Hermann Zapf

Hermann Zapf (born November 8, 1918 in Nuremberg ; † June 4, 2015 in Darmstadt ) was a German typographer - primarily a font designer -, calligrapher , author and teacher. Since 1951 he was married to Gudrun Zapf-von Hesse .

Live and act

Hermann Zapf attended the grammar school in Nuremberg. His childhood wish to become an electrical engineer was prevented by the Nazi regime in Germany for the son of an active trade unionist , as the father became unemployed on May 2, 1933 when the free trade unions were banned. In 1934 he therefore began an apprenticeship as a positive retoucher . During his apprenticeship he came into contact with the life and work of the German writer Rudolf Koch through an exhibition and the book Writing as Artistic Craft . This stimulated his interest so much that he began to deal with the requirements and topics of artistic font development on an autodidactic basis. After completing his apprenticeship as a retoucher in 1938, where he deepened his passion for calligraphy even further, Zapf moved to Frankfurt am Main, where he worked as a type graphic artist and calligrapher. In the same year he also designed his first type, Gilgengart , for his future employer, the type foundry D. Stempel AG .

He began his professional career in the writing and sheet music studio “Haus zum Fürsteneck” with Paul Koch (* 1906). During this time he was already doing individual jobs as a typeface and book designer. Working with D. Stempel AG, he also learned the art of punch cutting. In 1939 he began working on his calligraphy book, pen and graver .

On April 1, 1939, he was drafted into the Reich Labor Service to strengthen the Siegfried Line against France . Not used to the hard work, he soon developed heart problems and was transferred to the back office to write camp logs in Kurrent script . During the Second World War, at the beginning of September 1939, his entire working group was drafted into the Wehrmacht , but only Zapf was rejected because of his heart problems. In 1941 he was drafted into the Wehrmacht. Because of his health problems, he was assigned to a cartographic unit and sent to Bordeaux as a map-maker to draw secret maps of Spain, especially of the rail network. Towards the end of the war he was taken prisoner by France, but was treated well there and, due to his poor health, was released four weeks after the end of the war to his home in Nuremberg.

In Nuremberg he was initially working as a freelancer in his field. Since D. Stempel AG had offered him a position, Zapf returned to Frankfurt am Main in 1947, where he was artistic director from 1947 to 1956. Between 1948 and 1950 he was also active as a part-time lecturer for typography at what was then the Werkkunstschule, today's Hochschule für Gestaltung (HfG) in Offenbach am Main . During this time, from 1951 to 1954, Zapf also designed twelve postage stamps for the Deutsche Bundespost .

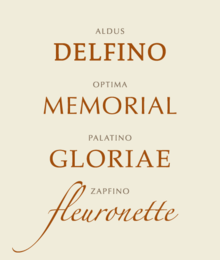

In addition, Hermann Zapf worked as a graphic artist in book design for various publishing houses such as Suhrkamp , Insel (also Insel-Bücherei ), the Gutenberg Book Guild or the Carl Hanser Verlag . As a matter of principle, however, he never worked for advertising agencies. Another important activity was that of the type designer; the Palatino , Aldus and Optima were created (as early as 1952), which quickly established themselves and are still widely used today. Since the "Optima" offered a very clear and at the same time filigree typeface, it was particularly popular with the advertising industry. As with some others, the Optima was illegally copied by US product robbers and a. used for the lettering of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington.

For the first time, Zapf participated with his work in 1951, together with Fritz Kredel (1900–1973), in an exhibition at the Cooper Union Museum in New York . He organized his first solo exhibition in 1952 at the Grafiska Institute Stockholm. In 1951 he married Gudrun von Hesse, who also worked as a typographer and bookbinder. Their son Christian Ludwig (deceased 2012) emerged from the marriage. He also expanded his previous teaching activities in the international field. In 1954, for example, he lectured at Yale University in the United States in his field. In the same year his book Manuale Typographicum was published , a new edition of which was then translated into 18 languages in 1968.

From 1956 he worked again as a freelance type graphic artist and calligrapher in Frankfurt. In 1957 he also held his lecture program at the US University of California in Los Angeles and in 1960 was professor of graphic design at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. In Germany, he carried out orders for the Insel-Verlag, the Gutenberg Book Guild, the Hanser and Suhrkamp Verlag, among others. For the latter, he designed the publisher's signature. For example, one of his international work as a calligrapher in 1960 was the preparation of the preamble to the Charter of the United Nations in four languages for the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. In the same year his book About Alphabets was published in German and English.

Since the early 1960s, Hermann Zapf has dealt with the combination of typography and computer programs and has been a member of the International Center for the Typographic Arts (ICTA) since then . In Germany, his ideas on computer-aided typesetting were not yet taken seriously and even laughed at. At Harvard University , USA , in 1964 he gave lectures on the development of typographic computer programs. He lectured on the same topic at Princeton University . After a lecture in the USA in the same year, the University of Texas in Austin was very interested in Zapf and wanted to set up a professorship for him. He declined the offer because his wife did not want to live in the United States forever.

In 1969 he developed the Hallmark Textura font and the Pannigerian alphabet . In the mid-1960s he received several awards for his international achievements in the field of type development, for example he received the 1st prize for typography at the Brno Biennale in 1966 and the first gold medal from the Type Directors Club of New York a year later . In 1969 he was awarded the Frederic W. Goud Award for Typography in Rochester.

In 1971, Herman Zapf began working with the US computer scientist Donald E. Knuth (* 1938). The cooperation took place in such a way that Zapf developed the appropriate fonts and Knuth the necessary IT-based typesetting programs. Zapf worked on the development of the fonts for the TeX typesetting program developed by Knuth . For example, this led to the development of the Euler family of fonts for the American Mathematical Society .

In 1972 he was given a teaching position for typography at the Technical University of Darmstadt , which he held until 1981. In 1976, the Rochester Institute of Technology was the first university to offer him the professorship for computer-aided typography, which was established there as a department for the first time worldwide. He accepted this offer and, alternating between Darmstadt and Rochester, taught from 1977 to 1987 at the College of Graphic Arts and Photography . In doing so, he mainly dealt with the requirements of harmonizing the artistic ideas of typography with the technical conditions of computer use. Together with Knuth, Zapf published a documentation on the Euler font family in 1989. In addition to the Latin letters, it includes a Greek, a Fraktur and a cursive script. This documentation was published under the title AMS-Euler. A New Typeface for Mathematics .

In 1977 he founded, together with Aaron Burns († 1991) and Herb Lubalin the company Design Processing International Inc. in New York. The aim was to develop programs for typographical structures that could also be used by non-specialists. The company existed until 1986. After Herb Lubalin's death, Zapf, Burns & Company was founded in 1987 . Burns also died in 1991, and two employees stole the company's ideas to start their own business. Since it was impractical to run a New York company from Darmstadt, Zapf closed this company too. In the meantime the German market had opened up for these topics. From 1986 onwards, Zapf developed the “ hz program ” computer program in cooperation with URW Software & Type GmbH in Hamburg . This contains micro-typographical changes for better line adjustment. The European patent, registered in 1984, was acquired by the US software company Adobe, which implanted this method in the layout and software program InDesign .

In his later years, Hermann Zapf expanded his Palatino script in particular to include Greek and Cyrillic characters. He also worked on the Zapfino typeface series , which began in 1993 and which was eventually published by Linotype . Another highlight of his artistic activity was that in 2001 the Apple company acquired the Zapfino font he had developed and had it digitized by the Japanese graphic designer Akira Kobayashi (born 1960).

In total, Zapf designed over 200 typefaces in his professional life, which made him known more and more at home and abroad as an innovative and talented German draftsman. Hermann Zapf died on June 4, 2015 in Darmstadt at the age of 96. Hermann Zapf was buried in the old cemetery in Darmstadt (grave number: II P 44).

An important collection of typeface drafts, book designs and signets by Hermann Zapf is located in the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel and can partially be viewed in a permanent exhibition.

Fonts

Hermann Zapf designed over 200 typefaces. The best known of these are: Palatino, Aldus, Optima, Zapfino, Zapf Book, Zapf Dingbats and Zapf Chancery . He also designed some broken fonts such as the Gilgengart (1938) and the Hallmark Textura (1969) as well as the Pannigerian alphabet . Here is a list of his fonts listed in the Linotype Library:

- Aldus (1954)

- Aldus nova (2005) together with Akira Kobayashi

- AMS Euler (1981)

- Aurelia (1983)

- Edison (1978)

- Compact (1954)

- Marconi (1976)

- Medici Script (1971)

- Melior (1952)

- Noris Script (1976)

- Optima (1958)

- Optima nova (2002) together with Akira Kobayashi

- Orion (1974)

- Palatino (1950)

- Palatino Arabic (2005) together with Nadine Chahine

- Palatino nova (2005) together with Akira Kobayashi

- Palatino Sans (2007) with Akira Kobayashi

- Palatino Sans Arabic (2010) together with Nadine Chahine

- Sapphire (1953)

- Sistina (1950)

- Vario (1982)

- Virtuosa Classic (2009) together with Akira Kobayashi

- Venture (1969)

- Linotype Zapf Essentials (2002)

- Zapfino (1998)

- Zapfino Extra (2003)

- Together with Akira Kobayashi, Hermann Zapf revised the Zapfino font in 2003 and published it as Zapfino Extra .

- ITC Zapf Chancery (1979)

- ITC Zapf International (1976)

- ITC Zapf Book (1976)

- Zapf Renaissance Antiqua (1984–1987)

- ITC Zapf Dingbats (1978)

honors and awards

- 1967: Type Directors Club Medal of the Type Directors Club

- 1974: Gutenberg Prize of the Gutenberg Society

- 2000: Honorary member of the German-speaking user association TeX

- 2003: SoTA Typography Award from the Society of Typographic Aficionados in Chicago

- 2003: Corresponding member of the Grolier Club .

- 2007: Goethe plaque from the state of Hesse

- 2010: Cross of Merit 1st Class ("Federal Cross of Merit ")

- 2016: posthumously (with his wife Gudrun Zapf-von Hesse) art prize of the Ike and Berthold Roland Foundation.

Publications (selection)

- Alphabet stories. A chronicle of technical developments. Mergenthaler Edition / Linotype, Bad Homburg 2007, ISBN 3-9810319-5-4

literature

- Rick Cusick: What our lettering needs: The contribution of Hermann Zapf to calligraphy & type design at Hallmark Cards. RIT Cary Graphic Arts Press, Rochester, NY 2011, ISBN 978-1-933360-55-3 .

- Nikolaus Weichselbaumer: The typographer Hermann Zapf. A work biography. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2015, ISBN 978-3-11-041498-1 .

- Two lives for the art of writing: a film documentary shows the work and successes of Hermann Zapf and Gudrun Zapf-von Hesse. FAZ of November 10, 2018.

Web links

- Literature by and about Hermann Zapf in the catalog of the German National Library

- Zapf's autobiography at Linotype ( PDF , English; 207 kB)

- The art of Hermann Zapf , short film (in English) on YouTube

- Zapf, Hermann. Hessian biography. (As of June 4, 2020). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

Works :

Article :

- Detlef Borchers: The typist of the computer age: Hermann Zapf for the 90th In: heise online. November 8, 2011, accessed May 10, 2015 .

- The ABC of Hermann Zapf. Portrait - One of the world's most important typographers celebrates his 95th birthday on Friday in Darmstadt. In: Echo Online - News from South Hesse. November 7, 2013, accessed June 10, 2015 .

- Jürgen Siebert: Hermann Zapf 1918–2015. In: FontBlog. Monotype GmbH ( Linotype ), June 6, 2015, accessed on June 10, 2015 (biography with further typeface examples and a list of 21 [as of June 16] further online obituaries).

Individual evidence

- ^ Hermann Zapf: Obituary notice. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . June 10, 2015, accessed June 16, 2015 .

- ↑ Ulf Erdmann Ziegler: To the death of the writing connoisseur Hermann Zapf. Culture today. In: Deutschlandfunk . June 6, 2015, accessed June 6, 2015 .

- ↑ Hermann Zapf, 96, Dies; Designer Whose Letters Are Found Everywhere. In: The New York Times . June 10, 2015, accessed on June 13, 2015 (English, see June 10 correction below).

- ^ Entry by Zapf Hermann in Munzinger Online / Personen-Internationales Biographisches Archiv, in: https://www.munzinger.de/search/document

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Zapf, Hermann |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German typographer, calligrapher, author and lecturer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 8, 1918 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Nuremberg |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th June 2015 |

| Place of death | Darmstadt |