Lüne Monastery

The Lüne Monastery is a former Benedictine monastery and today's Protestant women's monastery in the city of Lüneburg in Lower Saxony . It is one of several monasteries administered by the Hannover Monastery Chamber. The current abbess is Reinhild Freifrau von der Goltz .

The monastery, founded in 1172, soon established itself as a wealthy and autonomous local power in the Lüneburg Heath . It recruited its nuns mostly from the influential Lüneburg patrician families and housed up to 60 women for most of its existence. They received training in Latin , the liberal arts, and Christian teaching and liturgy . In the course of the 15th and 16th centuries, the structure of the monastery changed first with the monastery reform of 1481 and later with the Reformation .

architecture

In 1380 the monastery was rebuilt in brick Gothic after a major fire . The cloister , the single-nave church from 1412 and the nuns' choir are well preserved, as is the former dormitory (bedroom).

inside rooms

In the church there is a picture from the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder on the altar of the nuns' choir . The high altar triptych (carved altar) was created in the early 16th century. Wall paintings from around 1500 in the monastery refectory are worth mentioning .

Summer refectory ( Remter ), restored in the style of the 16th century

history

Foundation and early history

The Lüne monastery founded a small community in 1172, which consisted of a maximum of 10 noble women from Nordborstel . Under the leadership of Hildeswidis von Marcboldestorpe, the group was allowed to move into an empty chapel, which was built in 1140 as a hermitage for a monk from Lüneburg. The founding deed was signed by Hugo as Bishop of Verden , Heinrich the Lion as Duke of Saxony and Bavaria and Berthold II as abbot of the St. Michael monastery in Lüneburg . The monastery was consecrated to St. Bartholomew and kept part of the apostolic robe as the main relic of the monastery. Although the monastery did not initially follow any specific monastic rule, it adopted the Benedictine rule in the course of the 13th century . The original monastery buildings burned down twice (1240 and 1372) and were then rebuilt closer to the city of Lüneburg.

In the course of the 13th century the monastery grew to a number of up to 60 nuns. They were mainly recruited from surrounding noble families and from the Lüneburg patrician families . To cover the general cost of living, the monastery was primarily dependent on the annual income from the Lüneburg saltworks , which it had owned as a Pfannherrschaft since 1229 . In 1367 the community had become so influential and wealthy that it openly rejected its papally appointed provost Aegidius von Tusculum, a powerful cardinal bishop , and instead chose its own candidate, the lesser known Konrad von Soltau. In the end, both parties agreed on a third candidate, Johannes Weigergang, and Pope Urban V granted the nuns the privilege of electing their own provost. Since the premodern women's convents relied on a male provost to represent the community's political and economic interests externally, this privilege of free choice meant the highest degree of autonomy that the monastery could attain. In 1395, the Lüne provost was awarded full sacramental care for the nuns, so that the monastery was now de facto both secularly and spiritually autonomous.

Monastery reform of 1481

The 15th century brought church reforms with it. The reform movement took hold in northern Germany in the early second half of the century. The rising reform theologians saw the rich and influential monasteries of the north as deviants from the original, legitimate doctrine of Christianity, especially from the ideal of poverty. Their interference in the secular sphere and a decline in Latin education were also criticized. In most of the cases studied, however, the production of Latin documents in the women's convents shows no signs of the alleged decline in education. Lüne Abbey joined the Bursfeld Congregation in 1481 and took in the provost and seven nuns from the nearby, already reformed Ebstorf monastery . The provost, Matthias von dem Knesebeck , deposed the prioress Bertha Hoyer and her subprioress. Instead, he made his own candidate, the former Ebstorf nun Sophia von Bodenteich, prioress.

The reform included an optimized curriculum for Catholic teaching, a revised liturgy in line with the reform, and a centralized and communal consumption of daily meals. This should increase the isolation of the monastery from the outside world and make it easier to control the need to avoid meat on Friday and during Lent . Refraining from meat posed a major logistical difficulty, as both the kitchen and the refectory had to be rebuilt. As a result, the monastery was integrated into a dense network of Reformed North German women's monasteries and their committed provosts, which became a regional power within North German church politics.

Lutheran Reformation

The territorial fragmentation of political sovereignty in Germany at the beginning of the 16th century pushed the individual sovereigns into the position of the official decision-maker regarding the acceptance or rejection of the Reformation . The monasteries feared for their survival as the new movement sought the secularization and expropriation of what they saw as an expression of decadence and separation from believers in the world. The Lüne monastery was in the area of the Duchy of Braunschweig-Lüneburg , which in 1519 had been the main venue of the Hildesheim collegiate feud . The feud led to a large debt of Braunschweig-Lüneburg and thus to the weakening of the monasteries. When many German territories were confronted with peasant uprisings in 1525 , Duke Ernst the Confessor tried to consolidate his budget quickly by sending a demand of over 28,000 guilders to all monasteries in Braunschweig-Lüneburg, which he threatened to enforce with a military show of force if necessary. Duke Ernst soon publicly confessed to the Reformation and thus also targeted the Roman Catholic monasteries directly. The women's convents of Braunschweig-Lüneburg, which have been closely linked since the monastery reform of 1481, resisted the Duke's demands, so that the situation was practically stalemate for the next four years. In the course of the introduction of the Reformation in the Principality of Lüneburg , at the instigation of Duke Ernst the Confessor, against the resistance of the nuns, the service was celebrated in German for the first time on April 26, 1528. In fact, at the end of 1529, the Lüner provost Johannes Lorber resigned from his post and made room for a ducal administrator, Johannes Haselhorst, and a Protestant preacher, Hieronymus Enkhusen. In 1529 the provost property was placed under the ducal administration and a new provost appointed by the sovereign was appointed to ensure the implementation of Lutheran teaching. In 1530 a new monastery order followed, which drastically changed the liturgy within the monasteries and abolished all religious vows . The women's communities were explicitly named as the new religious enemies. In 1531 one of the ducal tax collectors went so far as to destroy one of the chapels of the Lüne monastery, which was consecrated to St. Gangolf . When the prioress Mechthild von Wilde died in 1535, the nuns' resistance to the Reformation began to falter. Although the monastery was able to independently elect a new Catholic prioress, Elisabeth Schneverding, they accepted her incorporation into the Duke's Protestant sovereignty . Duke Ernst, on the other hand, surprisingly accepted that the monastery should be preserved and did not dissolve the institution as a whole. Due to the considerable resistance of the nuns, however, it took the convent to fully adopt the Reformation doctrine by 1562. However, due to a regulation in the Lüneburg monastery order, the monastery retained its independence. The Lüne office was formed from the confiscated provost goods of the monastery .

The monastery as a women's monastery

Externally, Lüne Monastery has been treated as a purely secular retirement institution since 1535. Internally, the monastery community continued to lead a devoted spiritual life in the Benedictine tradition. In 1711, at the instigation of Duke Georg Ludwig von Braunschweig-Lüneburg, the monastery was converted into a Protestant women's monastery , whose primary goal was to care for unmarried daughters of the Lüneburg nobles.

In 1793, during the First Coalition War , in which the Electorate of Hanover took part on the side of the anti-French coalition, a French army marched by nearby. The abbess , Artemisia von Bock, feared an imminent occupation of the monastery and quickly sold a large inventory of works of art, manuscripts and books from the library. Some of them came into private ownership and some into the custody of larger archives and depots nearby. During World War II , many of these archives fell victim to Allied air raids . Works of art and manuscripts also disappeared in the turmoil at the end of the war when the German administrative structures collapsed.

List of the above of the Lüne monastery

The lists below contain the above from the Lüne monastery.

|

|

|

Historical environment and its exploration

Women who entered the monastery did not break contact with their families of origin. The nuns lived in two families as they felt a bond with their biological family as well as with their newly found sisters in the monastery. The family connections between the nuns and the Lüneburg patrician families have largely been reconstructed today and show a deep connection between the monastery and city politics. The constant contact with relatives in the outside world is documented in around 1800 letters in Latin and Low German , especially from the 15th and 16th centuries. The late medieval letter collection from Lüner Benedictine nuns was found in a chest in the monastery archive at the beginning of the 21st century and has been evaluated by historians since around 2016. A digital edition of the letter collection has been published since 2016 in the form of a digital project by historians Eva Schlotheuber , Henrike Lähnemann and others. The letters offer a comprehensive and detailed insight into the life and work of the nuns in the late Middle Ages, especially through the effects of the Reformation.

Literacy and education

The amount of manuscripts that have survived that were written within the monastery walls suggest that the nuns were thoroughly trained in Latin , the liberal arts and theology. The standard of education was not limited to the monastery management, but extended to every novice who entered the monastery and was guaranteed by its own monastery school . For the nuns, the central purpose of education was the proper execution of the liturgy, which had to be sung in Latin. In their letters they presented themselves as the brides of Christ and dedicated their lives to the service of God as wives in the vineyard of the monastery. Your personal and official correspondence was only recently read back.

The letters between the monastery and its secular contacts, such as the city of Lüneburg or the monastery property, were written in Middle Low German , which functioned as an economic lingua franca within northern Germany and around the North and Baltic Seas as the main trading areas of the Hanseatic League . Mixed forms between Latin and Middle Low German were mainly used in the correspondence between the monasteries.

Textile museum of the Lüne monastery

Lüne is famous for its knitting and embroidery work (wool on canvas). Valuable pieces ( white embroidery , altar ceilings, Lenten cloths and carpets ), the oldest from around 1250. The textiles are exhibited in the Textile Museum, which opened in 1995 on the grounds of the monastery. Including the Sibylle and Prophet Carpet, the Root Jesse Carpet and the Miracle of Resurrection Carpet. The Easter carpet was sold to the Hamburg Museum of Art and Industry in 1948 .

literature

- Carl Ludwig Grotefend: The influence of the Windesheimer Congregation on the Reformation of Lower Saxony monasteries in: Journal of the historical association for Lower Saxony. 1872, pp. 73-88.

- Ernst Nolte: Sources and studies on the history of the nunnery Lüne near Lüneburg. Vol. 1: The sources. The history of Lünes from its beginnings to the renewal of the monastery in 1481 (Studies on the Church History of Lower Saxony 6) . Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1932.

- Hans-Jürgen von Witzendorff: Family tables of the Lüneburg patrician families . Göttingen, Reise, 1952.

- Urbanus Rhegius : Radtslach to nodtroft the monastery of the förstendom Lüneboch, Gades word and ceremonies concern . EKO . 6 (1), 1955, pp. 586-608.

- Ulrich Faust (Ed.): Germania Benedictina . Vol. 11: The women's monasteries in Lower Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein and Bremen . St. Ottilien: Eos, 1984.

- Heinrich Schmidt: Church regiment and state rule in the self-image of Lower Saxony princes of the 16th century . Lower Saxony Yearbook for State History 56, 1984, pp. 31–58.

- Martin Tamcke: The reformatic impulses for education and faith in Duke Ernst and in the Uelzen of his time (White Row 6) . Uelzen, 1997, Becker.

- Christine van den Heuvel , Christine; Martin von Boetticher: History of Lower Saxony . Vol. 3 (1): Politics, economy and society from the Reformation to the beginning of the 19th century , Hanover, 1998, Hahnsche Buchhandlung .

- Jens-Uwe Brinkmann: Lüne Monastery (= The Blue Books ) With photos of Jutta Brothers. Langewiesche, Königstein im Taunus 2009, ISBN 978-3-7845-0829-0 .

- Volker Hemmerich: Lüne Monastery. The medieval building history, Petersberg: Imhof 2018, ISBN 978-3-7319-0786-2 .

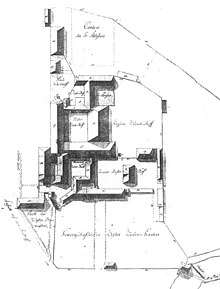

- Hans-Cord Sarnighausen: An old site plan of the monastery and office of Lüne. In: Heimatbuch for the district of Lüneburg. Vol. 6, 2007, ZDB -ID 2438387-9 , pp. 22-31.

- Doris Böker, Stefan Winghart (ed.): Architectural monuments in Lower Saxony. Vol. 22.1: Hanseatic City of Lüneburg: with Lüne Monastery (monument topography Federal Republic of Germany) . Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2010.

- Wolfgang Brandis: On the Reformation history of the Lüneburg convents. In: Jochen Meiners (Ed.): Setting an example: 500 years of the Reformation in Celle. Accompanying volume to the exhibition of the same name in the Bomann Museum in Celle, in the Residenz Museum in the Celle Castle and in the St. Marien town church . Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2007, 38-53.

- Josef Dolle, Dennis bonehauer (ed.): Lower Saxony monastery book. Directory of the monasteries, monasteries, comedians and beguinages in Lower Saxony and Bremen from the beginnings to 1810 . 4 vols. Bielefeld: Publishing House for Regional History, 2012.

- Jeffrey F. Hamburger , Eva Schlotheuber , Susan Marti, Margot Fassler: Liturgical Life and Latin Learning at Paradies bei Soest, 1300-1425: Inscription and Illumination in the Choir Books of a North German Dominican Convent. Aschendorff Verlag, Münster 2017.

- Henrike Lähnemann , Eva Schlotheuber, Simone Schultz-Balluf, Edmund Wareham, Philipp Trettin, Lena Vosding, Philipp Stenzig (eds.): Networks of the nuns. Edition and cataloging of the collection of letters from Lüne Monastery (approx. 1460–1555). Wolfenbütteler Digital Editions, Wolfenbüttel 2016 ( [1] ).

- Henrike Lähnemann: The Medinger Nuns War from the perspective of the monastery reform. Spiritual self-assertion 1479-1554 . In: Kees Scheepers ao (ed.). 1517-1545: The northern experience. Mysticism, art and devotion between Late Medieval and Early Modern. Antwerp Conference 2011 . Ons Geestelijk Erf . 87: pp. 91-116.

- Lena Vosding: Gifts from the convent. The letters of the Benedictine Nuns at Lüne as the material manifestation of spiritual care . In: Marie Isabel Matthews-Schlinzig; Caroline Socha (Ed.): What is a letter? Essays on epistolar theory and culture / What is a letter? Essays on epistolary theory and culture . Würzburg, 2018, Königshausen & Neumann, pp. 211–233.

- Sabine Wehking: The inscriptions of the Lüneburg monasteries. Ebstorf, Isenhagen, Lüne, Medingen, Walsrode, Wienhausen (The German inscriptions 76). Wiesbaden, 2009, Reichert. ( Online open access on inschriften.net )

- Eike Wolgast: Reformation from above. The establishment of an evangelical authority 1526-1580 . In: Wartburg Foundation (ed.). Luther and the Germans: Accompanying volume for the national special exhibition at the Wartburg, May 4 - November 5, 2017 . Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, pp. 38-43.

- Eva Schlotheuber: Doctrina privata and doctrina publica - reflections on medieval women's convents as a space for knowledge and education . In: Gert Melville (ed.). The power of monastic life in the Middle Ages. Models - orders - competencies - concepts (monasteries as innovation laboratories. Studies and texts 7) . Regensburg: Pustet, 2019.

Web links

- Site of Lüne Monastery

- Lüne Monastery in the Lower Saxony Monument Atlas

- Edition project "Networks of Nuns. Edition and indexing of the collection of letters from Lüne Monastery (approx. 1460-1555)"

- Description of Lüne Monastery on the Lower Saxony monastery map of the Institute for Historical Research

- Digital edition of the Lüne Monastery letter collections

- The Nuns' Network: Project Presentation , lecture on the Lüne Monastery collection of letters by Henrike Lähnemann , Edmund Wareham and Konstantin Winters (English), YouTube video (37:27 minutes)

- Inscriptions and pictures of the Lüne monastery in the Lüneburg Monasteries catalog

Individual evidence

- ↑ orden-online.de

- ↑ Article on the architectural history of the monastery

- ↑ Lüne - monastery treasures kloster-luene.de.

- ↑ Nolte, Quellen (1932), 120–126.

- ↑ The saint is depicted on the seal of the monastery, cf. Reinhardt, Art. Lüne, in: Germania Benedictina 11, 393.

- ^ Boker; Winghart (Ed.), Baudenkmale (2010).

- ↑ Grotefend, The Influence (1872), 73-88.

- ^ Hamburger , Eva Schlotheuber , Marti, Margot Fassler, Liturgical Life (2017), 92-96.

- ^ Nolte, Quellen (1932), 127-128.

- ^ Nolte, Quellen (1932), 128.

- ↑ Wolgast, Reformation (2017), 39.

- ^ Schmidt, Church Regiment (1984)

- ↑ Tamcke, Impulse (1997), 242.

- ↑ Brandis, Zur Reformationsgeschichte (2017), 43.

- ↑ Rhegius, Radtslach (1530).

- ↑ Brandis, Zur Reformationsgeschichte (2017), 41.

- Jump up ↑ Dolle, beinhauer (ed.): Monastery book. Volume 2, 2012, pp. 940-946.

- Jump up ↑ Dolle, beinhauer (ed.): Monastery book. Volume 2, 2012, pp. 946-947.

- ^ Witzendorff, Family Tables (1952).

- ↑ Historical letters: Insight into the life of nuns at ndr.de from February 5, 2020

- ↑ Henrike Lähnemann , Eva Schlotheuber et.al. (Ed.): Networks of the Nuns (2016–) online edition ( diglib.hab.de ).

- ^ Source research in the 21st century. Colloquium for the 200th anniversary of MGH ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica ), Munich 2019.

- ^ Networks of the nuns. Edition and indexing of the collection of letters from Lüne Monastery (approx. 1460-1555). In: Wolfenbütteler digital editions. Wolfenbüttel 2016-, online .

- ^ Schlotheuber , Doctrina (2019).

- ^ Matthias Gretzschel: A picture book of medieval piety. In: Hamburger Abendblatt , August 22, 2014, p. 15.

Coordinates: 53 ° 15 ′ 37 ″ N , 10 ° 25 ′ 20 ″ E