑ Jochen Bleicken: History of the Roman Republic. 2nd edition, Munich 1982, p. 73.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 186.

- ^ François Hinard (Ed.): Dictatures. Paris 1988; François Hinard: Sylla. Paris 1985.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 196. Cf. the reviews by Theodora Hantos in Klio 86 (2004) 2, pp. 488-490; Herbert Heftner in: H-Soz-u-Kult, October 14, 2002, online

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 201.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 205.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 132.

- ^ Karl Christ: Sulla. A Roman career. 4th edition, Munich 2011, p. 209.

- ^ Theodora Hantos: Res publica constituta. The constitution of the dictator Sulla Stuttgart 1988.

- ↑ Arthur Keaveney: Sulla. The Last Republican. London 1982.

- ^ Bernhard Linke: The Roman Republic from the Gracchen to Sulla. 2nd, reviewed and bibliographically updated edition. Darmstadt 2012, pp. 136-138.

- ↑ Karen Piepenbrink : Sulla provides an overview of the history of reception . In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 961-970.

- ↑ On the portrait of Sulla, last Volker Michael Strocka : Portraits of Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department . Volume 110 (2003), pp. 7-36 ( PDF, 5.4 MB ); other: Caesar, Pompey, Sulla. Portraits of politicians from the late republic . In: Freiburg University Gazette. Volume 163 (2004), pp. 49-75, on Sulla pp. 66-75 ( PDF, 7.4 MB ).

- ↑ Volker Michael Strocka: Portraits of Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department. Volume 110 (2003), pp. 7-36, especially pp. 14-27. ( PDF, 5.4 MB )

- ↑ Volker Michael Strocka: Portraits of Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix . In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Roman Department. Volume 110 (2003), pp. 7–36, here: pp. 28–34 ( PDF, 5.4 MB ), which rejects all of these identifications.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sulla Felix, Lucius Cornelius |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Sylla; Cornelius Sulla Felix, Lucius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Roman politician and general |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 135 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 78 BC Chr. |