Minamisōma

| Minamisōma-shi 南 相 馬 市 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Geographical location in Japan | ||

|

|

||

| Region : | Tōhoku | |

| Prefecture : | Fukushima | |

| Coordinates : | 37 ° 39 ' N , 140 ° 57' E | |

| Basic data | ||

| Surface: | 398.58 km² | |

| Residents : | 53,179 (April 1, 2020) |

|

| Population density : | 133 inhabitants per km² | |

| Community key : | 07212-5 | |

| Symbols | ||

| Flag / coat of arms: | ||

| Tree : | Japanese zelkove | |

| Flower : | Cherry Blossom | |

| Bird : | Skylark | |

| Fish : | Ketal salmon | |

| Insect : | Firefly | |

| town hall | ||

| Address : |

Minamisōma City Hall 2 - 27 Moto-machi Haramachi-ku , Minamisōma -shi Fukushima 975-8686 |

|

| Website URL: | www.city.minamisoma.lg.jp | |

| Location Minamisōmas in Fukushima Prefecture | ||

Minamisōma ( Japanese 南 相 馬 市 , - shi ) is a city in Fukushima Prefecture in Japan .

geography

The populated urban area was a nearly 10 km wide coastal plain bounded east by the Pacific Ocean and west by the Abukuma highlands ( 阿 武 隈 高地 , Abukuma-kōchi ). The latter largely uninhabited and heavily forested hilly landscape makes up about half of the area administered by the municipality.

The Fukushima coast differs from the further north lying Sanriku and Sendai coasts by different topographical and bathymetric features.

Minamisōma consists of three urban districts ( ku ), which go back to independent municipalities until 2005 and are therefore not grown together: Kashima-ku in the north, Haramachi-ku in the middle and Odaka-ku in the south. The direct coastal area is only sparsely populated and is mainly used for agriculture. The three settlement centers are therefore about 3–4 km inland.

Administratively, Minamisōma borders in the north on the independent city of Sōma , in the north-west on the village community Iitate and in the south-west and south on the small town of Namie . The closest major cities are Sendai in the north and Iwaki in the south, both around 75 km away.

history

The city of Minamisoma was on 1 January 2006 by the unification of the city Haramachi ( 原町市 , -shi ) with the small towns of Kashima ( 鹿島町 , - machi ) and Odaka ( 小高町 , -machi ) of the district Sōma founded. These former parishes now form urban districts within Minamisōma, the name of which comes from the district and means "South Sōma".

Tōhoku earthquake, tsunam and nuclear disaster in 2011

Damage and sacrifice

On March 11, 2011, the Tōhoku earthquake and the tsunami it triggered completely destroyed over 2,300 residential buildings. and 2,430 others partially.

The Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA) reported 631 dead and 7 missing persons for Minamisōma as a result of the Tōhoku triple disaster of 2011 up to their 145th damage report of March 13, 2012, then increased their number in their 146. Damage report from September 28, 2012 on 852 dead and 111 missing and up to the 158th damage report from September 7, 2018 on 1038 dead and 111 missing.

Measured against the total population of Minamisōma, which was given as 70,878 in the 2010 census, the victim rate from the 2011 disaster was 1.6% if all dead and missing persons registered in the 157th FDMA damage report of March 7, 2018 or 0.90% if the victims registered in the 153rd FDMA damage report of March 8, 2016 (1,015 dead and 111 missing) minus the catastrophe-related deaths reported by the Reconstruction Agency (RA) are taken into account, resulting in a 637 dead and missing results. With the same database, but based solely on the floodplain area of the tsunami in Minamisōma, which covered an area of 39 km 2 , the casualty rate was 4.76%.

The tsunami has been identified as the cause of the deaths of 636 people in Minamisōma, 39.7% of the total of 1,604 tsunami deaths in Fukushima Prefecture. As of July 2012, 388 deaths had been classified in the disaster-related deaths category officially defined by the Reconstruction Agency for cases where death was the result of indirect damage caused by earthquakes or tsunami and nuclear disaster. The majority of these catastrophe-related deaths are attributed to the evacuation of older people after the nuclear accident.

According to media reports, only a single pine tree survived the tsunami from tens of thousands of trees in a coastal protection forest in the Kashima area of Minamisōma, which stood about 100 m inland from the coast in the Minamimigita area of Kashima, where 54 people were killed by the tsunami. The surviving pine tree became after the disaster under the name Kashima no Ipponmatsu (か し ま の 一 本 松) a symbol of mourning for the victims and for the rebuilding of the area after the disaster. Since the pine was weakened by salt damage, it was felled on December 27, 2017 while celebrations were held.

Field studies in the Minamisōma restricted area were only possible with a delay of 15 months after the Tōhoku tsunami of 2011 because the area (in the southern coastal areas of Minamisōma until June 2012) was due to the high radiation exposure caused by the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant , Was the subject of restricted access. The increased tsunami heights in the coastal areas can be attributed to the reflection of ocean waves, funnel formation, splash-up effects on rocks and dykes / breakwaters as well as to the increased flow resistance that the tsunami had when passing through the pine forests on the coastline. Therefore, tsunami heights of 10 m were limited to the areas up to 500 m from the coast. On land, the maximum flood levels were dependent on the topography . While the inland tsunami heights continued to rise in the steeply rising V-shaped valleys, they fell as the flooding distance increased along the flat coastal plains. The flood level was higher behind completely destroyed dykes than behind partially damaged coastal protection systems. In the Obama area, for example, the coastal dikes were 32% destroyed (469 m by 1,483 m), while in Tsukabara they were 5% (99 m by 2,041 m), in Tsunobeuchi 4% (61 m by 1,581 m) and in Murakami and Idagawa were 0% destroyed. Compared to the Sendai Plain, the tsunami heights on the Fukushima coast were increased due to the convex coastline and the associated bathymetry off the coast, which tends to concentrate the tsunami energy.

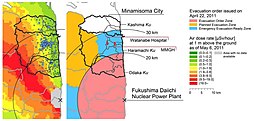

and the long-term evacuation zones

Orange = restricted area within a 20 km radius

Yellow = "Evacuation Prepared Area"

Pink = "Deliberate Evacuation Area"

In addition to the restricted area and “Deliberate Evacuation Area”, there are 3 categories:

Category 1: Area ready for the evacuation order to be lifted

Category 2 = residents are prohibited from permanent residence.

Category 3 = long-term unsuitable for return of residents

reference to nuclear accident and evacuation zones

reference to nuclear accident and evacuation zones

Right : evacuation zones prescribed on April 22, 2011 according to the air dose rates:

red : Evacuation Order Zone

orange : Planned Evacuation Zone

blue : Emergency Evacuation-Ready Zone

MMGH = Minamisōma Municipal General Hospital.

dark blue : areas affected by the tsunami

evacuation zones 2014:

yellow : no return of the residents expected for a long time

red : residents are not allowed to stay permanently

green : ready to lift the evacuation order

Evacuation in Fukushima Prefecture

The city of Minamisōma is 14 to 38 km north of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant as the starting point of the nuclear disaster .

On 12 March 2011, the Japanese central government in response and countermeasure explained to the nuclear disaster at Fukushima nuclear emergency and ordered the evacuation of all areas within a radius of 20 km of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (also English. Restricted area / dt. "Sperrgebiet" or English mandatory evacuation zone / dt. "obligatory evacuation zone ") or with a high radiation dose. However, there were also many other locations with high radiation values beyond this 20 km radius, as radioactive particles were carried away from the damaged power plant by the wind. These places included Minamisōma and 10 other villages and cities, including Naraha , Tomioka , Kawauchi , Ōkuma , Futaba , Namie , Katsurao , Iitate , Tamura and Kawamata .

On March 15, 2011, the residents who lived at a distance of 20-30 km from the damaged nuclear power plant ( Evacuation Prepared Area ) were instructed to remain in their houses for their protection ( indoor sheltering zone ).

After the evacuation orders were issued on May 7, 2013, these regions were divided into four different categories according to their radioactive exposure: Areas with a radiation exposure of less than 20 mSv per year, which were treated by the government as a threshold value for permanent return Category 1. Areas of this Category 1 could be entered at their own discretion and without the use of protective equipment with the only restriction that they were not allowed to stay overnight there. These areas were ready for the evacuation order to be lifted. In areas with a radiation exposure between 20 and 50 mSv per year (category 2), residents were prohibited from permanent residence. Areas with over 50 mSv per year (category 3) were seen as unsuitable for a return of residents in the long term. A fourth evacuation area had a special status.

The establishment of the mandatory evacuation zone in Fukushima Prefecture resulted in the evacuation of over 80,000 people in that zone, of whom over 70,000 were still evacuated as of September 5, 2015. The Sōsō region in the northeast of Fukushima Prefecture on the coast, where the nuclear power plant was also located, was hit by all three disasters (earthquake, tsunami and nuclear accident) and was one of the regions of Japan most severely affected by the triple disaster.

Evacuation in Minamisōma

In Minamisōma, the largest community in the Sōsō region, there was a significant loss of population, with the original population dropping dramatically from almost 72,000 people before the disaster to around 10,000 in April 2011 within a month. As of February 27, 2014, of the 71,561 inhabitants of the city before the disaster, 7,276 had moved, 14,430 were still registered but lived outside of the city and 46,868 were living in the city. By October 2015, the population slowly recovered to 57,000. According to other sources, the population of the city of Minamisōma was 66,800 a year after the nuclear accident in March 2012. As of August 2016, 2,412 residents of Minamisōma were still living in temporary accommodation.

The city of Minamisōma had areas that belonged to the exclusion zone (20 km away from the nuclear power plant) (originally with around 10,955 inhabitants, i.e. 16% of the total population of the city), as well as areas that belonged to the indoor sheltering zone (20-30 km distance from the nuclear power plant) belonged (originally with around 44,773 inhabitants, i.e. 66% of the total population of the city). Minamisōma is considered a unique city in terms of evacuation, where residents have undergone a series of evacuation orders and countermeasures, and likely faced nuclear radiation fears after the disaster. The city of Minamisōma can be seen as a uniquely suitable case for evaluating how mass evacuation can affect the demographics of the remaining residents.

Even outside the exclusion zone, there was massive voluntary evacuation from Minamisōma, with almost 90% of the residents both from the zone in which people were supposed to stay in their homes ("indoor sheltering zone", 20-30 km from the damaged nuclear power plant), as well as voluntarily evacuated from the rest of the city. The decline in the total population of the city of Minamisōma reached its lowest point on March 22, 2011 (11 days after the disaster), when the population of 7,107 people had shrunk to 11% compared to the time before the disaster (67,044 inhabitants). At this point in time, 132 (1.1% of the original residents) remained in the exclusion zone, 5,595 (12.5%) in the indoor sheltering zone and 1,333 (12.6%) in other areas of the city. .

The city of Minamisōma was also the first community to initiate an internal screening program for radioactive contamination of residents in response to the Fukushima nuclear disaster . In July 2011, the city made the internal screening program available to its residents free of charge for the voluntary measurement of radiation exposure via the installation of full-body counters in the Minamisōma Municipal General Hospital (MMGH, Japanese南 相 馬 市立 総 合 病院) 23 km north of the nuclear power plant, initially with two armchairs Devices of Japanese production (one from July 2011, another from August 2011), which in September 2011 for better shielding against background ɣ radiation by a device type for measurements while standing, American production (FASTSCAN, Model 2251, Canberra Inc.) have been replaced. From July 2012, another armchair-like full-body counter of Japanese production was made available, which was set up in the Watanabe Hospital, which is about 3 km from the MMGH. The city also carried out a questionnaire using this screening in order to obtain detailed data on evacuation behavior such as the location and duration of the evacuation. Between July 11, 2011 and the end of April 2013, 20,149 test persons took part in the full-body counter screening at the MMGH and answered the questionnaire survey on evacuation behavior after the disaster. On the grounds that the whole-body counter devices were not suitable for measuring young children, no preschool children under the age of 6 were admitted to the program. According to the population register, the population of the city of Minamisōma on March 1, 2011 was 70,919 people, of whom 67,929 (96%) were 6 years or older. Of this population, 12,201 people had lived within a 20 km radius of the nuclear power plant (exclusion zone) before the disaster. 44,773 at a distance of 20-30 km from the nuclear power plant ( indoor sheltering zone ) and 10,955 in other areas of the city.

Since mainly young people and middle-aged people evacuated, there was a rapid statistical aging of the population, with the proportion of older residents (≥65 years) increasing from 26.5% in 2010 to 32.0% in 2015. At the same time, the average number of people per household fell from 3.00 in 2010 to 2.23 in 2015. Scientific studies indicate that patterns of voluntary evacuation behavior after the nuclear disaster differed according to gender, age group and household composition. The demographic factors that could be observed when staying in the city of Minamisōma were belonging to the male gender, belonging to the age group between 40 and 64 years, living together with an elderly person and living alone without other household members. In contrast, the demographic factors that were more likely to be observed in the case of voluntary evacuation from the city were belonging to the female gender, belonging to the age group under 20 years and living with children. The results of scientific evaluations in Minamisōma on evacuation behavior agreed with a systematic review according to which women are more likely to be evacuated than men due to gender-specific differences in social roles, evacuation incentives, risk exposure and perceived risk. In particular, residents who live with elderly people or alone in the protection zone and in other areas of the city did not take part in the evacuation.

- Exclusion zone

The Odaka district and the southern part of Haramachi, a total of 107 km², were within the 20 km exclusion zone and have been completely evacuated. With the exception of a few workers in the nuclear power plant, all people initially left the Minamisōma area. Scientific research suggests, however, that a remarkable number of residents remained in the mandatory evacuation zone even after the mandatory evacuation order. In this zone, an estimated 99% (12,524 out of 12,694) of residents were evacuated within ten days of the nuclear disaster. This finding is comparable to the situation after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1987, when some residents known as Samosely lived voluntarily in the exclusion zone around the damaged Chernobyl nuclear power plant and were therefore probably cut off from public support such as health insurance or pensions . On April 16, 2012, some parts that had previously been completely closed, such as Odaka, could be re-entered, but not inhabited.

- "Evacuation Prepared Area" and "Deliberate Evacuation Area"

The part of Haramachi not belonging to the exclusion zone and the southern part of Kashima, a total of 181 km², were in the 30 km wide zone in which evacuation was recommended, while only the remaining 111 km² were considered harmless. In the 20-30 km zone, the population decreased rapidly after an order was published on March 15, 2011 that the population should seek shelter in their homes. Even some transport companies no longer let their employees into the area after this order, which increased bottlenecks in the supply of resources such as food and medicines. On April 16, 2012, parts of the evacuation zone were lifted.

On May 31, 2016, those evacuation zones in Minamisōma where voluntary evacuation was recommended were lifted. The evacuation zone remained, in which evacuation was compulsory.

On March 31 and April 1, 2017, the Japanese government revoked the evacuation orders for around 32,000 residents from the four radiation-contaminated communities of Iitate, Kawamata, Namie and Tomioka, allowing them to return to their homes. The only places that were still the subject of evacuation orders were Futaba and Ōkuma and parts of the five neighboring towns and villages Minamisōma, Iitate, Namie, Tomioka and Katsurao.

Reconstruction and returnees

The mayor, Katsunobu Sakurai, attracted a lot of international media attention when he publicly criticized the Japanese government over the Internet for abandoning the city over the nuclear disaster. In an 11-minute video posted on YouTube , Sakurai sought outside help, saying the city received little information from the government and Tepco and had been isolated. The call for help sparked reactions around the world, with Time magazine listing Sakurai in its April 2011 list of the One Hundred Most Influential People as a Reconstruction Icon. Almost nine months later, according to media reports, Sakurai itself was increasingly criticized by local residents, saying that the problem was no longer the government, but was with the civil service officials who refused to help his city.

Despite extensive government support and an enormous amount of resources allocated to the disaster area, the reconstruction of Minamisōma continued to be slow two years after the disaster. No major progress has been made in reconstruction in terms of population return, the decontamination process, and economic recovery. In addition to the complicated situation in the disaster area, the inadequate participation of stakeholders in decision-making processes was also seen by many experts as a factor hindering the reconstruction process. For example, the decontamination group encountered strong resistance from landowners when attempting to decontaminate the mostly privately owned contaminated land in Minamisōma. Some landowners refused to accept the government-designated nuclear waste dumps as such and expressed doubts about the effectiveness of the decontamination methods.

Attractions

The region, d. H. Minamisōma, Sōma and the district of Futaba , is known for the Sōma Nomaoi ( 相 馬 野馬 追 ). This tradition, which has been recognized as an important national cultural asset , is an annual horse race at the end of July with riders in full samurai armor, which goes back to the fiefdom ( Han ) Sōma or its ruling Sōma clan.

In Minamisōma is the listed Sakurai- Kofun ( 桜 井 古墳 ), a barrow with 74.5 m in circumference and 6.8 m in height from the 4th or 5th century. Another listed work is the Daihi-san no Sekibutsu ( 大悲 山 の 石 仏 ), a group of several stone Buddhas that were carved into the rock in one piece. The also listed Urajiri-kaizuka ( 浦 尻 貝 ) is a Køkkenmøddinger with settlement remains from the prehistoric Jōmon period .

The Amida-ji temple from 1406 stands in the Kashima district .

In the north there is the Haramachi incineration power plant ( 原 町 火力 発 電 所 , Haramachi karyoku hatsudensho ) with breakwaters that protrude more than 1.5 km into the sea. Because of the waves it created, the immediate area was a popular surfing beach.

traffic

The most important highway is the Jōban highway to Misato in Saitama Prefecture or Watari in Miyagi Prefecture . Other important ones are the national road 6 to Chūō in Tokyo or Sendai, as well as the national road 114 to the prefecture capital Fukushima or to the neighboring Namie.

Minamisōma is connected to the national rail network via the JR Jōban line , which is also served by the Super Hitachi express train , to Sendai or Ueno . The stops in the city are Momouchi, Odaka, Iwaki-Ōta, Haranomachi and Kashima, with Haranomachi being the main train station.

education

Minamisōma has 16 elementary schools, 6 middle schools and 4 state high schools run by the prefecture, which differ in their specializations:

- the Haramachi High School ( 福島 県 立 原 町 高等学校 , Fukushima-kenritsu Haramachi kōtō gakkō ),

- the Minamisōma Agricultural High School ( 相 馬 農業 高等学校 , Fukushima-kenritsu Minamisōma nōgyō kōtō gakkō ),

- the Odaka Technical High School ( 福島 県 立 小 高 工業 高等学校 , Fukushima-kenritsu Odaka kōgyō kōtō gakkō ) and

- the Odaka Commercial High School ( 福島 県 立 小 高 商業 高等学校 , Fukushima-kenritsu Odaka shōgyō kōtō gakkō ).

There is also the private Shōei high school ( 松 栄 高等学校 , Shōei kōtō gakkō ).

In the course of the evacuation of Odaka, both high schools, the Odaka middle school and the four primary schools were relocated to other parts of the city.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Shinji Sato, Akio Okayasu, Harry Yeh, Hermann M. Fritz, Yoshimitsu Tajima, Takenori Shimozono: Delayed Survey of the 2011 Tohoku Tsunami in the Former Exclusion Zone in Minami-Soma, Fukushima Prefecture . In: Pure and Applied Geophysics . tape 171 , no. December 12 , 2014, p. 3229-3240 , doi : 10.1007 / s00024-014-0809-8 . (Published online March 29, 2014).

- ↑ a b In Japan, tree that survived 2011 tsunami cut down ( memento July 23, 2018 on WebCite ) , standard.net, December 27, 2017 (The Japan News / Yomiuri).

- ↑ 【原 町 の 介 護 老人 保健 施 設 ヨ ッ シ ー ラ ン ド 1】 津 波 到来 想 定 な し 警報 届 か ず 犠 牲 に ( Memento from July 23, 2018 on WebCite ) , minpo.jp, March 6, 2012.

-

↑ a b c 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (第 158 報) ( Memento from October 3, 2018 on WebCite )

ホ ー ム> 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) 被害 報> 【過去】 被害 報> 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 被害 報 157 報 ~ (1 月 ~ 12 月) ( Memento from October 3, 2018 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 158. Damage report, September 7, 2018. - ↑ Century quake in Japan: More than 10,000 people are missing. In: Zeit Online. March 12, 2011, accessed March 21, 2011 .

- ^ Survivors in trauma after life-changing nightmare day. In: The Japan Times Online. March 13, 2011, accessed March 21, 2011 .

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 145 報) ( Memento from April 12, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento from April 12, 2018 on WebCite )), 総 務 省 消防庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 145th report, March 13, 2012.

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (第 124 報) ( Memento from March 25, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento from March 25, 2018 on WebCite )), 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 124th report, May 19, 2011.

- ↑ 東 日本 大 震災 図 説 集 . In: mainichi.jp. Mainichi Shimbun- sha, May 20, 2011, archived from the original on June 19, 2011 ; Retrieved June 19, 2011 (Japanese, overview of reported dead, missing and evacuated).

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 146 報) ( Memento from April 12, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento from April 12, 2018 on WebCite )), 総 務 省 消防庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 146th report, September 28, 2012.

- ↑ 平 成 22 年 国 勢 調査 - 人口 等 基本 集 計 結果 - (岩手 県 , 宮城 県 及 び 福島 県) ( Memento from March 24, 2018 on WebCite ) (PDF, Japanese), stat.go.jp (Statistics Japan - Statistics Bureau , Ministry of Internal Affairs and communication), 2010 Census, Summary of Results for Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima Prefectures, URL: http://www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2010/index.html .

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 157 報) ( Memento of March 18, 2018 on WebCite ) ( PDF ( Memento of March 18, 2018 on WebCite )), 総 務 省 消防庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), March 7, 2018.

- ↑ Tadashi Nakasu, Yuichi Ono, Wiraporn Pothisiri: Why did Rikuzentakata have a high death toll in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster? Finding the devastating disaster's root causes . In: International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction . tape 27 , 2018, p. 21-36 , doi : 10.1016 / j.ijdrr.2017.08.001 . (Published online on August 15, 2017), here p. 22, table 2.

- ↑ 平 成 23 年 (2011 年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 (東 日本 大 震災) に つ い て (第 153 報) ( Memento of March 10, 2016 on WebCite ) , 総 務 省 消防 庁 (Fire and Disaster Management Agency), 153rd report, March 8, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d Haruka Toda, Shuhei Nomura, Stuart Gilmour, Masaharu Tsubokura, Tomoyoshi Oikawa, Kiwon Lee, Grace Y. Kiyabu, Kenji Shibuya: Assessment of medium-term cardiovascular disease risk after Japan's 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident: a retrospective analysis . In: BMJ Open . tape 7 , no. December 12 , 2017, p. 1–9 , doi : 10.1136 / bmjopen-2017-018502 . (Published online December 22, 2017); License: Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0).

- ↑ cf. Akihiko Ozaki, Shuhei Nomura, Claire Leppold, Masaharu Tsubokura, Tetsuya Tanimoto, Takeru Yokota, Shigehira Saji, Toyoaki Sawano, Manabu Tsukada, Tomohiro Morita, Sae Ochi, Shigeaki Kato, Masahiro Kami, Tsuyoshi Kaniazoto, Yukomio cancer patient delay in Fukushima, Japan following the 2011 triple disaster: a long-term retrospective study . In: BMC Cancer . tape 17 , no. 423 , 2017, ISSN 1471-2407 , p. 1-13 , doi : 10.1186 / s12885-017-3412-4 . (Published online June 19, 2017); License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 2, Fig. 1.

- ↑ a b Reiko Hasegawa: Disaster Evacuation from Japan's 2011 Tsunami Disaster and the Fukushima Nuclear Accident . In: Studies . No. 5 , 2013, ISSN 2258-7535 , p. 1-54 . (Institut du développement durable et des relations internationales, IDDRI).

- ↑ Masaru Arakida, Mikio Ishiwatari: Evacuation . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , Chapter 11, pp. 99-108 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Mikio Ishiwatari, Satoru Mimura, Hideki Ishii, Kenji Ohse, Akira Takagi: The Recovery Process in Fukushima . In: Federica Ranghieri, Mikio Ishiwatari (Ed.): Learning from Megadisasters - Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake . World Bank Publications, Washington, DC 2014, ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2 , chap. 36 , p. 331–343 , doi : 10.1596 / 978-1-4648-0153-2 ( work accessible online on Google Books [accessed April 3, 2018]). , here: p. 335, Map 36.1 "Rearrangement of evacuation zoning" "Source: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.", License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Evacuation Areas Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), (METI Measures and Requests in response to the Great East Japan Earthquake> Assistance of Residents Affected by the Nuclear Incidents> Evacuation Areas): Restricted areas and areas to which evacuation orders have been issued (June 15, 2012) ( Memento July 9, 2018 on WebCite ) (PDF)

- ↑ Akihiko Ozaki, Shuhei Nomura, Claire Leppold, Masaharu Tsubokura, Tetsuya Tanimoto, Takeru Yokota, Shigehira Saji, Toyoaki Sawano, Manabu Tsukada, Tomohiro Morita, Sae Ochi, Shigeaki Kato, Masahiro Kami, Tsuyoshi Nemoto, Yukio Kanazawa, Hiromichi Ohira: Breast cancer patient delay in Fukushima, Japan following the 2011 triple disaster: a long-term retrospective study . In: BMC Cancer . tape 17 , no. 423 , 2017, ISSN 1471-2407 , p. 1-13 , doi : 10.1186 / s12885-017-3412-4 . (Published online June 19, 2017); License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 3, Fig. 1.

- ↑ Claire Leppold, Shuhei Nomura, Toyoaki Sawano, Akihiko Ozaki, Masaharu Tsubokura, Sarah Hill, Yukio Kanazawa, Hiroshi Anbe: Birth Outcomes after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Disaster: A Long-Term Retrospective Study . In: International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . tape 14 , no. 5 , 2017, p. 542 ff. (14 pp.) , doi : 10.3390 / ijerph14050542 . (Published online May 19, 2017); License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 3, Figure 1. "Map of Minamisoma Municipal General Hospital (MMGH) in relation to Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant and evacuation zones."

- ↑ Tomohiro Morita, Shuhei Nomura, Tomoyuki Furutani, Claire Leppold, Masaharu Tsubokura, Akihiko Ozaki, Sae Ochi, Masahiro Kami, Shigeaki Kato, Tomoyoshi Oikawa: Demographic transition and factors associated with remaining in place after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster and related evacuation orders . In: PLoS ONE . tape 13 , no. 3 , 2018, p. e0194134 , doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0194134-1-e0194134-17 . (Published online March 14, 2018). License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. E0194134-3, Fig. 1. "Location of Minamisoma City".

- ↑ Shuhei Nomura, Masaharu Tsubokura, Akihiko Ozaki, Michio Murakami, Susan Hodgson, Marta Blangiardo, Yoshitaka Nishikawa, Tomohiro Morita, Tomoyoshi Oikawa: Towards a Long-Term Strategy for Voluntary-Based Internal Radiation Contamination Monitoring: A Population-Level Analysis of Monitoring Prevalence and Factors Associated with Monitoring Participation Behavior in Fukushima, Japan . In: International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . tape 14 , no. 4 , 2017, p. pii: E397 (18 pages) , doi : 10.3390 / ijerph14040397 . (Published April 9, 2017). License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 4/18, Fig. 1 ("Locations of Minamisoma City and two whole body counter-installed hospitals").

- ↑ Hui Zhang, Zijun Mao, Wei Zhang: Design Charrette as Methodology for Post-Disaster Participatory Reconstruction: Observations from a Case Study in Fukushima, Japan . In: Sustainability . tape 7 , no. 6 , 2015, p. 6593-6609 , doi : 10.3390 / su7066593 . (Published online May 26, 2015). License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 6598, Figure 1 "The map of the study area: Minamisoma City"

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Tomohiro Morita, Shuhei Nomura, Tomoyuki Furutani, Claire Leppold, Masaharu Tsubokura, Akihiko Ozaki, Sae Ochi, Masahiro Kami, Shigeaki Kato, Tomoyoshi Oikawa: Demographic transition and factors associated with remaining in place after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster and related evacuation orders . In: PLoS ONE . tape 13 , no. 3 , 2018, p. e0194134 , doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0194134-1-e0194134-17 . (Published online March 14, 2018). License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

- ↑ a b c 南 相 馬 市 の 状況 に つ い て (概要) . (No longer available online.) Minamisōma, April 6, 2011, archived from the original on August 20, 2012 ; Retrieved August 10, 2016 (Japanese). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Dinil Pushpalal, Zhang Yan, Tran Thi Diem Thi, Yuri Scherbak, Michiko Kohama: Tears of Namie: An Appraisal of Human Security in the Township of Namie . In: Dinil Pushpalal, Jakob Rhyner, Vilma Hossini (eds.): The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake 11 March 2011: Lessons Learned And Research Questions - Conference Proceedings (11 March 2013, UN Campus, Bonn) . 2013, ISBN 978-3-944535-20-3 , ISSN 2075-0498 , pp. 80-87 .

- ↑ a b c d e Akihiko Ozaki, Shuhei Nomura, Claire Leppold, Masaharu Tsubokura, Tetsuya Tanimoto, Takeru Yokota, Shigehira Saji, Toyoaki Sawano, Manabu Tsukada, Tomohiro Morita, Sae Ochi, Shigeaki Kato, Masahiro Kami, Tsuy .oshi Noshi , Hiromichi Ohira: Breast cancer patient delay in Fukushima, Japan following the 2011 triple disaster: a long-term retrospective study . In: BMC Cancer . tape 17 , no. 423 , 2017, ISSN 1471-2407 , p. 1-13 , doi : 10.1186 / s12885-017-3412-4 . (Published online June 19, 2017); License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

- ↑ Hisanori Fukunaga, Hiromi Kumakawa: Mental Health Crisis in Northeast Fukushima after the 2011 Earthquake, Tsunami and Nuclear Disaster . In: The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine . tape 237 , no. 1 , 2015, p. 41-43 , doi : 10.1620 / tjem.237.41 .

- ↑ 避難 の 状況 と 市内 居住 の 状況 . (No longer available online.) Minamisōma, archived from the original on March 11, 2014 ; Retrieved February 27, 2014 (Japanese). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b Shuhei Nomura, Masaharu Tsubokura, Akihiko Ozaki, Michio Murakami, Susan Hodgson, Marta Blangiardo, Yoshitaka Nishikawa, Tomohiro Morita, Tomoyoshi Oikawa: Towards a Long-Term Strategy for Voluntary-Based Internal Radiation Contamination Monitoring: A Population-Level Analysis of Monitoring Prevalence and Factors Associated with Monitoring Participation Behavior in Fukushima, Japan . In: International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . tape 14 , no. 4 , 2017, p. pii: E397 (18 pages) , doi : 10.3390 / ijerph14040397 . (Published April 9, 2017). License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

- ↑ COUNTDOWN TO DEC. 16: Deserted Minami-Soma remains a city without hope. In: Asahi Shimbun. December 11, 2012, archived from the original on March 4, 2016 ; accessed on August 10, 2016 .

- ^ Evacuation order lifted for parts of Minamisoma. In: Kyodo. April 17, 2012, accessed February 27, 2014 .

- ↑ Even as Evacuation Orders are Lifted, Recovery Remains Distant Prospect for Many Fukushima Residents ( Memento July 14, 2018 on WebCite ) , nippon.com, May 24, 2017, by Suzuki Hiroshi.

- ↑ Areas to which evacuation orders have been issued (Apr 1, 2017) ( Memento from July 17, 2018 on WebCite ) , meti.go.jp (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, METI).

- ↑ Hui Zhang, Zijun Mao, Wei Zhang: Design Charrette as Methodology for Post-Disaster Participatory Reconstruction: Observations from a Case Study in Fukushima, Japan . In: Sustainability . tape 7 , no. 6 , 2015, p. 6593-6609 , doi : 10.3390 / su7066593 . (Published online May 26, 2015). License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Here: p. 6599, Figure 2 "Triple disaster struck area in Minamisoma City. (Source: Above photos were taken by Hui Zhang on March 12, 2014.)"

- ↑ a b c Near Fukushima, Japan, famed mayor loses residents' support - Residents turn against Mayor Katsunobu Sakurai after he urges them to help with the nuclear cleanup in Minamisoma, Japan, a town just 15 miles from the stricken Fukushima plant ( page 1 ( Memento dated July 23, 2018 on WebCite ), page 2 ( Memento dated July 23, 2018 on WebCite )), articles.latimes.com (Los Angeles Times), December 1, 2011, by John M. Glionna.

- ↑ TIME 100 Most Influential People: See Which World Figures Made The 2011 List ( Memento from July 23, 2018 on WebCite ) , huffingtonpost.com, April 22, 2011 (June 22, 2011 update).

- ↑ Hui Zhang, Zijun Mao, Wei Zhang: Design Charrette as Methodology for Post-Disaster Participatory Reconstruction: Observations from a Case Study in Fukushima, Japan . In: Sustainability . tape 7 , no. 6 , 2015, p. 6593-6609 , doi : 10.3390 / su7066593 . (Published online May 26, 2015). License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

- ↑ 学校 一 覧 . Minamisōma, accessed February 27, 2014 (Japanese).

Remarks

- ↑ In Japan there is a nationwide resident registration network , the Basic Resident Register (Japanese 住民 基本 台帳 ネ ッ ト ワ ー ク シ ス テ ム), which is administered by each municipality unit (city, town, village) and contains basic data of the registered residents such as name, gender, date of birth and address . Because many evacuees did not change their address entry in the Basic Resident Register of their community of origin after the nuclear accident, the registered address after the nuclear accident did not necessarily include the actual address. However, evacuees reported their evacuation or resettlement status, which includes residential address, to the Minamisōma City Office in order to receive important city notices such as tax payments, disaster recovery insurance, and compensation claims. In 2015, the city of Minamisōma created an "evacuation database" by combining these evacuation records for each person with the corresponding data from the Basic Resident Register . (Source: Shuhei Nomura, Masaharu Tsubokura, Akihiko Ozaki, Michio Murakami, Susan Hodgson, Marta Blangiardo, Yoshitaka Nishikawa, Tomohiro Morita, Tomoyoshi Oikawa: Towards a Long-Term Strategy for Voluntary-Based Internal Radiation Contamination Monitoring: A Population-Level Analysis of Monitoring Prevalence and Factors Associated with Monitoring Participation Behavior in Fukushima, Japan . In: International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . Volume 14 , no. 4 , 2017, p. pii: E397 (18 pages) , doi : 10.3390 / ijerph14040397 . )

Web links

- 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図 , 国土 地理 院 ( Kokudo Chiriin , Geospatial Information Authority of Japan, formerly: Geographical Survey Institute = GSI), www.gsi.go.jp: 地理 院 ホ ー ム> 防災 関 連> 平 成 23 年 (2011年) 東北 地方 太平洋 沖 地震 に 関 す る 情報 提供> 10 万分 1 浸水 範 囲 概況 図:

- The GSI published here two maps with Minamisoma ( 浸水範囲概況図14 , 浸水範囲概況図15 ) on which the 2011 flooded the Tōhoku tsunami areas are drawn on the basis of reports of aerial photographs and satellite imagery, as far as was possible.

- Sōma Nomaoi website (English, Japanese)