Alpirsbach Monastery

The monastery Alpirsbach is a former Benedictine abbey in Alpirsbach , in the style of Romanesque was built. The cloister is in the Gothic style . The monastery was founded on January 16, 1095 by Bishop Gebhard III of Constance . consecrated.

history

founding

Closely connected to the Gregorian church reform, monks from St. Blasien first settled in the Black Forest town in 1095 . The nucleus of the monastery was a former Predium , an estate that was probably created during the clearing colonization of the High Middle Ages. The estate stretched from Ehlenbogen in the north to Schenkenzell in the south, from Wolfbachtal in the east to Heimbachtal in the west. Donors were the Counts Alwik von Sulz , Adalbert von Zollern and the noble free Ruodman von Hausen from Neckarhausen, the consecration took place by the Constance Bishop Gebhard on January 16, 1095. The Constance Bishop and the St. Blasier Abbot Uto I granted the monastery Free election of abbots and bailiffs as well as unlimited ownership and administrative rights. The first abbot of the new monastery was Kuno, who came from St. Blasien. The Bishop of Constance inaugurated the first stone oratorio as early as 1099. In 1101 the monastery complex was placed under papal protection by Pope Paschal II , and Emperor Heinrich V confirmed these rights in 1123. In 1128 the large monastery church was consecrated by Bishop Ulrich II of Constance. In the early days of the new monastery, the influence of the Hirsau monastery grew , so that the second and third abbots came from this monastery.

Development of the monastery

In the following years most of the abbots came from the lower nobility of the monastery area. The fortune was divided into individual liens, the aristocratic way of life and mentality gained more and more the upper hand in the monastery. The monastery reached a certain boom in the 14th century under the abbots Walter von Schenkenberg (1303–1336) and Brun von Schenkenberg (1337–1377), who were buried in the monastery and whose epitaphs have been preserved on site to this day. There were some new buildings, but the monastery's income remained declining.

In 1293 a rector puerorum and thus a monastery school was mentioned, in 1341 the Franciscan convent in Kniebis Alpirsbach became a priory .

Hereditary bailiwick rights, originally with the Lords of Zollern , finally came to the Counts of Württemberg via the Dukes of Teck and the Dukes of Urslingen . They pushed for the monastery to regain its strength and for the monks to live according to the rules.

The 15th century saw the monastic community in a dispute between the Benedictine reform movements and the reform opponents, which finally led to the fact that the convent was dissolved by 1455 under Abbot Conrad Schenk von Schenkenberg (monk from 1414-1446, abbot 1451). Approx. 20 years later Georg Schwarz became abbot of the monastery. Under him and under the influence of monks from Wiblingen who belonged to the Melker Observanz, the Alpirsbach Abbey joined the Melk Reform in 1471 , albeit against the resistance of the long-established monks.

Abbot Hieronymus Hulzing (1479–1495) led the Benedictine Abbey to the Bursfeld Congregation - as it were as the second founder ( secundus fundator ) (1482). The reform efforts led to a new economic boom in the monastery, which carried out building work on a large scale. The enclosure building was almost completely redesigned and finally the monastery church was refurbished at the end of the 15th century. The Marienkapelle was built at the beginning of the 16th century.

reformation

The 16th century brought turmoil, the peasant revolts and finally the introduction of the Reformation in the monastery. During the term of office of Abbot Alexius Borrenfurer , his prior, the later Württemberg reformer Ambrosius Blarer , left the abbey in 1522 . After the re-conquest of his duchy, Duke Ulrich von Württemberg occupied the monastery and reformed it in 1534. The abbot Ulrich Hamma could not oppose him and resigned. In 1535 the duke abolished the Alpirsbach monastery.

During the phase of the Augsburg interim from 1548 to 1555, the church property had to be returned to the Benedictine monks under Abbot Jakob Hochreutiner, who raised the tower by a bell storey with a stepped gable. However , the peace of Augsburg in 1555 meant that the monastery again fell to the Evangelicals. In 1556, Duke Christoph set up a monastery school in Alpirsbach like in the other thirteen male monasteries in the country. However, this was already canceled again in 1595 and merged with the school in Adelberg .

In the course of the Thirty Years' War , as a result of the Edict of Restitution from 1629–1631 and from 1634–1648, monks from the imperial abbey of Ochsenhausen returned to the monastery. In the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Alpirsbach finally came to the Duchy of Württemberg and, as before, was administered as an independent monastery office. In 1649 the Leutkirche is demolished. The prelate was the legal successor of the Catholic abbot with a seat in the state parliament, he was supported by a monastery administrator. In the years 1807–1811, the church property, which had been administered separately up to this point in time, was transferred to the property of the Kingdom of Württemberg, and the monastery office was incorporated into the Oberamt Oberndorf . Alpirsbach lost its function as court and administrative seat.

Property of the monastery

The founding estate of the monastery was relatively closed around Alpirsbach, little was added in the following period, free float is recognizable around Haigerloch, Oberndorf , Rottweil, Sulz and Nordweil . In 1355 the two villages of Gosheim and Wehingen were acquired by the Reichenau monastery. The land ownership was organized as a manorial lordship, in the late Middle Ages the monastery property was divided into benefices , the abbey was heavily in debt in the second half of the 15th century. The consolidation at the end of the Middle Ages also affected the economic situation.

Bailiwick

The legal institute of the Bailiwick corresponded to a high, low and manorial jurisdiction of the monastery . Hereditary monastery bailiffs were the Counts of Zollern, probably the Dukes of Teck from the middle of the 13th century , and probably the Counts of Württemberg from the end of the 14th century. The latter promoted the reform efforts of the monastery in the 15th century, u. a. with the aim of a rural monastic community. State rule and the Reformation brought about the end of the Catholic abbey (1535).

Building history

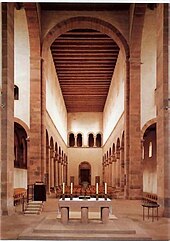

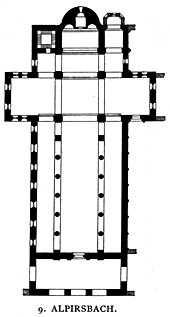

A small monastery as a foundation with a wooden oratory (1095) was soon followed by a small stone church (1099), and finally the completion of the cathedral building in the form of a flat-roofed three-aisled basilica with transept, choir and side choirs (1125–1133), which was consecrated to St. Nicholas in 1130 .

The floor plan of the monastery is based on the Benedictine monastery building scheme and shows the characteristics of the Cluniac reform monasteries, which were conveyed in Germany via Hirsau Monastery . Alpirsbach is an example of the Hirsau construction school .

Cluniac Reform

Characteristic for all buildings of the Cluniac reform : archaic attitude, clear manageability of the floor plans, expansiveness outside and inside, abandonment of the west choir and the crypts , the vault construction and the limitation of the plastic decoration. The model for this was the second columned basilica in Cluny (Cluny II) , consecrated in 981 . By changing the liturgy , the veneration of saints had increased dramatically - every priest had to read a mass every day - and as a result the part of the church reserved for the priesthood had to be expanded. Cluny's basic idea shines through everywhere in the reform churches. The hierarchical order of the convent found visible expression in the design of the monk's church . It was divided into three parts with different meanings for worship:

- The altar house, called the presbytery by the Cluniacens , was reserved exclusively for service at the altar. In addition to the high altar , there were altars in the three niches of the massive substructure of the main apse, and another, a special form in Alpirsbach. The accumulation of the altars in the main apse is explained by the order of the Cluniac, which stipulates that certain masses, e.g. B. funeral masses were not allowed to be celebrated at the high altar.

- In the crossing of the transept, the chorus maior, was the place of the priests who took part in the choir singing.

- This was followed by the chorus minor, already in the east yoke of the ship and marked there by the creation of pillars (in contrast to the other columns) and separated by a barrier from the lay church, in which those monks sat who did not attend the service due to age, frailty or illness could contribute. The transept wings were assigned to the lay brothers.

The east towers were to the east of the transept, flanking the sanctuary (Swabian tradition), which served to coordinate liturgy and bells. The middle apse is semi-circular on the outside; Above the three altar niches - as in Hirsau - a kind of tribune for a fourth altar, in the west a flat-roofed paradise . The unusual height of the church interior corresponds to that at the beginning of the 12th century. incipient increase in proportions in the preliminary phase of the Gothic. Heavy cube capitals indicate the Swabian preference for rough shapes.

The monastery is attached to the church, which faces east-west. The chapter house dates from the 12th century, the cloister and enclosure were built from 1480–1495. In the east is the dormer building with the bedrooms on the upper floor and the work and common rooms of the monks. In the south, the Kalefaktorium and the refectory with kitchen are connected. To the west is the storage area with storage cellars and access to the outside world via the gate.

In the 15th century extensive renovations took place on the east wing of the enclosure. The dorment area was divided into individual elements. The cloister was raised so that cells could also be accommodated on the upper floor. At the same time, a new refectory was created in the south building.

Noteworthy elements of the monastery are the tympanum above the west portal (12th century), the 4 meter high monolith columns in the nave are also a special feature. The column capitals of the eastern columns have heads with ribbon ties or dragon-like beings, which probably symbolize the conflict between heaven and hell. The massive Romanesque pews in the side aisle, a ( turner's work from around 1200), a high altar shrine (approx. 1520) and epitaphs, etc. a. Alpirsbach abbots are further outstanding achievements.

Organ of the monastery church

The organ of the monastery church was built in 2008 by the organ builder Claudius Winterhalter . The instrument has 35 registers on three manuals and a pedal . The second manual (solo work) is generated from the main work via alternating loops . The alpine flute in the main work is striking as a horizontal register. The pedal has four extended registers. It is particularly noteworthy that the instrument can be moved inside the church.

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Coupling : II / I, III / I, III / II, I / P, II / P, III / P, II 16 ′ / II, II 4 ′ / P

gallery

Tympanum above the west portal - Christ as world savior, enthroned in mandorla on a rainbow. Originally painted in color

Capital with Hirsauer nose

List of Abbots from Alpirsbach

- Cuno, probably from St. Blasien (1095–1114)

- Konrad, 1117 to 1127

- Berthold I., from 1127

- Ebirhardus, († 1173)

- Conradus, († 1178)

- Trageboto, († 1186)

- Burkart I., 1186 to 1222

- Dietrich, 1231

- Berthold II, 1251

- Berthold III., 1251 to 1266

- Burkart II, 1266 to 1271

- Volmar, probably from the von Brandeck family , († before February 1, 1271)

- Johann I (1297 to 1299)

- Albrecht I, (1299)

- Walter Schenk von Schenkenberg , (1303–1336, † August 12, 1337)

- Brun Schenk von Schenkenberg (1337-1377; † before 1380) in his tenure, the Kniebis monastery submitted in 1341 , but the free choice of a prior was still granted.

- Johann II., Von Sulz (1380, 1381)

- Konrad III., Of Gomaringen , (1383, † 1396)

- Bruno II. (1393 to 1396), (according to Martin Gerbert's list of abbots )

- Conrad IV., (1396 to 1397), (according to Martin Gerbert's list of abbots)

- Heinrich Hauk (1397–1414, † St. Lukas, 1414)

- Hugo von Leinstetten , (1415, † 1432), took part in the Council of Constance

- Peter Hauck, (1432 to 1446)

- Konrad Schenk von Schenkenberg, (1447, resigned 1450)

- Volmar II., Late, probably from the von Brandeck family, (1450 to 1455),

- Andreas von Neuneck (1455, 1456) he received the dignity of bishop (miter and staff) and wrote a chronicle which, however, in the possession of his descendants, was lost in the fire in Besenfeld in 1750 .

- Erasmus Marschalk von Pappenheim -Biberach (1470–1471)

- Georg Schwarz (1471– † April 14, 1479)

- Hieronymus Hulzing (1479– † May 17, 1495)

- Gerhard Münzer von Sinkingen , from Rottweil, (1495– † February 7, 1505)

- Alexius Barrenfurer (1505– † January 23, 1523), under him Ambrosius Blarer entered the monastery.

- Ulrich Hamma, (1523–1535, † before January 25, 1547), he was a conventual of the monastery and was determined by external election but with the consent of the convent. He had to lead the monastery through the turmoil of the Peasants' War .

- Jakob Hochreutner (1547 - resigned June 19, 1559), imprisoned in Maulbronn and Hohenurach in 1562, then back to Maulbronn, then fled to Speyer, Basel, Einsiedeln and Rheinau, lastly (1563) to St. Gallen to his brother.

Evangelical abbots from Alpirsbach

As in the other Württemberg monasteries, the prelates in Alpirsbach were appointed directly by the ducal government. The Duke had issued the Great Church Ordinance for this purpose.

- Balthasar Elenheintz (1563–1577), Duke Christoph built the Alpirsbach town hall during his tenure .

- Johannes Stecher (1577–1580)

- Matthaeus Vogel (1580–1591)

- Johann Konrad Piscarius (1592–1601)

- Johannes Esthofer (1601-1606)

- Daniel Schroetlin (1606-1608)

- Kaspar Lutz (1608-1609)

- Andreas Voehringer (Veringer) (1609)

- Alexander Wolfhart (1610-1624)

- Georg Hingher (1624–1626)

- Elias Zeitter (1627-1634)

- 33. Caspar Krauss from Pforzheim (1630–1638), Catholic, based on the Edict of Restitution

- 34th and last Catholic abbot, Alphons Kleinhans von Muregg (1638–1648), based on the edict of restitution.

- Johannes Cappel (1651–1662)

- Elias Springer (1662–1663)

- Johannes Baur (1663-1670)

- Joseph Cappel (1671–1675)

- Johannes Zeller (1675–1689)

- Johannes Crafft (1689–1695)

- Georg Heinrich Häberlin (1695–1699)

- Georg Heinrich Keller (1699–1702)

- Ernst Konrad Reinhardt (1702–1729)

- Herbert Christian Knebel (1730–1749)

- Johann Albrecht Bengel (1749–1752)

- Gottlieb Friedrich Roesler (1752–1766)

- Johann Gottlieb Faber (1767–1772)

- Johann Christian Storr (1772–1773)

- Johann Christoph Schmidlin (1773–1788)

- Wilhelm Christoph Fleischmann (1788–1797)

- Johannes Friedrich (1797)

- Ernst Bernhard (1797–1798)

- August Friedrich Boek (1798–1804)

- David Bernhard Sartorius (1804-1806)

Todays use

The Alpirsbach monastery is open for tours. It is one of the state's own monuments and is looked after by the “ State Palaces and Gardens of Baden-Württemberg ”. The monastery church is available to the Protestant parish for their services, the Catholic parish uses a hall on the south side as a chapel.

See also

literature

- Alpirsbach. Edited by the Baden-Württemberg State Monuments Office (= research and reports on the preservation of buildings and art monuments in Baden-Württemberg, Vol. 10): Textbd. 1: History of founding, construction and equipment of the monastery, Textbd. 2: Late Middle Ages, Reformation and Urban Development. Stuttgart 1999

- Günter Bachmann: Alpirsbach Monastery. Deutscher Kunstverlag Munich / Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-422-03063-8

- Germania Benedictina, Vol. 5: The Benedictine monasteries in Baden-Württemberg. Arranged by Franz Quarthal . Ottobeuren 1976, pp. 117-124

- Karl Jordan Glatz: History of the Alpirsbach Monastery on the Black Forest . Strasbourg 1877 Digitized ÖNB Vienna .

- Dietrich Lutz: 900 years Alpirsbach Monastery. Report on the colloquium "Alpirsbach 1095-1995: On the history of monastery and town" on May 19 and 20, 1995. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. 24th year 1995, issue 4, pp. 207-218 doi : 10.11588 / nbdpfbw.1995.4.13972

- Anja Stangl: 900 years of Alpirsbach Abbey. In: Denkmalpflege in Baden-Württemberg , Vol. 24, 1995, Issue 1, pp. 3–8 doi : 10.11588 / nbdpfbw.1995.1.13331

Web links

- Official website for Alpirsbach Abbey

- Alpirsbach Monastery in the database of monasteries in Baden-Württemberg of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives

- Alpirsbach Abbey in cultural studies online

- Baden-Württemberg State Archive

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wirtemberg document book . Volume I, No. 254. Stuttgart 1849, pp. 315-3117 ( digitized version , online edition )

- ↑ Oberfinanzdirektion Karlsruhe State Palaces and Gardens (ed.): Monks and Scholars . Finds from 900 years of Alpirsbach Abbey. Regional Finance Directorate Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe 1995. , p. 10.

- ↑ Sigrid Müller-Christensen: Old Furniture, From the Middle Ages to Art Nouveau , Munich 1988 (1st edition 1948), p. 11

- ↑ Information on disposition

Coordinates: 48 ° 20 ′ 46 ″ N , 8 ° 24 ′ 15 ″ E