The Kongelige Grønlandske Handel

Den Kongelige Grønlandske Handel was a Danish state-owned company which, as a monopoly, traded with Greenland for 200 years and administered the settlements on the island. For more than 130 years it ruled the Danish colonies on Greenland through inspectors , Landsfogeder and Landshøvdinge .

As early as 1912 Den Kongelige Grønlandske Handel lost the task of political administration in Greenland. In 1950 their monopoly on trade in Greenlandic products was restricted. After Greenland's autonomy in 1979, Den Kongelige Grønlandske Handel initially became the property of the autonomous government and from 1985 onwards was divided into several state-owned companies.

Forerunners: Det Bergen Grønlandske Compagnie and Det almindelige Handelskompagni

Det Bergen Grønlandske Compagnie was a private trading company founded by Hans Egede , which existed from 1721 until its bankruptcy in 1727 and built the settlement Håbets Ø (near what later became Kangeq ) on Greenland . The surviving settlers from Håbets Ø later belonged to the founders of Godthåb, today's Nuuk . Another founding of the Bergen Grønlandske Compagnie was a whaling settlement on the island of Nipisat , which today belongs to Qeqqata Kommunia . This station was destroyed by the Dutch after a few years .

Det almindelige Handelskompagni (German: The general trading company) was also a private Danish-Norwegian trading company, which administered the trading branches of the kingdom in Greenland. It was founded on September 4, 1747 by royal decree, the first president was the privy councilor Christian August von Berkentin . Greenland was ruled by the Almindelige Handelskompagni from 1749 until its collapse in 1774. The company had a trade monopoly for the settlements, which was defended by warships under the Danebrog against the armed competition of the Dutch with their better and cheaper goods. The company's core business was buying seal skins , oil and other whaling products from local hunters and selling these goods in Europe. Since their trade monopoly was spatially limited to a fixed radius around their branches, the establishment of further settlements was in the interests of society. This resulted in a large number of settlements that still exist today on the west coast of Greenland. Det almindelige Handelskompagni got into trouble because of the takeover of the loss-making trade with Iceland and Finnmark and was taken over by the state in May 1774.

founding

On May 16, 1774, a royal resolution stipulated that Greenland's trade and shipping would in future be operated by a state-owned company. KGH considered this date to be its founding date. The settlements in Greenland previously managed by the Handelskompagni were transferred to the company, including foundations by missionaries from the Evangelical Lutheran Church and the Moravian Brethren . By another royal resolution of April 13, 1775, Den Kongelige Grønlandske Handel was also given the trade with the Faroe Islands . At the same time, another company was established to trade with Iceland and Finnmark . On March 18, 1776, the Danish crown prohibited any unauthorized trade with Greenland, giving KGH a monopoly that lasted until 1950. KGH's head office was Den Kongelige Grønlandske Handels Plads in Christianshavn , now part of Copenhagen , throughout its existence .

In 1781 both companies were merged to Den Kongelige Grønlandske, Islandske, Finmarkske og Færøske Handel og Fiskefangst and privatization was sought. Since no private interested parties could be found for the company, the Danish state had to keep the company going. State officials Christian Ludvig Stemann and Ove Høegh-Guldberg became executive directors . The company name was changed to Den Kongelige Grønlandske, Islandske, Finmarkske og Færøske Handel . The fact that the company's board of directors was granted direct access to the king is evidence of the great importance that was attached to the company.

Commercial activity

At first the KGH only had the monopoly for trading in the immediate vicinity of the trading stations and missions. But as early as 1776 the monopoly was extended to all trade in Greenland between the 60th and 73rd parallel . Between 1776 and 1782 123 ships were equipped for the Greenland voyage with capital from various donors . At that time, seven of the company's eight commanders came from the island of Föhr , which at that time belonged to Denmark and on which several seafaring schools were operated.

In connection with the bankruptcy of the Danish West India Company in 1776, between 1778 and 1783 - during the American War of Independence - 38 ships from Kongelige Grønlandske Handel and two ships from Kongelige Islandske, Finmarkske og Færøske Handel were sent to the Danish West Indies .

In 1782 the KGH established principles for trade with Greenland, which in essence lasted until 1950. As far as the purchase of Greenlandic products was concerned, the KGH had a great influence on the newly formed economic life in Greenland by setting the purchase prices. The price was set on the basis of political considerations and represented an attempt at sustainable economic activity. The KGH paid hunters all over Greenland uniform prices without taking their own transport costs into account. In doing so, the company wanted to ensure that hunting and the sale of the products to the KGH were also attractive for Greenlanders in the remote areas. The KGH also made policy with the setting of the sales prices for goods exported to Greenland. A surcharge for the transport and maintenance of the infrastructure in Greenland was included in the calculation. However, considerations were also made as to the extent to which a delivered product affects the productivity of the recipient in the long term. Weapons, lead, gunpowder, iron and steel were only given a small surcharge of 12 percent, as the use of these goods was in the interests of KGH. Coal and coal stoves were even subsidized so that the Greenlanders weren't forced to heat with the precious bubbler . A premium of 40 percent was calculated for luxury goods. As with purchases for export, the goods imported into Greenland were subject to unit prices, regardless of the cost of transportation to remote regions.

The company, trading as Den Kongelige Grønlandske, Islandske, Finmarkske og Færøske Handel since 1782, ceased trading with Iceland and Finnmark on January 1, 1790. Nevertheless, the KGH's business remained in deficit and the company stopped whaling and seal hunting in 1792. The whalers were sold and the largest Danish shipowner, Andreas Bodenhoff , was granted a license to sail in Greenland. After his death in 1794, it was transferred to his son of the same name, but on January 1, 1797, the company bought nine ships from the widow of the younger Bodenhoff, Giertrud Birgitte Rosted, and resumed traffic on its own.

In 1814 the Danish crown ceded Norway to Sweden in the Peace of Kiel . The former Norwegian colonies of Greenland, Faroe Islands and Iceland remained with Denmark. In the 20th century there was still a conflict with Norway, which insisted that, according to the Kiel Treaty, only economically used areas of Greenland were under Danish administration. Norway tried to set up a branch on the east coast of Greenland, but failed in court proceedings before the International Court of Justice in The Hague .

In 1856 the trade monopoly for the Faroe Islands expired, so that the KGH only benefited from trade with Greenland.

From 1871 to 1882 Hinrich Johannes Rink was director of the KGH. Under his direction, a fund was set up in 1872, into which the KGH paid one fifth of the prices paid for Greenlandic products. Part of the money was passed on to the local administrations, which used it to support the needy and administrative expenses. Another part was paid out to the hunters by the KGH through a bonus system in order to offer the most productive employees a financial incentive. This bonus system took into account not only the productivity shown in terms of the hunted prey, but also factors such as the existence of a family, the possession of dogs or umiaks and the use of economic support. In addition to the financial benefits, whether the hunter was allowed to participate in local self-government also depended on the classification in the bonus system.

The KGH employee structure towards the end of the 19th century was divided into three parts and characterized by inequality of opportunity. The management positions, that is the two inspectors and the heads of the administration in the individual districts, were always Danish. The lower positions, workers, men and servants, were always Greenlanders, often only employed as day laborers or temporarily. The middle tier was made up of skilled artisans, trained seafarers, and chiefs of trading posts. Both Danes and Greenlanders were represented here, but here too there was a tendency that more highly qualified and better paid employees were mostly Danes. In order to meet the need for qualified local employees, Greenlanders were brought to Denmark for training since the mid-19th century. From 1880 to 1896 there was Grønlænderhjemmet (German: Grönländerheim ) in Copenhagen, a training facility of the KGH, similar to a boarding school.

During the occupation of Denmark in World War II , shipping between Denmark and Greenland ceased. Since Greenland had only been connected to the rest of the world through Denmark for 200 years and all goods traffic was handled via Denmark, the people of Greenland were heavily dependent on the motherland. Led by the Danish Ambassador to the United States , Henrik Kauffmann , and Landsfowers Eske Brun and Aksel Svane , the economy of Greenland had to be reorganized and aligned with the United States. This succeeded, and KGH continued its business activities during the war years.

In 1950 the Greenland trade was restructured. The KGH retained its responsibility for the wholesale and retail trade, but other companies could acquire licenses for trade with Greenland. The monopoly on imports to Greenland was lifted, with the exception of certain goods such as alcohol and tobacco products, which were also subject to high tariffs. A number of tasks were entrusted to the KGH, such as the maintenance of the post office, banks, hotels, reindeer herding and Søndre Strømfjord Airport . In the following decades, new trade restrictions were repeatedly introduced, for example in October 1957 the KGH monopoly on tobacco, chocolate, sweets and malt, and in 1965 a special tax on sugar, coffee, tea, lemonades and mineral water. For KGH it was of particular importance that it increasingly had to face the competition. It was also able to survive by giving up its focus on retail and serving private companies in Greenland as a wholesaler. A number of corporate divisions were gradually outsourced to private entrepreneurs, from small businesses in remote locations to large manufacturing operations.

Since its inception, the United Nations has taken a very critical stance on colonialism . Denmark also had to report to the UN on its relationship with Greenland. Unlike typical colonial powers such as the United Kingdom and France , which gradually gave their colonies independence in the decades following World War II, Denmark sought to incorporate Greenland into the kingdom. In 1953 the Danish-Greenlandic colonial history ended.

The Kongelige Grønlandske Handel was separated from the Ministry of the Interior at the end of the colonial period and was given its own board of management, which included representatives of Greenland and Danish parliaments and authorities and Danish business associations. With the entry into force of the Danish Statute of Autonomy on May 1, 1979, Greenland was given full internal political autonomy with its own parliament and government. This had an impact on the KGH, as the Statute of Autonomy provided for its administration and responsibility for the Greenland economy to be transferred to the autonomous authority.

On January 1, 1985, several subsidiaries were spun off from KGH, which merged in 1990 to form Royal Greenland A / S :

- Kalaallit Tunisassiorfiat (KTU, food production);

- Grønlands Hjemmestyres Trawlervirksomhed (GHT, the state trawler fleet);

- Royal Greenland A / S, trade.

January 1st, 1986 is the founding date of KNI A / S (Kalaallit Niuerfiat), a conglomerate with a focus on trade and supply. In 1993, the KNI was split into three companies, the retail chain KNI Detail A / S (later Pisiffik ), the retail chain KNI Service A / S (later Pilersuisoq ) and the Royal Arctic Line A / S , a transport company that dispatches freight to and from to Greenland as well as intra-Greenland transport.

Administration of Greenland

From 1774 to 1908, the society was responsible for the political administration of the island in addition to the Greenland trade. It was carried out by the inspectors .

In 1782 the Society issued regulations regulating the relationship between Christian missionaries and traders. In it, rules of conduct for dealing with the Greenlanders were drawn up for the company's employees. Greenland was divided into a southern and a northern inspectorate. At the head of the administration of both provinces was a company inspector. The inspectorate North Greenland stretched from the 67th to the 72nd latitude and enclosed the districts Upernavik , Omenak , Jakobshavn , Christianshaab , Egedesminde and Godhavn . The first inspector was Johan Friedrich Schwabe . The South Greenland Inspectorate covered the part of Greenland south of the 67th parallel with the districts of Holsteinsborg , Sukkertoppen , Godthaab , Fiskenæsset , Frederikshaab and Julianehaab . Here was Bendt Olrik the first inspector.

The districts were named after their largest settlements, the colonies. The colonies handled economic affairs directly with the KGH in Copenhagen. Politically they were governed in Greenland, the heads of the colonies were officials who were subordinate to the inspectors.

The rules for the behavior of the European settlers and employees of the KGH and also for the missionaries had an economic background. At the end of the 18th century, the profit from whaling was already declining with the stocks of whales. The Greenland trade was still profitable because Greenland hunters sold the captured fur of seals and polar bears and the bubbling of the seals to the KGH.

There was concern that the contact of local hunters with Europeans could lead to their civilization and Europeanization and the loss of their ability and will to hunt. The trade in alcoholic beverages was strictly regulated, and the Greenlanders were not allowed to sell alcohol. This initially also applied to coffee and tobacco, but in 1837 the sale of luxury goods such as coffee, tea, sugar and grain was released to the Greenlanders.

A contemporary report from the late 19th century shows how justified the fear of negative effects of contact with Europeans was. In 1887 a travelogue was published describing the situation in Godthåb . In it, the indigenous population was described as poor and impoverished seal hunters who were no longer able to obtain the most important Greenlandic product, the seal bubble. The author attributed the impoverishment of the Greenlanders, which was particularly pronounced in Godthåb, to the fact that the longest contact with the Europeans had existed here. The local hunters indulged in the consumption of coffee and tobacco, which was imported by the KGH and had to be paid dearly. In order to be able to buy these goods, the Greenlanders even sold the seal skins they needed to make kayaks and clothing, and the meat and blubber for their own food.

In addition to targeted attempts to protect the original way of life of the Greenlanders from European influences, not only the missionaries but also the KGH took measures aimed at improving education (in the European sense) and medical care, which were financed by the KGH. In 1845, for example, two teachers' seminars were set up to train local primary school teachers, and Greenlanders were increasingly brought to Denmark for training. Also in 1845 the KGH hired a doctor to take care of the Greenlanders.

After a local self-government had already been introduced in Denmark in 1841 by local councils under the chairmanship of the pastor, local self-government at the district level was established on a trial basis in Greenland in 1857 and in 1862 permanently with the Forstanderskaberne . As in Denmark, the councils were headed by a pastor, here a missionary, and in second place was an employee of the KGH. Further members were Danish employees of the KGH and Greenlanders appointed for this office. The places of eliminated Greenlanders were filled again by the councils themselves, whereby bad hunters and impoverished Greenlanders could not be elected. The main task of the councils was to care for the poor, but they could use funds for the common good at their own discretion. A quarter of the price paid by the KGH for Greenlandic goods was available for this purpose, and a tax was levied on luxury goods such as coffee, sugar and bread. The unused money flowed into a bonus system for the Greenlandic hunters.

A significant aspect was the police and judiciary. In principle, people refrained from interfering in the internal affairs of the Greenlanders even in the early days of colonization. As a result, the KGH did not prosecute even the most serious crimes (by European standards) within the Greenlandic communities. There was no codified law in the sense of a catalog of punishments that would have determined the level of punishment for individual offenses, and there were neither police nor detention centers to prosecute lawbreakers and imprison them. The situation is different for the criminal offenses committed by Danes, who were also subject to prosecution in Greenland under Danish law. For Greenlanders who were in the service of the KGH, different regulations applied during colonial history. Since 1909, when the local council of Julianehåb asked the North Greenlandic inspector Jens Daugaard-Jensen to introduce prison sentences and a prison system, the KGH had known that the Greenlanders wanted a legal system. The KGH administration informed its inspectors in a letter that they now consider the Greenlanders to be mature enough for criminal reforms because of the desire they have expressed themselves. It was not until Daugaard-Jensen's successor, Harald Lindow , who wrote the first draft of a Greenland penal code, which, however, was not implemented.

The only exception was the activity of the local councils since 1857. Although they were not allowed to pronounce punishments, apart from minor offenses, they acted as an investigative body and had to submit their investigation results and a proposal for the punishment of the perpetrator to the KGH inspector. Their activity was limited to a few cases:

- Unauthorized use of or damage to third-party property such as weapons and tools, withholding someone else's hunting prey without payment and taking away driftwood that someone else has already pulled over the high water mark;

- simple theft and disobedience to the authorities;

- Homicides, including neonaticide .

All other crimes were prosecuted by the Greenlanders themselves under their traditional law.

On May 27, 1908, after years of disputes, which were mainly conducted among Danes, a new law on the administration of the Greenlandic colonies came into force. This separated trade and colonial administration, and administration was transferred to the Styrelsen af Kolonierne i Grønland department in the Danish Ministry of the Interior . Den Kongelige Grønlandske Handel initially remained independent as a state-owned trading company, but in 1912 its head was subordinated to Styrelsen af Kolonierne i Grønland. The inspectors continued to oversee the business of KGH in Greenland.

Monetary affairs

Greenland society knew no money . Since the early days of whaling, business with the Greenlanders had been barter, in which the Greenlanders received an equivalent in coveted goods such as weapons, ammunition and clothing for their skins, bubblers or whale bones. There were no uniform prices on the island, and the Greenlanders were often clearly overreached in these deals. The first two inspectors at KGH, Johan Friedrich Schwabe and Bendt Olrik , put an end to these machinations. They introduced uniform vessels for measuring the blubber and published lists of exchange rates every year. The basis was the bubbler, in terms of weight or volume. For example, a pound of gunpowder was worth two pounds of bubbler. The principle of a single price for the whole island was maintained by KGH until the end.

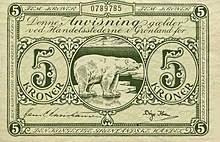

The barter trade was cumbersome in spite of the uniformly fixed prices, often remaining amounts remained open. There was a growing need for a medium that would simplify billing and allow the proceeds of a sale to be retained. Fiat money was introduced in Greenland without the Greenlanders getting to know early forms such as primitive money . The beginning was made in 1801 with handwritten notes that were destroyed upon return, from 1803 printed banknotes followed. In addition, tokens were issued by the KGH and other companies , in 1894 and 1905 also by the KGH.

Banknotes

The first Greenland banknotes were written playing cards issued by Inspector Claus Bendeke in Godhavn in 1801 to pay for the whaling. They had a value from six skilling to 10 rigsdaler and were destroyed when they were returned. From 1803 printed banknotes followed, which were only valid in Julianehaab , and from 1804 issues for the whole island. The design of the banknotes was repeatedly changed in the 19th century. In 1926, the circulating banknotes were withdrawn and in their place those issued by the Greenland Administration Grønlands Styrelse , which had been printed in Denmark. With the incorporation of Greenland into the Kingdom of Denmark, KGH again received the sole right to issue Greenlandic banknotes and coins, which were only legal tender there. In 1967 the Greenlandic banknotes and coins were withdrawn, since then the Danish krone has been the only valid means of payment.

The acceptance of banknotes as a means of payment was extremely low, and they did not have to be accepted by the Greenlanders if they preferred to exchange them for goods. They played no role in the dealings between the Greenlanders. There were repeated concerned voices from senior Danish officials concerned about the way Greenlanders were handling the banknotes. In the course of the development of Greenlandic self-government, the concern was expressed by Danes that the mere existence of Greenlandic banknotes of their own must be a reminder of the colonial administration for the Greenlanders. Others disagreed, arguing that the Greenlanders also saw banknotes as practical, regardless of who issued them. The Greenlandic politician Hans Lynge said during a debate in Grønlands Landsråd in 1961 that, as a proponent of Danish banknotes, he could understand if people want to see money with motifs from their own country. In fact, the representations on the KGH banknotes circulating in Greenland rarely had any reference to the island, and this was limited to stereotypical representations of "exotic" animals , as with colonial money in other countries .

In 1967 the Danish krone became legal tender in Greenland, also in response to the problem of the lack of Greenland coins for vending machines. Until then, banknotes were in circulation that named Den Kongelige Grønlandske Handel as the issuer on the edge .

- Banknotes from Den Kongelige Grønlandske Handel

1 crown from 1911 for the Holsteinsborg colony

Coins

The Royal Danish Grønlandske trade was 1,894 own coins from zinc out. They served as tokens for trading within the settlement in the newly established Ammassalik trading and mission station . There are tokens in the value levels 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 and 500 Øre . On the front they show within the inscription "ANGMAGSSALIK" a crown above a value in numbers. Except for two coins of 100 and 500 Øre, which are also available with the inscription "Am" on the back, they are only minted on one side. With editions of a maximum of 205 pieces, they are extremely rare. In 1905 another token for 500 Øre appeared in the same design, which was made of aluminum . There are aluminum specimens of the other value grades, but they were not put into circulation.

In 1957, the company minted a coin for a Danish crown made of aluminum bronze . The picture side showed the royal crown above the two coats of arms of Denmark and Greenland, with the inscription "DEN KONGELIGE GRØNLANDSKE HANDEL" and the year on the lower edge. The value side shows the number "1", underneath the currency indication "CROWN" and on the edge a surrounding wreath made of two branches with leaves and a flower each. In 1960 and 1964 the coin was struck again in cupronickel . In 1967 the Greenland coins were replaced by ordinary Danish kroner.

Directors

- Hartvig Marcus Frisch (1781–1816)

- ...

- Wilhelm August Graah (1831–1850)

- ...

- Christian Søren Marcus Olrik (1869–1870)

- Hinrich Johannes Rink (1871–1882)

- Hugo Egmont Hørring (1882–1889?)

- ...

- Carl Julius Peter Ryberg (1902–1912) and Oskar Wesche (1908–1912?)

- Jens Daugaard-Jensen (1912–1938)

- ...

- Anthon Wilhelm Nielsen (1951? –1956)

- Hans C. Christiansen (1956–1976)

- Jens Fynbo (1977-1981)

- Aage Chemnitz (1981–1985)

See also

literature

- Jan I. Faltings: Föhrer Greenland trip in the 18th and 19th centuries (= series of publications of the Dr.-Carl-Häberlin-Friesen-Museum (new series), volume 25) . Quedens, Wittdün auf Amrum 2011, ISBN 978-3-924422-95-0 ;

- Erik Gøbel: Danske oversøiske trading partner in the 17th and 18th annual speeches. En forskningsoversigt . In: Fortid og Nutid 1979-1980 , Volume 28, No. 4, pp. 535-569, ISSN 0106-4797 ;

- Søren Rud: Colonialism in Greenland. Tradition, Governance and Legacy . Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, Switzerland 2017, ISBN 978-3-319-46157-1 ;

- Axel Kjær Sørensen: Denmark-Greenland in the twentieth Century (= Meddelelser om Grønland, Man and Society 34) . Danish Polar Center, Copenhagen 2006, ISBN 978-87-90369-89-7 ;

- Aage V. Strøm Tejsen: The History of the Royal Greenland Trade Department . In: Polar Record , Volume 18, No. 116, 1977, pp. 451-474, doi : 10.1017 / s0032247400000942 .

Web links

- KNI's history - Trading in Greenland for centuries , website of KNI A / S , successor company as a conglomerate, especially trading;

- History , website of the Royal Arctic Line , successor company for sea transport, including shipping company and operation of ports (since 1992);

- Our Legacy , website of Royal Greenland A / S , successor company for fishing and processing of seafood .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Aage V. Strøm Tejsen: The History of the Royal Greenland Trade Department , S. 452nd

- ↑ Erik Gobel: Danske oversøiske handelskompagnier i 17 og 18 århundrede , pp 559-560.

- ^ A b c d e Aage V. Strøm Tejsen: The History of the Royal Greenland Trade Department , pp. 454–456.

- ↑ Erk Roeloffs: Whaling. A lucrative business only for officers . In: Der Insel-Bote , September 10, 2013, accessed on December 23, 2018.

- ↑ Erik Gøbel: Danske oversøiske handelskompagnier i 17th and 18th århundrede , p. 540.

- ^ A b Axel Kjær Sørensen: Denmark-Greenland in the twentieth Century , pp. 15-19.

- ^ A b c d e Aage V. Strøm Tejsen: The History of the Royal Greenland Trade Department , pp. 456–458.

- ^ A b Aage V. Strøm Tejsen: The History of the Royal Greenland Trade Department , pp. 459-460.

- ↑ Søren Rud: Colonialism in Greenland , pp. 44–49.

- ^ Søren Rud: Colonialism in Greenland , pp. 63–66.

- ↑ Aage V. Strøm Tejsen: The History of the Royal Greenland Trade Department , pp 464-466.

- ^ Søren Rud: Colonialism in Greenland , p. 123.

- ↑ Aage V. Strøm Tejsen: The History of the Royal Greenland Trade Department , pp 466-467.

- ↑ Axel Kjær Sørensen: Denmark-Greenland in the twentieth Century , pp. 108-110.

- ↑ Axel Kjær Sørensen: Denmark-Greenland in the twentieth Century , pp. 111-112.

- ↑ a b Axel Kjær Sørensen: Denmark-Greenland in the twentieth Century , pp. 157-163.

- ^ A b Søren Rud: Colonialism in Greenland , pp. 36–37, pp. 56–59.

- ↑ a b c d Axel Kjær Sørensen: Denmark-Greenland in the twentieth Century , pp. 11-15.

- ^ Gustav Frederik Holm and Vilhelm Garde : Den danske Konebaads-Ekspedition til Grønlands Østkyst. Populært beskreven . Forlagsbureauet, Copenhagen 1887, digitized . Quoted from: Søren Rud: Colonialism in Greenland , pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Søren Rud: Colonialism in Greenland , pp. 97-98.

- ^ Søren Rud: Colonialism in Greenland , pp. 103-105.

- ↑ Axel Kjær Sørensen: Denmark-Greenland in the twentieth Century , pp. 24-27.

- ^ A b c Anders R. Sørensen: Penge og national identitet i Grønland. Et blik på den grønlandske pengehistorie . In: Birgit Kleist Pedersen et al. (Ed.): Grønlandsk kultur- og samfundsforskning 2010-12 . Forlaget Atuagkat, Nuuk 2012, ISBN 978-87-92554-41-3 , pp. 129-146.

- ↑ Colin R. Bruce, George S. Cuhaj and Merna Dudley (eds.): Standard Catalog of World Coins 1801-1900. 5th edition . Krause Publications, Iola, WI 2012, ISBN 978-0-89689-373-3 , p. 504.

- ↑ a b George S. Cuhaj (ed.): 2013 Standard Catalog of World Coins. 1901-2000. 40th edition . Krause Publications, Iola, WI 2012, ISBN 978-1-4402-2962-6 , pp. 1012-1013.