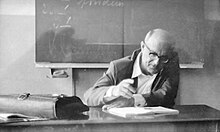

Fritz Rudolf Wüst

Fritz Rudolf Wüst (born September 19, 1912 in Glatz , Province of Silesia , † April 5, 1993 in Grassau ) was a German ancient historian whose focus was on Greek history from the 4th century BC. Chr. Lay. In the 1950s, he worked as a private lecturer and later as an associate professor at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich . He devoted himself primarily to practice-oriented teaching. However, he was denied greater recognition as a researcher of ancient history. During the Nazi era , he did not join the opportune currents of historical studies and received little support from the university administration or from his colleagues. These problems continued into the post-war period. In addition, Wüst now burdened membership in several Nazi organizations. In 1962 he ended his academic career prematurely, he remained in the school service.

Life

Origin and youth

Fritz Rudolf Wüst was born as the son of the engineer Fritz Wüst and his wife Frieda, née Hörrner, in Glatz, Silesia . His father died in the First World War ; family wealth was lost in the period of inflation . Wüst attended school in the Rheinpfalz - elementary school and Latin school in Bergzabern , the grammar school in Landau . Already during this time his talent for the ancient languages, especially ancient Greek , was evident . The mother, who had only very limited resources, could hardly support Wüst's training.

Role in National Socialism

After graduating from high school , Wüst studied classical philology , history and German at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich from the summer semester of 1932 . In 1933 he joined the SA and in 1937 - after the membership ban was relaxed - in the NSDAP . He was a member of the NS student union from July 1933 to March 1934.

During his studies, Wüst was dependent on scholarships for a long time . His main interest was in Greek history. First, he envisaged a school career. In the spring of 1936 he passed the first and in the spring of 1937 the second examination for the higher teaching post. He worked for a short time as a teacher at the Ludwigsgymnasium , then he was released from the Bavarian Ministry of Culture for scientific work. In this step, his academic teacher Walter Otto supported him , who suggested an academic career and habilitation to the student in the fourth semester . Otto also supported Wüst's application for a grant and certified his student that he was “one of the most scientifically promising among the current young generation in the field of ancient history”.

Wüst received his doctorate with “excellent success” as early as 1937 . The topic of his dissertation was The Macedonian and Athenian Politics in the Period from the Peace of Philocrates to the Halonnes Speech . The doctoral certificate was issued on February 24th and signed by Rector Leopold Kölbl and Dean Walther Wüst . In 1938 the study was published under the title Philip II of Macedonia and Greece in the years 346–338 in the publishing house CH Beck . In the summer semester of 1938, Wüst, who was still on leave from school, was given a teaching position for the first time. He led elementary Latin courses for several semesters in order to create financial reserves for the time he worked on his habilitation.

In the summer of 1939, shortly before the start of the war, Wüst volunteered to take part in a military exercise as an officer candidate . Soon after, the Wehrmacht drafted him . As the only son of a "war widow", however, he was only briefly deployed to the front . He then served in the Luftgaupostamt München 2 and in northern Germany, which prevented him from working on his habilitation. The deputy dean of the University, Franz Dirlmeier, failed in his attempt to have Wüst on leave for six months from military service.

Against all odds, Walter Otto died on November 1, 1941. For Wüst, he was not only an academic teacher, but also a close personal confidante, helper, father substitute and friend. Nevertheless, Wüst decided in 1942 to submit his habilitation thesis. This had - atypical for wartime - peace on the topic: Koine Eirene . The development of political expressions of Panhellenism in the period from the sixth century to the beginning of Hellenism . The reviewers Hermann Bengtson and Franz Dirlmeier received the work very positively. Then, however, problems arose in the habilitation process, which were probably due in part to Otto's absence as an accompanying academic teacher. In the "oral debate", the Germanist Erich Gierach criticized the post- doctoral candidate for lack of knowledge of the origins of the Romanian people. The classical philologist Rudolf Till criticized Wüst's teaching sample for having shown himself to be disinterested in the actual subject of Themistocles as a politician and for having wandered off in large parts. Dirlmeier later reported that the training sample was only accepted because Wüst's previous educational achievements and, above all, his many years of service in the Wehrmacht had been rated positively and the lack of young scientists had been taken into account. Even Helmut Berve was skeptical regarding Wüst's qualifying, but the procedure was otherwise been positive would not let just fail before the end. Karl Christ recognizes in this procedure an “act of grace” and a “second class habilitation”.

Wüst, who quickly became aware of the criticism, was deeply offended. He had great doubts about the progress of his academic career. He did not want to accept any extenuating circumstances and feared that he would not meet expectations later. As early as the day after the controversial teaching practice, he turned to Dean Dirlmeier with the request that the application for a lectureship should be postponed for the time being. The appointment to the student council on July 1, 1943 took place regardless of the continuous leave of absence Wüst from school service, which heightened his self-doubt. Wüst explained: “I also lack a teacher who is benevolent and yet absolutely critical by my side. I do not share Berve's scientific views. ”Despite everything, Dirlmeier submitted an application for a lectureship on August 30, 1943, which was approved. However , Wüst could no longer accept the certificate of appointment because it was destroyed in the fire of the university on July 13, 1944 (in an attack by 1,260 bombers of the 8th US Air Force on Munich).

Wüst was critical of the old German history of the Nazi era , which was under the leadership of Berves and Wilhelm Weber (1882–1948). He was thinking of pursuing a career in school and complained that there was no ancient historian to lean on, while more and more representatives of the Berve and Weber School were filling the available university positions.

post war period

Like many of his colleagues, Wüst was unable to continue teaching after the war. He was interned in Schleswig-Holstein until August 1945 and was relieved of his duties as a lecturer on December 12 of that year on the instructions of the military government . He was not allowed to enter the university buildings. That is why he initially stayed in Holstein, where he worked as an assistant in agriculture.

In addition to membership in the NSDAP, SA and the NS student union, Wüst was primarily burdened with letters of recommendation from the NS era. In 1936, Ernst Bergdolt , the head of the lecturing group, not only praised Wüst's scientific qualifications and character traits in a funding application, but also pointed out that the SA had given him a good assessment. Similar praise - in retrospect ambiguous - contained letters that Dirlmeier had formulated in 1940 in connection with his commitment to exempt Wüst from military service.

In a questionnaire on denazification, Wüst himself did not conceal his membership in Nazi organizations; He explained or excused her with a young age, a lack of leadership from his father, who had fallen at an early age, and his economic situation: “So, at the time of the 'takeover' by National Socialism, 20 years old, I had neither a political upbringing nor experience and management still had a direct relationship with politics. ”In the denazification process, Walter Otto's widow testified in Wüst's favor. She declared that her husband would never have taken a staunch National Socialist as a student. The Spruchkammer apparently believed the positive testimony and passed a mild judgment. Even more recent representations of Wüst's biography come to the conclusion that he never showed National Socialist zeal.

Wüst received his teaching license back on June 28, 1948. On the following September 1st he took up a position as a teacher at the Munich Wilhelmsgymnasium . From 1949 he again offered courses at the LMU, but without having been formally appointed as a private lecturer . His first course was the upper course “Exercises in the Greek History of the 4th Century. v. Chr. ”In the summer semester of 1949.

Alexander Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg was the new holder of the ancient history chair at LMU . In 1953 he applied for Wüst to be awarded the title of associate professor. This was rejected as premature, as was a second application the following year. The reason given by the university was that Wüst had not yet completed enough semesters in regular teaching. Another attempt by Stauffenberg in 1956, now flanked by Friedrich Klingner , met with resistance. Wüst was now being accused of having refused to become a private lecturer again for reasons of principle after his license to teach was reassigned. But Stauffenberg continued to stand up for Wüst and was able to influence the result in his favor by pointing out that the controversial matter was an oversight by the faculty.

On April 10, 1957, there was a formally valid appointment as a private lecturer, and on October 15, 1958, the dean's office applied for Wüst to be appointed associate professor. This also happened on December 12, 1958. Wüst did not receive any payments for his academic teaching activities, however, he earned the income for his family solely from his ongoing work as a high school teacher.

For three and a half years, Wüst had to bear the double burden of university work and school service. After there was still no indication of an appointment to a full professorship, he returned his teaching license (Venia legendi) on July 31, 1962 . On September 1st of that year he was transferred to the Chiemgau-Gymnasium in Traunstein and was only active as a teacher afterwards. On February 1, 1972, Wüst retired as director of studies.

Fritz Rudolf Wüst died on April 5, 1993 in Grassau. He was 80 years old. The largely forgotten scientist has never been given an obituary in any historical or ancient scholarly publication.

Research and Teaching

Greek history was the focus of research and teaching in Wüst. His lectures mainly dealt with the 4th century BC, Alexander the Great and Hellenism , but also the Persian Wars and Attic and Spartan history. Together with Stauffenberg he led an event entitled Political Journalism of the Greeks from 348–338 BC. Chr. To Roman antiquity taught Wüst little. He dedicated two seminars to the letters of Pliny Minor and a lecture on Roman history since the Gracchi . Wüst's most important study was his dissertation on Philip II . Furthermore, with a few essays, he influenced the 4th century BC in particular. The research. His habilitation remained unpublished.

Wüst's lectures were objective and matter-of-fact and above all aimed at training future high school teachers. Here his ability to bring science and high school together was shown. One of his most important concerns was to show the students the requirements of their future careers. At a time when this function was only just beginning to emerge, Wüst gained considerable importance as a student advisor for young academics at the LMU. In his practice-oriented didactics, he benefited not least from his parallel teaching activities, which made him aware of the usefulness of supporting measures for students as well. Karl Christ sums up that Wüst's contribution to the ancient history seminar of the LMU as an institution was of inestimable importance after the war.

The researcher Wüst is not to blame for the narrow oeuvre alone. A number of unfavorable circumstances hampered Wüst's academic career not only in the post-war period, when the negative consequences of his early adaptation to National Socialism came to the fore. As early as the 1930s, the need to provide for one's own living resulted in repeated compromises at the expense of his ambitions as a researcher. In addition, he was not one of the students of Berve and Weber, the most influential ancient historians of the Nazi era. With the loss of his doctoral supervisor Otto, he not only lacked a leading academic figure, but also a mentor. This proved to be a particular disadvantage in the German university landscape, which is heavily geared towards personal ties and where positions were often given to the protégés of professors. The Second World War meant that Wüst could initially only hold a few basic Latin courses and style exercises. Until the end of the war he did not have the opportunity to implement his Venia legendi. In addition, Wüst was affected by internal university quarrels several times, for example in the course of his habilitation or in the attempts to become an associate professor. In addition, from 1949 he increasingly concentrated on teaching. The return of the teaching license, probably out of resignation, marked the premature end of a career as a researcher that had once started promisingly.

After receiving little recognition for a long time, Wüst has again attracted more attention since the beginning of the third millennium. For an anthology for the centenary of ancient history at LMU in 2001, the ancient historian Tanja Scheer wrote an article in which Wüst's biography was presented in more detail for the first time. To do this, Scheer evaluated the historian's academic legacy, inspected his personal file and looked at the LMU's lecture directories from 1938 to 1962. In addition, in 2008 Karl Christ Wüst dedicated several pages of his biography to Alexander von Stauffenberg.

Fonts

- University publications

- Philip II of Macedonia and Greece in the years from 346 to 338 (= Munich historical treatises . Issue 14). CH Beck, Munich 1938 (extended dissertation).

- Koine Eirene. The development of political expressions of Panhellenism in the period from the sixth century to the beginning of Hellenism . LMU, Munich 1942 (unprinted habilitation thesis).

- Essays

- On the problem of “imperialism” and “power political thinking” in the age of the polis . In: Klio . Volume 32, 1939, ISSN 0075-6334 , pp. 67-88.

- The march of Leotychidas against Thessaly in 477 BC. Chr. In: Symbolae Osloenses . Volume 30, 1953, ISSN 0039-7679 , pp. 61-67.

- The speech of Alexander the great in Opis. Arrian VII 9-10 . In: Historia . Volume 2, 1953/1954, ISSN 0018-2311 , pp. 177-188.

- The mutiny of Opis . In: Historia . Volume 2, 1953/1954, ISSN 0018-2311 , pp. 418-431.

- Amphictyony, Confederation, Symmachy . In: Historia . Volume 3, 1954/1955, ISSN 0018-2311 , pp. 129-153.

- To the prytánies ton naukráron and to the old Attic Trittyen . In: Historia . Volume 6, 1957, ISSN 0018-2311 , pp. 176-191.

- Thoughts on the Attic Estates. An attempt . In: Historia . Volume 8, 1959, ISSN 0018-2311 , pp. 1-11.

- On the hypomnemata of Alexander the great. The tomb of Hephaestion . In: Annual books of the Austrian Archaeological Institute in Vienna . Volume 44, 1959, ISSN 0078-3579 , pp. 147-157.

literature

- Karl Christ : The other Stauffenberg. The historian and poet Alexander von Stauffenberg . CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56960-9 , pp. 66-69.

- Tanja Scheer : Fritz Rudolf Wüst . In: Jakob Seibert (Ed.): 100 Years of Old History at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich (1901-2001) (= Ludovico Maximilianea. Research . Volume 19). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-428-10875-2 , pp. 128-136.

Web links

- Literature by and about Fritz Rudolf Wüst in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, this article is based on Tanja Scheer: Fritz Rudolf Wüst . In: Jakob Seibert (Ed.): 100 Years of Old History at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich (1901-2001) . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2002, pp. 128-136.

- ↑ Otto's letter to the Dean's Office of the Philosophical Faculty (I) dated November 12, 1936: UAM, PA-allg.-1075.

- ↑ Characterization of the Wüst – Otto relationship based on: Karl Christ: Der Andere Stauffenberg. The historian and poet Alexander von Stauffenberg . CH Beck, Munich 2008, p. 67.

- ↑ Christ: The Other Stauffenberg , p. 68.

- ↑ So Christ: Der Andere Stauffenberg , p. 68.

- ^ Annex to the “Small Questionnaire” on denazification of February 1, 1946 (UAM, E-II-3636).

- ↑ On Wüst as an academic teacher, see Christ: Der Andere Stauffenberg , pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Christ: The Other Stauffenberg , p. 69.

- ^ So the pointed evaluation of Scheer, p. 135.

- ↑ File inventory: UAM, PA-allg-1075; E-II-3636 (Wüst personnel file); ON-14 (Fritz Wüst)

- ↑ Here Christ referred largely to Scheer's preliminary work; in addition, he contributed his own assessments and experiences.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wüst, Fritz Rudolf |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wüst, Fritz Rudolph; Wüst, Fritz |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German ancient historian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 19, 1912 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Glatz , Province of Silesia |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 5, 1993 |

| Place of death | Grassau |