Negative voice weight

Negative weighting of votes (also inverse success value ) describes an effect in elections in which the votes cast against the will of the voters ; So either votes for a party , which mean a loss of parliamentary mandates for it, or votes that are not cast for a party and this brings more seats. It contradicts the principle of equality of choice , according to which every vote should count equally, and violates the claim that the vote must not work explicitly against the will of the electorate.

In Germany , according to a ruling by the Federal Constitutional Court on July 3, 2008 , the effect of negative voting weight cannot be reconciled with the constitutional principles of equality and directness of election .

Significance for elections to the German Bundestag

In the federal elections up to and including 2009 it was first determined how many mandates a party is entitled to nationwide according to the second vote distribution. In the second step, these mandates are distributed to the federal states depending on the second vote results in the individual federal states . Finally, it is checked individually in each country how many mandates the party has already received there through direct mandates (in constituencies ). The other mandates to which the party is entitled in this federal state are allocated to the party on the basis of the respective state list .

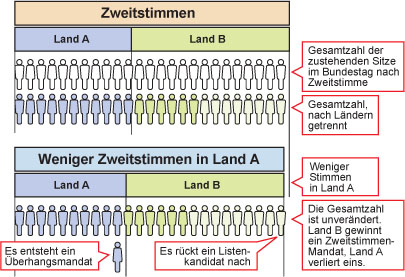

This can lead to the phenomenon of overhang mandates: If a party in a federal state has received more direct mandates than it is entitled to according to the second vote, it still retains all direct mandates. The number of mandates to which she is entitled after the second vote result is called overhang mandate . Any compensatory seats for the other parties did not exist before.

The following scenario can result in a negative voting weight: Assuming a party in federal state A receives an overhang mandate. If she were to win additional second votes in this federal state, this could mean that the total number of seats to which she was entitled after the second vote result would remain unchanged, but the distribution between the federal states would change. The additional second votes can result in the party receiving one more mandate in federal state A, but one less mandate in another federal state B, after the second vote result. However, with the mandate gained in country A, the overhang mandate would cease to exist, so that the party from country A would not be able to send an additional member of the Bundestag. In federal state B, however, she would get one less mandate, provided she does not receive any overhang mandates there. The party would have lost one mandate overall, despite more second votes.

Federal Constitutional Court judgment 2008

The legislature did not make any major efforts to remedy this phenomenon. Following a corresponding lawsuit, the Federal Constitutional Court, in its judgment of July 3, 2008, declared the existing federal election law to be unconstitutional due to the possibility of negative voting weight. It violates the principles of equality and immediacy of choice :

“An electoral system that is designed, or at least in typical constellations, that an increase in votes leads to the loss of mandates or that more mandates are obtained for the election proposal of a party if it has fewer votes or a competing proposal has more votes , leads to arbitrary results and makes the democratic competition for approval by eligible voters seem absurd. "

The legislature was commissioned to amend the electoral law by June 30, 2011 so that this effect is no longer possible in the future and the principles of electoral law are no longer violated. On September 30, 2011, well after the deadline set by the Federal Constitutional Court had expired, the Bundestag then passed an electoral reform with the votes of the CDU , CSU and FDP , which was intended to largely eliminate the negative voting weight in elections.

Since the SPD and the Greens felt that the new regulation did not achieve this goal , the opposition filed a constitutional complaint . The association Mehr Demokratie also announced a lawsuit against the reform of the electoral law and called on interested parties to participate. By December 12, 2011, almost 3,000 complaints collected in this way had been submitted to the Federal Constitutional Court. The complainants were of the opinion that the effect of the negative voting weight could occur in a constitutionally unacceptable manner even under the amended federal electoral law.

Federal Constitutional Court judgment 2012

On June 5, 2012, the Federal Constitutional Court negotiated the constitutional complaint orally, together with the organ dispute proceedings and the judicial review proceedings. On July 25, 2012, the court confirmed the plaintiffs' concerns and declared the new regulation resolved by the Union and FDP to be unconstitutional. The Federal Electoral Act, amended in 2011, also violates "the principles of equality and immediacy of the election as well as equal opportunities for the parties [...] because it enables the effect of negative voting weight." Equality of electoral rights and equal opportunities for the parties is also violated by unpaid overhang mandates, which "cancels the basic character of the federal election as proportional representation."

Occurrence in the current federal election law

The new regulations on the allocation of seats that came into force in May 2013 are not free from negative voting weight. This can arise if, in the distribution on the basis of a fixed number of seats per country, one party gains an additional seat through additional votes at the expense of another party and thus the number of equalization mandates is reduced, or vice versa, fewer votes for one party lead to additional equalization mandates would. In 2009, if the current allocation procedure had been applied, 7,000 more votes for the Die Linke party in Hamburg would have resulted in the distribution at state level that this party would have won an additional seat and the CDU would have lost one seat. This elimination of the seat for the CDU would have also led to four elimination of compensation mandates at the federal level. This would have reduced the Bundestag from 671 to 666 seats and Die Linke would only have 84 instead of 85 seats. In the 2013 Bundestag election, 100,000 more votes for the SPD in Bavaria would have resulted in the SPD having only 191 seats in the Bundestag instead of 193 and only 622 seats in the Bundestag instead of 631.

Other occurrences

In referendums , it is possible that negative voting weight occurs if they are subject to a participation quorum . Votes against the proposal can then lead to the quorum being exceeded in the first place and the proposal being accepted. As far as quorums are considered to be sensible in referendums at all, they are now increasingly being implemented via an approval quorum - in order to avoid negative voting weight.

A negative voting weight sometimes also occurs in other voting procedures. Most of the other types of negative voting weights, however, are rarer and have less influence on the award of mandates than the type essential for federal election law. Negative weight of votes is currently outside Germany z. B. possible in parliamentary elections in the Czech Republic and in state elections in most Austrian federal states.

Negative voting weights can arise independently of the seat allocation procedure as well as directly in connection with the Hare and Niemeyer procedure . Systems with balancing mandates, for example , which are awarded in some state elections, are highly susceptible to negative voting weights . Their cause lies mostly in the Hare-Niemeyer-specific Alabama paradox .

Also specific to the Hare-Niemeyer process (or for the deviation from the allocation of seats according to d'Hondt ) is the possibility of the threshold paradox . A party can get fewer seats if it pushes another party under the threshold clause with a larger number of votes . This paradox can occur particularly with a relatively small number of mandates to be awarded.

It also shows up in runoff elections and instant runoff voting .

generalization

The Federal Constitutional Court used the term negative voting weight in 2012 in a more general sense. Accordingly, the negative voting weight is also present if the number of seats of a party correlates, contrary to expectations, with the number of votes allocated to a competing party.

A seat allocation procedure that enables more seats to be obtained for a party’s election proposal if more votes are received for a competing proposal, contradicts the sense and purpose of a democratic election, according to the Federal Constitutional Court. The votes cast work against the will of the voters.

General example

description

In a federal election with 5,980,000 valid votes, a P1 party would receive a total of 250,000 second votes , 106,000 of them in federal state A and 144,000 in federal state B (A and B are the only federal states). In country A the party achieved 11 direct mandates through the first votes , in country B 6, for a total of 17.

Due to the total statutory number of 598 seats in the German Bundestag in accordance with Section 1 BWahlG , there are 25 seats for P1 (598 seats × 250,000 votes ÷ 5,980,000 votes = 25 seats), of which 11 seats (ideal: 10.60) are for country A and 14 seats (14.40) for country B. In country A, all seats due to the party are already occupied by the direct mandates. In country B, the party won only 6 direct seats, the difference of 8 seats is filled by the move up of candidates from country list B. In the end, the party got 25 seats.

Assuming that P1 received 5,000 fewer second votes in country A with otherwise the same number of votes (thus 101,000 second votes and 5,975,000 votes in total), the number of 245,000 second votes also results in a claim of 25 seats in this case (ideal claim: 24 , 52). Calculated separately by country, however, there are only 10 seats (10.11) for country A + 14 seats (14.41) for country B, i.e. a total of 24 seats. The difference of one seat would be offset by an additional 15th seat for country B, filled by a candidate from country list B. In addition, the party in country A would receive an overhang mandate because 11 candidates received a direct mandate regardless of the second vote distribution. In the end, the party gets 11 + 15 = 26 seats.

P1 would therefore be represented with 5,000 second votes fewer with 26 instead of 25 seats in the Bundestag. There is a disproportion of 5.77% of the ratio of the number of votes to the number of mandates: while in the case of the 25 seats 10,000 second votes were required for one seat, in the other case it was only 9,423.1 (disproportion: 1 - (245,000 / 26) / (250,000 / 25) = 5.77%).

(For the sake of simplicity, this example neglects the provision of the federal electoral law that a party that receives an absolute majority of the second votes automatically also receives the majority of the seats.)

Table display

| Mandates based on second votes | Original situation | 5,000 fewer votes in country A. | ||||

| Votes | Ideal claim | State list seats according to Hare-Niemeyer | Votes | Ideal claim | State list seats according to Hare-Niemeyer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country A | 106,000 | 10.60 | 11 | 101,000 | 10.11 | 10 |

| Country B | 144,000 | 14.40 | 14th | 144,000 | 14.41 | 14 + 1 |

| All in all | 250,000 | 25.00 | 25th | 245,000 | 24.52 | 25th |

| Final mandate distribution | State list seats | Direct mandates | Seats result | State list seats | Direct mandates | Seats result |

| Country A | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 (1 ÜM) |

| Country B | 14th | 6th | 14th | 14 + 1 | 6th | 15th |

| All in all | 25th | 17th | 25th | 25th | 17th | 26 (1 ÜM) |

Paradoxically, the party gets one more seat in parliament if 5,000 fewer voters vote for it.

Change options

Since the negative vote weight described can occur independently from the seat allocation process is the change in March 2008 took place in federal election law by the largest remainder method to process according to Sainte-Laguë / Schepers no improvement. Also compensatory seats not solve the problem, because at least one interested party does not receive any compensation mandates regularly.

Negative voting weight can be avoided if internal overhang mandates are prevented. This could be achieved through four different strategies without fundamentally changing the current federal election law:

- Internal overhang mandates could be prevented by offsetting direct and list mandates at the federal level, which would mean that other federal states would issue fewer list mandates. If a constituency winner leaves an overhanging country, a list mandate would revive in the other country. Such models have existed for a long time. In contrast to the currently valid electoral law, majorities based on internal overhang mandates cannot change within an electoral period due to the effect described or even reverse.

- Overhang mandates could be prevented by canceling surplus direct mandates. Such a regulation applied in Bavaria in the state elections from 1954 up to and including 1962: if a party received more direct mandates than it was entitled to based on the proportion of votes, the direct candidates with the lowest number of votes received no seats of the direct candidates with the lowest number of votes, those with the lowest percentage of votes are eliminated.

- With the abolition of state lists and the introduction of federal lists, internal overhang mandates would be excluded.

- As in the 1949 and 1953 Bundestag elections, the seats could be distributed proportionally in the federal states, with each state having a fixed number of seats (without overhang seats). However, this would lead to greater disproportionate effects, especially in favor of parties that are strong where voter turnout is below average; the Left Party would most likely benefit from it. It would be z. For example, it is much more likely than before that one party will get more seats than another party despite fewer votes.

In 1996 the parliamentary group of Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen presented a draft law, which u. a. implements the accounting model described under no. 1 above in order to exclude negative voting weight:

“According to Section 7 (3) of the Federal Election Act, the following paragraph 4 is inserted:

(4) If one or more state lists of a party have overhang seats, the seats that are allotted to the other state lists of this list connection are distributed again. This distribution subtracts the number of constituency mandates that arose in the countries in which overhang mandates arose. The remaining seats are allocated to the state lists, taking into account the electoral district mandates obtained in the other federal states, in accordance with the procedure in accordance with Section 7 (3). If overhang mandates occur again, the process is repeated until there are no more overhang mandates. "

This was intended to neutralize internal overhang mandates and thus prevent negative voting weights. The Bundestag rejected the draft with the votes of the Bundestag factions of the CDU / CSU , SPD and FDP and relied on the reduction of the number of seats to 598 and a new constituency layout. The draft law also provided for the elimination of the possibility of excluding the list connection, so internal overhang mandates would no longer have been possible.

Discussion of legal policy

The phenomenon of negative voting weight was rather neglected in the public discussion. Before the federal election in 2002 , the news magazines Der Spiegel and Focus reported on the issue of negative voting weight.

In the case of biases in success values, there is often a lack of a clear causal assignment of overhang mandates and negative voting weights, as they often work together cumulatively. In 1996, a reform commission of the Bundestag dealt with electoral problems - including overhang mandates - and sought the opinion of experts such as those of Professors Ernst Gottfried Mahrenholz , Wolfgang Löwer and Markus Heintzen . In this context, the Federal Ministry of the Interior developed, among other things, the so-called compensation model I , which provides for a set-off similar to the above-mentioned change option 1 .

Many of the mathematicians and legal scholars involved are sharply critical of the negative voting weight, viewing it as a defect that is incompatible with the requirement of equality, freedom and immediacy (transparency) of an election:

- In their opinion, the equality of the election is violated by the fact that the success value of one vote is lower - namely negative - than the success value if one had not cast a vote.

- Freedom of choice is violated because the voter is no longer free to vote if he can cause harm to the desired party with his vote. This could unsettle a voter and discourage them from voting for their party.

- After all, they do not see the immediacy of the election as given, since due to the defect in the mathematical calculation process that was necessary in between, the votes for a party can no longer be counted in their favor, but in their detriment. The will of the electorate is no longer converted directly into mandates for a party, but rather falsified. A voter is not allowed to vote for his party in order to express his approval.

Negative voting weight can also occur in many proportional representation procedures. However, the uncertainty per party is usually limited to a maximum of one mandate. In addition, most of the other procedures are less vulnerable than that of the federal election system.

Norm review actions

Abstract control of norms 1995/96

In 1995 the government of Lower Saxony had parts of the federal election law reviewed by the Federal Constitutional Court and explicitly put forward the effect of negative voting weights. In their opinion, overhang mandates and negative voting weights produced a distortion of the profit or loss value in cumulative causality, which is so contrary to equality that § 6 and § 7 BWahlG are largely unconstitutional and void. She referred to the jurisprudence of the court and the character of the Bundestag as a unitarian parliament, which is why there were at least three possible changes to meet the equality requirements of Article 38 of the Basic Law . She underlined the above mentioned change option 1 . The result of the hearing of the Federal Returning Officer in this matter supported the critical findings in Lower Saxony's application.

The court confirmed the federal electoral law with the votes of the judges Jentsch , Kirchhof , Kruis and Winter by stalemate. They referred to the legislature's freedom of design and that this could result in system-immanent distortion of profit values. The standards established so far in the case law are, however, not nearly exhaustive, and it is possible to allow other inequalities.

In the opinion of the judges Graßhof , Hassemer , Limbach and Sommer , the electoral system in the scope of the norm control motion is unconstitutional and violates the electoral equality. Certainly, the legislature has a leeway for structuring that it considers necessary, but only within the framework of strict equality of choice: “Necessity alone does not justify entitlement” . You point out that the above bill of Alliance 90 / The Greens completely solves the problems through overhang mandates. Because of the requirement of judicial self-restraint , the court did not have to specify which legislative measures Parliament had to take. However, the legislature must take one of these in order to comply with the constitution.

Judicial review actions in 2011

In response to the 2005 election review complaint, the German Bundestag decided in September 2011 with the votes of the CDU / CSU and FDP to reform the Bundestag electoral law. It was the first time in the history of the Federal Republic that the federal election law was passed solely with the votes of the governing coalition and not with the consensus of all parties. The electoral law reform was discussed extremely controversially in the run-up, because, in the opinion of the opposition and the Federal Constitutional Court, it did not fundamentally eliminate the grievances criticized by the Federal Constitutional Court, but instead continued and unnecessarily complicate the electoral law. Both the SPD , the Greens and Die Linke saw their rights violated and filed a legal action suit .

Election tests because of negative voting weight

Exams by the German Bundestag

With reference to the negative voting weight, the German Bundestag regularly objected to elections, most recently to the Bundestag elections in 1998, 2002 and 2005. The Bundestag always decided - as prepared by the electoral committee - to reject the objections because the provisions of the Federal Electoral Act were observed and the decision on the unconstitutionality of the provisions of the Federal Election Act is left to the Federal Constitutional Court.

Constitutional review of the 1998 Bundestag election

In 2001, the Federal Constitutional Court rejected two election review complaints, including the negative voting weight. However, reasons for this were not given either in these A-Limine decisions or in the letters from the rapporteur.

Constitutional review of the 2002 Bundestag election

An election review complaint regarding the aforementioned objection to the 2002 Bundestag election was pending before the Federal Constitutional Court for an exceptionally long time. In 2004, the then rapporteur for the court, Judge Jentsch , casually described the possible emergence of negative voting weights as still constitutionally acceptable . This view is not supported by curiam in this form. Only after the decision of July 3, 2008 in the electoral review procedure for the following federal election (2005) did the Federal Constitutional Court make a decision with reference to the judgment.

Constitutional review of the 2005 Bundestag election

In the course of the election review of the 2005 Bundestag election, three further complaints were made. The Federal Constitutional Court negotiated two of these proceedings on April 16, 2008. On July 3, 2008, the second Senate announced its verdict: In the opinion of the Karlsruhe judges, the “negative voting weight” is not compatible with the principle of equality and directness of the election. With this, the Federal Constitutional Court declared a regulation of the Federal Election Act to be unconstitutional for the first time in an electoral review process, so that a need for a new legal regulation arose.

Occurrence in federal elections

Election of the German Bundestag until 1998

In the history of the Bundestag elections, the occurrence of negative voting weight in the Bundestag elections in 1990 , 1994 and 2002 has been proven (see web links ). There are also other examples:

- In 1961 the CDU Schleswig-Holstein would have received one more mandate with 39,671 fewer votes. In the same year, the CDU Saarland would have received one more mandate with 48,902 fewer votes.

- In 1983 the SPD Bremen would have received one more mandate with 73,622 fewer votes. Likewise, the SPD Hamburg would have received one more mandate with 73,569 fewer votes.

- In 1987 the CDU Baden-Württemberg would have received one more mandate with 18,705 fewer votes.

- The SPD would have received one more mandate in 1990 if it had received 8,000 fewer votes in Bremen. Likewise, if the CDU had received 2,600 fewer votes in Thuringia , it would have received one more mandate.

- The CDU would have received one more mandate in 1994 if it had received 19,089 votes in Baden-Württemberg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania , Saxony or Saxony-Anhalt or 13,629 fewer in Thuringia.

- The SPD would have received one more mandate in 1998 if it had received 70,955 fewer votes in Brandenburg or 21,323 fewer in Saxony-Anhalt or 21,228 fewer in Thuringia and 1,000 fewer in Brandenburg.

There are also various cases in which a party would have received fewer seats if it had received more votes. This applies to:

- the CDU Schleswig-Holstein 1957 (88,833 votes more, then two seats less),

- the CDU Saarland 1961 (10,828 more, then one less mandate),

- the SPD Schleswig-Holstein in 1980 (7,809 more votes, then one less mandate),

- the SPD Bremen 1983 (4,083 more votes, then one less mandate),

- the SPD Hamburg 1983 (8,199 more votes, then one less mandate),

- the CDU Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania 1990 (13,545 more votes and at the same time 1,000 more votes in Thuringia, then one less mandate),

- the CDU Saxony-Anhalt 1990 (6,314 votes more and at the same time 1,000 votes more in Thuringia, then one less mandate),

- the CDU Thuringia 1990 (66,693 more votes, then one less mandate),

- the SPD Bremen 1994 (1,042 more votes, then one less mandate),

- the SPD Brandenburg 1994 (73,403 more votes, then one less mandate),

- the SPD Hamburg 1998 (16,651 more votes, then one less mandate),

- the SPD Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania 1998 (6,628 votes more, then one less mandate) and

- the SPD Brandenburg 1998 (4,015 more votes, then one less mandate)

Election of the German Bundestag in 2002

In the federal election in 2002 , the SPD lost too many one seat because of 50,000 second votes in Brandenburg that would otherwise have gone to the Bremen SPD state list candidate Cornelia Wiedemeyer .

Calculation of the total number of votes for the 2002 Bundestag election

| Real voting relationships | 50,000 SPD votes less in Brandenburg | |||||

| Votes | Ideal claim | Sit after Hare-Niemeyer | Votes | Ideal claim | Sit after Hare-Niemeyer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPD | 18,488,668 | 246.95 | 247 | 18,438,668 | 246.56 | 247 |

| CDU | 14,167,561 | 189.24 | 189 | 14,167,561 | 189.45 | 189 |

| CSU | 4,315,080 | 57.64 | 58 | 4,315,080 | 57.70 | 58 |

| Alliance 90 / The Greens | 4,110,355 | 54.90 | 55 | 4,110,355 | 54.96 | 55 |

| FDP | 3,538,815 | 47.27 | 47 | 3,538,815 | 47.32 | 47 |

| total (only Bundestag parties) | 44.620.479 | 596 | 596 | 44,570,479 | 596 | 596 |

This means that the total number of basic mandates for the SPD remains at 247 despite the lower absolute number of votes. These 247 seats are now allocated according to the votes of the SPD achieved in the countries:

Calculation of seats for the SPD for the 2002 Bundestag election

| Real voting relationships | 50,000 SPD votes less in Brandenburg | |||||

| Votes for SPD | Ideal claim | Sit after Hare-Niemeyer | Votes | Ideal claim | Sit after Hare-Niemeyer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | 1,989,524 | 26.58 | 27 | 1,989,524 | 26.65 | 27 |

| Bavaria | 1,922,551 | 25.68 | 26th | 1,922,551 | 25.75 | 26th |

| Berlin | 685.170 | 9.15 | 9 | 685.170 | 9.18 | 9 |

| Brandenburg | 707.871 | 9.46 | 10 | 657.871 | 8.81 | 9 (−1) |

| Bremen | 183,368 | 2.45 | 2 | 183,368 | 2.46 | 3 (+1) |

| Hamburg | 404.738 | 5.41 | 5 | 404.738 | 5.42 | 5 |

| Hesse | 1,355,496 | 18.11 | 18th | 1,355,496 | 18.16 | 18th |

| Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania | 405.415 | 5.42 | 5 | 405.415 | 5.43 | 5 |

| Lower Saxony | 2,318,625 | 30.98 | 31 | 2,318,625 | 31.06 | 31 |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 4,499,388 | 60.11 | 60 | 4,499,388 | 60.27 | 60 |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 918.736 | 12.27 | 12 | 918.736 | 12.31 | 12 |

| Saarland | 295,521 | 3.95 | 4th | 295,521 | 3.96 | 4th |

| Saxony | 861.685 | 11.51 | 12 | 861.685 | 11.54 | 12 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 618.016 | 8.26 | 8th | 618.016 | 8.28 | 8th |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 743.838 | 9.94 | 10 | 743.838 | 9.96 | 10 |

| Thuringia | 578.726 | 7.73 | 8th | 578.726 | 7.75 | 8th |

| total (only SPD) | 18,488,668 | 247 | 247 | 18,438,668 | 247 | 247 |

Although a total of 247 seats are retained for the SPD, the 50,000 fewer votes in Brandenburg mean that the 10th Brandenburg mandate will be shifted to Bremen. This is not a problem in itself.

Overview of the overhang mandates (ÜM)

| Real voting relationships | 50,000 SPD votes less in Brandenburg | |||||

| State list seats SPD | Direct mandates SPD | Seats result | State list seats SPD | Direct mandates SPD | Seats result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baden-Württemberg | 27 | 7th | 27 | 27 | 7th | 27 |

| Bavaria | 26th | 1 | 26th | 26th | 1 | 26th |

| Berlin | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Brandenburg | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 (1 ÜM) |

| Bremen | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Hamburg | 5 | 6th | 6 (1 ÜM) | 5 | 6th | 6 (1 ÜM) |

| Hesse | 18th | 17th | 18th | 18th | 17th | 18th |

| Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Lower Saxony | 31 | 25th | 31 | 31 | 25th | 31 |

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 60 | 45 | 60 | 60 | 45 | 60 |

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 12 | 7th | 12 | 12 | 7th | 12 |

| Saarland | 4th | 4th | 4th | 4th | 4th | 4th |

| Saxony | 12 | 4th | 12 | 12 | 4th | 12 |

| Saxony-Anhalt | 8th | 10 | 10 (2 ÜM) | 8th | 10 | 10 (2 ÜM) |

| Schleswig-Holstein | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Thuringia | 8th | 9 | 9 (1 ÜM) | 8th | 9 | 9 (1 ÜM) |

| total (only SPD) | 247 | 171 | 251 (4 ÜM) | 247 | 171 | 252 (5 ÜM) |

Only through the fact that the Brandenburg SPD has won ten direct mandates (and thus one more mandate than it is now entitled to according to the number of second votes) does an overhang mandate arise, while at the same time an additional list mandate has arisen in Bremen. This combination brings the SPD 252 seats in the Bundestag instead of just 251.

The SPD would also have one more mandate if the Brandenburg SPD had only received 549 fewer votes. Then the SPD in Brandenburg would have a seat share of 9.4491 and in Bremen 2.4497, ie in Brandenburg 9 seats (plus 1 overhang seat) - previously 10, there share 9.46 - and in Bremen 3 - previously 2, since share of 2.45. It can therefore happen that a relatively small number of “too many” votes costs a mandate.

A similar example is if the SPD in Berlin would have received 55,000 fewer second votes. Here it was not even completely ruled out that this could have happened during an election test. Several complaints about the electoral review aimed to have second votes deleted from voters in constituencies 86 and 87 (Berlin PDS constituencies). As part of the process, the votes in Berlin were re-counted at the beginning of 2005. However, the count showed that not enough SPD votes could be withdrawn in order to win the SPD a mandate.

Election of the German Bundestag 2005

There were also overhang seats and negative voting weights for the 2005 Bundestag election . This was particularly explosive due to a by-election in the Bundestag constituency of Dresden I on October 2, 2005 in the Free State of Saxony, where another overhang mandate (of a total of four in Saxony) was created.

It is noteworthy that the by-election in an electoral district of a federal state relevant to the overhang could be observed in isolation, the effect on the state of Saxony and the distribution of seats, so to speak under laboratory conditions: In Dresden the CDU "was not allowed" to win more than 41,226 second votes, otherwise you would be one of the overhang mandates has been lost because Saxony would then have received a proportional mandate more at the expense of North Rhine-Westphalia.

In this context, it is also critically assessed that the special nature of the by-election situation made it possible to specifically advertise the non-casting of second votes. In the run-up to the Dresden by-election, this culminated in a joint poster campaign by the CDU and FDP, in which both parties expressly demanded first votes for the CDU and second votes for the FDP. From this it can be seen that the predictability of negative voting weights in connection with a by-election raises even more extensive problems with regard to the equal treatment of all voters and parties than it already does with an election on election day.

In the election in the constituency of Dresden I, a massive split of votes was observed. The CDU managed to stay below the critical second vote mark, which allowed them to retain the mandate from the preliminary allocation of seats.

In total, around 6.5 million votes and 27 seats in the Bundestag were affected by the negative voting weight in the 2005 Bundestag election.

See also

literature

- BVerfGE 95, 335 - Überhangmandate II. Judgment of April 10, 1997 (abstract norm review at the request of the State of Lower Saxony 1995/96).

- BVerfGE 121, 266 - Land lists. Judgment of July 3, 2008.

- Joachim Behnke: About overhang mandates and legal loopholes . In: From Politics and Contemporary History (APuZ). Supplement to the magazine “Das Parlament”. Bonn 52.2003, p. 21. ISSN 0479-611X

- Dirk Ehlers, Marc Lechleitner: The constitutionality of overhang mandates . In: Legal journal. Mohr, Tuebingen 1997, 15/16, 761-764. ISSN 0173-475X

- Martin Fehndrich: Paradoxes of the Bundestag election system. In: Spectrum of Science . Spektrum, Heidelberg 1999,2, 70-73. ISSN 0170-2971

- Friedrich Pukelsheim: Equal success value of voices between claim and reality. in: The public administration (DÖV). W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2004, 10, 405ff (pdf; 146 kB). ISSN 0029-859X

Web links

- Negative voting weight in the 2009 elections , wahlrecht.de

- Journal from politics and contemporary history on German electoral law , Federal Agency for Political Education

- Wrong choice: Why a voice can be harmful , Telepolis

- Negative voting weights and the reform of the Bundestag electoral law , bundestag.de (PDF file; 216 kB)

- Recent history of changes to the federal election law at beck.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c BVerfG, judgment of July 3, 2008, Az. 2 BvC 1/07, BVerfGE 121, 266 - Land lists.

- ^ The resolutions of the Bundestag on September 29 and 30 . In: bundestag.de , accessed on July 25, 2012. The law came into force on December 3, 2011: the nineteenth law amending the federal election law (19th BWahlGÄndG) . In: buzer.de , accessed on July 25, 2012.

- ↑ Der Spiegel: Germany gets new voting rights . dated September 29, 2011, accessed July 25, 2012.

- ↑ BVerfG, press release No. 28/2012 of May 7, 2012.

- ↑ Focus: Negotiating the right to vote. Party squabble over new suffrage , accessed July 25, 2012.

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of July 25, 2012, Az. 2 BvF 3/11, 2 BvR 2670/11, 2 BvE 9/11, full text

- ↑ BVerfG, Press Release No. 58/2012 of July 25, 2012.

- ↑ BVerfG, Press Release No. 58/2012 of July 25, 2012.

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of July 25, 2012, Az. 2 BvF 3/11, full text , paragraph no. 85.

- ↑ Alternatives in the federal election law

- ↑ BT-Drs. 13/5575

- ↑ Focus: Lottery with ballot papers - What mathematicians rarely reveal , 37/2002.

- ↑ BVerfG, judgment of April 10, 1997, Az. 2 BvF 1/9, BVerfGE 95, 335 , 341 and 343 - Überhangmandate II.

- ↑ BVerfGE 95, 335 (390)

- ↑ Handelsblatt: Constitutional lawyers call for consensus from September 5, 2011.

- ↑ Press release ( Memento of the original from October 17, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. of the SPD parliamentary group on October 13, 2011.

- ↑ election opposition WP 86/98 , BT-Drs. 14/1560

- ↑ election opposition WP 65/98 , BT-Drs. 14/1560

- ↑ election opposition WP 214/02 , BT-Drs. 15/1850

- ↑ election protests WP 162/05 , WP 179/05 and WP 181/05 , BT-Drs. 16/3600

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of January 22, 2001, Az. 2 BvC 1/99, full text ; BVerfG, decision of January 22, 2001, Az. 2 BvC 5/99, full text .

- ↑ BVerfG, reporter from June 16, 2000 on Az. 2 BvC 1/99; BVerfG, reporter from June 16, 2000 on Az. 2 BvC 5/99.

- ↑ BVerfG, reporter's letter of December 9, 2004 on Az. 2 BvC 11/04.

- ↑ BVerfG, decision of February 9, 2009, Az. 2 BvC 11/04, full text .

- ↑ Complaints about the election review for the 2005 Bundestag election on wahlrecht.de.

- ↑ a b The two seats for the PDS MPs were previously withdrawn (starting position 598 seats)

- ↑ How many votes were negative in the 2005 Bundestag election? and How many seats was the negative weight of the vote in the 2005 Bundestag election? In: Wahlrecht.de .