Dresden fortifications

The Dresdner fortifications were first documented in 1299 and grew with the city to the softening of Dresden at the beginning of the 19th century.

Since November 2019 the State Palaces, Castles and Gardens of Saxony gGmbH has been presenting the history of the fortifications in a multimedia and immersive show under the name of Fortress Xperience in the Museum fortress Dresden .

location

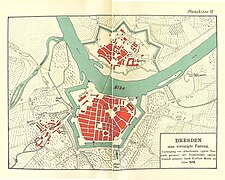

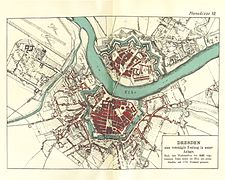

The Dresden Fortress ringed the inner old town . In its most recent state of development, its facilities extended in the east along today's St. Petersburger Strasse and in the south roughly along today's Dr.-Külz-Ring. The names of the streets "An der Mauer" and "Wallstraße", which run south and west of the Altmarkt respectively, refer to the fortifications that used to be adjacent to them. The course of the fortress ring is easy to understand in the north-west and north, as some of the buildings here on the Zwinger and in the form of the Brühl Terrace and the Bärenzwinger have been preserved.

Medieval fortification

The medieval city wall was first mentioned on August 17, 1299 in a document from the then Dresden city lord Friedrich the Little . It can be assumed that they existed around a century beforehand. At the time the city was founded, a palisade fortification is assumed, archaeological findings suggest that the stone city fortifications were built in the last quarter of the 12th century. On January 21, 1216, a certificate for the Altzella monastery was issued in the civitas Dresden by the margrave Dietrich the oppressed , which is a clear indication of a town with a town fortification at that time.

The city wall was built at the time of the rule of the Meissen Margraves Friedrich des Strengen (1349-1381, †) and Balthasar von Wettin (1354-1382, Chemnitz division ) from 1359-1370 with the help of sovereign money grants and the transfer of the surpluses of the salt trade from the sovereign to the council of Dresden further expanded and strengthened. At the time of the Hussite Wars , a second, low front wall was built in 1427, which also resulted in a kennel . These buildings were continued around the middle of the 15th century. At that time bastion towers were built on the walls and 15 wall towers on the Zwinger. A wooden walkway was laid out on part of the wall. The guns were stored in so-called rifle houses in the Zwinger. There were also shooting ranges for crossbow and rifle shooters . Deer were kept in the castle moat. The moat was in front of the kennel wall and was fed by the Kaitzbach .

The city wall was divided into four (sometimes five) quarters in case of defense.

A wooden city model, which was made by the Dutchman Max Stam at the time of Duke George the Bearded in 1521 and which showed the state of the city wall before it was repaired from 1519, was kept in the Green Vault until it was destroyed . There is a replica in the Dresden City Museum .

The first city gates

Entrance into the city was possible through five city gates. The gates were the Elbtor (or Brückentor, Altdresdnisches Tor), the Seetor , the Wilsche Tor (or Wilsdruffer Tor) and the Frauentor as well as the Kleine Kreuzpforte . The Elbtor was in the north at the exit of the Schloßstraße in front of the Elbbrücke , the later Augustusbrücke . In 1407 it was first mentioned as "Elbisches Tor", in 1455 as "Wasserthor" and in 1458 as "Brückenthor". Melchior Trost expanded it in 1553. It was demolished in 1738 when the Schloßplatz was laid out. The sea gate in the south of the city was first mentioned in 1403, it was at the exit of the Seegasse and was walled up in 1550, the wall tower was converted into a prison by Melchior Trost. In the years 1747/1748 it was reopened and according to plans by Johann Georg Maximilian von Fürstenhoff , the illegitimate son of Johann Georg III. , remodeled, in 1821 it was demolished. The Wilsche Tor was the western city gate at the exit of Wilischen Gasse. First mentioned in 1391, it was expanded at the beginning of the 15th century. Caspar Voigt von Wierandt expanded it in 1548 when the fortress was built. Because of the dilapidation, Paul Buchner and Hans Irmisch carried out major renovations after 1568 , such as the construction of a second floor with a roof hood and tower button. The Wilsche Tor was demolished in 1811. The Frauentor was the easternmost city gate in the Middle Ages, it was mentioned in 1297 and was located at the end of the small Frauengasse. It established the connection to the suburban settlements and to the Frauenkirche . After the settlements were incorporated into the city in 1529, the gate lost its function and was demolished in 1548 along with the city wall, which still separated the suburbs from the city. At the women's gate there was a cage, the so-called fool's house , in which drunkards were displayed.

The small Kreuzpforte was a small city gate that was first mentioned in 1370. It was at the end of Kreuzgasse, which later became Kreuzstrasse. In 1592 it was walled up.

First extension of the city fortifications

In the years 1519 to 1529, the settlements on the Elbe and the Frauenkirche were included with the first expansion of the city fortifications; this was done on the orders of Duke George the Bearded . This "Newe City" was protected by a wall. The old city fortifications remained at this point for the time being. The Rampisches Tor was built as a new gate in 1530. It replaced the Frauentor as the eastern city gate. Its location was roughly at the later Kurländer Palais . The name of the gate and the leading Rampischen Gasse derives from the village of Ranvoltitz , which was abandoned in the 15th century . In addition to the inclusion of the suburban settlements , the remaining sections of the city wall were reinforced on the outside by means of earthworks and external works.

With the invention of gunpowder in the 14th century, the way for cannons was paved. While the rule of “the higher the wall, the safer” applied in fortress construction up to now, there was a rethinking in the direction of “The more massive the fortification, the safer.” Soil gained importance as a building material for fortifications, as it dampens the momentum of the storeys (see plastic collision ).

Redesign by the first Albertine electors

Duke Moritz , who had risen to one of the most important sovereigns within the Holy Roman Empire in the Wittenberg surrender after becoming elector , had the medieval fortifications expanded into a modern fortification system. He got to know the models for the Italian-Dutch defense system in Ghent and Antwerp .

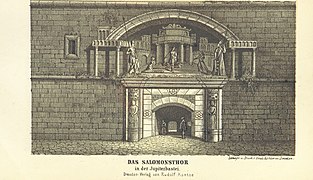

The plans for the expansion came from the fortress builder Caspar Voigt von Wierandt , Melchior Trost was the chief stonemason. The work began in 1546 and continued after the Schmalkaldic War . Around 900 workers are said to have been employed in the fortress construction around 1550. As early as 1548, the old city wall between the city and the eastern suburbs was torn down. The Rampische Tor was demolished in 1552 when the brick and Salomon doors were built. The Elbtor was expanded, the Georgentor connected to it and the sea gate were walled up. The brick gate (or ship gate) was on the Elbe side of the fortress wall at the northeast corner of the later art academy . When the city fortifications were subsequently expanded, it was built over. It can still be seen in the Museum fortress Dresden under the Brühl Terrace . The Salomonistor, built by Caspar Voigt von Wierandt, roughly replaced the cross gate.

When Elector Moritz died in 1553, his brother and successor August had a memorial erected for him, the so-called Moritzmonument , at the place where the fortress was built at that time .

In 1568 the work was continued by Rochus zu Lynar and Paul Buchner . From 1589 to 1591, the last section of the new complex, the “new vestibule or mountain at the brick gate”, was completed, which later became the Brühl Terrace. In connection with the completion of the Pirnaischer Tor in 1591 in the east of the complex, the Salomonistor and the brick gate were replaced and walled over in 1553. The Pirnaische Tor was built by Paul Buchner , it was at the end of the Landhausstrasse. On the gate there was an equestrian statue of Elector Christian I. The statue was created by Andreas Walther III . It was destroyed in 1760. On the upper floor was the simple building prisoner church , it was the church of the fortress building prisoners. It goes back to a wooden house of prayer on the Salominis Bastion , which August the Strong had built in 1711. Fortress builder Johann Gottfried Lohse rebuilt it in 1780 above the Pirnaischer Tor. It was renewed in 1792. Johann Christian Hasche was the preacher . The Pirna Gate was demolished in 1820, the church in 1824.

Names of the fortifications

The bastions of the new fortress had names - from east to west they were: Jungfernbastei with upper and lower Ritterberg, Hasenberg (or Zeughausberg), Salomonisberg , Seeberg , Wilscher Berg , tree nursery with kennel ditch and fireworks area . The neighboring flanks of the tree nursery and the fireworks square, at the location of the later opera house, were called the two monks , the area between the fireworks square and the Münzberg bridge and the protrusion of the later Brühlsche Terrasse (location of the Rietschelden monument ) were called the platform . A monument on Brühl's Terrace by Vinzenz Wanitschke from 1990 commemorates the bastions .

On the orders of Augustus the Strong in 1721, the names of the bastions were changed to Roman gods. The maiden bastion was called Venus , Hasenberg Mars , Salomonisberg Jupiter , Seeberg Merkur , Wilsdruffer Bastion Saturn , Luna Tree Nursery and Sol fireworks site .

The former Mercury Bastion around 1873, painting by Julius von Leypold

Inclusion of old Dresden

After the unification of Altendresden with Dresden on March 29, 1549, the expansion of the fortifications for Altendresden, begun in 1546, got stuck. The fortifications were not expanded until 1632.

During the entire 18th century, the Altendresdner and Neustädter fortifications were expanded several times, for example 1704 to 1706, 1732, 1740, 1757 and 1796.

The bastions were numbered consecutively from east to west with Roman numerals from I to VI. The protective wall between the Elbe and the moat was called “Beyer” but the terms “Beierwall”, “Bär” and “Bartadeau” were also used.

Softening

After the city fortifications had lost their military value in the middle of the 18th century, Dresden was, with a few exceptions, decongested at the beginning of the 19th century.

For urban planning reasons and to gain building land, breaches were made in the old town's fortifications as early as the first half of the 18th century. During the construction of the Zwinger, parts of the Luna bastion and in 1738 during the construction of the Catholic Court Church and the Schloßplatz, parts of the wall were removed. The first plans for the complete decongestion were made in 1760 by Oberlandesbaumeister Julius Heinrich Schwarze . However, these plans were rejected for military reasons. After the bombing of Dresden by the Prussians in the Seven Years' War , the Bavarian court architect François de Cuvilliés drew up plans to completely loosen it in 1762 , but these plans could not be realized for financial reasons.

In 1809, probably at the instigation of Napoleon I , the demolition of the fortifications began. About 1000 workers broke off the plants from November 20th. The work in the new town went quickly, as the walls belonged to the town. In the old town, some of the ramparts were privately owned and gardens were laid out. In April 1812 the work was stopped and in 1813 a new plant was even built. On the orders of the Russian governor Nikolai Grigorjewitsch Repnin-Volkonski , in 1814 Gottlob Friedrich Thormeyer laid out a flight of stairs from Schloßplatz to Brühl's terrace, which was then made accessible to the public.

In April 1817, the dismantling work was continued under a "demolition commission", which Thormeyer also belonged to. The softening was completed by 1829/1830.

From an urban and economic point of view, this decision was necessary for Dresden's growth during the industrial revolution .

Preserved parts of the fortification

The best-known part of the fortification that has been preserved is the Brühl Terrace, under which the Dresden Fortress Museum is located. Nearby is the Bärenzwinger , part of the Venus Bastion, which has been used as a student club since the late 1960s . Parts of the Luna bastion have been preserved at the kennel. Parts of the Dresden city wall can also be seen in the basement of the Gewandhaus (Ringstrasse 1). In the palace garden , at the Japanese Palace , parts of Bastion VI of the Neustadt fortifications have been preserved.

The parts of the fortification located between the Elbe and the old town are integrated into the city's flood protection . When the Elbe floods, the gates under the Brühl Terrace are sealed off by sheet piling. As a result, the Neumarkt area around the Frauenkirche is protected from surface water up to 9.24 meters water level. The Elbe reaches the fortification walls from a water level of about 5.20 meters.

With the Gasse An der Mauer , Wallstraße and Glacisstraße , three more streets in Dresden are named after parts of the fortifications.

literature

- Stadtlexikon Dresden A-Z . Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1995, ISBN 3-364-00300-9 .

- Eva Papke: Dresden Fortress. From the history of Dresden's city fortifications . 2., revised. Ed., Sandstein-Verlag, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-930382-12-5 .

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ CDSR 2/5 No. 14 of August 17, 1299 : Praedictos articulos ad nullos alios extendi volumus, nisi ad cives nostros infra muros civitatis nostrae Dresden et septa residentes.

- ↑ CDSR 1 / A / 3, No. 217 of January 21, 1216 : Acta sunt hec anno ab incarnatione domini nostri Iesu Christi millesimo ducentesimo XVI., Indictione V., XII. cal. febr. in civitate nostra Dresden ; feliciter.

- ↑ Edith Ennen : The European city of the Middle Ages. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1972, ISBN 3-525-01308-6 , p. 98.

- ↑ CDSR 2/5, No. 58 from 1359 to 1370 : Sovereign money grants for the fortifications of the Dresden citizens. (July 24, 1359, February 25, 1361, July 19, 1363, September 12, 1365, January 2, 1366, March 12, 1367 and January 4, 1370) and CDSR 2/5 No. 59 of July 15, 1361 : The Margraves Friedrich der Strenge and Balthasar entrusted the town with the salt trade with the stipulation that the surpluses resulting after deduction of the administrative costs should be used for fortifying the town.

- ↑ The city model. Leaflet of the state capital Dresden from November 2009 : The first city model of Dresden was built from wood by the Dutchman Max Stam in the 16th century.

- ^ Eva Papke: Dresden Fortress. From the history of Dresden's city fortifications . 2nd edition Dresden 2007, Fig. 6 after p. 12: City view of Dresden before 1519, view from the south, colored drawing based on a wooden model from 1521.