Gaudo culture

The Gaudo culture was an Eeolithic , archaeological culture in southern Italy with the main distribution period between 3150 and 2950 BC. Chr. It is mainly about their necropolis defined.

Type locality

The Gaudo culture, Italian cultura del Gaudo , is named after its eponymous type locality , the necropolis Spina-Gaudo . The site is located near the mouth of the Sele in Campania ( Salerno province ), only one kilometer from the famous temple complex of Paestum . It consists of a necropolis of 2000 square meters, which is composed of a total of 34 tombs. The facility was discovered towards the end of 1943 when the Allies expanded the Gaudo airfield as part of Operation Avalanche . Initial investigations were recorded by the British Air Force officer and archaeologist Lieutenant John GS Brinson. In the years that followed, several excavation campaigns were carried out, particularly under the direction of PC Sestieri, and research continued into the 1960s.

necropolis

Each individual grave unit, which consists of one or two oval grave chambers with a flat vaulted ceiling, was cut out of the rock in the shape of an oven. Each of the chambers contained several human skeletons interred in the fetal position, either on the side or on the supine position. Access was from above via a more or less circular shaft that ended in a vestibule-like antechamber. There is evidence that the funeral ceremonies were performed by a larger group who then closed the entrance with a large stone at the end. Obviously, the burial chambers were also reused several times - recognizable by the fact that the last person to be buried was always laid down at the end of the chamber, surrounded by his predecessors.

Fine ceramic objects such as Askoi , weapons such as arrow and lance tips, but also knives made of flint and copper served as grave goods .

Cultural influences

The Gaudo culture shows numerous foreign cultural influences, especially from the eastern Mediterranean such as the Aegean region or the coastal area of Anatolia . The similarities in the characteristics of the ceramics and the metal weapons tempted some researchers to look for the origin of the Gaudo culture even in the Aegean Sea or in Anatolia itself. However, such hypotheses are no longer supported. In Italy, the interrelationships between the Gaudo culture and its contemporaneous subsidiary cultures can be observed at several sites, especially at the sites in the peripheral area. For example, at the Tenuta della Selcetta 2 site south of Rome, in the same tomb, ceramics from the Rinaldone culture and those from the Gaudo culture were found. Other sites in Lazio also show the simultaneous occurrence of various cultural influences. For example, in Maccarese - Le Cerquete Fianello ceramics of the Canelle type were associated with Rinaldone and Gaudo ceramics. The influence of Gaudo culture can still be felt in Tuscany . In the Sassi Neri cave near Capalbio , ceramics were discovered which are very similar in shape to the Campanian vessels. In some tombs in Tuscany, southern stylistic elements of the Gaudo and Laterza cultures can be felt, recognizable by the bottle-shaped vases, the biconical vases, the keel bowls and others. Some types of vases, on the other hand, resemble comparable objects from the Sardinian Abealzu culture . Conversely, a vase of the Sardinian Monte Claro culture appeared on the peninsula under Gaudo material. Finally, the relationship between the ceramics of the Gaudo culture and those of the contemporary cultures of Sicily should be emphasized.

Way of life

Several factors support the assumption that the people of the Gaudo culture lived as nomads . This is also indicated by the extremely low number of known settlements. The people probably lived in makeshift structures that left no archaeological traces. Compared to structures made of stone, such shelters are ideal for a very mobile way of life.

There are also many indications of a predominance of animal husbandry . Examination of the tooth enamel of the deceased suggests a carnal diet . This is also underlined in the tombs by the bone finds of domestic animals such as cattle.

Dogs were buried next to the deceased several times. In a nomadic population, guard dogs have a high priority for the cohesion of the herd (s).

The high number of sites at altitudes that are not favorable for arable farming is also striking, but which were well suited for transhumance. However, sites in the fertile plains are well known.

Overall, a large part of the population of Gaudo culture consisted of nomadic shepherds , but the social reality of that time may have been a bit more nuanced. Interestingly, in the necropolis of Pontecagnano, in addition to the bones of sheep, goats, cattle and dogs, pig bones were also found. Pigs, on the other hand, are difficult to integrate into a nomadic lifestyle.

Finally, villages are known which suggest a permanent sedentary way of life. In Selva dei Muli in Latium, for example, mills and found grinding stones indicate grain processing . There are also clear indications for fishing in Selva dei Muli based on net weights found. The hunt is in turn occupied by wild boar tusks, which act as grave goods in some tombs.

The people of the Gaudo culture did not only buy food but also did handicrafts such as B. ceramic production or the production of tools and weapons from flint or metal .

Settlements

In the main distribution area of Gaudo culture in Campania, very few settlements are known. Rare exceptions like Fratte at Salerno are poorly documented. The settlements are somewhat more common on the edge of the distribution area in Lazio. They are usually located in areas suitable for arable farming, such as B. the site of Le Coste on Lake Fucin in Abruzzo. Natural caves have also been found in the Naples area .

Selva dei Muli near Frosinone in southern Lazio has brought important new information to light. The settlement was girded by a palisade , the defensive task of which leaves no doubt. A rectangular hut 10 meters long was also excavated. Since only post holes could be identified, it had evidently been built of a perishable material, probably wood. Other post holes found enabled the reconstruction of outbuildings in which the cattle were housed. Ceramic remains provide further indirect information about the huts. So pot lids made of terracotta were discovered in various graves, which are to be regarded as replicas of the huts in terms of morphology and decor. The latter were therefore of a cylindrical nature with a roof shape in the form of a somewhat compressed cone.

A global analysis of all sites including the necropolises shows that the majority of the sites were located on natural traffic routes such as valleys that connected the individual regions. This also includes the Toppo Dagguzzo site , which may already be part of the Taurasi culture. Toppo Dagguzzo was fortified on a strategic hill and controlled the side valleys flowing into it from Campania, Apulia and Basilicata .

With the exception of the Spina-Gaudo type locality, the coastal zone had no special priority. However, recent discoveries indicate that some of the foreign trade was carried out by sea. The trade in copper , which was shipped as metal bars or in ore form, is of great interest here .

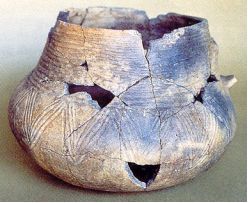

Ceramics

Ceramics are quite common in the grave complex . Their execution is usually quite neat, but occasionally firing errors can be noticed, which are characterized by alternating reddish and dark spots. The vases have a broad spectrum of forms such as Askoi , urns , long-necked bottles, amphorae , pots, pyxides , glass jars, cups, glasses, plates, bowls and doppelhalsige salt shaker. Miniature forms are also known. The pottery is usually poorly decorated, with the exception of a few vases, which have been decorated with zigzag incisions and stamps forming geometric patterns. With the exception of the terracotta house models mentioned above, there are no figurative representations. Decorations made of clay applied like scales are very rare.

Stone artifacts

Stone artifacts were mainly found in tombs, but they are rare in settlements. Despite intensive excavations, only 40 stone artefacts were discovered in the Selva dei Muli settlement , mostly flint bulbs worked using the cutting technique and 3 or 4 arrowheads. The Le Coste site in Abruzzo, on the other hand, had its own workshop for flint arrowheads .

In addition to the local rocks, the people of the Gaudo culture also imported other types of rock such as the rare obsidian . In Selva dei Muli, three obsidian artefacts were discovered which came from Palmarola and Lipari . An obsidian arrowhead came to light in the Tor Pagnota tomb near Rome .

The stone artifacts in the tombs consist mainly of the Gargano flint . It is possible that the flint was mined there by the people of Gaudo culture themselves, as burials that are assigned to Gaudo culture were found in the former mine of Valle Sbernia / Valle Guariglia near Peschici . However, this assignment is not generally recognized, as it could also be graves of the Laterza culture.

The flint of the Gargano was used to make large blades , which were produced using printing technology and were up to 21 centimeters long and 4.1 centimeters wide. Their average thickness was 11 millimeters. More than 200 blades are known so far. Most were systematically retouched into daggers, but many were also used as knives. Worn blade edges have been redesigned.

Two-sided daggers ( French: bifaces ) were also mainly made from Gargano flint and only rarely from other materials. Several tens of finds exist from them. They emerged from large flakes of large flint bulbs and are 10 to 30 centimeters long. The retouching was done very neatly and covers the entire surface. The two-sided daggers were sometimes used as knives.

The mostly very neatly crafted arrowheads are far more numerous than daggers. They too are mainly made of Gargano flint. Its enormous size (more than 10 centimeters!), However, makes it doubtful that it can be used for hunting purposes, but rather suggests a ritual purpose.

Tips were also made from other materials, but it cannot be decided whether they served as a projectile or were mounted on a handle as a cutting tool.

Tools made from bone and antlers

Tools made of bones and antlers are only of secondary importance, but at least in the village of Selva dei Muli they had a certain importance. They are almost completely absent from the necropolises, with the exception of Pontecagnano, where the remains of a metal dagger were found, the handle of which was encased in bone material.

Polished stone tools

Polished stone tools are also rarely found in Gaudo culture. There are only a few finds, all of them small in size. Two fragments of polished stone axes emerged in Selva dei Muli.

Metal processing

Metal finds were made exclusively in the necropolis. Overall, they are rare. Of the 2000 found objects reviewed, only 1.5% are made of metal. Some necropolises, such as Eboli, have no metal finds at all.

Daggers of various shapes are predominant. They are usually very elongated, but often too thin-walled for them to be used as weapons. Maybe they were used as knives.

Also striking are halberds with large triangular blades that were attached perpendicular to the handle. Only one very small ax is known to originate from the Madonna delle Grazie necropolis in Mirabella Eclano .

The daggers are made of arsenic-rich copper. Two bangles are made of silver . The daggers in particular are characteristic of Gaudo culture in terms of their shape and were probably made by hand in their own workshops. However, it should be noted that there are no copper deposits in Campania and the metal therefore had to be imported.

Trinkets

Jewelry items are rare. In addition to the two silver bracelets, which were already mentioned above, there were needles made of bone with T-shaped heads and wild boar tusks. In the Madonne delle Grazie necropolis in Mirabello Eclano, a rod made of sandstone was found, the pommel of which was rounded.

Woven goods

Loom weights and spindles were found in several graves and traces of weaving can also be found in the village of Selva dei Muli . The woven goods produced, however, have not survived and are completely unknown.

Graves and funeral rites

In addition to burials in natural caves and in trenches, the tombs, as already mentioned, were mainly laid out in small dome graves that were carved out of the standing area and accessible via a vertical shaft. In Bucino in Campania, two types of tombs can be identified - large, deep-lying domed tombs as well as smaller, near-surface tombs, whereby the individual tombs can be combined to form a more or less stately necropolis. The type locality Spina-Gaudo is certainly the most important of the various necropolises with an area of around 2000 square meters. Various excavation campaigns have so far identified 45 different types of tombs, and there were probably more, as many structures were destroyed without leaving any traces.

The funeral rites during the Gaudo culture are likely to have been very different and complex, but they still show certain regularities. It seems that not all members of the society of that time were buried in the tombs. Newborns are not among those buried and a selection also took place among the adults. In Pontecagnano , for example, there are no small children.

The number of those buried in the burial chambers is also subject to fluctuations and a completely empty crypt itself was found. Nevertheless, most of the burial chambers were occupied several times, with the predecessors being pushed back. Some tombs also served as ossuaries . Usually the deceased were given ceramics and worked artefacts made of stone, sometimes daggers and arrowheads. Occasionally ocher was sprinkled on her head. The objects discovered at the entrance shafts, such as deliberately smashed vases, suggest grave rites. The remains of one and the same vase could be found in two different tombs.

In Palata 2 in Apulia, a small trench contained ceramic fragments that can be assigned to the Gaudo culture. The simultaneous presence of large bovine bones and small boulders, which had obviously been heated, suggests ritual practices .

Corporate structure

The presence of very rich grave goods in some necropolises could indicate a hierarchy in the middle of Gaudo culture. In the Madonna delle Grazie necropolis in Mirabella Eclano, for example, the tomb of Capo Tribù stands out clearly, as it can boast several daggers made of flint and metal, several tens on arrowheads, a scepter-like sandstone object and numerous ceramic remains. All of these items likely belonged to an individual who was buried with their dog.

Distribution area

The Gaudo culture developed mainly in the south of Campania . But it also spread to Latium , where it spread between 3130 and 2870 BC. Coexisted with the Rinaldone culture and the Ortucchio culture . More remote occurrences can be found in northern Calabria , in Apulia , in Abruzzo and on Ischia .

Sites

In Campania there are other Gaudo culture sites, such as B. the settlement in Taurasi and the necropolis of Eboli and Buccino .

The sites in detail:

- Spina-Gaudo near Paestum (type locality - necropolis)

- Buccino in Campania (necropolis)

- Caivano In Campania

- Santa Maria dei Bossi, near Casalbore in Campania

- Eboli in Campania (necropolis)

- Felci cave on Capri

- Fratte at Salerno

- Le Coste on Lake Fucin in Abruzzo

- Maccarese - Le Cerquete Fianello

- Madonna delle Grazie, at Mirabella Eclano in Campania (necropolis)

- Palata 2 in Apulia

- Piano di Sorrento in Campania

- Pontecagnano in Campania (necropolis)

- Roggiano Gravina in Calabria

- Selva dei Muli near Frosinone in Latium - village fortified with palisades

- Taurasi settlement

- Tenuta della Selcetta 2 near Rome

- Toppo Dagguzzo (possibly belonging to the Taurasi culture)

Museo archeologico nazionale di Paestum

In the National Archaeological Museum in Paestum , many artifacts of Gaudo's culture are on display.

chronology

The Gaudo culture was usually between 3000 and 2500 BC. Assigned - a rather imprecise statement that was not supported by any radiocarbon dating . Newer studies meanwhile allow a very precise chronological classification. According to this, the Gaudo culture developed from 3150 BC. And survived until 2300 BC. Its origins are undoubtedly to be found in the Taurasi culture , which was recently excreted in Campania and lasted from 3500 to 3250 BC. Existed. The Gaudo culture, for its part, was introduced as early as 2950 BC. Successively displaced by the Laterza culture , which was located in the southeast of the Italian peninsula.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Holloway, RR: Gaudo and the East . In: Journal of Field Archeology . tape 3 , 1976, p. 143-158 .

- ↑ a b Voza, G .: Considerazioni sul Neolitico e sull'Eneolitico in Campania . In: Atti della XVII Riunione Scientifica dell'Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria . Florence 1975, p. 51-84 .

- ↑ Salerno, A .: Inquadramento cronologico e culturale . In: Bailo, Modesti G., Salerno, A., Pontecagnano II, 5. La necropoli eneolitica, L'età del Rame in Campania nei villaggi dei morti (Eds.): Annali dell'Istituto Orientale di Napoli, sezione di Archeologia e Storia Antica, quad. N. 11 . Naples 1998, p. 143-156 .

- ↑ Anzidei, AP and Carboni, G .: Nuovi Contesti funerari eneolitici dal territorio di Roma . In: Martini, F. La cultura del morire nella società preistoriche e protostoriche italiane (ed.): Origines . Florence 2007, p. 177-186 .

- ^ A b Carboni, G .: Territorio aperto o di frontiera? Nuove prospettive di ricerca per lo studio della distribuzione spaziale delle facies del Gaudo e di Rinaldone nel Lazio centro-meridionale . In: Origini . tape XXIV , 2002, p. 235-301 .

- ↑ Carboni, G. and Salvadei, G .: Indagini archeologiche nella piana della Bonifica di Maccarese (Fiumicino - Roma), Il Neolitico e l'eneolitico . In: Origini . tape XVII , 1993, p. 255-279 .

- ↑ Grifoni Cremonesi, R .: Quelques observations à propos de l'Âge du cuivre en Italie central . In: De Méditerranée et d'ailleurs ... Mélanges offerts à Jean Guilaine, Archives d'Écologie Préhistorique . Toulouse 2009, p. 323-332 .

- ^ Contu, E .: La Sardegna preistorica e protostorica. Aspetti e problemi, Istituto italiano di preistoria e protostoria . In: Atti della XXIIe riunione scientifica nella Sardegna Centro-Settentrionale, 21-27 ottobre 1978 . Florence 1980, p. 13-43 .

- ↑ Melis, MG: La Sardaigne et ses relations méditerranéennes entre les Ve et IIIe millénaires av. JC, quelques observations . In: De Méditerranée et d'ailleurs ... Mélanges offerts à Jean Guilaine, Archives d'Écologie Préhistorique . Toulouse 2009, p. 509-520 .

- ^ Cocchi Neck , D .: Correlazioni tra l'Eneolitico siciliano e peninsulare . In: Origini . tape XXXI , 2009, p. 129-154 .

- ↑ a b Bailo Modesti, G. and Lo Porto, FG: L'Età del Rame nell'Italia Meridionale . In: Cocchi, D.Congresso Internazionale "L'Età del Rame in Europa", Viareggio 15-18 octobre 1987 (ed.): Rassegna di Archeologia . 7, Comune di Viareggio assessorato alla cultura, Museo Preistorico e Archeologico "Alberto Carlo Blanc", 1988, p. 315-329 .

- ↑ Fiori, O., Fornai, C. and Manzi, G .: Ai confini del Gaudo, una riconsiderazione dei resti scheletrici umani provenianti dai siti eneolitici di Cantalupo Mandela e Valvisciolo (Lazio Meridionale) . In: Origini . tape XXVI , 2004, p. 121-154 .

- ^ Bailo Modesti, G .: Le tombe e la morte nell'Età del Rame in Campania . In: Martini, F., La cultura del morire nella società preistoriche e protostoriche italiane (ed.): Origines . Florence 2007, p. 187-192 .

- ↑ Frezza, A .: Appendice B: Analisi faunistica . In: Bailo Modesti, G. and Salerno, A., Pontecagnano II, 5. La necropoli eneolitica, L'età del Rame in Campania nei villaggi dei morti (eds.): Annali dell'Istituto Orientale di Napoli, sezione di Archeologia e Storia Antica, quad. N. 11 . Naples 1998, p. 207-209 .

- ↑ Cerqua, M .: Selva dei Muli (Frosinone): un insediamento eneolitico della facies del Gaudo . In: Origini . tape XXXIII , 2011, p. 157-223 .

- ↑ a b Cipolloni Sampo, M., Calattini, M., Palma di Cesnola, A., Cassano, S., Radina, F., Bianco, S., Marino, DA, Gorgoglione, MA and Bailo Modesti, G., as well as the collaboration of Grifoni Cremonesi, R .: L'Italie du Sud . In: Guilaine, J. (Ed.): Atlas du Néolithique européen. L'Europe occidentale . ERAUL, Paris 1998, p. 9-112 .

- ↑ a b c Salerno, A .: Tipologia dei materiali . In: Bailo Modesti, G. and Salerno, A., Pontecagnano II, 5. La necropoli eneolitica, L'età del Rame in Campania nei villaggi dei morti (eds.): Annali dell'Istituto Orientale di Napoli, sezione di Archeologia e Storia Antica, quad. N. 11 . Naples 1998, p. 93-142 .

- ^ Giardino, C .: The beginning of metallurgy in Tyrrhenian south-central Italy . In: Ridgway, D., Serra Ridgway, F., Pearce, M., Herring, E., Whitehouse, RD and Wilkins J. (Eds.): Ancien Italy in its Mediterranean Setting: Studies in Honor of Ellen Macnamara, Accordia Specialist Studies on the Mediterranean . volume 4, Accordia Research Institute, University of London, 2000, p. 49-65 .

- ↑ Gangemi, R .: L'industria litica del sito eneolitico di Selva dei Muli (Frosinone) . In: Origini . tape XXXIII , 2011, p. 225-232 .

- ↑ Acquafredda, P., Mitolo, D. and Muntoni, IM: Provenienza delle ossidiane di Selva dei Muli (Frosinone) . In: Origini . tape XXXIII , 2011, p. 233-236 .

- ↑ a b Guilbeau, D .: Les grandes lames et les lames par pression au levier du Néolithique et de l'Énéolithique en Italie . In: Doctoral thesis, Université Paris-Ouest . Nanterre 2010.

- ↑ Tunzi, AM: Valle Sbernia / Guariglia . In: Tarantini, M. and Galimberti, A., Le miniere di selce del Gargano, VI – III millennio aC Alle origini della storia mineraria europea (ed.): Rassegna di Archeologia - Preistoria e Protostoria 24A, All'Insegna del'Giglio . Borgo S. Lorenzo 2011, p. 238-243 .

- ↑ Negroni Catacchio, N. and Miari, M .: Problemi di cronologia della facies di Rinaldone . In: Negroni Catacchio, N., Paesaggi d'Acque, Preistoria e Protostoria in Etruria (ed.): Atti del Quinto Incontro di Studi, Centro Studi di Preistoria e Archeologia . tape 2 . Milan 2002, p. 487-508 .

- ^ Giardino, C .: Appendice C: nuovi dati sulla metallurgia della facies del Gaudo. I pugnali da Pontecagnano e da Paestum . In: Bailo Modesti, G. and Salerno, A., Pontecagnano II, 5. La necropoli eneolitica, L'età del Rame in Campania nei villaggi dei morti (eds.): Annali dell'Istituto Orientale di Napoli, sezione di Archeologia e Storia Antica, quad. N. 11 . Naples 1998, p. 210-215 .

- ^ Holloway, RR: Excavations at Buccino 1969 . In: American Journal of Archeology . 1970, p. 145-148 .

- ^ Bailo Modesti, G. and Salerno, A .: Il Gaudo d'Eboli . In: Origini . tape XIX , 1995, p. 327-393 .

- ↑ Laforgia, E., Boenzi, G. and Signorelli, C .: Caivano (Napoli). Nuovi dati sull'Eneolitico dagli scavi AV La necropoli del Gaudo . In: Amilcare Bietti, Strategy di insediamento fra Lazio e Campania in età preistorica e protostorica (ed.): Atti della XL Riunione Scientifica, Roma, Napoli, Pompei, November 30th - December 3rd 2005, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria . tape 2 . Florence 2007, p. 615-618 .

- ↑ Radina, F., Sivilli, S., Alhaique, F., Fiorentino, G. and D'Oronzo, C .: L'insediamento neolitico nella media valle ofantina: l'area di Palata (Canosa di Puglia) . In: Origini . tape XXXIII , 2011, p. 107-156 .

- ^ Barker, G .: Landscape and Society, prehistoric central Italy . Academic Press, London, New-York, Toronto, Sydney, San-Francisco 1981.

- ↑ Holloway, RR: Buccino, The Eneolithic necropolis of S. Antonio and other prehistoric discoveries made in 1968 and 1969 by Brown University . De Luca Editore, Rome 1973.

- ↑ Laforgia, E. and Boenzi, G .: La necropoli eneolitica di Caivano (Napoli) . In: Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche . tape LIX , 2009, p. 181-218 .

- ↑ Albore Livadie, C. and Gangemi, G .: Sepolture eneolitiche da Casalbore, loc. S. Maria dei Bossi (Avellino) . In: Cocchi, D. Congresso Internazionale "L'Età del Rame in Europe", Viareggio 15-18 octobre 1987 (ed.): Rassegna di Archeologia . 7 Comune di Viareggio assessorato alla cultura, Museo Preistorico e Archeologico "Alberto Carlo Blanc", 1988, p. 572-573 .

- ↑ Passariello, I., Talamo, P., D'Onofrio, A., Barta, P., Lubritto, C. and Terrasi F .: Contribution of Radiocarbon Dating to the Chronology of Eneolithic in Campania (Italy) . In: Geochronometria . tape 35 , 2010, p. 5-33 .

- ↑ Talamo, P .: Le aree internal della Campana centro-settentrionale durante le fasi evolute dell'Eneolitico: osservazioni sulle dinamiche culturali . In: Origini . tape XXX , 2008, p. 187-220 .