Farleigh Hungerford Castle

Farleigh Hungerford Castle , also Farleigh Castle , or Farley Castle , a ruined castle on the estate Farleigh Hungerford in the English county of Somerset . The castle was built in two phases: The main castle was Thomas Hungerford , of his fortune as governor of John of Gaunt made, built from 1377 to 1383. The castle was built as a fort - at that time already a somewhat traditional design - in place of an earlier manor house over the River Frome . A deer park was created next to the castle, which necessitated the demolition of an entire village. His son, Walter Hungerford , a successful knight and courtier at the royal court of Henry V , became rich in the course of the Hundred Years War with France and had the castle extended by a bailey , which also included the local parish church. After Walter Hungerford's death in 1449, the great castle was richly furnished and the castle chapel was decorated with frescoes .

Farleigh Hungerford Castle remained largely in the hands of the Hungerford family for the next two centuries , with the exception of two periods during the Wars of the Roses , when the castle was held by the Crown and after the indictment and conviction of some family members. When the English Civil War broke out in 1642, the castle, modernized according to the latest fashion in the Tudor and Stuart styles, belonged to Edward Hungerford . He supported the parliamentarians and became one of their leaders in Wiltshire . In 1643 Farleigh Hungerford Castle was conquered by the Royalists but in 1645, towards the end of the conflict, it was retaken by the Parliamentarists without a fight. It escaped after the war, grinding , unlike many other castles in southwest England.

The last member of the Hungerford family to own the castle was another Sir Edward Hungerford , who inherited it in 1657. But his gambling addiction and dissolute lifestyle forced him to sell the property in 1686. In the 18th century none of the owners lived in the castle and it slowly fell into disrepair. It was bought by the Houlton family in 1730 and most of it was demolished to reuse the building materials, e.g. B. for the construction of the country house Farleigh House . The interest of historical researchers and tourists in the remaining castle ruins increased in the 18th and 19th centuries. The castle chapel was repaired in 1779 and, including its frescoes rediscovered on its walls in 1844 and some rare humanizing lead coffins from the mid-17th century, has since served as a museum for curiosities. In 1915 Farleigh Hungerford Castle was sold to the Office of Works and a much-discussed renovation program began. Today the castle ruins belong to English Heritage , which they have listed as a historical building of the first degree. It is also considered a Scheduled Monument .

history

11th to 14th centuries

After the Norman conquest of England , William the Conqueror gave the manor of Ferlege in Somerset to Roger de Courcelles . The name "Ferlege" is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name Faern-laega , which means "ferny pasture" in German and later became "Farleigh". William Rufus then gave the manor to Hugh de Montfort , who renamed it Farleigh Montfort . The manorial rule then went into the first years of the reign of King Edward III. from the Montfort family to the Bartholomew de Bunghersh family .

Sir Thomas Hungerford bought the property from the Bunghersh family in 1369 for £ 733. From 1385 the manor was named "Farley Hungerford" after its owner. Sir Thomas Hungerford was a knight and courtier who became rich as chief governor to the mighty John of Gaunt and then as the first documented speaker of the House of Commons . Thomas Hungerford decided to make Farley Hungerford his headquarters and had a castle built there between 1377 and 1383. Unfortunately, he did not receive the required royal license to fortify his house (English: License to Crenellate) before construction of the castle began. So in 1383 he had to ask the king for forgiveness.

Thomas Hungerford's new castle included the existing manor house over the River Frome. Even if the castle was built on a low rocky spur, the hills to the north and west were higher, and it was not ideal from a purely defensive point of view. Contemporary castles had large, palatial residential towers and apartments for the most powerful nobles, such as B. Kenilworth Castle , which had been extended by Thomas Hungerford's Lord John of Gaunt, or there were smaller, French-influenced castle structures, such as the nearby Nunney Castle , which was built by one of the nouveau riche landowners, such as Thomas Hungerford. In contrast, Farley Hungerford Castle followed the tradition of castles as they were built in France since the beginning of the 13th century, where traditional buildings of a dirt mansion were enclosed in a four-sided outer wall, which was equipped with corner towers. This architectural style was still quite common at the end of the 14th century, albeit a bit old-fashioned.

The castle was built around an inner courtyard, which was later called the inner courtyard. It was surrounded by a curtain wall with a round tower at each corner and a gatehouse at the front . The northeast tower was larger than the others, possibly to serve as an additional defensive structure. Over time, each tower was given its own name: the northwest tower was called Hazelwell Tower , the northeast tower Redcap Tower and the southwest tower Lady Tower . From the castle, the terrain sloped steeply on most sides, on the south and west sides it was protected by a water-filled moat , the water of which came from a dam fed by a natural spring and with the moat by a pipe was connected. The gatehouse had twin towers and a drawbridge .

Opposite the entrance and running right through the courtyard was the knight's hall of the castle with a large vestibule and stairs to the first floor, where prestigious guests were entertained between carved screens and frescoes. The design of the great hall may have corresponded to that of John of Gaunt's great hall at Kenilworth Castle, but at least it was a powerful symbol of Thomas Hungerford's authority and social position. The kitchens, the bakery, the fountain and other utilities were located on the west side of the inner courtyard. On the east side there was the lord's parade bedroom and a number of other bedrooms for other guests. Behind the knight's hall was a smaller courtyard or garden. Thomas Hungerford seems to have had his new castle built in different phases; the curtain wall was erected first, then the towers were added.

A deer park was created around the castle; a park was a sign of great prestige, enabled Thomas Hungerford to hunt, ensured the castle was supplied with game meat, and was also a source of income. Most of the village of Wittenham had to be demolished to make way for the deer park, and the place then became a desert . A new parish church, consecrated to St. Leonhard, was built outside the castle by Thomas Hungerford after he had the old, simpler church from the 12th century demolished when the inner castle was built. Thomas Hungerford died in 1397 and was buried in the new Chapel of St. Anne, which was added to the north of the new church.

15th century

Walter Hungerford inherited Farleigh Hungerford Castle after the death of his mother Joan in 1412. Walter Hungerford's first political patron was John of Gaunt's son, King Henry IV and later became a close friend of King Henry's son, King Henry V Henry V made Walter Hungerford , like his father before him, in 1414 Speaker of the House of Commons. Walter Hungerford was successful, he became an expert in lancing . In 1415 he fought at the Battle of Azincourt in the Hundred Years War , was made Lord Steward of the Household and was an important figure in the government in the 1420s, having held the post of Lord High Treasurer and one of the guardians of the young King Henry VI. was. Although he had to pay a £ 3,000 ransom to the French after his son was captured in 1429, Walter Hungerford, now Baron Hungerford, amassed a sizable fortune from his various sources of income, including the right to 100 Mark (£ 66) a year from the city of Marlborough , Wells wool taxes and ransom money for French prisoners. So he was able to buy more land and accumulated 110 new manors and estates in his lifetime.

Between 1430 and 1445, Walter Hungerford had the castle expanded considerably. A bailey with its own towers and an additional gatehouse, which formed the entrance to the castle, was built on the south side of the bailey. These new defenses were not as strong as those of the inner castle and the eastern gatehouse was not provided with battlements at that time . A barbican was built as an extension of the old inner gatehouse. The new castle courtyard enclosed the parish church, which thus became the castle chapel; Walter Hungerford had a new parish church built in the village to replace it. He had the castle chapel decorated with a series of frescoes depicting scenes from the story of Saint George and the dragon . Saint George was Henry V's favorite saint and was associated with the prestigious Order of the Garter, to which Walter Hungerford belonged. A rectory was built next to the chapel. Walter Hungerford also legally linked the parishes of Farleigh in Somerset and Wittenham in Wiltshire, which were part of the deer park, thereby changing the boundaries of the two counties. As a village, Wittenham completely disappeared from the map.

Walter Hungerford left the castle to his son Robert Hungerford . Records from the castle show considerable luxury at the time, e.g. B. valuable picture knitwear up to 18.3 meters in length, silk bed linen, rich furs and silver bowls and other silver utensils. Robert Hungerford's eldest son, later Lord Moleyn , was captured by the French in the Battle of Castillon , defeated in 1453 towards the end of the Hundred Years War. The high ransom of over £ 10,000 financially ruined the family and Lord Moleyns did not return to England until 1459. By this time England had entered the period of civil war between the House of York and the House of Lancaster known as the Wars of the Roses . Lord Moleyns was a Lancastrian and fought against the Yorkists in 1460 and 1461, leading first to his exile and then to a treason charge as a result of which Farleigh Hungerford Castle was taken over by the Crown. Lord Moleyns was captured and executed in 1464, and his eldest son, Thomas , suffered the same fate in 1469.

The Yorkist King Edward IV lent Farleigh Hungerford Castle in 1462 to his brother Richard , the then Duke of Gloucester . Edward and Richard's brother George Plantagenet may have resided at the castle; his daughter Margaret was certainly born there. Richard became King of England in 1483 and lent the castle to John Howard , the Duke of Norfolk . Meanwhile, the executed Robert Hungerford's youngest son, Sir Walter , had become an avid supporter of Edward IV. Nevertheless, he joined the unsuccessful revolt of 1483 against Richard and ended up as a prisoner in the Tower of London . When Henry Tudor invaded England in 1485, Sir Walter Hungerford escaped from his guards and joined the invading Lancastrian army, where he fought side by side with Henry Tudor in the Battle of Bosworth . As the victorious, newly crowned King Henry VII, Henry Tudor gave Farleigh Hungerford Castle back to Walter Hungerford in 1486.

16th Century

Sir Walter Hungerford died in 1516, leaving Farleigh Hungerford Castle to his son, Sir Edward Hungerford . Edward Hungerford was a successful member of the court of King Henry VIII and died in 1522, leaving the castle to his second wife, Agnes . After Edward's death, however, it turned out that his widow was responsible for the death of her first husband, John Cotell : two of her servants had strangled him at Farleigh Hungerford Castle and then burned his body in the castle's oven to remove all evidence. Agnes appears to have been motivated by her desire for wealth that followed from marrying her second husband, Sir Edward Hungerford, but in 1523 she was hanged along with her two servants for murder in London.

Because of this execution, Edward Hungerford's son and another Walter inherited the castle instead of the widow. Walter Hungerford became a political supporter of Thomas Cromwell , the powerful Prime Minister of Henry VIII, and worked for him in the region. He fell out with his third wife, Elizabeth , after her father became one of his political supporters, and locked her in one of the castle's towers for several years. Elizabeth complained that while in captivity she had to starve to die and that there were multiple attempts to poison her. She was probably held captive in the northwest tower, even if the southwest tower was named after her Lady Tower . When Cromwell lost his power in 1540, Walter Hungerford also lost his and was executed for treason , witchcraft and homosexuality : Elizabeth was allowed to marry again, but the castle fell to the crown.

Walter Hungerford's son, also called Walter , bought the castle back from the Crown in 1554 for £ 5,000. Farleigh Hungerford Castle and the surrounding park were kept in good condition - in fact, the historian John Leland was able to praise its "beautiful and representative condition" on his visit, which was unusual at the time - but Walter Hungerford continued the modernization of the property, by adding modern Elizabethan style windows and improving the east wing of the inner castle, which then became the main residence for the owner's family. Walter Hungerford's second wife, Jane, was a Roman Catholic and the marriage could not withstand the turbulent religious policy of the later Tudor period; Jane went into exile. The only son of Walter and Jane Hungerford died young and after the death of Walter Hungerford in 1596 the castle fell to his brother, Sir '' Edward Hungerford ''.

17th century

Sir Edward Hungerford died in 1607, leaving Farleigh Hungerford Castle to his great-nephew, another Sir Edward Hungerford . This Edward Hungerford had the castle expanded and new windows built into the medieval buildings of the inner castle. In 1642 the English civil war broke out between the supporters of King Charles I and those of Parliament . A Reformist MP and Puritan , Edward Hungerford was an active supporter of Parliament and volunteered to lead his troops in the neighboring county of Wiltshire. Unfortunately, in early 1643 he got into trouble with Sir Edward Bayntun , a gentleman from Wiltshire. His military career during this conflict was unusual: he left various cities to the advancing royalist armies and fought on the losing side at the Battle of Roundway Down , but successfully captured Wardour Castle in 1643 .

Farleigh Hungerford Castle was captured by a royalist unit in 1643 after a successful campaign by royal troops through the south-west of England. The castle was taken without fighting by Colonel John Hungerford , a half-brother of Edward Hungerford, who then installed a garrison there, which lived by sacking the surrounding lands. Several parliamentarian attacks on Farleigh Hungerford Castle were launched in 1644, but the castle could not be retaken. In 1645 the royalist cause was close to military collapse; the parliamentarians began cleaning up the remaining royalist garrisons in the southwest, and on September 15 they reached the castle. Colonel Hungerford immediately surrendered the castle on good terms and Sir Edward Hungerford moved back into the undamaged castle in peace. So Farleigh Hungerford Castle escaped demolition by order of parliament, unlike many other castles in the region, we z. B. Nunney Castle .

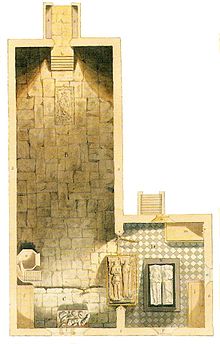

After Edward Hungerford's death in 1648, his half-brother Anthony Hungerford inherited the castle. The north chapel had been extensively renovated during this time on behalf of Edward Hungerford's widow Margaret ; she had the walls covered with images of saints, cherubim , clouds, ribbons, crowns and other heraldic symbols. This was part of a Church of the Holy Sepulcher for herself and her husband Edward and cost £ 1,100 (equivalent to £ 136,000 in 2009). During the renovation, the entrance to the northern chapel was almost blocked, making the tomb the focus of attention for every visitor and for all religious activities. A number of humanizing lead coffins, some with cast faces or death masks, were moved to the crypt in the mid to late 17th century. Four men, two women and two children were embalmed in the castle in this way, presumably including Edward and Margaret, as well as the last Edward Hungerford, his wife, son and daughter-in-law. Such lead coffins were extremely expensive at that time and were reserved for the wealthiest in society. Originally these lead coffins were built into the wood, but this outer jacket has now rotted away.

Anthony Hungerford bequeathed the castle and a considerable fortune to his son, another Edward Hungerford , in 1657. After his marriage, Edward Hungerford had an annual income of £ 8,000 (equivalent to £ 1.11 million today), making him a wealthy man. Edward Hungerford, however, lived dissolute and gave an immense sum of money to Charles II, who was living in exile, shortly before the Stuart Restoration . Later, in 1673, he maintained the royal court at Farleigh Hungerford Castle. Eduard Hungerford fell out with the king over the proposal that the Roman Catholic James II succeed Charles II on the English throne after his death, and after the discovery of the Rye House conspiracy in 1683 the castle was followed by royal officials Searched weapons stored there that could have been used in a possible revolt.

Edward Hungerford now led an extravagant life, including severe gambling addiction , and amassed about £ 40,000 in debt which in 1683 forced him to sell many of his Wiltshire estates. Over the next two years, Edward owed another £ 38,000 (equivalent to £ 5.27 million today) and in 1686 was finally forced to sell his remaining properties in south-west England as well. This included Farleigh Hungerford Castle, which was sold to Sir Henry Bayntun for £ 56,000 (equivalent to £ 7.75 million today) . Bayntun lived in the castle for a few years until he died in 1691.

18th to 20th century

From the 18th century Farleigh Hungerford Castle was increasingly left to decay. In 1702 it was sold to Hector Cooper , who lived in Trowbridge ; In 1730 it was passed on to the Houlton family, who had acquired the lands around the castle. The Houltons tore down the castle walls and sold the building blocks as well as the contents of the rooms. Some of the components, such as the marble floors, were reused in Longleat House or in the Houltons' new country home, the nearby Farleigh House , built in the 1730s . Further construction elements were used again in the houses in the village. At the end of the 1730s, the castle was in ruins and, even if the castle chapel was repaired and put to use in 1779, the north-west and north-east towers had collapsed by the end of 1797. The outer bailey became a farm and the rectory became a farmhouse. Farleigh Hungerford Castle deer park has been rededicated as a park for Farleigh House.

Historians' interest in the castle began as early as 1700 when Peter le Neve visited it and picked up some of the architectural details, but interest increased significantly in the 19th century. This was due in part to the work of the local curate , Reverend J. Jackson , who first had archaeological digs carried out on the castle grounds in the 1840s and discovered many of the foundations of the inner castle. Lead glass windows from Central Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries were built into the castle chapel, where the frescoes from the 15th century were rediscovered in 1844. The then owner, Colonel John Houlton , had the castle chapel converted into a museum for curiosities, where visitors could see armor for a small fee, as well as a pair of boots that should have belonged to Oliver Cromwell and other artifacts from the English Civil War, e.g. . B. Letters Cromwell wrote to the Hungerfords.

The foundations Jackson discovered during his excavations remained openly visible to visitors and a large number of tourists began to tour the ruins of the castle, including Napoleon III in 1846 . The lead coffins in the castle chapel were popular with tourists, even if they were badly damaged by visitors who also wanted to see the contents. The southwest tower, which was completely and thickly entwined with ivy , collapsed in 1842 after children from the area accidentally set fire to the vegetation that held the tower together at the time. During this time battlements were placed on the eastern gatehouse and thus changed the appearance of the original gable roof.

In 1891 the Houlton family sold most of Farleigh Hungerford Castle to Lord Donington , whose heir in turn sold it in 1907 to Wilfred Cairns, 4th Earl Cairns . Cairns gave the castle ruins to the Office of Works in 1915 ; At that time the entire building complex was overgrown with ivy. The Office of Works began a much-discussed restoration process, removing the ivy and repairing the walls. The result was criticized at the time by H. Avray Tipping because it "gave the castle the look of a new concrete building". Further excavations took place in 1924 as part of the project that received the castle as a tourist attraction. The last residents of the farmhouse left in 1959 when the last parts of the outer bailey were sold to the government and renovated. Efforts were made in 1931 and 1955 to preserve the frescoes in the castle chapel, but the treatment, which consisted of applying red wax , stained the paintings and caused great damage. The wax was removed in the 1970s. Further excavations around the castle chapel and the rectory followed in 1962 and 1968. English Heritage took over management of the castle ruins in 1983.

21st century

Today, most of Farleigh Hungerford Castle is in ruins. Only the foundations of most of the buildings and the empty outer walls of the south-west and south-east towers remain of the core castle. It is unusual for an English castle that more of the outer bailey has been preserved than the inner bailey. The restored eastern gatehouse is decorated with the Hungerford coat of arms and the initials of the first Sir Edward Hungerford to have them carved there between 1516 and 1522. The rectory remained intact; it has a floor space of 11.9 meters × 6.7 meters, two rooms on the ground floor and four on the upper floor.

In the St. Leonhard Chapel (castle chapel) you can still see the outlines of many medieval frescoes, including a painting of St. George with the dragon, which is still in good condition - historical researcher Simon Ruffey describes this work, one of only four such works that have survived in England as "remarkable". The graves of the Hungerfords from the end of the 17th century in the north chapel, dedicated to Saint Anne, are also intact. The humanizing lead coffins in the crypt that have survived to this day are of archaeological interest: even if they were numerous at the end of the 16th and 17th centuries, only a few have survived and Farleigh Hungerford Castle has what historian Charles Kightly calls “the best Collection “considered in the country.

The castle grounds are managed by English Heritage as a tourist attraction. It is a Scheduled Monument and English Heritage has listed it as a Grade I Historic Building.

Individual references and comments

- ^ A b Jame D. Mackenzie: The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure . Volume II. Macmillan, New York 1896. p. 57. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . S. 17. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b Dunning, pp. 57-58.

- ↑ It is impossible to compare prices and incomes from the 14th century with today's prices and incomes. As a comparison, however, it may be used that £ 733 is slightly more than the annual income of a typical nobleman of the time, such as B. Richard le Scrope, 1st Baron Scrope of Bolton , was whose estates brought in about £ 600 a year.

- ↑ a b Chris Given-Wilson: The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages . Routledge, London 1996. ISBN 978-0-203-44126-8 . P. 157. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 18. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ A b T. J. Miles, AD Saunders: (1975) The Chantry House at Farleigh Hungerford Castle in Medieval Archeology . 19 (1975). P. 165.

- ↑ a b License to crenellate Farleigh Hungerford Castle granted 1383 Nov 26 . Gatehouse Gazetteer. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c Anthony Emery: Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300-1500: Southern England . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5 . P. 533. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Stéphane W. Gondoin: Châteaux-Forts: Assiéger et Fortifier au Moyen Âge . Cheminements, Paris 2005. ISBN 978-2-84478-395-0 . P. 167. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, p. 167.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 5, 9. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 8-10. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ The name Hazelwell Tower comes from the nearby source, the name Redcap Tower from rumors about an evil spirit or possibly from the color of its original roof, the name Lady Tower from the misconception that Lady Elizabeth Hungerford was in the 1530s should have been imprisoned there.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 8–10, 24. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 11, 33. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ A b Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 7. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, p. 169.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 7, 10. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 33. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Oliver Hamilton Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2005. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8 . Pp. 190-191. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Oliver Hamilton Creighton, Robert Higham: Medieval Castles ( Memento of the original of March 18, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Shire Publications, Princes Risborough 2003. ISBN 978-0-7478-0546-5 . P. 57. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Joseph Bettey: From the Norman Conquest to the Reformation in M. Aston (Editor): Aspects of the Mediaeval Landscape of Somerset and Contributions to the Landscape History of the County . Taunton, UK: Somerset County Council, Taunton 1998. ISBN 978-0-86183-129-6 . P. 59. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 11, 18. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Oliver Hamilton Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2005. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8 . P. 124. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d T. J. Miles, AD Saunders: (1975) The Chantry House at Farleigh Hungerford Castle in Medieval Archeology . 19 (1975). P. 167.

- ↑ Ronald Wilcox: Excavations at Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset, 1973-6 in Proceedings of Somerset Archeology . 124 (1981). P. 87.

- ^ A b Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 13. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ A b Jame D. Mackenzie: The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure . Volume II. Macmillan, New York 1896. p. 58. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 19. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- ^ A b Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . S. 20. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Sir Walter Hungerford is occasionally credited with building the outer courtyard in the course of the capture of Karl von Valois, Duke of Orleans . Both Canon Jackson and Charles Kightly discuss this, with Jackson noting that it was Sir Richard Waller who captured the Duke in battle.

- ↑ John Edward Jackson: Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset in Proceedings of Somerset Archeology . Issue 1-3 (1851). P. 116.

- ↑ It is impossible to accurately compare 15th century prices and incomes with today's prices and incomes. As a comparison, however, £ 3,000 was about the equivalent of four times the annual income of a normal baron in the early 15th century. £ 66 was a little less than a tenth of that income.

- ^ Norman John Greville Pounds: The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a Social and Political History . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3 . S. 148. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 11. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Norman John Greville Pounds: The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a Social and Political History . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3 . P. 266. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . S. 5. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 12. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Oliver Hamilton Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2005. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8 . P. 125. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 11, 21. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 15. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Oliver Hamilton Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2005. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8 . P. 191. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 22. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 6. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ It is impossible to compare prices and incomes from the 14th century with today's prices and incomes. As a comparison, £ 10,000 is almost as much as the £ 12,000 it cost to build the great fortress Bolton Castle during that time, even if the latter costs were spread over a period of 20 years.

- ^ Ignatius Ingoldsby Murphy: Life of Colonel Daniel E. Hungerford . Case, Lockwood and Brainard, Hartford CT 1891. p. 5. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 22-23. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 23. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Marital Strife and Anthropoid Coffins at Farleigh Hungerford . English Heritage. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 24. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- ^ A b Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 25. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ It is difficult to compare 16th century prices and incomes with today's prices and incomes. Depending on which yardstick you use, £ 5,000 from 1554 can equate to £ 1.18 million (according to the sales price index) or £ 18.9 million (according to the average income index) in today's money. As a comparison, £ 5,000 was about 2.5 times the annual income of a wealthy knight like William Darrel , who owned 25 manors.

- ↑ Measuring Worth, Measuring Worth . Measuring Worth. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ↑ Hubert Hall: Society in the Elizabethan Age ( Memento of the original from March 18, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish 2003. ISBN 978-0-7661-3974-9 . P. 10. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 9, 25. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ John Edward Jackson: Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset in Proceedings of Somerset Archeology . Issue 1-3 (1851). Pp. 115-116.

- ↑ a b c d Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 26. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Bull, Henry. (1859) A History, Military and Municipal, of the Ancient Borough of Devizes . Longman, London 1859. p. 149. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 43. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 27. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Jame D. Mackenzie: The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure . Volume II. Macmillan, New York 1896. p. 62. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 14-15. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Simon Roffey: The Medieval Chantry Chapel: an Archeology . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2007. ISBN 978-1-84383-334-5 . Pp. 135-136. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ A b Sarah Tarlow: Ritual, Belief and the Dead in Early Modern Britain and Ireland . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2011. ISBN 978-0-521-76154-3 . P. 33. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ A b D. W. Hayton, Henry Lancaster: Sir Edward Hungerford in Eveline Cruickshanks, Stuart Handley (editor): The House of Commons: 1690-1715 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2002. ISBN 978-0-521-77221-1 . P. 437. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ A b Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 28. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e f Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 29. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- ^ A b John Edward Jackson: Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset in Proceedings of Somerset Archeology . Issue 1-3 (1851). Pp. 123-124.

- ↑ a b c d Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 30. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ↑ Kightly says that the castle was sold to the Houlton family in 1705 , Jackson says it was more like 1730.

- ^ A b c John Edward Jackson: Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset in Proceedings of Somerset Archeology . Issue 1-3 (1851). P. 117.

- ↑ John Edward Jackson: Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset in Proceedings of Somerset Archeology . Issue 1-3 (1851). P. 120.

- ^ Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . Pp. 12-13. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

- ^ GW Wade, JH Wade: Somerset . London: Methuen, London 1929. p. 134. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ↑ John Edward Jackson: Farleigh Hungerford Castle, Somerset in Proceedings of Somerset Archeology . Issue 1-3 (1851). P. 119.

- ↑ a b c d e f Charles Kightly: Farleigh Hungerford Castle . English Heritage, London 2006. ISBN 1-85074-997-3 . P. 31. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- ^ The Clifton Family . Amounderness.co.uk. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ^ A b Adrian Pettifer: English Castles: a Guide by Counties . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2002. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5 . P. 221. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ Priest's house, Farleigh Castle, Farleigh Hungerford . Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. ( Memento of the original from February 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ↑ Simon Roffey: The Medieval Chantry Chapel: an Archeology . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2007. ISBN 978-1-84383-334-5 . P. 73. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ Farleigh Hungerford Castle . National Monuments Record. English Heritage. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

Web links

Coordinates: 51 ° 19 ′ 0.1 ″ N , 2 ° 17 ′ 13.2 ″ W.