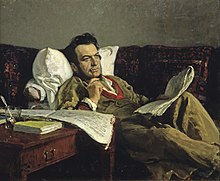

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka ( Russian Михаил Иванович Глинка , scientific transliteration Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka , also Mikhail Glink ; born May 20, jul. / 1. June 1804 greg. In Nowospasskoje , Smolensk , Russian Empire ; † 3 jul. / February 15 1857 greg. In Berlin ) was a Russian composer . He is considered to be the creator of an independent classical music in Russia .

Life

Mikhail Glinka was born in the village of Novospasskoye near Smolensk, the son of a nobleman. He spent the first six years of his life in the overheated room of his paternal grandmother, who tried to shield him from all external impressions. His first musical impressions were limited to the birdsong in his family's garden, the songs of his nanny and the piercingly loud church bells for which the Smolensk region was famous. After the death of his grandmother in 1810, he came into the care of his parents and finally had the opportunity to listen to other music. When, after about four years, he heard a clarinet quartet by the Finnish clarinetist Bernhard Henrik Crusell , this experience aroused his interest in music. In addition, he was influenced by the Russian folk music of a wind orchestra, which he heard at lunchtime festivities. A violinist from his uncle's music group gave him his first instructions on how to play the violin.

Around 1817 he began to study at the aristocratic institute of Saint Petersburg . He took three piano lessons with the Irish composer John Field , and when he met Johann Nepomuk Hummel on his trip to Russia, he made a positive impression on him. In 1823 he went on a trip to the Caucasus , where he was fascinated by the natural beauty and local customs, returned to his place of birth for six months and after his return to St. Petersburg in 1824 took an undemanding position as undersecretary in the Ministry of Transport. In his free time he expanded his circle of acquaintances and friends. The poet and man of letters Wilhelm Küchelbecker , who was exiled to Siberia after the Decembrist revolt on December 14, 1825 , introduced Glinka to the Russian national poet Alexander Pushkin . Glinka's connections to the well-known poet and the political turmoil of the time influenced the thoughts and actions of the later composer. From 1830 he went on a trip to Italy , where he was able to expand his knowledge of opera for three years . During this time he studied in Naples and met Vincenzo Bellini , Gaetano Donizetti and Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy in Milan . In 1833 he carried out further music studies with Siegfried Dehn in Berlin . When his father died in 1834, he returned to Russia.

In 1836 his opera A Life for the Tsar ( libretto by Baron Jegor Fjodorowitsch von Rosen ) was premiered in the Great Theater of Petersburg . It was the first Russian opera to be sung in Russian to achieve the status of a classic. The story tells of the heroic deeds of the farmer Ivan Sussanin , who is said to have lived in the time of turmoil at the beginning of the 17th century. According to legend, Sussanin led the Polish occupiers into impassable forests from which they could not find their way back. Shortly afterwards he was killed.

In Glinka's national opera, simple people like peasants play the leading role, which the members of the nobility did not like. Just in order not to arouse the tsar's displeasure , he did not choose the title Iwan Sussanin for his work , but A Life for the Czar . The opera was a great success, and Glinka was appointed Kapellmeister of the Petersburg Chapel .

His second opera Ruslan and Lyudmila followed in 1842 (libretto by Valerian Schirkow and Nestor Kukolnik ), which was based on a poem by Alexander Pushkin and is very popular. From 1844 he started traveling again, this time to Paris , where he often met Hector Berlioz , and the next year to Spain ( Valladolid , Madrid and Seville ). Here he was enthusiastic about the traditional music of Spain and wrote his First Spanish Overture , with the Jota aragonesa .

After further trips to Poland, where he absorbed the influence of Frédéric Chopin , and France, he set off on his last trip to Berlin in May 1856, where he resumed his counterpoint studies with Siegfried Dehn on works by Johann Sebastian Bach . After a concert in January 1857 in which Giacomo Meyerbeer conducted an excerpt from A Life for the Tsar , Glinka caught a cold and died three weeks later on February 15, 1857 in the Prussian capital.

Glinka was initially buried in the Berlin Trinity Cemetery in front of the Potsdamer Tor . However, in May of the same year he was transferred to the Tikhvin cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg. His original grave slab from the Trinity Cemetery , which Dehn had commissioned, is now part of a memorial for Glinka in the Russian cemetery in Berlin-Tegel .

Honors

The inscription on a memorial plaque at Französische Strasse 8 in Berlin-Mitte reads:

- IN WHICH BY WAR EFFECTS

- DESTROYED HOUSE IN THIS PLACE

- LIVED AND WORKED FOR THE LAST MONTHS

- OF HIS LIFE

- THE GREAT RUSSIAN COMPOSER

- MICHAIL GLINKA

- In Glinka's honor, the three Russian state conservatories in Nizhny Novgorod , Novosibirsk and Magnitogorsk as well as Glinkastrasse in Berlin-Mitte were named after him.

meaning

In order to understand the extent of Glinka's achievements, one must first consider the musical situation in Russia into which he was born. In the course of the 18th century, style influences from Western Europe had become dominant in Russian culture. Even the Russian folk song was not immune to foreign influences, because the city song developed in the cities , where the western influence was noticeable in regular rhythms and the increased use of sequences .

Glinka's most important legacy, however, does not lie so much in his stylized folk songs, but above all in his very personal, very Russian-influenced musical language, in which, in contrast to German music , he dispenses with the dissecting and combining implementation of small-scale themes and instead uses variations of longer melodic phrases composed.

Because of his style-defining influence, Glinka is known as the "father of Russian music".

Relationship to Judaism

In 1840 Glinka wrote an overture, three songs and four interludes for the play tragedy Prince Cholmski ( Knjas Cholmski ) by Nestor Kukolnik . The play takes place in Pskov in 1474 and revolves around the fight between Prince Kholmsky and the German Brothers of the Sword Order of Livonia . It mentions a Jewish conspiracy that wants to prevent the prince from fighting. The tragedy fell through with criticism after its premiere in September 1841 at the Alexandrinsky Theater in Petersburg , was canceled after three performances and then little received. Glinka's orchestral pieces were recorded in 1984 by Yevgeny Svetlanov for the Melodija label . The American musicologist Richard Taruskin describes the representation of the Jewish figures in the work as advantageous. One piece that Glinka later used in his cycle Farewell to Petersburg ( Proschtschanie s Peterburgom ) is about the Jewish girl Rachil who sacrifices herself for love. Glinka later noted that he had written it for a Jewish girl whom he fell in love with in Berlin in 1833.

In a CD review in the New York Times in 1997, Taruskin described the composer Mili Balakirew as an anti-Semite who wrote Jewish songs at the same time. These were published together with “Jewish songs” by the equally “zhidophobic” Modest Mussorgsky and Glinka. Elsewhere, Taruskin refers to a letter from Glinka from 1855, in which he describes the Jewish composer Anton Rubinstein as "Jews" (with the term "schid", which has been derogatory in Vladimir Dahl's dictionary since 1863), which is characterized by its cosmopolitan Position endanger the autonomy of Russian music. Taruskin emphasizes that Glinka's contemporary Modest Mussorgsky displayed his anti-Semitism much more strongly.

Works (selection)

Choral works

- Drinking song after Anton Antonowitsch Delwig , 1829

- Not the regular autumn shower, 1829

- Farewell song of the students of the Jekatarinsky Institute, 1840

- The Toast Song, 1847

- Farewell song of the schoolgirls of the Society for Higher Daughters, 1850

- The Braid, 1854

- Prayer in a difficult life situation, 1855

Piano works

- Cotillon, 1828

- Finnish song, 1829

- Cavalry trot, 1829/30

- Motif from a folk song

- Fantasy about two Russian songs

- Variations on "The Nightingale" by A. Aljabjew, 1833

- Gallopade, 1838/39

- Bolero, 1840

- Tarantella on a Russian folk song, 1843

- Greetings to my homeland, 1847

- Las mollares (based on an Andalusian dance)

- Leggieraments

- Nocturne "La Séperation"

Operas

- A Life for the Tsar , 1834–36

- Scene at the monastery gate , 1837

- Ruslan and Lyudmila , 1837–42

Incidental music

- Prince Cholmski , overture, three songs and four interludes for the dramatic tragedy Князь Холмский by Nestor Kukolnik , 1840

Chamber music

- String Quartet No. 2 in F major (1830)

- Trio Pathétique for clarinet (violin), bassoon (cello) and piano (1832)

- Sonata for Viola and Piano in D minor (incomplete) (1835)

- Sextet in E flat major (1842)

Orchestral music

- Andante cantabile and Rondo (1823)

- Kamarinskaja, Scherzo (1848)

- Overture in D major (1822-26)

- Overture in G minor (1822–26)

- Spanish Overture No. 1 (Caprice Brilliant on the Theme of the Jota Aragonesa) (1845)

- Spanish Overture No. 2 (Souvenir d'une nuit d'été à Madrid) (1848–51)

- Symphony on Two Russian Themes (1834)

- Polonaise in F Major on a Spanish Bolero Theme (1855)

- Waltz Fantasy in B minor (1839, 1845, 1856)

miscellaneous

Glinka's piano composition Motif de chant national was the national anthem of the Russian Federation from 1990 to 2001 under the title Patriotic Song .

Glinka's work Slavsja (Be Honored) has served as a template for one of the two melodies of the Kremlin curants since 1995 . It is noteworthy that the bells of the Kuranten are not enough to play the entire melody. Three additionally required tones are automatically created at the moment, the missing bells are still in production.

There is a Glinkastraße in Berlin-Mitte . There is a large wall relief with Glinka's head and the saying “It is the people who create the music. We musicians just arrange them ”. The relief comes from the sculptor Olga ("Olly") Waldschmidt . The asteroid of the main outer belt (2205) Glinka , discovered on September 27, 1973, was named after him. He has been the namesake of the Glinka Islands in Antarctica since 1961 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Michail Iwanowitsch Glinka in the catalog of the German National Library

- Sheet music and audio files by Michail Glinka in the International Music Score Library Project

- K. Kovalev: Glinka - the author of Russian national anthem . (English)

- Catalog of works on klassika.info

Individual evidence

- ↑ Victor L. Seroff: The mighty five - The origin of Russian national music . Atlantis Musikbuch-Verlag, 1963, 3rd edition, ibid. 1987, p. 12 ff.

- ↑ Montagu Montagu-Nathan: Glinka. Biblio Bazaar, 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ a b c d e f Clive Unger-Hamilton, Neil Fairbairn, Derek Walters; German arrangement: Christian Barth, Holger Fliessbach, Horst Leuchtmann, et al .: The music - 1000 years of illustrated music history . Unipart-Verlag, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8122-0132-1 , p. 112 f .

- ↑ Süddeutsche Musik-Zeitung . Vol. 6, No. 10, March 9, 1957, p. 1. Kurt Pomplun : Berlin houses. Stories and history . Hessling, Berlin 1971, ISBN 3-7769-0119-5 , p. 99. Detlef Gojowy: German-Russian music relationships. In: Dittmar Dahlmann, Wilfried Potthoff (Ed.): Germany and Russia . Aspects of cultural and scientific relationships in the 19th and early 20th centuries . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-447-05035-7 , pp. 191–236, here p. 194. Hans-Jürgen Mende : Lexicon of Berlin burial sites . Pharus-Plan, Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-86514-206-1 , p. 1006. In many representations there is confusion regarding Glinka's original burial place. The Russian Cemetery in Berlin-Tegel, the Trinity Cemetery I and the Luisenstadt Cemetery are mistakenly identified as places of burial in Berlin.

- ↑ MI Glinka Conservatory website , nnovcons.ru, accessed February 19, 2018. (Russian)

- ↑ conservatoire.ru ( Memento of the original from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ magkmusic.com

- ↑ Malte Korff: Tschaikowsky. Life and work. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-423-28045-7 , p. 16.

- ↑ Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka | Stage music for the play Prince Cholmskij | Incidental Music to Prince Kholmsky. Retrieved July 6, 2020 .

- ↑ The prince speaks of a "Jewish curse" ("schidowskoe prokljatie"), his fool of a "Jewish heresy" ("schidowskaja eres"). Nestor Kukolnik: Knjas Danil Wassiljewitsch Cholmski. In: ders .: Sotschinenija, Vol. 2. I. Fischon, Petersburg 1852. Online text in Russian.

- ^ Oskar von Riesemann: Monographs on Russian Music. Three masks, Munich 1923, p. 134.

- ^ M. Glinka *, Evgeni Svetlanov - Symphony On Two Russian Themes, Incidental Music To "Prince Kholmsky", Dances From The Opera "Ivan Susanin". Retrieved July 7, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Richard Taruskin: On Russian Music. University of California Press, Berkeley 2008, p. 196 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ The English word "the" does not clearly indicate in the overall context whether the attribute "zhidophobic" only applies to Mussorgsky or also to Glinka. The sentence reads in full: "It is included in this collection, along with 'Jewish Songs' by the equally zhidophobic Mussorgsky and Glinka."

- ↑ Richard Taruskin: RECORDINGS VIEW; 'Jewish' Songs By Anti-Semites . In: The New York Times . September 21, 1997, ISSN 0362-4331 ( nytimes.com [accessed July 7, 2020]).

- ↑ «Жид Рубинштейн взялся знакомить Германию с нашей музыкой и написал статью, в кокоторой всем музыкой и написал статью, в которой wrote one of our articles in Germany after: Boris Asafjew: Anton Grigorewitsch Rubinstein w ego muzikalnoj dejatelnosti i otzywach sovremennikow. Muzgiz, Moscow 1929, p. 61.

- ↑ Richard Taruskin: On Russian Music. University of California Press, Berkeley 2008, p. 198 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Kamarinskaya in the English language Wikipedia

- ↑ Stuart Campbell: Glinka, Mikhail Ivanovich. In: Grove Music Online (English; subscription required).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Glinka, Mikhail Ivanovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Glinka, Michail Ivanovič; Гли́нка, Михаи́л Ива́нович (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian composer |

| BIRTH DATE | June 1, 1804 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Novospasskoye , Smolensk Governorate , Russian Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 15, 1857 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Berlin |