Monastery garden

A monastery garden is a garden in connection with a monastery . The medieval monastery garden was originally a kitchen garden for the purpose of monastic self-sufficiency . The design was influenced by Christian symbolism and world interpretation . The monastery garden played an important role in the development of botanical and medicinal science into scientific disciplines. The monasteries took their gardens significant influence on the cultivation of plants, their distribution in the natural and cultural landscape and their use in nutrition, medicine, worship and daily life. Today's "medieval" monastery gardens are reconstructions based on a few written and pictorial sources and isolated archaeological findings.

Origin and plant

The Roman country villas are models for the gardens of the monasteries that were built in the late antiquity . Here as there, vegetable and tree cultures were used for self-sufficiency. The monastic self-sufficiency with the help of a garden was already given in the Benedictine rule written in the 6th century :

"Monasterium autem, si possit fieri, ita debet constitui ut omnia necessaria, id est aqua, molendinum, hortum, vel artes diversas intra monasterium exerceantur."

"If possible, the monastery should be laid out in such a way that everything necessary, namely water, mill and garden, is located within the monastery and various types of handicraft can be practiced there."

Up to the end of the Middle Ages, the gardens were designed more simply, often with a rectangular floor plan, in which rows of beds were laid out and bordered with wickerwork or boards (especially for raised beds ). Next to this kitchen garden for herbs and vegetables there was usually a tree garden . In the Carthusian monastery , each monk kept his own little garden within the walls of his little cell house because of the reclusive way of life. Food crops that were needed in large quantities, such as peas, beets and cabbage, were grown on estates outside the monastery. For this purpose, forests were cleared on a large scale, especially by the Cistercians , who, together with the Benedictines, played a major role in the renewed horticulture and lived far from other settlements. The reclamation of new land by monasteries ensured the further spread of plants grown in the monastery gardens, which escaped from there and became naturalized in the wild flora.

Since the High Middle Ages, there have also been an increasing number of ornamental or pleasure gardens in monasteries , lawns that are not used for economic purposes and are used for peace and prayer. Albertus Magnus explains in his work De vegetabilibus (Lib. VII, I, 14: De plantatione viridariorum ) the creation of a combined herb and ornamental garden; The latter takes up the greater part of the complex, there is a contained spring, a row of trees as a boundary and ornamental plants such as Madonna lily , rose , iris , columbine , violet , sage , basil , rue and hyssop . However , parks outside the clerical area that were dedicated to the actual garden art did not emerge until the Renaissance and Baroque periods .

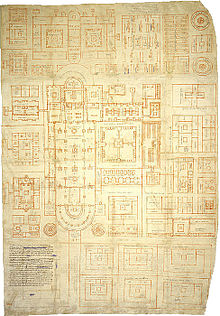

Little contemporary information is available on the layout of the monastery gardens and hardly any archaeological findings are available. Some conclusions can be drawn from paintings and pictures in books of hours or tapestries in Mille Fleurs pull -designing. The most important are the St. Gallen monastery plan from the early 9th century and the poem Liber de cultura hortorum (“Book about horticulture”) from the year 827 by Walahfrid Strabo , abbot of Reichenau monastery, also just Hortolus (“little garden”) ) called. The Carolingian ordinance for the management of the imperial estates and manor houses from the year 812, the Capitulare de villis vel curtis imperii , with its extensive list of 73 flowers, herbs, vegetable and fruit plants and 16 trees, is likely to have a significant influence on the Hortolus and St. Gallen to have. According to these specifications, so-called Charles Gardens are still being planted today .

The monastery garden in Braunschweig was opened in the 2000s .

Religious meaning

The plants of the monastery gardens found their way into the books that were produced in the scriptoria and appeared in stylized form as decorations next to the text. On the other hand, in the monastery garden, where both contemplation and handicraft work took place, Christian symbolism and interpretation of the world were always present. The rules of the order charged manual labor with the aspect of salvation that carried over to the object of work. With their vegetation rhythm (flowering, fruit ripening, winter dormancy and renewed blooming), the fruit trees were a symbol of the resurrection, the tree garden therefore often served as a monastery cemetery . Evergreen plants ( ivy or rosemary ) also refer to eternal life. The cultivated plants were given Christianized names that took the place of the popular names that were occasionally rejected because of their pagan origin: Georgenkraut instead of valerian , St. John's wort or Jageteufel instead of hard hay. Plant names such as lady's slipper or lady's mint are derived from the invocation of Mary as "Our Lady".

The Mother of God is often shown on altarpieces or carpets in the Hortus conclusus (“closed garden”). There, white Madonna lilies symbolized their virginity and purity, the thornless rose their inexhaustible mercy , grace and gentleness. The image of the closed garden goes back to a passage in the Song of Songs related to the Virgin Mary:

"Hortus conclusus soror mea sponsa hortus conclusus fons signatus."

"A closed garden is my sister and bride, a closed garden and sealed spring."

The Hortus conclusus represented the earthly paradise , outside of which the enclosure is the desperate world. The idea of the Garden of Eden lost through the fall of Adam and Eve and reopened through Christ was connected with Mary as Mother of God . Mary is often represented in the company of a unicorn , who embodies the incarnate God and is supposed to cancel out the effects of poison with his horn, just as Christ overcame original sin. The ornamental and tree gardens of the monasteries were obviously the inspiration for the presentation of the Hortus conclusus. For these gardens, Albertus Magnus recommended plants such as Madonna lily, rose, iris , columbine , violet , sage , rue or hyssop , which were placed in relation to Mary or to church and cult (for example as altar decorations or as attribute plants at holy festivals). Many of the plants grown in the monastery garden, such as St. John's wort ("Jageteufel"), mugwort or thistles also fulfilled apotropaic functions , in that they were supposed to help deny access to dark forces or to exorcise demons and sorcery. A similar effectiveness was seen in the cross-shaped routing to the bedding.

Herbal and medicinal science

The monks collected works by ancient authors on herbal and medicinal science , reproduced them and built on this knowledge. They wrote their own papers, and there was a lively exchange of books, plants, preparations and seeds between the monasteries. In this way, and through long-distance trade, a number of southern European and oriental plants came to the central European and northern alpine regions. There, a protected location within or along the monastery walls made it possible to cultivate them and thus to gain in-depth knowledge of previously foreign plants such as fennel and lovage . Over time, the originally Mediterranean plants were not only planted in the monastery gardens, but also in civil and rural home gardens . The systematic differentiation of the different flora and greater botanical accuracy in the description of the species occurring in each case succeeded from the 16th century, parallel to the numerous herbal books that were emerging at that time . The botanical gardens , which also developed in the vicinity of the medical faculties at the universities and further advanced research, were clearly in the tradition of the monastery gardens, which had been enriched with exotic medicinal plants for teaching purposes.

Some orders were primarily or entirely devoted to medieval monastic medicine . The Antonites or the Order of Lazarus specialized in medical activity, and the Benedictines saw caring for their sick as a service to Christ himself.

“Infirmorum cura ante omnia et super omnia adhibenda est, ut sicut revera Christo ita eis serviatur.”

"Care for the sick must come first and foremost, so that one really serves them like Christ."

Especially strong-smelling plants were used in the medical field. The miasm theory , which has prevailed since ancient times, said that poisonous fumes from the earth were carried away with the air and thus spread diseases. In the hospices , the “polluted air” was fumigated, and fresh cut flowers exuded their scent on the floors of the monasteries and churches, which was said to have an invigorating and healing effect. The strong scent of roses and lilies was emphasized, while scentless flowers were ignored. Last but not least, the herbs from the Mediterranean region were very popular with doctors, pharmacists and the people because of their distinctive aromas.

The monks and nuns gathered experience in dealing with medicinal herbs and their effects. Oral traditions of folk medicine , which were included in the teaching, supplemented their own knowledge . The treatises by the Benedictine nun Hildegard von Bingen are famous for this . In some cases, previously known treatments were included, but some were completely new or not yet recorded in writing. The secular pharmacy , which had spread to the cities since the 14th century, created its own herb gardens and, with other public health facilities since the early modern period, has increasingly replaced the complex of monastery garden, pharmacy and hospice, drew from the monastic experiences .

literature

- Marilise Rieder: Small Klingental monastery garden - symbolism and use of garden plants in the Middle Ages. Museum Kleines Klingental, Basel 2002, ISBN 3-9522444-1-4 .

- Johannes Gottfried Mayer : Monastery medicine: the herb gardens in the former monastery complexes of Lorsch and Seligenstadt. Verlag Schnell and Steiner 2002, ISBN 978-3-7954-1429-0 .

- Johannes Gottfried Mayer: Monastery gardens - God's pharmacy In: Rudolf Walter (Hrsg.): Health from monasteries. Herder Verlag, Freiburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-451-00546-6 , p. 8ff.

- Irmgard Müller: Medicinal plants from monastery gardens. In: The legacy of monastery medicine: Symposium at Eberbach Monastery, Eltville / Rh. on September 10, 1977, text of the lectures. Ingelheim a. Rh. 1978, pp. 9-14.

Web links

- Doris Schulmeyer-Torres: Cottage gardens (extract)

- Turba Delirantium: Hortulus (information on horticultural and arable farming in the Middle Ages)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christina Becela-Deller: Ruta graveolens L. A medicinal plant in terms of art and cultural history. (Mathematical and natural scientific dissertation Würzburg 1994) Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1998 (= Würzburg medical-historical research. Volume 65). ISBN 3-8260-1667-X , pp. 104-110.